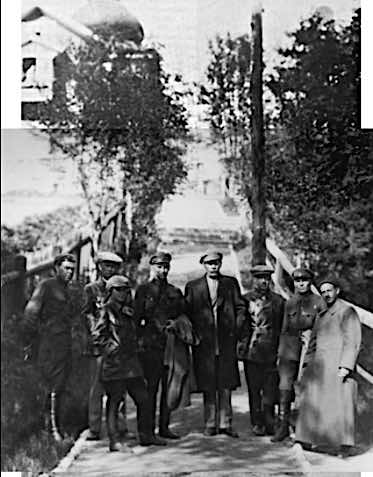

Prisoners of the Solovki camps. Source here.

With an Iron Fist, We Will Lead Humanity to Happiness

—slogan at gate of Solovki prison camp.

Prompted by the troubled memory of abuses under Maoism in China, and the ongoing sensitivity of the topic (cf. my posts on the Nazi camps of Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen), and following my reviews of Orlando Figes’s The whisperers and Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands (for a roundup, see here), I’m gradually, and belatedly, reading up on the Soviet gulag system. A suitable starting point is the Solovki prison camp in the White Sea, prototype for the whole gulag network.

Even during the early years of the camp, some quite frank descriptions of Solovki were published, such as S.A. Malsagov, An island hell (1926) and Raymond Duguet, Un bagne en Russie (1927).

But it was only much later that more thorough accounts would emerge. After the chapter devoted to Solovki in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s seminal The gulag archipelago (1973), Anne Applebaum gives an incisive account of the camp’s history in chapter 2 of Gulag: a history (2003). [1]

The inhospitable Solovetsky islands had been home to a fortified monastery complex since the 15th century, and a remote place of exile under Tsarist rule. After the revolution, the prison camp was constructed from 1923, as the monastery property was confiscated and monks murdered or deported to other camps. The number of prisoners soon grew rapidly. Solovki was itself a network of camps, both on the main island and the yet more lawless outlying islands, becoming a major site for forced labourers constructing the Baltic–White sea canal, all under the brutal direction of the OGPU state security apparatus.

Over the sixteen years of the network’s sorry existence (1923–39), the harsh conditions and the brutal labour regime alone gave rise to endemic, often fatal, disease; but sadism, torture, and executions too were soon routine. As the system was refined, notably under the leadership of Naftaly Aranovich Frenkel—a former prisoner—Solovki became a model for the gruesome system of “corrective” slave labour for profit, such as we see even now in a sinister modern incarnation in Xinjiang. The notion of “re-educating” inmates to create model citizens was always a figleaf.

After a serious incident in 1923, the socialist politicals (who had at first been privileged) were downgraded in status, becoming lower in the hierarchy than common criminals. In its isolation Solovki was virtually impregnable, and only a tiny handful of prisoners somehow managed to escape in 1925, 1928, and 1934 (Gulag: a history, p.358).

Here’s a remarkable silent 79-minute propaganda documentary filmed in 1927–8 (also here; a 5-minute cut, with translated captions, is here):

Cultural life and religion

Like Nazi camps, Solovki had its own concert band, theatrical performances, a library, a printing press, and a Society for Local Lore. [2] But under Frenkel such cultural activities were curtailed.

Remarkably, even religious services were observed in the early years (cf. Famine: Ukraine and China). A former prisoner recalled the “grandiose” Easter of 1926:

Not long before the holiday, the new boss of the division demanded that all who wanted to go to church should present him with a declaration. Almost no one did so at first—people were afraid of the consequences. But just before Easter, a huge number made their declarations. … Along the road to Onufrievskaya church, the cemetery chapel, marched a great procession, people walked in several rows. Of course we didn’t all fit into the chapel. People stood outside, and those who came late couldn’t even hear the service.

Applebaum goes on:

Along with religious holidays, a small handful of the original monks also continued to survive, to the amazement of many prisoners, well into the latter half of the decade. […] The monks were joined, over the years, by dozens more Soviet priests and members of the Church hierarchy, both Orthodox and Catholic, who had opposed the confiscation of Church wealth, or who had violated the “decree on separation of Church and state”. The clergy, somewhat like the socialist politicals, were allowed to live separately, in one particular barrack of the kremlin, and were also allowed to hold services in the small chapel of the former cemetery right up until 1930–31—a luxury forbidden to other prisoners except on special occasions.

Meanwhile, catacomb services were held in secret (for more accounts of the Solovki martyrs, see e.g. here):

As Applebaum relates,

Solzhenitsyn tells the story, repeated in various forms by others, of a group of religious sectarians who were brought to Solovetsky in 1930. They rejected anything that came from the “Anti-Christ”, refusing to handle Soviet passports or money. As punishment, they were sent to a small island on the Solovetsky archipelago, where they were told that they would receive food only if they agreed to sign for it. They refused. Within two months they had all starved to death. The next boat to the island, remembered one eyewitness, “found only corpses which had been picked by the birds”.

Gorky’s visit, and the final days

Maxim Gorky (centre) visiting Solovki, 1929.

In June 1929, to counteract foreign criticism, Maxim Gorky, “the Bolsheviks’ much-lauded and much-celebrated prodigal son”, returned to the USSR for an elaboratedly-choreographed visit that included a three-day visit to Solovki (Gulag: a history, pp.59–62). Though he was not entirely credulous, seeing through part of the official smoke-screen, his report in published form for the international media inevitably put a benign spin on conditions at the camp. As Applebaum observes, “We do not know whether he wrote what he did out of naivety, out of a calculated desire to deceive, or because the censors made him do it”.

Elsewhere too, foreign visitors were easily misled, whether out of enthusiasm for the new social experiment or out of expediency during the struggle against Nazism—such as journalist Walter Duranty for the Ukraine famine, and USA Vice-President Henry Wallace on his 1944 visit to the Kolyma camp in Siberia (Gulag: a history, pp.398–401).

1929 marked “the great turning point”. As Stalin further consolidated his power, the regime becoming ever more draconian, with more systematic persecution of its perceived opponents.

Throughout the Solovki camp’s history countless prisoners were executed, culminating in the Great Terror of 1937–8. As war loomed—with the site lying too near to the border with Finland, and as its main industry of logging was depleted with the deforestation of the area—the camp was closed in 1939, amidst further executions. Meanwhile the gulag system persisted throughout other parts of the USSR right through into the late 1950s, even after the death of Stalin.

The legacy since perestroika

In the 1980s, as memoirs of the period began to be published more widely, intrepid researchers like Yuri Brodsky set about unearthing the dark secrets of Solovki. I’m keen to see Marina Goldovskaya’s 1988 documentary Solovki power (some footage here). But within Russia—even since the collapse of the Soviet Union—the history of the gulags has remained contested (see e.g. here).

As early as 1967, while the Solovetsky monastery was still inactive, a museum had been opened there; by 1989 a new permanent exhibition became the first to commemorate the gulag system. In 1992 the monastery was re-established, and the inscription of the complex on the UNESCO World Heritage list thoroughly downplayed the dark history of the camp.

With official repression of memory continuing to grow in an unholy pact between church and state orthodoxy, by 2015 human rights activists were deploring the removal of all traces of the Solovki camp (see this NYT article from 2015). This article shows how pilgrims from Ukraine have also been obstructed from visiting in recent years.

See also Kolyma tales.

[1] Both works feature in this New Yorker review. Online there are many sites about Solovki, such as here, here, and (an early exposé from 1953) here. For more work by Applebaum, see here, as well as her major study of the famine in Ukraine.

[2] Note the virtual exhibition Beauty in hell: culture in the Gulag (introduced here), with some fine photos—product of the research of Andrea Gullotta (e.g. here; see also this TLS article from 2018).

Pingback: Life behind the Iron Curtain: a roundup | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Lives in Stalin’s Russia | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Bearing witness: If this is a woman | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Bearing witness 2: Sachsenhausen | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Between East and West | Stephen Jones: a blog

This is great–thanks for posting it.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Kazakh famine | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Keeping you guessing | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: The struggle against Mussolini | Stephen Jones: a blog