To further my education on Uyghur culture (series listed here), along with the work of Rachel Harris and others, I’ve been admiring

Musapir is a Uyghur scholar now based in the west, publishing under a pseudonym. Until the clampdown she/he was carrying out research for the Xinjiang Folklore Research Centre (XFRC), led by Uyghur anthropologist Rahile Dawut, working with local communities “to create a digitised knowledge base that could both exist within the state’s ICH framework and honour local cultural protocols and knowledge”.

Rahile Dawut on fieldwork, before she was detained.

The project was “abruptly shut down when Dawut was disappeared in 2017 and the XFRC was abolished as part of the state’s crackdown in Xinjiang”. But there was already a widening gulf between the lives and practices of knowledge-holders and the discourse of “intangible cultural heritage”:

the entanglement of ICH and stability discourses and policies created a highly sensitive and confusing environment within which villagers were constantly trying to understand what was “heritage” and what was illegal practice. […]

Musapir illustrates this with a telling vignette about “Hesen Aka”, a Uyghur elder from one of Kashgar’s vibrant oasis villages, “a holistic practitioner of Uyghur narrative, musical, and healing traditions who has spent his life transmitting Indigenous knowledge and lifeways through prose, poetry, melodies, and ritual practices that have been passed from master to student for generations”:

As a designated regional-level bearer of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) for Uyghur folk songs, Hesen Aka had been assigned to perform “red songs” in villages and at regional events. At that day’s meshrep, he played a traditional two-stringed instrument as he sang There is no New China if there is no Communist Party, The East is Red, and other songs praising the state’s family-planning and poverty-alleviation policies. That night, when it was almost midnight, a woman with a small toddler in her arms knocked softly on his door, affixed to which was a sign in both Chinese and Uyghur, “Glorious Red Singer”. The woman asked Hesen Aka to perform a healing ritual for her son who had a fever and was groaning with pain. “It’s too dangerous”, Hesen Aka said. “If I use the drums, it might draw attention, so it is not good for you or me.” But the woman insisted, pleading very softly, and he finally agreed. He told me to bring some warm water and candles, and then started the ritual, presenting some dried fruit, nuts, and pieces of white cloth as offerings before starting to gently tap upon a drum. He recited some verses in Arabic from the Quran and in another language that I did not recognise, and lastly offered some Uyghur-language munajet [supplications] in the Yasawi style. When he finished, he offered the food and cloth to the woman, telling her that her child had caught the evil eye and she must ensure he rests well. The mother thanked him with tears and quietly left.

Still from Ashiq, the last troubadour.

I’ve always recoiled from the flummery of UNESCO’s “Intangible Cultural Heritage” (ICH) programme, both generally and for Han Chinese traditions. If its effects have been bad enough for the latter, its alienating effects are even more flagrant among ethnic minorities, as Rachel Harris and others have noted. It has been “used to further Chinese state nation-building in ways that do not meaningfully include the grassroots knowledge and holistic practices of Indigenous communities.” In Xinjiang, “top-down ICH policies have been implemented in tandem with increasingly repressive security policies and anti-extremism discourse”.

In a fine section entitled “Lost in translation: ICH as ‘Strange Culture”, Musapir unpacks linguistic incongruities. While the Chinese term fei wuzhi wenhua yichan is cumbersome and alien enough, it becomes even more so in the Uyghur version gheyri maddi medeniyet mirasliri. It was “the language of the state, routinely encountered as official jargon or media-speak that was difficult to relate to”. People were widely aware of the term, often heard on TV, but even its designated representatives seldom used it in conversation (cf. Tibetans).

As Musapir explains, gheyri means “different” or “strange”, and carries a negative connotation; thus the term gheyri maddi was often misunderstood by Uyghur villagers to mean “odd” or “weird” rather than “other-than-material”. Rather as the ponderous Chinese term is abbreviated to feiyi, Uyghurs abbreviate gheyri maddi medeniyet mirasliri to gheyri medeniyet, literally “odd culture” or “strange culture”.

The negative connotation of gheyri in everyday life was compounded by its wide usage in the so-called People’s War on Terror. In this context, gheyri was used in the sense of “strange” or “odd” as a descriptor for practices that had been criminalised as “extremist”. For example, public information broadcasts and posters pasted on billboards on the side of the road that announced the ban on Islamic clothing would instruct people: “It is forbidden to wear strange clothes” (gheyri kiyim keymeslik).

Thus “there was a disconnect between what was officially celebrated as ICH and the heritage that knowledge-holders like Hesen Aka carried and embodied.” Mutatis mutandis, I would apply the following account to ICH projects for the Han Chinese too:

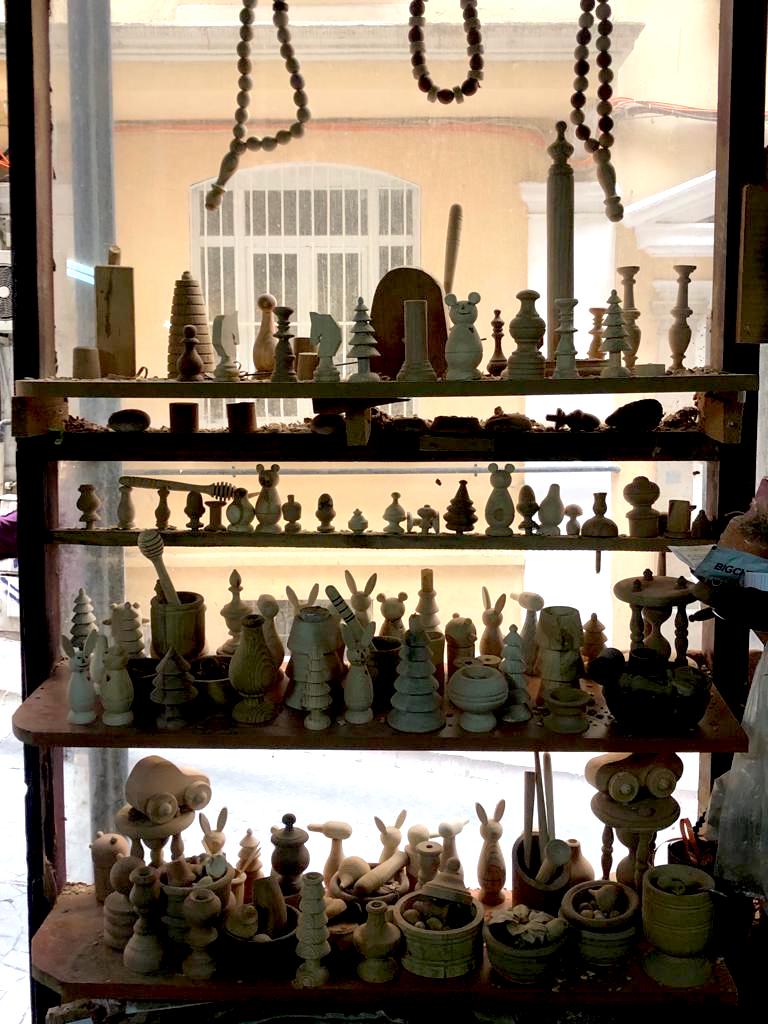

Uyghur practices deemed “outstanding” and inscribed on UNESCO or on national- and provincial-level ICH lists have mostly been reduced to the forms of song, dance or handicrafts. Integral parts of these practices that have a religious connotation, as well as associated traditions such as Sufi rituals, healing ceremonies or ancestral relationship, have been disregarded. As such, ICH plays an important role in the long line of China’s civilising projects, constructing and validating “authentic” versions of Uyghur culture that are stripped of religious or “superstitious” elements.

Musapir goes on:

Supporting the carriers of ICH is an important plank of ICH discourse. However, the knowledge-holders whom I met were clearly struggling for survival. The political pressures they were under were tremendous. With almost no public gatherings being permitted, and even private practice of anything with religious content becoming increasingly risky, many had also lost their only source of income. Some, like Hesen Aka, had joined official song and dance troupes or become “red singers” performing at state-approved meshrep and weddings in villages, at regional events and on state media. Others had become farmers or peddlers, but were struggling to adapt, having been professional storytellers, musicians and (in some cases) healers for their whole lives.

Noting the poverty of the region, he comments:

On one occasion, when I enthusiastically tried to explain the difference between tangible and intangible cultural heritage to a local woman, she retorted: “Tangible? Intangible? Are they edible?” This brought me back to the reality of what was important to them at that very moment, and the vast chasm between their lives and the authorised ICH discourse that had marginalised and alienated them from their embodied Indigenous knowledge.

“Hesen Aka” was detained in 2018-19 and died soon after being released—just one among innumerable victims of the Chinese state’s repressive policies in Xinjiang.

Eliza Carthy with her mother Norma Waterson.

Eliza Carthy with her mother Norma Waterson.

The Turkish music scene in Germany was far from homogeneous. Cem Kaya elicits some excellent comments from characterful musicians. The film opens and ends strikingly with İsmet Topçu, the Hendrix of the bağlama, putting the story in wacky extra-terrestrial context…

The Turkish music scene in Germany was far from homogeneous. Cem Kaya elicits some excellent comments from characterful musicians. The film opens and ends strikingly with İsmet Topçu, the Hendrix of the bağlama, putting the story in wacky extra-terrestrial context…