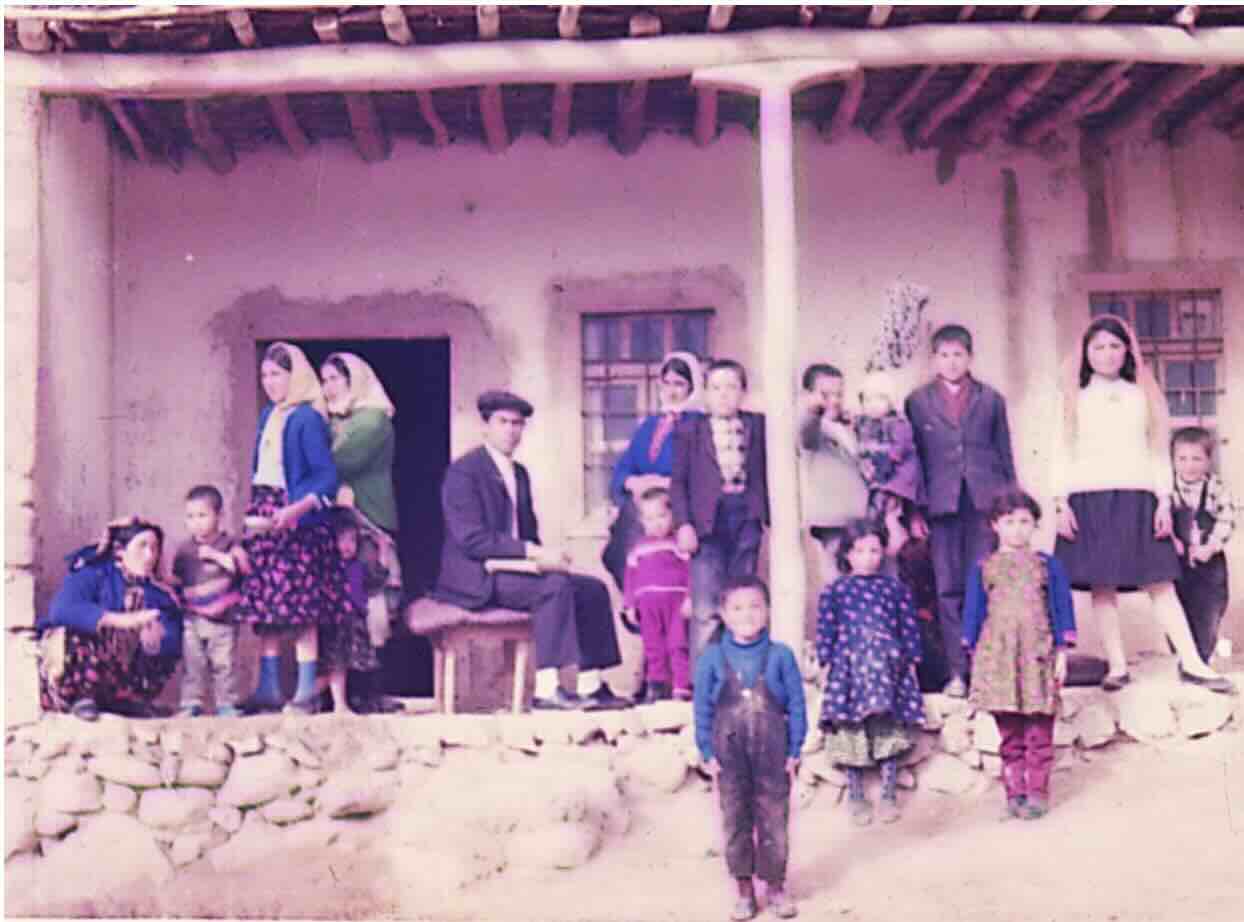

Documenting life in rural Anatolia

As I work my way through the splendid travel catalogue of Eland publishers—such as Three women of Herat, an anthology of Evliya Çelebi (under Musicking in Ottoman Istanbul), and Nigel Barley—I’ve been appreciating

- Carla Grissmann, Dinner of herbs: village life in Turkey in the 1960s.

Her year-long stay in a rural hamlet east of Ankara in the late 1960s was curtailed when she was expelled from the village by tedious visa regulations, so she wrote up the story in frustration soon after returning to New York, but it was only published in 2001.

It’s another outsiders’ view of rural poverty that includes classics such as Christ stopped at Eboli, Let us now praise famous men, and so on (see under Taranta, poverty, and orientalism). Always partial to village studies since my time in Gaoluo, I might not have high hopes for the book as ethnography, since she arrived untrained, learning Turkish as she went along—and yet I concur with Maureen Freely and Paul Bowles that it’s most impressive. Anatolian villagers may not easily relate to a single and childless foreigner:

Through all the months I was at Uzak Köy there was hardly a flicker of curiosity about who I myself was, where I had come from, what I had done before or was thinking of doing next. That I had lived in many places, had worked for a magazine, a newspaper, had taught school meant nothing, except perhaps they could vaguely picture a mud schoolhouse similar to their somewhere in the world. What impressed them was that I was an only child, that I had never known my grandparents, that my mother and father lived separately in different countries and that I had no husband and no children. […] In their experience of life my own life was empty.

But while Grissmann’s natural ability to engage with the villagers recalls Bruce Jackson’s thoughts on rapport, her sojourn was not “doing fieldwork”, but living among people.

“People were in and out of each other’s houses from dawn until bedtime.”

“People were in and out of each other’s houses from dawn until bedtime.”

She immerses herself in her companions’ challenging routine of cooking, cleaning, childbirth and childcare. “There was always music”—songs with saz, lullabies, the village story-teller, a wedding band, all part of social life, and the conviviality of sharing cigarettes. She obliges an old woman who wants her to record a song, weeping as she sang how one of her sons had killed the other “after that quarrel over nothing”.

On topics such as healthcare and education (and indeed, village latrines, or the dependency of the bride in her new home) I’m reminded of the basic concerns of people in rural China.

Although in the village, being able to read and write was of no great usefulness, it was nevertheless acknowledged that some form of non-religious education, at least for the boys, was of value. It gave them an advantage during their military service, and would always be a safeguard against being cheated by the outside world.

Grissmann sees the wider picture:

Turkey had come so far. Much of the population after the First World War had been lost through battle, disease, and starvation. No proper roads existed, only one railway from Istanbul with a few dead-end branches into Anatolia. Malaria and typhoid still broke out. There were no industries, no technicians or skilled workmen, in a country 90% illiterate, with no established government. The heaviest liability, however, of Ataturk’s derelict legacy from the Ottoman Empire was the great mass of benighted peasants, rooted in lethargy, living in remote poverty-stricken villages untouched by the outside world. Ataturk was determined to loosen the hold of Islam on the people, which he believed was the major obstacle to modernization, and to awaken a sense of Turkish national pride. He fought fiercely for the emancipation of women, denouncing the veil, giving them the right to vote and to divorce.

Still, living in the village, such initiatives seemed remote. Confronted by apathy and prejudice, the village schoolteacher had a daunting task:

On every side the teacher faces the wall of tradition, of the older generation. The masses of Turks obediently took off the fez, yet in their vast rural areas they are still bound to their mosque, fetishism, holy men, and superstitions. Women still cover their face. The men believe that women should indeed be veiled, that girls should not go to school, that sports and the radio are the intrigue of the devil. Illness is cured by words from the Koran, written out and folded into a little cloth bag and pinned on a shoulder, or by having the Imam blow on the diseased or ailing parts. The old men sit in rows fingering their beads and say that what their village needs is a new mosque, not a new road. An new mosque, not a new school.

When she offers money from friends in the USA to install basic amenities,

They only partially understood; they could not really visualize the source of this wealth in any tangible, significant way. It was providential, immense, incredible, and yet it remained simple. There was no embarrassment of gratitude.

As to Grissmann’s access to the outside world:

Sometimes a group of children, mute with importance, brought a letter at the crack of dawn, right up to my bed. Most of. these letters had been opened in a friendly way, which I didn’t mind at all. In one fashion or another, everything seemed to arrive, although I never divined any discernable postal system at work or the hand of an actual postman anywhere in the background.

She ponders the process of learning to communicate:

When you are learning a new language I think you inevitably use a great deal of pantomime and mimicry, and develop small speech idiosyncracies, much of which is inevitably expressed through the comic. Beyond the clownish aspect of this can lie true humour, and if you can genuinely share this most subtle and personal sensibility, I think you have won half the battle of human communication. Although the people in the village were extremely reserved in their speech and their manners, and did not seem to express themselves with gesture or emotion, they were an enthusiastic audience and instantly caught the slightest flicker of whimsy and the allusive point of any story. We built up between us a special way of teasing that never ceased to move me, even after endless repetition. Their teasing of me and each other was a warm human thing and seemed to me to be a part of wisdom, an open, guileless generosity of heart.

Dinner of herbs is a work of great empathy.

Carla Grissmann (1928–2011) led a colourful life. Turkey proved to be a stepping-stone from Morocco to her long-term base in Afghanistan. The 2016 Eland edition contains a vivid afterword by her lover John Hopkins.

* * *

This led me on a preliminary foray in search of further ethnographies of Anatolian life. Grissman mentions Mahmut Makal‘s trenchant A village in Anatolia (1954), as well as Yaşar Kemal’s 1955 novel Memed, my hawk. On Makal and later village websites, see this thesis, as well as wiki on the short-lived Village Institutes.

Following Brian Beeley (Rural Turkey: a bibliographic introduction, 1969, and his “Migration and modernisation in rural Turkey”, in Richard Lawless, ed., The Middle Eastern village: changing economic and social relations, 1987), note the work of Paul Stirling (here, with full text of Turkish village, and papers; he also edited the 1993 volume Culture and economy: changes in Turkish villages). This article introduces some other international anthropologists in the field in the late 1960s; here Chris Hann reviews works by Carol Delaney, Julie Marcus, June Starr, and (for urban arabesk) Martin Stokes. I trust there’s much more out there from Turkish ethnographers. My search continues for documentary films on rural Anatolia (cf. Everyday life in a Syrian village).

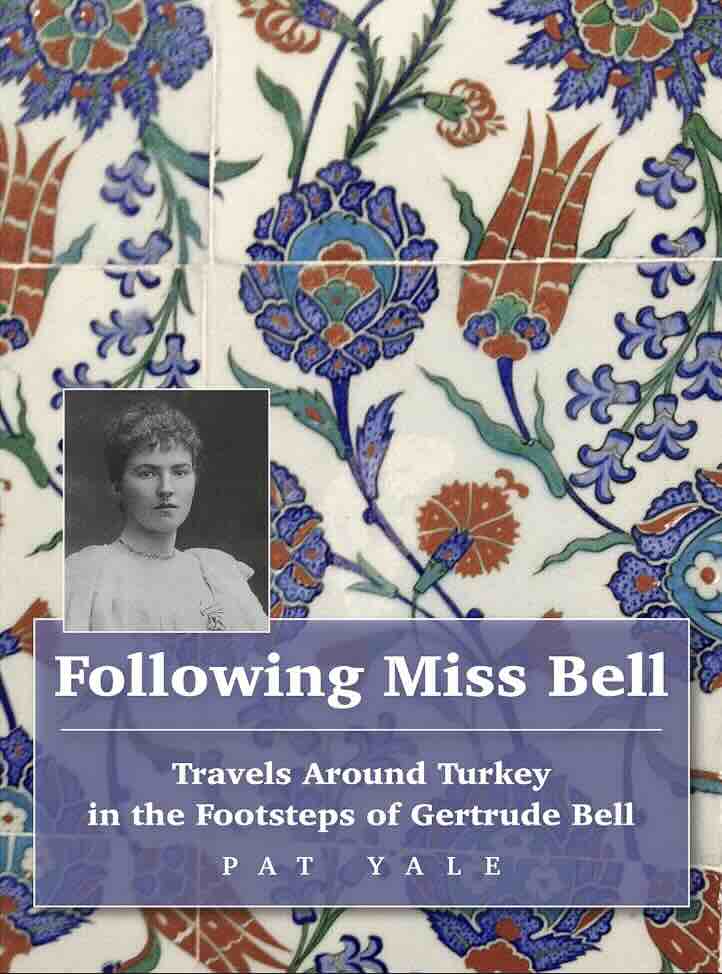

My series on West/Central Asia includes posts on the social life and expressive cultures of rural areas, such as Musicking of the yayla, Bektashi and Alevi ritual, Bartók in Anatolia, Rom, Dom, Lom, A rural woman singer, and Some Kurdish bards. See also Following Miss Bell.

With thanks to Caroline Finkel and Pat Yale,

who are entirely innocent of blame for my rudimentary explorations.

The Shanhua temple during the

The Shanhua temple during the

With Qiao Jianzhong (right) and Huang Xiangpeng, MRI 1989.

With Qiao Jianzhong (right) and Huang Xiangpeng, MRI 1989.

Qiao Jianzhong (left) and Lin Zhongshu (2nd left), 2013,

Qiao Jianzhong (left) and Lin Zhongshu (2nd left), 2013,

With Li Manshan and his Daoist band at the Gallerie, Milan 2012.

With Li Manshan and his Daoist band at the Gallerie, Milan 2012.

Lost Armenian monastery of Surp Asdvadzadzin at Tomarza,

Lost Armenian monastery of Surp Asdvadzadzin at Tomarza,