The Anthology provides another gateway

Like Beijing nearby, the municipality of Tianjin encompasses a large region, much of it still rural. On ritual and its soundscapes there, my previous articles include

So at last I’ve been trying to digest the relevant volumes on instrumental music of the great Anthology of folk music of the Chinese peoples:

- Zhongguo minzu minjian qiyuequ jicheng, Tianjin juan 中国民间器乐曲集成, 天津卷 (2008) (2 vols; 1,475 pages),

which as ever contain substantial material on ritual traditions. To remind you of my introduction to a similar recent survey for Fujian province in southeast China,

Ritual pervades all genres of folk expressive culture: in the Anthology, it is a major theme of the volumes for folk-song, narrative-singing, opera, and dance. In the instrumental music volumes, even genres that lack explicit liturgical content are also invariably performed for ceremonial occasions—but a further reason to consult them is that the specific rubric of “religious music” has been consigned there. I’ve described the flaws of the Anthology project in my

- “Reading between the lines: reflections on the massive Anthology of folk music of the Chinese peoples”, Ethnomusicology 47.3 (2003), pp.287–337.

Apart from the Anthology‘s valuable Monographs for opera and narrative-singing and brief textual introductions to genres, its volumes consist mainly of transcriptions, of limited value without available recordings. Conceptually its classifications are rudimentary, but it opens up a world of local cultures.

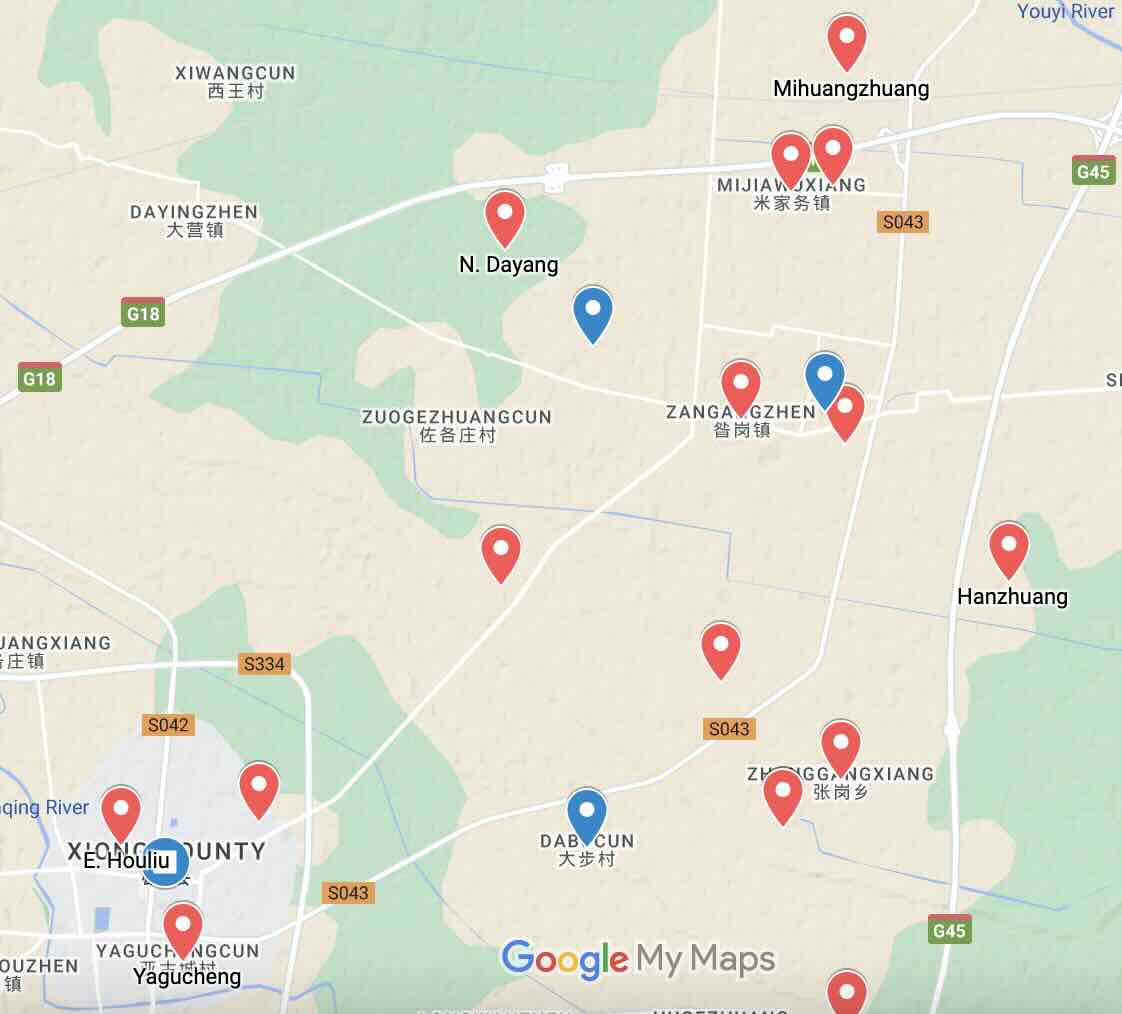

It’s important to grasp the geography of the large regions covered by such surveys (cf. Layers of fieldwork). At the time of compilation the greater Tianjin municipality comprised four suburban areas (east, west, south, north), five counties (Wuqing, Jinghai, Ninghe, Baodi, * Jixian), and three districts (Tanggu, Hangu, Dagang), all of which had distinctive local traditions.

Useful as always are sketches of some leading groups (pp.1327–39) and brief biographies (pp.1340–56), containing promising leads to further ritual associations and sects.

Volume 1 is entirely devoted to “drumming and blowing” (guchui yue 鼓吹乐). Here the rubric of “Songs-for-winds associations” (chuige hui 吹歌会) is misleading (see under Ritual groups of Xushui), compounded by the sub-categories of leading instrument (guanzi, suona, sheng, dizi). While many musicians are versatile on wind instruments, this masks the important distinction between occupational shawm bands and devotional ritual associations led by guanzi. However, there is some valuable historical information bearing on the “classical” style of amateur ritual groups (often known as “music associations” yinyuehui) serving ritual, such as the Tongshanhui 同善会 of Huanghuadian in Wuqing county (p.1336; brief mention here, under “Further leads”). Such groups were to become my main focus (see Menu, under Hebei and Gaoluo).

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

inscribed Xuande reign, 5th year (1429). Besides museums,

folk performing groups preserve important evidence for

the material culture of imperial China (see China’s hidden century).

Shawm bands always occupy a substantial part of the Anthology coverage. Here the summary introduces traditions for all the municipality’s regions, notably in the north around Baodi and Jixian (pp.36–8, 41–2; groups pp.1338–9, biographies p.1343–4, 1355).

The “great music” of Tianjin.

Still under the heading of “drumming and blowing”, a separate rubric introduces the imposing “great music” (dayue 大乐, though here I seem to recall it should be pronounced daiyue) of the Tianjin region. These shawm bands, derived from the Qing court (cf. longchui and Pingtan paizhi in Fujian), were transmitted among the folk through the Republican era until the 1950s, mainly in urban districts but also in the suburbs; but later they became largely obsolete, so the Anthology fieldwork was largely a “salvage” project.

The impressive introduction (pp.599–610) refers to documents from the late Qing, including material on the “imperial assembly” (huanghui 皇会), supplementing that of the dharma-drumming associations), and details the use of the genre at weddings and funerals. Besides recordings made for the Anthology in the 1980s, the appetising transcriptions (pp.611–78) utilise early discs that I’m keen to hear—Pathé (Baidai) from 1908 and the 1920s, Shengli 胜利 from the 1930s. Cultural cadres recorded senior artists in the 1950s and even “in the mid-70s”. By the 1980s, surviving musicians were recorded for the Anthology, and took part in the Boxer movie Shenbian 神鞭 (Holy whip, 1986).

Shifan band, 1930s.

Shifan band, 1930s.

Volume 2 opens with an introduction to the mixed ensemble shifan 十番 (text pp.679–701, transcriptions pp.702–875; further material on the late Qing societies Siru she 四如社 and Jiya she 集雅社 on pp.1327–8). Related to the better-known genres of south China, notably Jiangnan, shifan bands are also found in a few northern regions including Hebei (see my Folk music of China, pp.206–8). In Tianjin, where shifan was part of the thriving Kunqu scene before Liberation, the major figure in documenting the tradition was Liu Chuqing 刘楚青 (1909–99) (pp.1341–2), who used his youthful immersion in the culture to compile a major volume in 1987.

Notable among percussion ensembles (pp.876–1138) are the dharma-drumming associations (fagu hui 法鼓会), which my mentors at the Music Research Institute (MRI) in Beijing were excited to discover in 1986 and 1987 while attending major folk music festivals in Tianjin. These groups commonly subsumed a shengguan melodic ensemble—from the 1986 festival, listen to the MRI’s audio recording of the Pudong “music and dharma-drumming association” in Nanhe township, Xiqing district 西青南河镇普东音乐法鼓会. These events led us to the fieldwork of local scholars—notably Guo Zhongping 郭忠萍, author of the valuable overview in the Anthology (pp.876–97; transcriptions pp.898–1009; see also groups pp.1328–34 and biographies pp.1347, 1349), based on her more detailed early publication Fagu yishu chutan (1991).

This section also introduces the percussion of “entertainment associations” (huahui 花会): “flying cymbals” (feicha 飞镲), stilt-walking (gaoqiao 高跷), dragon lanterns (longdeng 龙灯), and flower drum (huagu 花鼓).

“Religious music”

As always, despite my criticism of the term, this is a substantial category in the Anthology, subsuming some major traditions of Buddhist and Daoist ritual.

Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).

Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).

For major insiders’ accounts by temple clerics Zhang Xiuhua and Li Ciyou before and after the 1949 “Liberation”, see n.1 here, leading to Appendix 1 of my book In search of the folk Daoists of north China and the research of Vincent Goossaert.

Daoist band, Tianjin. Tell us more…

For “Buddhist music” (pp.1141–52) and “Daoist music” (pp.1274–9) the introductions can only serve as a starting point for more sophisticated fieldwork—like the transcriptions (pp.1153–1273 and 1280–1326 respectively). There are slim pickings here—although the section on Daoist temple music provides a remarkable vignette from 1972 (!) on a Pingju opera musician’s visit to Zhang Xiupei 张修培, elderly (former?) abbot of the Niangniang gong temple, to notate his singing for the purposes of “new creation”. This section also introduces Li Zhiyuan 李智远 (1894–1987) of the Lüzu tang and Tianhou gong temples; though laicized after “Liberation”, from 1985 he was able to support the renovation of the Lüzu tang. More promising are the rural areas, where there are always household Daoist bands to explore. The transcriptions end with three items of vocal liturgy from the Western suburbs (pp.1313–26): the popular “Twenty-four Pious Ones” (Ershisi xiao 二十四孝), the “Song of the Skeleton” (cf. the Li family band in north Shanxi), and Yangzhi jingshui 杨枝净水.

The accounts of many folk groups offer glimpses of the sectarian connection. In Yangliuqing township (known for its nianhua papercuts), the Incense Pagoda Old Association (Xiangta laohui 香塔老会, above) of 14th Street (which we visited all too briefly in 1989) had scriptures including Hunyuan Hongyang baodeng 混元弘陽寶燈 and Linfan jing 临凡經. Tracing their transmission back eleven generations to the Wanli era (1572–1620) of the Ming dynasty, they have remained active exceot for the hiatus of the Cultural Revolution. In the western suburbs the Tianxing dharma-drumming association (pp.1331–2) belonged to the Tiandimen sect, and groups in Dagang district (p.33) also derive from Tiandimen and Taishangmen sects.

For all its flaws, the Anthology remains a valuable resource; but as ever, the groups introduced there call for fieldwork from scholars of folk religion as well as musicologists.

* Rural Baodi is known to Beijing musicologists and other intellectuals for its “7th May Cadre Schools” (Wuqi ganxiao 五七干校), wretched sites of exile during the Cultural Revolution—for scholars of the Music Research Institute at Tuanbowa (Jinghai), scroll down here.

Albanian zurna shawms with dauli drums, a

Albanian zurna shawms with dauli drums, a

Ukraine: Mykhailo Tafiychuk on volynka bagpipe of the Hutsuls.

Ukraine: Mykhailo Tafiychuk on volynka bagpipe of the Hutsuls.

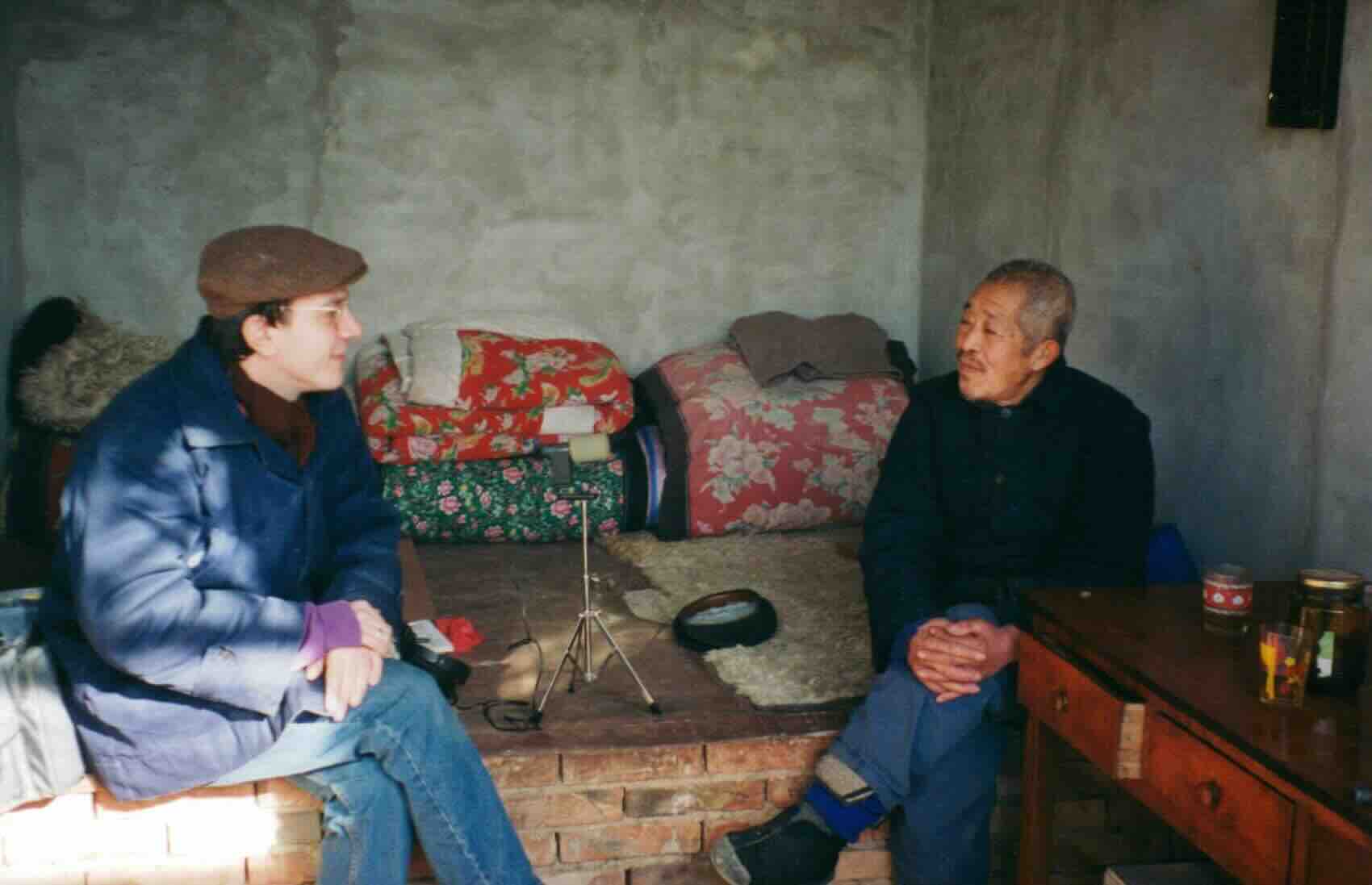

Some association members.

Some association members.