Along with the Silk Roads, that reliably popular buzzword, the Mogao Buddhist cave complex outside the oasis town of Dunhuang occupies a unique position in studies of medieval Central Asia. Having thrived for a millenium from the 4th century CE as a staging post along the trade and pilgrimage route, by the 14th century Dunhuang was a backwater—until its long-hidden treasures were discovered by European explorers in the early 1900s.

Daoist priest Wang Yuanlu, who entrusted many manuscripts to Aurel Stein

and Paul Pelliot from 1907. Source.

The manuscripts are written in a variety of languages, with Chinese predominating.

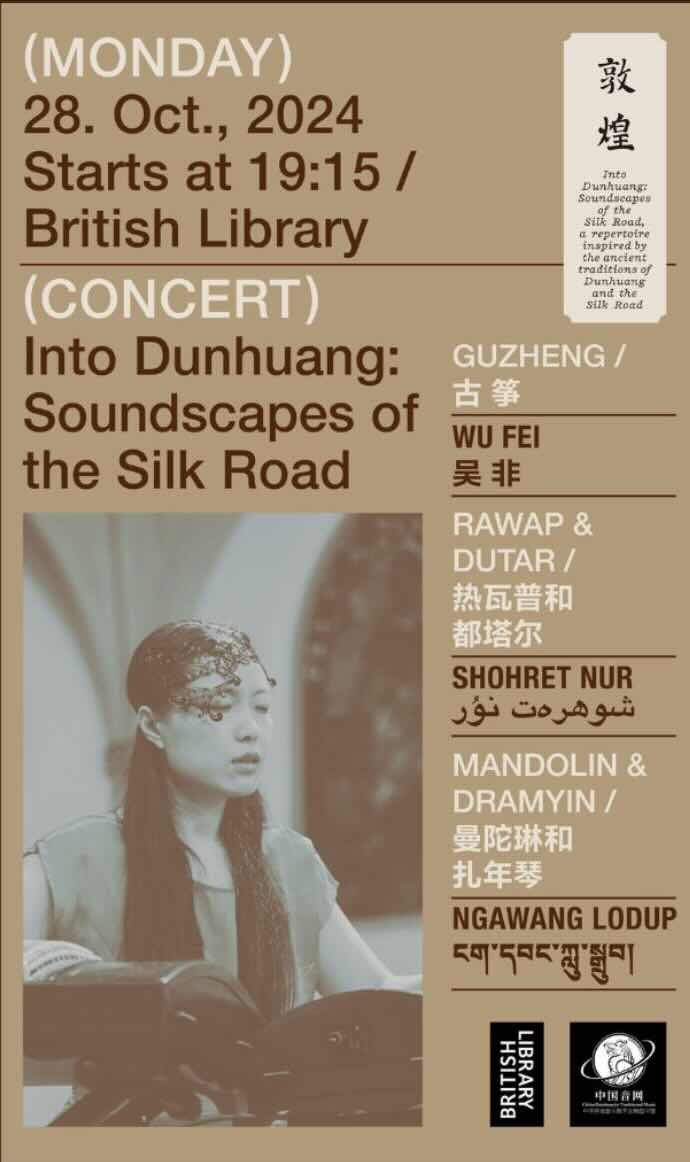

Alongside the British Museum’s current Silk Roads exhibition, the British Library’s International Dunhuang Programme has an impressive collection, sampled in the display “A Silk Road oasis: life in ancient Dunhuang“—with an imaginative soundscape compiled by the industrious Wei Xiaoshi of the China Database for Traditional Music (CDTM). Among a series of related events, this week Wei curated a concert at the BL.

The soundscapes of society are important. Early caves like those of Dunhuang contain a wealth of music and dance iconography, much studied in China. Instruments * depicted there—mainly as part of ensembles—have been reproduced by Chinese scholars. Echoes of the medieval oasis-towns were heard at the court of the Tang capital Chang’an (modern Xi’an), venue for the first world-music boom (see here, and here). Yet early iconography and texts are silent and immobile (alas, the Dunhuang caves haven’t yielded any caches of A/V recordings!). ** And whereas Western performers in the modern tradition of HIP have paid attention to the sound and performance practice of medieval European music, within China attempts at recreation have yielded less palatable results (cf. Tang music), leaving too much at the mercy of the modern imagination—a bandwagon onto which composers and performers climb all too readily without undue concern for authenticity.

The unspoken issue of context deserves pondering. Early murals show idealised representations of the distinct social milieu of celestial musicians (apsara, Chinese feitian 飛天) before the gods; as in Europe, their function in a pious medieval society was far different from that in galleries and museums today. Similarly, modern sonic recreations are performed on the concert stage (cf. Bach)—a venue far removed both from those of the murals and from the diverse human contexts of traditional social musicking in ancient and modern China, whether sacred or secular.

Musical ensemble from Cave 112 (detail), mid-Tang, including zheng zither (front left).

Source.

Doubtless thanks to a limited budget, it was a relief that Wei Xiaoshi adopted the modest rubric “Contemporary echoes of an ancient legacy”, making no pretence of recreating the medieval soundscape, thus avoiding the kitsch spectaculars that are rife in China.

Three accomplished solo performers performed in turn: the Uyghur Shohret Nur on rawap and dutar lutes with busy, percussive pieces from his hometown of Kashgar; the Amdo-Tibetan Ngawang Lodup accompanying his florid singing on mandolin (an instrument widely adopted in modern times by folk musicians around the world) and dramyin lutes—also featuring, to my distress, the notorious “singing bowls” (which “there is no credible historical evidence, whatsoever, of Tibetans ever having used”, in the words of Tenzin Dheden); and the innovative Chinese Wu Fei on zheng zither (whose modern version, FWIW, is remote from that seen in the Dunhuang murals) and vocals. They ended with an improvised trio that I can only describe as strange.

The audience didn’t seem to mind the tenuity of any relation with Dunhuang, ancient or modern. Rather, the concert made a pretext simply to admire the artistry of these fine musicians—from roughly the same part of the world, a millenium after the murals were depicted. Still, were one to present a concert complementing exhibits from the court of Charlemagne (e.g. here), it would hardly seem relevant to present traditional musicians from various parts of France. A millenium is a long time.

It was never going to seem suitable to air the topic of politics, but it was an elephant in the room. As Wu Fei replaced the Uyghur and TIbetan performers on stage with her polished conservatoire-style zheng playing and vocal items, it might just have crossed one’s mind how Han-Chinese rule since 1950 has engulfed Uyghur and Tibetan societies.

Anyway, while research on medieval Dunhuang occupies its own niche, it’s always good to be reminded, however impressionistically, of the variety of living musical traditions throughout the ethnic bazaar of Central Asia, as they have evolved over time (cf. the 2002 Smithsonian festival, or this tasteful concert). For another Silk Roads concert at the BM, click here, and for a symposium, here.

* * *

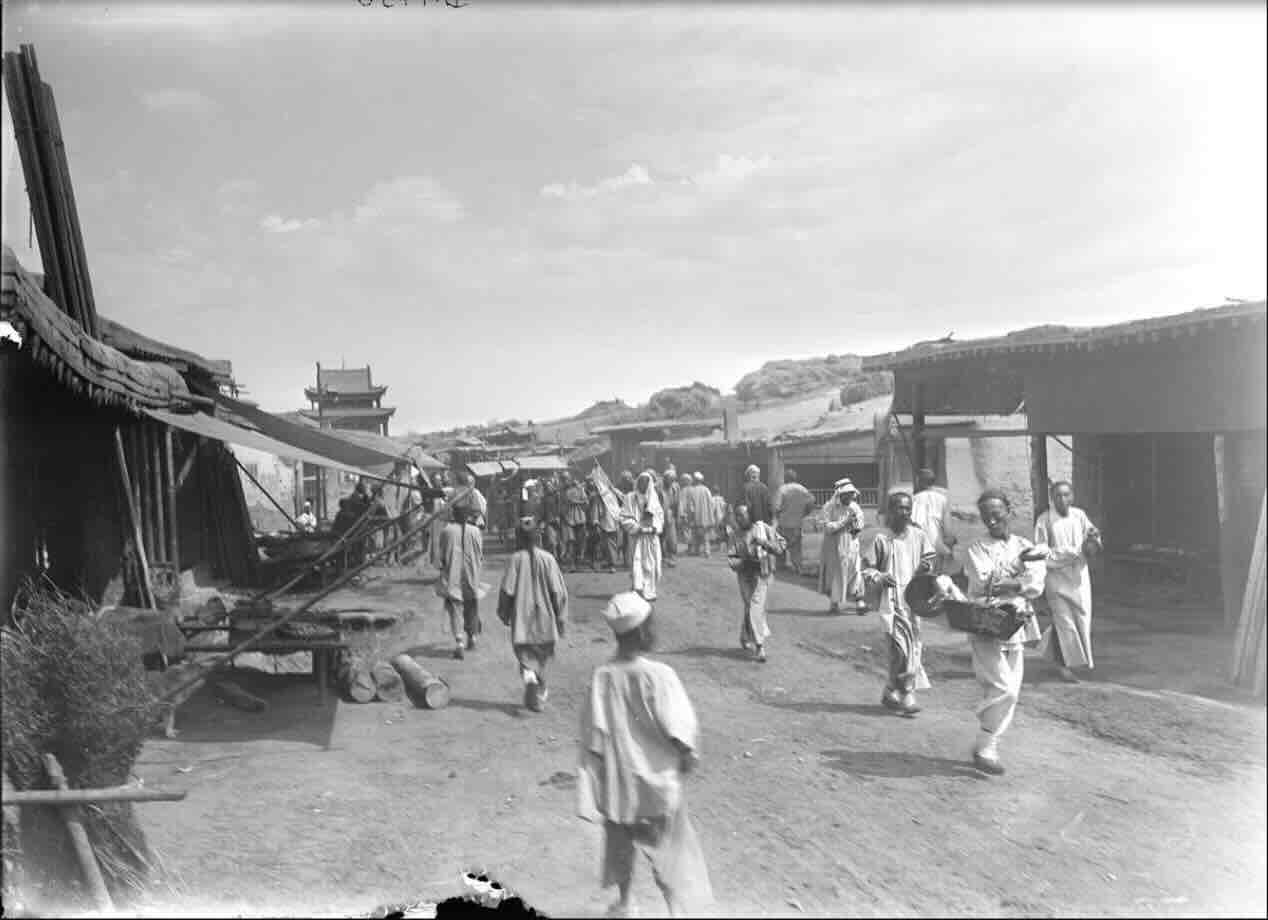

Photo from German Central Asian Expedition, undated (early 20th century):

Photo from German Central Asian Expedition, undated (early 20th century):

shawm and percussion accompanying pilgrims (cf. the Uyghur mazar). Source.

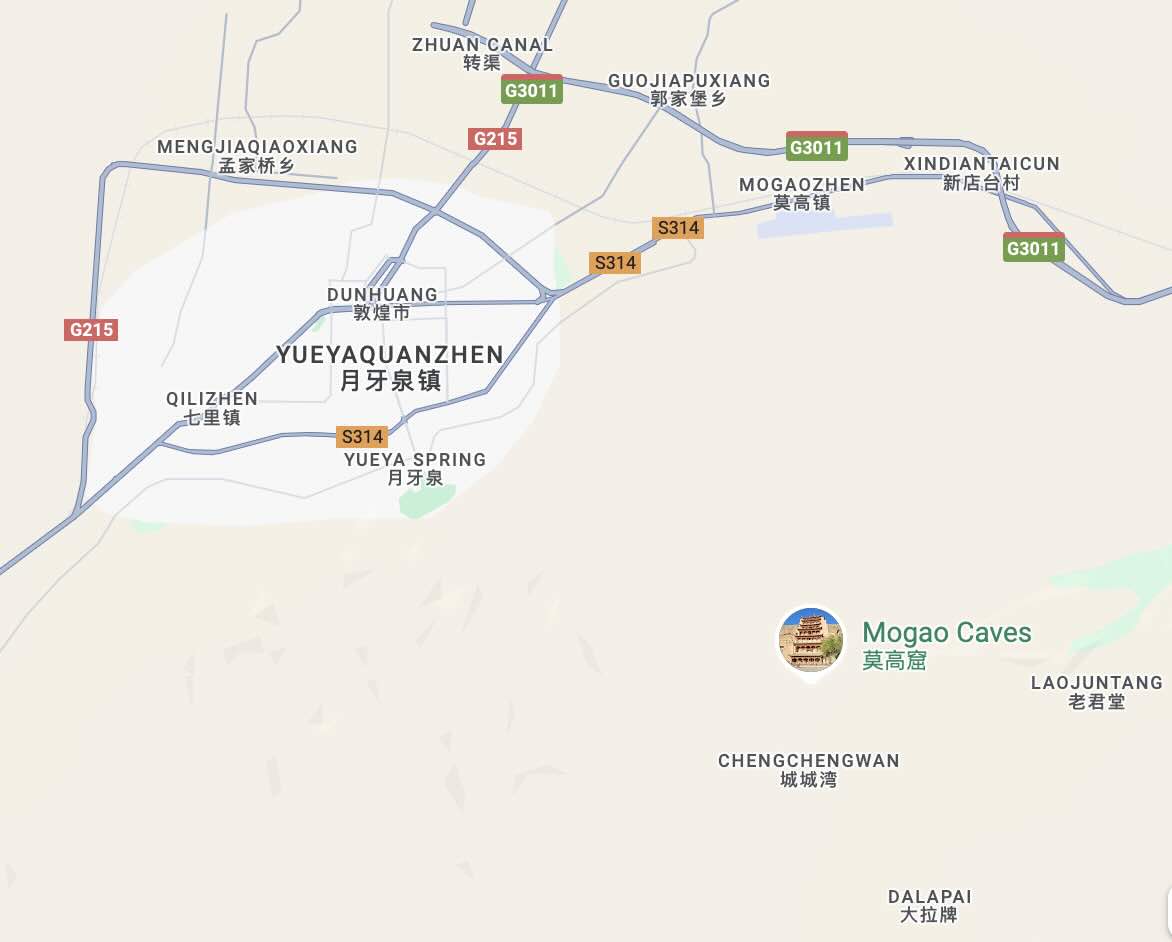

Putting medieval iconography and modern concerts to one side, I muse idly on the potential for documenting folk expressive cultures around Dunhuang since their heyday—from the 14th century down to today. So I look forward to reading the recent compilation Dunhuang minjian yinyue wenhua jicheng 敦煌民间音乐文化集成 [Anthology of folk musical cultures of Dunhuang], comprising three volumes on folk-song, “precious scrolls“, and regional opera.

The Dunhuang region today. Source: Google Maps.

The Dunhuang region today. Source: Google Maps.

Nearby along the Hexi corridor, household Daoist groups perform rituals—for these and other living Han-Chinese traditions in Gansu, click here, and for the cultures of other ethnic groups in the Amdo region, here. For the troubled history of the Dunhuang Academy in the 1960s, note volume 2 of the memoirs of Gao Ertai. For museums and soundscape, see China’s hidden century. Posts on the Tang are rounded up here.

* A personal favourite of mine is the konghou harp, whose rise and fall were similar to that of Dunhuang itself: following the early research of Yuan Quanyou, see e.g. here, here, and even wiki.

Konghou, Cave 285, 6th century (detail).

Konghou, Cave 285, 6th century (detail).

** By a considerable margin, this beats my fantasies of discovering ciné footage of the Li family Daoists presiding over the 1942 Zhouguantun temple fair, or of the first performance of the Matthew Passion.

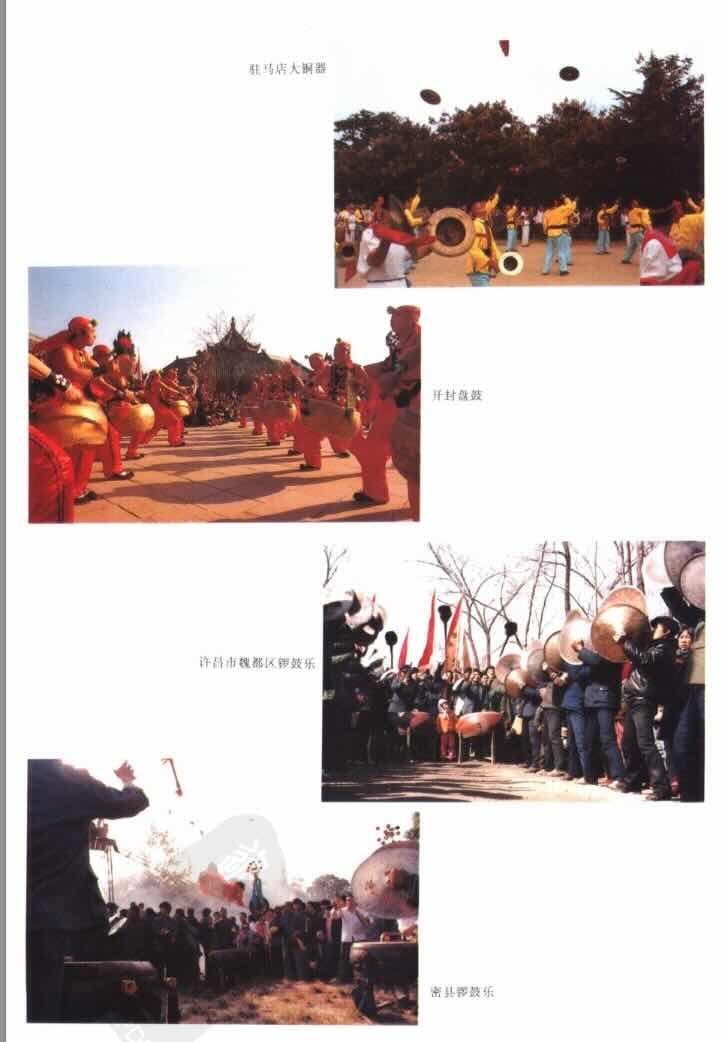

Henan municipalities.

Henan municipalities.

[3]

[3]

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

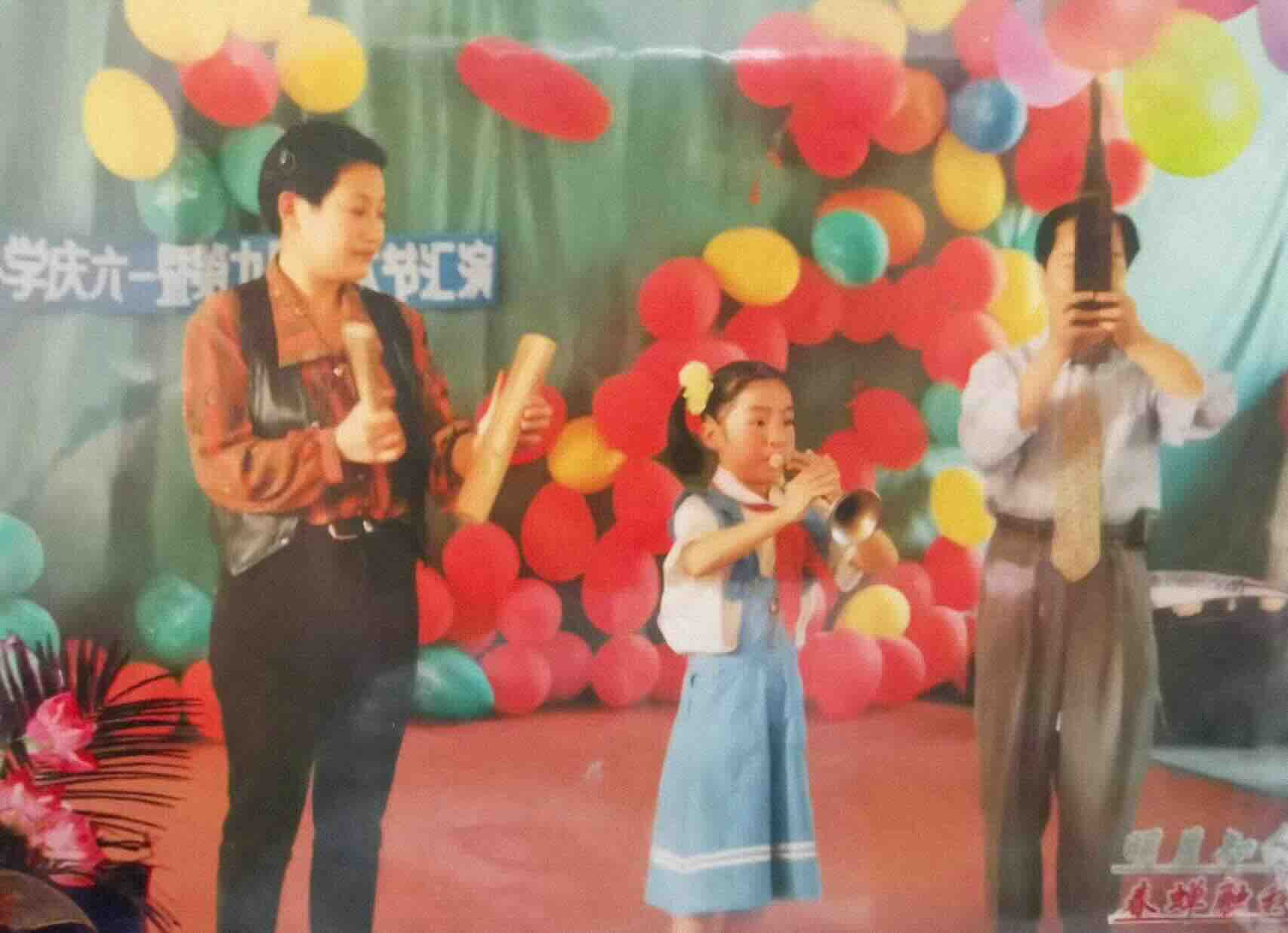

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents.

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents.