by Nicolas Robertson

For links to the complete anagram series, click here.

Prelude—SJ

Since Nick has Ascended to the Great Pinball Table in the Sky, I’ve found two more of his mind-blowing anagram tales. Alceste, which I posted recently, is relatively economical; this one—among stiff competition—is surely his most virtuosic, fantastical (and lengthy) creation. Even the introduction is highly challenging, before we reach the “story” and the final gnomic anagram tale itself. In the absence of Nick’s eagle eye, formatting his text has also been a severe challenge.

Nick’s penchant for tombstones as a medium to connect with the spirits of the past, especially evident here, now seems all the more poignant.

* * *

SALZBURG

Leonore, first version of opera by Beethoven, 1805; shelved and reworked in 1814 as Fidelio.

Fidelio was one act shorter with reordered music; and had a brand new overture. Beethoven commented “almost no musical piece remained the same, and more than half of the opera had been completely reworked”—a description I’ve attempted to reflect.

Staged performances by soloists, Monteverdi Choir and Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, directed by John Eliot Gardiner, including at Salzburg Festival 1996. Archiv recording, issued 1997.

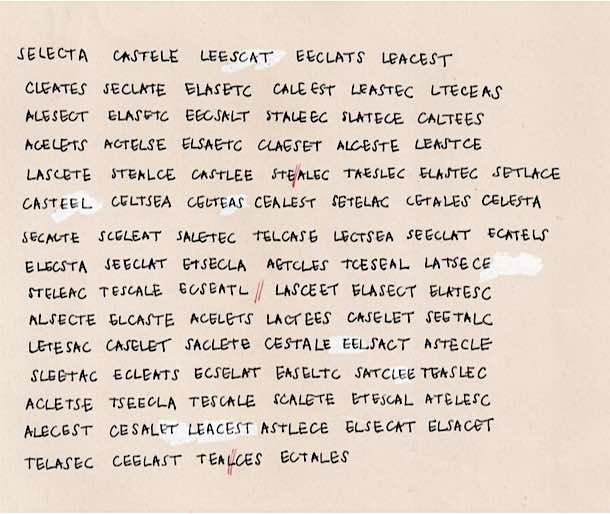

An introduction, the “story”, and lastly the anagrams themselves, of Beethoven’s “Leonore” followed by Beethoven’s “Fidelio”.

[Elements written recently—between 2017 and 2020—principally the “apparatus”, are set in blue to distinguish them from the original 1996 text, augmented in 2012. There are three textual notes, marked in red. Photos were taken later, in 2012 and 2014—one did not have phones with cameras in 1996.]

______________________________________________________________________________

“I hope we English will long maintain our ‘grand talent’ pour le silence”

—Thomas Carlyle, “On Heroes and Hero-Worship”, vi.

Salzburg, summer, Festival and Festung. By day, monsoons and the heavy sun of Mitteleuropa; fading into night, a great still, bulging moon, hanging like a distant punchball, haunting the baroque fountains of a city with too much to remember. Here, one dreams—and sings—of escape: Mozart, from Archbishop Colloredo; Florestan, from prison, and Leonore from half-life to bliss.

Perhaps it was no more than normal for the times, but I could not but be torn by the silent witness of those who escaped far too soon, from a world which had hardly begun to hold out its arms to them. St Sebastian’s Friedhof is a lovely shaded cemetery in a cloister on the other side of the Salzach, and just look what memories call to us from it: of Constanze Weber, Mozart’s wife, yes, and his father Leopold too, but also of the great-grandchildren (I surmise) of stone-cutting master Johann Doppler:

Maria and Anna, born 2 November 1859, died 23 November and 4 December 1860; Otto, 17 February 1868–30 January 1870, and Rudolf, 13 April 1865–5 February 1870 (Johann could have had the melancholy task of engraving their stones, had he not died, aged 45, in 1838). And look, too, Therese Patera, b.1859, d.1861, “geliebtes Kindlein”,

and, without even such ado, “Egbert Almeric Henry-Henry / born Feb 22 1859 / died March 22 1859” (the stone, high up and reticent, is inscribed, without any other words than these, in English).

What was happening in Salzburg in the mid-19th century? Paracelsus, buried in the same St Sebastian’s church in 1541, would have plunged in, reckless of his own health, to fortify the unprotected, even though he well knew that

All, what is, lives.

Nothing is annihilabl,

even Mouldering is transition to new life.

(Tomb of Dominic Oberlechner, d.1821 aged 23, St Peter’s Friedhof, Salzburg—and in English, though you will find a similar text on the same monument in German, French, Latin, and Greek…)

This has, to me, a profound assonance with these words of Claude Lévi-Strauss (as quoted by Douglas Hyde, and printed in the latter’s Guardian obituary, where I read them on the day I wrote this, 22 September 1996):

“Nothing is settled; everything can still be altered. What was done but turned out wrong can be done again. The Golden Age, which blind superstition had placed behind (or ahead of) us is in us.” [1]

[1] “Si les hommes ne sont jamais attaqués qu’à une besogne, qui est de faire une société vivable, les forces qui ont animés nos lointains ancêtres sont aussi présentes en nous. Rien n’est joué; nous pouvons tout reprendre. Ce qui fut fait et manqué peut être refait: «L’âge d’or qu’une aveugle superstition avait placé derrière (ou devant) nous, est en nous.» I’m not sure from where Lévi-Strauss is quoting (Rousseau?); the whole passage in context is cumulatively inspiring. [Tristes Tropiques, 1955, p.471.] The English version above is as used for the epigraph to Alexander Cockburn’s book of essays The Golden Age Is In Us (1995).]

What is this but the quiet request of the Zen master, Hōgen Daidō: “Why not here? Why not now?”, which translated into the high art terms of the western world would find its parallel in the manifesto of Hölderlin quoted by Geoff Boycott later in this story. But, though I happen to be writing these last (preliminary) words in Japan, I find it more appropriate to round the little life of this squib with the Biblical version of that long sleep which was written on the very slab of Johann Doppler (Steinmetzer, der unvergesslicher Gatte)’s descendants; for it’s worth knowing where we came from, even if we don’t know where we’re going (an apothegm which could well apply to this whole anagram lark):

“Der Herr hat sie gegeben, der Herr hat sie genomen,

der Name des Herrn sei gebenedeit!

Wie es dem Herrn gefallenhat, alsoistesgeschehen.” (Job 1.21.)

* * *

There’s a more dynamic, equally important, side to this theme, though:

“Soltai os encarcerados!” (“Let loose the prisoners!”)—when Lídia (die ferne Geliebte) sang these words of Gil Vicente in the tiny eponymous theatre in Cascais in 1969, she was banned, along with the play (“Um Breve Somário da História de Deus”) and the recording made of the songs, by Salazar’s nervous jackboots. But now we’re in the realm of heroes (and heroines, I prefer not to draw the distinction, after all Hero was—is—a girl’s name): the world of Carlyle, of Nietzsche’s Übermensch—not remotely, let us be clear, to be equated with the dummkopf Siegfried whose only quality is that he is “freer than the god”: Nietzsche, and his superman, win their status by thought—as well as, rather engagingly, superior nutrition. (Paracelsus to a T.) *

* [What do I make of the fact that in Salzburg I am staying in the outreach of Himmelreich?—is this not Paracelsus?—whose given names are, Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim. What a place to site an airport… “Ich fühle Luft von anderen Planeten”—so wrote Stefan George, Rosicrucian, Paracelsan poet; another Stefan, Zweig, author of Beware of Pity (thank you to the one who lent me this book those years ago, a lucid notion on her part) eviscerated the Hapsburg heritage, counted the human cost of the dereliction immanent in those huge Tartar plains, and has a -Weg named after him, directly overlooking St Sebastian’s Friedhof, on the Kapuzinerberg where he lived.

The bust, now, to be found at the airport, of Christian Andreas Doppler (can I guess him to be a relative of Johann?—I haven’t been able to do all the necessary research, there must be allowed some holes, to breathe through)—born within metres of Mozart’s Wohnhaus, in 1803, died in Venice fifty years later—is cast however in bronze, not the familiar stone. Furthermore his phenomenal description, known to the English as the “Doppler Effect”, is here called “Doppler-Prinzip”. Cause and effect are not as automatic a sequence as we’d like to think. Cause and effect (I descend from A440 to A430 as the repeating sound waves lengthen) are not as automatic a sequence as we think we’d like… as likeable a sequence as we automatically think…]

The bust, now, to be found at the airport, of Christian Andreas Doppler (can I guess him to be a relative of Johann?—I haven’t been able to do all the necessary research, there must be allowed some holes, to breathe through)—born within metres of Mozart’s Wohnhaus, in 1803, died in Venice fifty years later—is cast however in bronze, not the familiar stone. Furthermore his phenomenal description, known to the English as the “Doppler Effect”, is here called “Doppler-Prinzip”. Cause and effect are not as automatic a sequence as we’d like to think. Cause and effect (I descend from A440 to A430 as the repeating sound waves lengthen) are not as automatic a sequence as we think we’d like… as likeable a sequence as we automatically think…]

I was talking about heroes, heroics. Napoleon was once a hero to Beethoven, until he declared himself Emperor and had to be scratched from the title page of the Eroica—written at the same sort of time as Leonore. It’s maybe not so curious, then, to find echoes of this preoccupation with great men (and women) amongst the jumble of possibilities offered by a shake-up of Beethoven’s Leonore and Beethoven’s Fidelio (to be roughly precise, 230 shake-ups, Fidelio having the tiny edge). Less to be expected, though logical enough if you care to dwell on it, is that one should begin in an atmosphere half-Carlyle (“The Hero can be Poet, Prophet, King, Priest or what you will, according to the kind of world he finds himself born into”—Heroes and Hero-Worship, iii.) and half-Kipling. I append, first, a “translation” (one of finitely many possible) of the jumbly text, and, last, the (re)strained artefact itself.

I owe thanks, indirectly to Nicholas McNair and John Eliot Gardiner (who laid on the raw material), directly to Charles Pott, consistent finder of most of the best individual anagrams (including the title), and essentially to Louis d’Antin van Rooten, author of Mots d’heures, gousses, rames, to Georges Perec, of course, and to those—or the One—responsible for Himmelreich.

Finally, for any who wonder if I shouldn’t indicate the point where “Leonore” anagrams give way to “Fidelio”—I draw the line at that.

____________________________________________________

O BENEVOLENT HEROES

Stalky & Co. M‘Turk, perhaps, is sounding forth about national values, and after teasing poor Beetle pours derision (in his Irish accent) on the Corsican stomach-marcher. Shoving the hapless Beetle forward, he suggests that a music-loving Roman emperor would draw the line at fellow Italian modernists: too subversive, and what’s more unacquainted with Nordic countries.

The same, apparently, could be said for the gifted, unhappy rulers of Ferrara, not least the lovely one who became married to Gesualdo. The only thing to do is concentrate on the job in hand, whittle a snowy-weather vacuum-cleaner which runs on glue. Tony Benn, who’s certainly not to be likened, in his loose diction, to C.S. Lewis’s wonderful talking horse, boy do you stir things up:

“The only pershon to be compawed to Newo ish Beethoven!”

He’s not listened to: there’s more urgent matter. The very vacuum-cleaner’s been nicked: I don’t believe it, I retreat into my shack (the super cabana I staked out myself) and weep.

A multi-national cricket (hockey? football?) competition is a severe rival to track athletics, especially when the star Kenyan’s injured his foot. He goes so far as to contemplate suicide, in Grecian mode, but Helen, dear reposeful one, rules this out, on pain of calling off her Anglo-Saxon lessons. This threat is not esteemed by a couple of more-or-less heavyweight members of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, who call upon a patriarch for help, but it’s left up to the Stage Manager, [2] alert, honourable, to pace around scenting trouble and sorting it out. When I say “pace”, I properly mean “jet”: he checks out Lancashire, the Home Counties, young navvies in south-east Asia, Italy, Africa… where an Afrikaner, salivating with envy, asks if he’s stayed in an Ibis hotel. Of course he has—but not in Egypt, probably only on the outskirts of a French provincial capital.

[2] The Monteverdi stage manager at this time was Noel Mann (see * below).

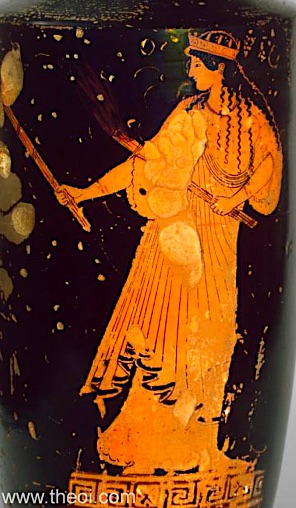

The African connection turns up a more sinister figure: a Ugandan dictator, whose hurly-burly discourse bears nasty connotations of genocide (though pertinently pointing out that Beethoven’s heroine is not in fact Italian), hardly mitigated by attempts at Shakespeare. His interlocutors, perhaps maliciously taunting him with the Othello role he’d have loved, callously ditch him when another mountainous actor drops by. Trans-sexual badinage involving Spartan slavery and a voracious Russian threatens mayhem; but you only need to regard one bordel, one low-cut tee-shirt, to see that eroticism and spiritual affection aren’t remotely separate—they’re the same thing, whether in English or ancient Greek!

* * *

Behold an oboist at rest: except he never is, worrying about his reeds, his obbligato, the last to be heard still practicing in his hotel room before the bus leaves [this passage is inexplicably interspersed with culinary quotidia, as well as uncalled-for speculation on intra-musical relationships]; opining on tempi in what passes for early music nowadays, multiple instrument-making by an eccentric on the South Coast. Lazily he exhorts Sven (who will reappear) to rock on, man (though mistrusting the quality of his sound system, which appears antiquated), calls on my brother to drink to Robert Burt’s exhilarating song to freedom—and, to placate the authorities, ends up paying homage to the author of “La Disparition”, where no “e” is used, proposing a variety of fun lipograms, including “o” and “c”, all of which are turned down, most forcibly by an American law-enforcement agency:

“You can’t trust your alumni, dammit, they can’t spell and they cover up their sloth by using the duplicating machine.”

A Belgian woman, her accent influenced by long residence in the southern hemisphere, says Davie [3] —a friend of hers—gets very upset by not being able to use another vowel, but reckons he’s nothing better than a golfer who can’t complete a round, having played the first 7/18 of the course like an automaton.

The Ryder Cup captain, recalling unexpected speculation on waterbirds, agrees. So much for Divie.

[3] See n.9 and ** in second part, amongst the anagrams.

* * *

Less is known than should be, perhaps, about the Gothic king who was born an Australian woman, descended from the celebrated gin family: who despite his/her facility for dismembering Celtic émigrés gained a reputation as a good man (/woman). Thus do sanguinary impulses and high culture go hand in hand; even the most austere of Japanese art-forms is welcomed.

Yet the threat of plague hangs over his house. Bovine spongiform encephaly has been identified in one of his pet hares—surely it can’t have reached Cornwall? A jumble of thoughts whirls around Otho’s brain, thus:

“Get rid of that rodent Sussexman [4] on TV, he must of done it, I’ll make the old retainer sort him out. Or… was it an insect bite in Nevada? or the early closing times in Rostock? One’s friends’ girlfriends? Disappointment on Merseyside? Devil take it, even the best come to grief. Ooh…” (here a lateral thought carves a wolfish smile across his/her care-worn features) “Game, eh? Well, if not hare, then hoopoe? three poussins? tandoori venison?… oh, praise my Yugoslav aide’s heavenly logic! We dream of Eden, where the classics are easily available in authoritative parallel texts, and great Venetian painters’ (yes, including the one who did St Antony preaching to the fish) works can be enjoyed inalienably, without fear of predatory preemptions by the Getty Museum.” It’s an honourable vision.

[4] Noel Osborne, distinguished Chichester publisher, bass singer and Cathedral volunteer (see n.10, among the anagrams)

* * *

“Is it really you?” Eve gasped.

“It is,” Noel replied, “but do you mind if I call you Joyce? You’ve come to my help at such moments of need, as he did.”

“Then – let me call you Dedalus! You’re so good to cyclostomes out in Dublin Bay, and you single-handedly keep the bar running. I’m only sorry you haven’t persuaded them to do dawn sugar-cups.”

“You’re not telling me – oh, that cupbearer, ye Gods! She’s Greek, you see, she doesn’t seem to understand what I say. But – don’t take it into your own hands – ” Too late. Eve flung her bouquet of roses at Noel’s face, and, missing him, caught Liz, standing isolated apart, snagging her shirt.

“Eve, don’t!” she cried, “these chapel flowers ruin my outfit!” And it’s ruined alright.

“Yes, Eve, it’s all very well…”

Ethel broke in adventitiously, “ ’Ere, I do think Noelene idealises Noel, don’t you?” But Noel, intent on Eve, and spotting that the sun was over the yard-arm, offered her crustaceans; and, giggling, she was his.

* * *

I wish it weren’t the case that traditional Japanese theatre left even distinguished bass singers cold. But, mi love, don’t take it as a slur on west country mores, for there’s more at stake than you think – I speak now für Elise –

______________________* * ______________________

It’s Elise who enters, but she stands for all Beethoven’s unrealisable loved ones, poetesses, countesses, nephews, ideals, half-perceived splendours, renunciations… Elise has the dubious advantage of being here, in the flesh; knowing herself to be paradise personified…

Well, she lived dangerously, while he never risked enough. Was the din of the spheres sufficient compensation for his half-hearted amorousness? First, let’s consider the problem of right and wrong. The latter: Satan, yes, and wretched diseases like Aids (it has been suggested that a hot mustard bath might help); Satan’s hand is seen too in the beef crisis—but I resist, I’m determined to keep on eating meat, be it only well-hung vermin.

Ben asked if I didn’t know a thing or two about fish, as a matter of fact. This is mere provocation. I refuse to plump for one side or the other, between the totems of sky and earth, land and water; I prefer like Jonah to rest my weary head under a grape trellis.

There’s always going to be men who’ll interfere with even this harmless pleasure, who’ll shred the arbour rather than let someone else enjoy it—yet still a dove could fly with an olive leaf in its beak, to find resting place on a sedged nest cocooned by bees. And in the course of time, this first testimony of freedom from the vengeful god expanded. The hive’s roof became covered with ornament; people worked at the reclaimed soil, patiently levelling out the acres granted them, they took the fruit of the olive trees and stoned them, in generations to come they drew out the sting from angry films made by their own offspring. These sturdy, self-reliant people, they thought little of Wall Street reports, they’d be happy that their already pregnant daughters show themselves in public, and would contentedly wear galoshes because they make sense. The marsh folk.

Quite a different world was inhabited by E. Nesbit, author of Five children and it. Lewisham was her background, the bricky parapets of bourgeois southeast London, its gardens full of buddleia run to seed, rudely kempt hortensias amidst sandpits of nettles. But she escaped, at least once, to one of the best hotels in Venice, in search of some clarity of mind. “ ‘Keep apart’, I told myself,” (she wrote) “ ‘if not, you’ll go mad. Could I have joined in union with the Irishman? Would my faith bear it?’ ” Then, there was the cost of the abysmal accommodation, serried ranks like cows. And yet – she knew of a phoenix, she knew of a miraculously-transforming Psammead, she knew of many things…

Allow me a reflection on hotels. “Old Faithful’s Guide” says you can eat well in one upmarket continental chain. Pity me! if that’s the case my public school was a sheep’s bedroom. I ran, when I saw that silky red sheen on the veal—a sure sign of putrefaction, cancel that meat INSTANTER. There’s always wholemeal bread. Just watch the film German TV made about the state of cows’ meat!

Some food, I’m glad to say, is not only healthy but also delectable. Amongst such I include Simon Davies’ buckwheat dropscones, piled up with raw onion, sour cream and caviar. Theo tried this recipe on Eve, as a way of persuading her to drop her silly eating restrictions, not least her refusal to contemplate pied de cochon—Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s favourite dish, after all.

But Steven has opinions about French public figures. He accuses the incumbent of unnatural toilet practices, as well as political immaturity –

“Look at your enemy: don’t do what he does!” But falling into the same error, he invokes an early historian of western Christianity, only to discover him to be as flawed as the rest; and with a guttural, choking cry Steven admits that really it’s the romantic Jewish–Teuton poets whom he adores, thus allying himself with the libertine movement and so, according to some, the party of the Enemy.

I don’t think it’s so, fair-headed Steve, but perhaps it’s not your fault in thinking that passion inextricably involves sleeping with people half your age, that that’s where love is; some American states have endorsed this, after all, and so has a British columnist. Adam, though, the first man, has the right to say: “Eve! Self-indulgence running riot! – is your blood boiling? – then feed the dog. Are you obsessed by your circulation?”

“Yah,” cries Steven, catlike in his happy acceptance of the public’s disapprobation, “Ho!” He’s like a teenage pin-up himself now, do you remember the sort of hero-worshipping books one used to read, “The Story Of A Boy”—a boy who certainly went on to public school –

– but there’s dirtier work afoot. A cover-up, no less, disguised by a performance of The Beggar’s Opera, and further prevarications as to the use of Latin in Robinson Crusoe—a conversation with van Gogh’s long-suffering brother reveals a mutual dissatisfaction with Defoe’s meisterwerk. And yet, Theo admits to a devotion to Ben Gunn, the Treasure Island hermit, admits it even to the FBI whose job it is to eradicate any such romanticism –

“Yeah. We know about this ‘passion’ business. It won’t do, it’s the same as sentimentality about cows: sing your sonnets as you will, we say it’s safer to drink powdered milk.”

* * *

“Do you think life is worth living?” Frustrated, somehow, he plugged on. “I mean—can’t you say life is good, and death is, well – ”

I was too tired to follow up this argument, I watched the sports. The wonderful Scandinavian would get my vote every time, but ‘No’ snaps the snake-master, my great- uncle Ionides, 5 I look after his outrigger, am careful about giving him the respect he deserves.

“You wish to placate the Evil One? – OK, but be quiet about it, there are certain Tokyo spin-offs to be taken advantage of, just remember that when a priest says ‘Credo’ you repeat the words loudly and IMMEDIATELY, all right? We don’t want to be involved with sea-food poisoning or Dutch food embargoes.”

By implication: root out the pupil who won’t behave, even if he’s jealously holding onto a pentatonic recorder (which he won’t play), even if he’s got no spots, prefers to spend his pocket money on deodorants –

– but he’s an innocent beside Sven, Sven’s appetite. Why, Sven alone could retake Thebes, yes, I know that seven were required, but what’s one “e” between friends… Here we have (as well as Sven-Olof):

Fido, the Faithful Hound

Eli – who gives Biblical credibility

Seth – similarly, a son of Adam to boot

Fidel – to remind us this is a genuinely revolutionary enterprise

Niobe – because, finally, it’s always the women who suffer, who lose their children and have to continue doing the housework, shot through with arrows as they are –

and a Presidential candidate who proposes himself for this task, alas, which requires seven-times-over godly efforts –

well, good luck, Robert Dole, let’s just hope you were doing what a man’s got to do.

_________________________________________________

A “Did you lose yourself in summer’s heat?

B Slump to slumber in the Lisbon sun?”

A “Well, perhaps you could call it a treat,

B To blow on aeroplanes the fees you’ve won.”

C “But surely – pictured on the glowing screen?”

D “You think one TV payment pays one’s lunch?

C What if Fidelio’s source had only been

D A dream, a joke, a scream (yes, after Munch)?”

E Some German singers merit more applause

F Than is afforded by a hostile trade:

G They’re chosen, do their best, let’s hope their skin

E Is tough enough to weather what their flaws

F Imply, like English colleagues, thus afraid:

G “At least I brake my shakes with wine, not gin.”

[5] Well, he was family, by marriage—and an extraordinary character, game-hunter-turned-snake- protector, in East Africa, whom it would be a shame to forget.

[SJ: I can’t For the Life of Me find the note cue here, but I cant bear to sacrifice the note… Some intrepid reader might like to supply it…]

Another try at this sonnet (and this time, with a more properly Burgessian rhyme scheme, in feeble honour to another hero):

A “Did you lose yourself in summer’s heat,

B Slump to slumber in the Lisbon sun?”

B “Then waste on aeroplanes the pay I’d won?

A It’s doubtful even you’d call this a treat.”

A “But if you’re dining ’mongst the screen’s elite?”

B “Eating your own wallet’s not much fun.”

B “You’re telling me ‘Fidelio’ couldn’t run

A To sponsoring your ‘gourmand appetite’?”

C “I’m German. Speak in English, if you please.”

D “Your skin’s that thin? Go on—Beethoven knew

E That ‘slow of hearing’ doesn’t mean ‘obtuse’.”

E What prejudices blight one’s hope for truce

D ’Tween sheep and goat (and cow!) – your thought’s askew:

C They’re all washed down by wine (there go one’s fees).

_____________________________________________________

I was sitting in front of the TV in the Long Room, with Ray, Fred, Geoff, the late Brian, E.W. and the lads.

“You see?” groaned Ray, “he never gave his all, the wretch. He preferred the theatricals, the palm-slapping and name-dropping, to a decent job of hard work.”

“But if you only go by the satellite image,” I reasoned, “you may stop them getting away with daylight robbery, but you’ll go to the grave without winning the Ashes.”

“That’s just it,” broke in Geoff—the scope of the discussion was widening—“you put the right bloke in the wrong place, like Wagner in Bloom’s, and you’ll soon find something’s a-missing – ”

“You’re the one who’s missed out, thee…” cried Fred…

“Wait—can’t you feel it?” I said, “there’s a C sounding somewhere…”

“It’s that violinist the committee hired for concert intervals,” Geoff told me. “She gets a ridiculous salary, but there you are! At least when there’s a barn dance she’ll get ’em jumping!”

“That reminds me, it’s time for evensong,” intoned John Arlott. “A manuscript Latin hymn in fa, and an anthem by Délibes.”

“Did you know Délibes was a Foreign Office spy?”

“Got a gong for supporting freedom movements, so I heard.”

“I heard that your brother-in-law’s setting of a Robert Graves poem was found in the Indian laundry!” [6]

Shades of Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro! Careful as he was, obsessive even, rigidly counting each bean, keeping fellow Basque gastronomes one short of a quorum while sating them with extra virgin cold pression olive oil…

[6] & * William Godfree’s song cycle Her restless ghost, settings of Robert Graves, includes the poem whose first line is “O Love, be fed with apples while you may”. I mixed this with memories of “dhobi” and the Ravel story—one doesn’t often find two laundry items in one place (not my responsibility—it was the anagrams, guv) (see * below).

“Look, could Beethoven really not hear? ” asked “Jim” Swanton.

“By that stage he wasn’t Beethoven at all, he’d been swapped for a Russian nabob who used deafness as an excuse to write just anything…”

I looked out of the window, watching the afternoon sun slant across the Lords’ turf. At this hour, I reflected, the Grecian mainland was drenched with the deep shades of late afternoon, the last rays of sunlight touching that so-fought-over town with a glance of lavender… And inwardly looking, as I was, there crept over me a shiver of unspeakable joy.

“But he loved Hölderlin, didn’t he?” I heard Geoff saying. “Just hear this – oh Diana, do you mind putting out the silage for the buffalo? – ‘Thus enlightened and unenlightened must finally join hands, mythology must become philosophical for the people to become reasonable, and philosophy must become mythological in order to make the philosophical sensuous. Then eternal unity will reign among us. Never again the contemptuous glance, nor the blind trembling of the people before its wise men and priests. Only then will equal development of all powers, of each and every individual, await us. No power will be suppressed any more.

‘Then general freedom and equality of spirits will reign ! – A higher spirit sent from heaven must found this new religion among us, it will be the last, greatest work of mankind.’ [7]

“Grand, eh? That’ll make ’em sit up in the Yorkshire committee room!”

“Actually,” said Di, breaking the spell that had settled over us with this uncompromising declaration, “the buffalo’d probably have preferred tuna.”

Well, I might prefer honey. What’s that to do with us now? “Give the food to our Scandinavian friend,” I said.

“Do you think I should? Will he hit me if he doesn’t like it?”

“Who are you asking?” Thinking about it, I wasn’t thrilled with this reply, but was exonerated by the Swede himself, who entered spreading his hands and generously crying, “Anything you can find to eat is fine by me!”

Fine? Does he “love” food in the same way one “loves” one’s pets – buffalos, fish, be they what they will – or Beethoven? If there were no “E” in the language suddenly, or in the musical scale, you might be surprised to find you loved it too, had done all along. “Liebend ist es mir gelungen, Dich aus Ketten zu befrei’n.” It’s through love we know which are the chains, the assumptions, we can break apart – and those we accept –

like, knowing you’re tired, and retiring

(believe, once and for all, every ambiguity is deliberate, exact, even the ones I haven’t noticed)

Not just fine, but,

Fin

(It’s th’ end.)

[7] I’m aware this manifesto is attributed also to Schiller; from what (little) I know of both of them, I feel instinctively its sunlit airiness belongs more properly to Hölderlin, as Nicholas McNair’s original programme article describes, though it’s possible Schiller took it up (as who wouldn’t?). I ́m also aware its presence here isn’t strictly generated by the anagrams, but it is by the opera.

O BENEVOLENT HEROES

“Vote Nelson be hero! Even one-horse, Beetle… Nepoleon? Bonee? SHET!” ’E shove Beetle on. “Nero vetoes Nono [8]: rebel he, he nev’r been to Oslo.”

“Nero? Este, love. Bone, hone, bore the solvent sleet hoover” – E. Benn. (O thee, no sloven Bree.) “Nero’s lone Beethoven.” “Hoover? ’E been stolen.”

“E’en Hoover been stolen?” Enter hovel, sob: “No! ” Best hovel ore, e’en one Robertson hoe; eleven elevens bother Rono, sever heel bone too.

“O, see the obol.”

“No, never. Lethe snob? Oo, never.”

“Eh?”

“Verboten. Else no OE,” vetoes Helen, o the serene love.

“Then boo! ”

“No!” – Leon the obese. Rev. ‘Elven’ Oberst: “Ho! Noé!” ’E bother Noel* even so: ’e hover tense, noble, o, ’e rove N. Bootle, E. Sheen, Esher, Bolton even, o, E. Borneo teen shovel, ’e been Vérone, Lesotho…

Boer: “He seen Novotel?” So – Novotel – been here. Thebes rôle even? Noo. E. Rennes hovel.

Obote: “One Serb hotel oven, Eve – ” (best ‘Leonore’: no ‘eh’) “o three-oven Belsen, seventeen-hobo role. To be or no… ”

“E’en shelve Robeson? Loth. Eee…” (Nev.)

“Ben, Nev’s here!” (O’Toole.) “He’s Renée…”

“Novel. Boot even seen Helot boor, even no hetero-lesbo, Ebeneser Leontov.”

“Ho. See one brothel, one vee, Eros, love – both one!” (ἕν..)

[8] I seem to have swapped vowels between adjacent anagrams, as indicated. I’ve left it, for clear reasons, but sorry, it won’t happen again.

* * *

Robson, toe élevé, lone NH oboe Everest: shove oboe, relent, ennerve, hone solo. (“Beet broth,Selene?” “O no, Eve.”)

O, lento ne’er behoves eleven neo-theorbos. Tenor – love Nobes? Hee… R. Holton v. Nobes? Eeee… Svelte horn, oboe, e’en no bore-hole (vet lens), lone Hove nose-beret. Throb on, Sven, olé!

“Eee ! He be no novel stereo, honest. (Role, one ‘beve’?) Even the Rob solo, ‘Nee…’?”

“O no. See throne? Bevel revel behest: no ‘E’, no ‘O’.”

“No ‘see’?”

“Veto ‘ ’hernobel’.”

“NO ‘SEE’??”

“ ’heviot…” FBI led [9] revolt. “ ‘See’! Oh, none be honest élève. Roneo be sloth veneer.”

Boone (Esther Boone, Loeven) : “Divie bleets of no ‘eh’ ** – boo, seventeen-holer, e’en seven-hole robot.”

Seve: “ ’E bet heron, loon.”

Severe.

* * *

Otho ‘le Bon’, né Noelene Booth, sever Slovene Breton, ho! Eesee. “Noh? Bon.”Oleveret, one BS Eleveret, oh no! ’e BSE even North Looe? Evern Lee, OBE, shoots Noel Osborne [10] (he be TV vole, honest): Reno bee, no Slovene beer o’ the Elbe (o sh, Oenone, Trev – e’en Everton lose…). Hob seethe, von Bono leer. Soon Evoe, treble hen, stone-oven-Rehe, loben Evo’s Booléen ether. Eothen, so noble rêve! Loeb, Veronese (no, the ‘eel’ Veronese, both on ‘no veer’ behest).

[9] and ** The two preceding 17-letter anagrams belong to the second, “Fidelio” half. I can’t tell at what stage they became incorporated here, but, here they are. Perhaps the game with “c”, unavailable in either anagram set, was too absorbing to interrupt.

[10] See note 4 above.

** Here, as promised, the line is drawn.

* * *

“O, Noel !”

“O, Eve! Lebensnot hero!”

“Steven Hero, eel boon, lover to one shebeen! No sherbet levée.”

“O no? Hebe never on toes. Lo!”

“Eve, no!” Beth sore, lone: thorn been sleeve, oo.

“No, Eve – no Bethel rose!” Oo, her bonnet sleeve!

“Bon, Eve…”

Ethel: “ ’onor, ’e’s Noelene Booth’s rêve…”

“Eve?… Noon. Lobster?”

“Heee…!”

O. Noh even bore Steele. Severn blot, o honee? O no.

– ENTER SHE, BELOVE *|* D OF BEETHOVEN –

’Lise: “I : the visible Eden.”

Oof, she fêted oblivion: ’e lived ’s if he been too feeble. Doth noise vie his fèble devotion? Define evil: Hob, so, et HIV (défense: boil toe), the Devil! Beef! Soon I even bit vee of solid, foetid vole.

Ben: “Is he noble fish devotee?” I heed not visible foe. Odin/Eve fé shiboleth, footle beside vine.

“Fie! Bleed vine shoot!”

Bon, i.e. the dove flies to solid fen beehive: festoon beehive lid, hoe, bevel finite sod, bone olive, de-fetish bolshie teen video. FT feeble shine, ovoid fen deb, shoe ‘E’.

Tivoli, Vénise: be ’loof, Edith Nesbit – “O folie! He, Dev? I bet he’d love sin – o fé…” Hotel bovine Dis fee, beside.

Novotel: “If he envies food elite…” (H.B. ‘Fidelis’.) “Oh vé! Eton be ovine shed. Flee bit o’ beef, too livid sheen: believe nosh foetid, beef deletion.” Hovis; Holstein beef video.

Theo fed blini. “So, Eve, diet be foolish? Even edible hoof? I…”

Steven:

“He, fool, envies bidet. Behold foe: évite sin.” Fool, he invites Bede – o the evil sin of Bede! – (sob’d, tief ) – “Love Heine!” Evident Soho belief, i.e. be son of the Devil!

O, blond Steve! If thee, oh, if love is teen bed, fondle, Steve, be Ohio – Levin’s Ohio bed fête…

“Eve! Hedonist foible! – Vein seethe? lob Fido blood. Vein fetish?”

“Ee, the boos feel divine,” boo’d feline Steve, “hi!”. Teen idol he,‘Bevis’ of Eton. “Hide files, be vobis ‘Felon Thieve Ode’.”

“ ‘Vobis ’ ?”

“ ‘Thine’. Defoe, el Isle…”

“O, Defoe be v. thin, Theo.”

“I love Ben, Feds, I – ”

“ – in love ?? Shit. Beef ode. I? I beve Nestlé food.”

* * *

He: “Life is ’bove deth, no?” ’E be foiled – oh, invest. “Life is v. bon – deth? O – eee… ”

I behold Eton fives: Sven-Olof, bei thee I’d…

“Veto!” (Ionides – befehl boot, defensive ‘heil’.)

“Soothe Devil – be fine!”

“Sh! I love Edo benefit. Oh, no deist ? (f) BELIEVE! Hob denotes evil, fie! iodine fob het vlees.”

Boot fiendish élève: he’d five silent oboe, e’en he, divest of boil (b.o. – I’ve invested hole). Ee, the libido of Sven. One v. Thebes? Fido, Eli, Seth, Fidel, Niobe – o vé! Seven-folio Thebeid, sevenfold Hebe, Io, it…”

“… it behoves Dole – fine.”

She: “Fed été oblivion?”

He: “O, I’ve fêted Lisbon.”

“The Lisbon video fee?”

“Vision: hotel feed be.”

“So – if Beethoven lied?”

“So ? ’E felt bovine hide.”

“Oh – is Detlef bovine?”

“Ee! – ist vine flood he be!”

* * *

“Oi, Devon, feeble shit! He believe in soft do : ‘Hi five!’ D. Boon, Steele…”

“Heed television, fob thieves, die of Nobel.”

“O, if Beethoven’s deli void ‘E’ – ” (the ‘E’ snob file…)

“I feel tense doh vib…”

“O, bête violin fee, dosh – hoedo’n: visible feet!”

“Be Ovid in F (sheet), Léo Délibes.”

“The FO envoi!” (Ed.: ‘leftish envoi, OBE’.)

“ ‘O love, be fed’ is in the dhobi.”* O, tensile fève! – eleven foodies bit his oil. “Beethoven def?”

“He Leonid B., Soviet effendi.”

(O Thebes, olive-violet be she.)

“O fine. Di, love, feed the bison.”

“ ’E’d fish volonté.” I, bee

“Feed Bo.”

“Is he violent?”

“Isn’t he?”

Bo: “I love feed!”

He love? ’E??

To bed.

Finis.

May–November, 1996

Nicolas Robertson

The bust, now, to be found at the airport, of Christian Andreas Doppler (can I guess him to be a relative of Johann?—I haven’t been able to do all the necessary research, there must be allowed some holes, to breathe through)—born within metres of Mozart’s Wohnhaus, in 1803, died in Venice fifty years later—is cast however in bronze, not the familiar stone. Furthermore his phenomenal description, known to the English as the “Doppler Effect”, is here called “Doppler-Prinzip”. Cause and effect are not as automatic a sequence as we’d like to think. Cause and effect (I descend from A440 to A430 as the repeating sound waves lengthen) are not as automatic a sequence as we think we’d like… as likeable a sequence as we automatically think…]

The bust, now, to be found at the airport, of Christian Andreas Doppler (can I guess him to be a relative of Johann?—I haven’t been able to do all the necessary research, there must be allowed some holes, to breathe through)—born within metres of Mozart’s Wohnhaus, in 1803, died in Venice fifty years later—is cast however in bronze, not the familiar stone. Furthermore his phenomenal description, known to the English as the “Doppler Effect”, is here called “Doppler-Prinzip”. Cause and effect are not as automatic a sequence as we’d like to think. Cause and effect (I descend from A440 to A430 as the repeating sound waves lengthen) are not as automatic a sequence as we think we’d like… as likeable a sequence as we automatically think…]

*

*

The film does justice to Raymond Chandler’s brilliant prose style. Roger Ebert, always a perceptive reviewer, made some

The film does justice to Raymond Chandler’s brilliant prose style. Roger Ebert, always a perceptive reviewer, made some