As with my remarks on punk and so on,

You think I know Fuck Nothing—but I know FUCK ALL!

Or to adapt it to the topic in hand,

You think I know Shag Nothing, but I know CHAGALL!

More genteel would be the old “I Don’t Know Much About Art, But I Know What I Like!” (groan from Myles). So, following Myles, I write this in the spirit of The Plain People of Ireland. As often, I’m seeking clues relevant to my own areas of study, making connections that can easily get buried beneath our individual specialities. Perhaps this post might be entitled Renaissance art for Dummies in the Field of Daoist Ritual Studies—not one of their bestsellers, I suspect.

Sassetta: St Francis giving his cloak to a poor soldier.

I first came across

- Michael Baxandall, Painting and experience in fifteenth-century Italy: a primer in the social history of pictorial style (1st edition 1972)

while browsing Rod Conway Morris’s library in Venice, along with Horatio E. Brown’s splendidly-titled Some Venetian knockers.

It’s my kind of book, full of the practical detail of materials, technical skill, and patronage, as well as exploring changing perceptions. Quite short, and eminently readable, it gains much from having grown out of a series of lectures that he gave. It addresses issues that I hardly find in discussions of Chinese ritual and music (for any period), so I’d like to explore it at a certain length.

Baxandall opens by encapsulating, in plain and elegant language,** issues that, um, scholars of Daoist ritual (of all periods) should absorb:

A 15th-century painting is the deposit of a social relationship.

On one side there was the painter who made the picture, or at least supervised its making. On the other side there was somebody else who asked him to make it, provided funds for him to make it, reckoned on using it in some way or other. Both parties worked within institutions and conventions—commercial, religious, perceptual, in the widest sense social—that were different from ours and influenced the forms of what they together made.

He observes that

The picture trade was a very different thing from that in our own late romantic condition, in which painters paint what they think best and then look round for a buyer.

Exploring the mismatch between our concepts of “public” and “private”, he notes that

Private men’s commissions often had very public roles, often in public places. A more relevant distinction is between commissions controlled by large corporate institutions like the offices of cathedral works and commissions from individual men or small groups of people: collective or communal undertaking on the one hand, personal initiatives on the other. The painter was typically, though not invariably, employed by an individual or small group. […] In this he differed from the sculptor, who often worked for large commercial enterprises. (p.5)

He meshes all this with detailed technical discussion, like the use of ultramarine:

The exotic and dangerous character of ultramarine was a means of accent that we, for whom dark blue is probably no more striking than scarlet or vermilion, are likely to miss. (p.11)

Thus in the Sassetta painting above, the gown St Francis gives away is an ultramarine gown.

The contracts point to a sophistication about blues, a capacity to discriminate between one and another, with which our own culture does not equip us.

Baxandall notes change over the course of the Quattrocento:

While precious pigments become less prominent, a demand for pictorial skill becomes more so. […] It seems that clients were becoming less anxious to flaunt sheer opulence of material.

But he goes on:

It would be futile to account for this sort of development simply within the history of art. The diminishing role of gold in paintings is part of a general movement in western Europe at this time towards a kind of selective inhibition about display, and this show itself in many other kinds of behaviour too. It was just as conspicuous in the client’s clothes, for instance, which were abandoning gilt fabrics and gaudy hues for the restrained black of Burgundy. This was a fashion with elusive moral overtones.

[…]

The general shift away from gilt splendour must have had very complex and discrete sources indeed—a frightening social mobility with its problem of dissociating itself from the flashy new rich; the acute physical shortage of gold in the fifteenth century; a classical distaste for sensuous licence now seeping out from neo-Ciceronian humanism, reinforcing the more accessible sorts of Christian asceticism; in the case of dress, obscure technical reasons for the best quality of Dutch cloth being black anyway; above all, perhaps, the sheer rhythm of fashionable reaction. (pp.14–15)

To show how skill was becoming the natural alternative to precious pigment, and might now be understood as a conspicuous index of consumption, he returns to “the money of painting”—the costing of painting-materials, and frame, as against labour and skill.

You will no longer be surprised to learn that the Quattrocento division of labour between master and disciples (pp.19–23) reminds me of Daoist ritual specialists.

Baxandall goes on to note the differences in patrons’ demands for panel paintings and frescoes. He attempts to address the issue (even for the time of creation) of public response to painting:

The difficulty is that it is at any time eccentric to set down on paper a verbal response to the complex non-verbal stimulations paintings are designed to provide: the very fact of doing so must make a man untypical. (pp.24–5)

Aesthetic terms expressed in words are contingent, varying from age to age, and anyway elusive. Even with the vocabulary of such accounts, discussing that of a Milanese agent, Baxandall notes:

the problem of virile and sweet and air having different nuances for him than for us, but there is also the difficulty that he saw the pictures differently from us.

He goes on to explore different kinds of viewers’ own exercise of skill in appreciating a painting, with their different backgrounds:

… the equipment that the fifteenth-century painter’s public brought to complex visual stimulations like pictures. One is talking not about all fifteenth-century people, but about those whose response to works of art was important to the artist—the patronizing classes, one might say. […] The peasants and the urban poor play a very small part in the Renaissance culture that most interests us now, which may be deplorable but is a fact that must be accepted. […] So a certain profession, for instance, leads a man [sic—SJ] to discriminate particularly effectively in identifiable areas. (p.39)

Whatever [the painter’s] own specialized professional skills, he is himself a member of the society he works for and shares its visual experience and habit. (p.40)

And given that “most 15th-century pictures are religious pictures”, he asks in detail,

What is the religious function of religious pictures?

His answer, in brief, is that they were used “as respectively lucid, vivid and readily accessible stimuli to meditation on the Bible and the lives of Saints.” But he goes on to enquire:

What sort of painting would the religious public for pictures have found lucid, vividly memorable, and emotionally moving?

[…]

The fifteenth-century experience of a painting was not the painting we see now so much as a marriage between the painting and the beholder’s previous visualizing activity on the same matter. (pp.40–45)

Again he makes the crucial point:

15th-century pictorial development happened within fifteenth-century classes of emotional experience.

Alongside colour, he discusses the beholders’ appreciation of gesture and groupings, adducing dance and sacred drama.

It is doubtful if we have the right predispositions to see such refined innuendo at all spontaneously. (p.76)

And apart from their basic level of piety (largely lost to us today), many of the “patronizing classes” would have assessed the work partly through their knowledge of geometry and the harmonic series.

In Part III Baxandall attempts to sketch the “cognitive style” of the time, with the reservation that

A society’s visual practices are, in the nature of things, not all or even mostly represented in verbal records. (p.109)

Finally he reverses his main argument—that “the forms and styles of painting respond to social circumstances” (and so “noting bits of social convention that may sharpen our perception of the pictures”)—by suggesting that “the forms and styles of painting may sharpen our perception of the society” (p.151).

An old painting is the record of visual activity. One has to learn to read it, just as one has to learn to read a text from a different culture, even when one knows, in a limited sense, the language; both language and pictorial representations are conventional activities. […]

In sum,

Social history and art history are continuous, each offering necessary insights into the other.

Such reflections seem more sophisticated than the “autonomous”, timeless approaches still common in both WAM and Daoist ritual. To be fair, we are quite busy trying to document ritual sequences, hereditary titles, and so on—but the Renaissance scholars have just as much nitty-gritty to deal with too.

* * *

Carpaccio: Baptism of the Selenites, c1504–7 (detail). San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice.

(The painting features a shawm band that I’d love to hear! For Venice’s musical contacts with the East, see e.g. here).

Baxandall ends with a caveat:

One will not approach the paintings on the philistine level of the illustrated social history.

I don’t think he quite had in mind

- Alexander Lee, The ugly renaissance: sex, greed, violence and depravity in an age of beauty (2014),

a less technical, more sociological book with a firm political agenda that some may find more appealing than others (cf. this review of Catherine Fletcher, The beauty and the terror: an alternative history of the Italian Renaissance (2020).

Poking around beneath the glamorous surface image of the Renaissance, seemingly “an age of beauty and brilliance populated by men and women of angelic perfection”, he observes:

If the Renaissance is to be understood, it is necessary to acknowledge not just the awe-inspiring idealism of its cultural artefacts but also the realities which its artists endeavoured to conceal or reconfigure.

Lee explores the brutal social universe in which artists were immersed. Like Baxandall, he explores the relationship between artist and his assistants and apprentices:

The relationship was naturally based on work, and hence could often be punctuated by squabbles, or even dismissal. Michelangelo continually had trouble with his assistants, and had to sack several for poor workmanship, laziness, or even—in one particular case—because the lad in question was “a stuck-up little turd”.

Given that patrons were as important as artists in shaping the form and direction of Renaissance art,

Rather than being seduced by the splendor of the works they commissioned, it is essential to uncover the world behind the paintings; a world that was populated not by the perfect mastery of colour and harmony that is usually associated with the Renaissance, but by ambition, greed, rape, and murder.

He shows the often dubious motives of patrons. They often valued a commission “for the contribution it could make to reshaping the image of often extremely disreputable men”. Such works “were intended more to conceal the brutality, corruption, and violence on which power and influence were based than to celebrate the culture and learning of art’s greatest consumers”.

Lee also seriously questions the image of the period as one of “discovery” of the wider world:

In their dealings with Jews, Muslims, black Africans, and the Americas, the people of the Renaissance were not only much less open towards different cultures than has commonly been supposed, but were willing to use fresh experiences and new currents of thought to justify and encourage prejudice, persecution, and exploitation at every level.

I suspect such angles may not go unchallenged, but I find it refreshing. And these unpackings again augment my comments on the “Golden Age nostalgia” of the heritage industry in China.

* * *

China: jue libation vessel, Shang/Zhou dynasty.

Reception history has perhaps become a rather more established feature of visual culture (including the history of art) than for musical culture. The term “visual culture” itself reflects a more mature holistic approach, like that of “soundscape” for ritual music in China, and indeed the whole inclusive brief of ethnomusicology.

As I dip into Marcia Pointon’s History of art; a student’s handbook, she soon observes:

The meanings of the painting will be determined by where, how and by whom it is consumed.

[..]

Art historians are interested not only with objects with but with processes. […They] concern themselves with visual communication whatever its intended audiences or consumers.

[…]

Art historians investigate the origins, the connections between “high” and “low”, and the ways in which imagery such as this contributes to our understanding of a period of historical time, whether in the present or in the far distant past.

On one hand, as with music, we envy earlier viewers/audiences their familiarity with subjects/languages that we can no longer interpret easily, if at all. At the same time we have also lost the shock of the new.

We’re familiar with the idea of restoring old paintings to their original colours—negating their history?—but we can’t perform a similar operation on our eyes and minds. Doubtless there’s a vast scholarly literature on this, but one might be reluctant to remove the patina from Shang bronzes, restoring them to the condition of glossy new Italian kitchenware. For patina, see also Richard Taruskin’s comments on Gardiner’s Schumann.

Just as most people who experienced art in 15th-century “Italy” had access mainly to those works on public display in their particular city, so, long before CDs and youtube, Leipzig dwellers heard little music apart from Bach and the pieces by other composers that he selected, mostly within the Leipzig tradition. Some creators themselves might be so lucky as to travel, gaining a certain experience of other styles. And in both art forms, a majority of such work was contemporary—even the instruments that baroque musicians played were mostly modern.

To try and get to grips with what art and music meant at the time doesn’t make us able to experience it as did the “consumers” of the day—we can’t unsee Monet, TV, or skyscrapers any more than we can unhear Mahler and punk. And I hope our teeth are in a better state.

* * *

I also admire

- Michael Jacobs, Everything is happening: journey into a painting (2015), [1]

on Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656)—with chapters by his friend Ed Vulliamy added after Jacobs’ untimely death. As Vulliamy observes,

In this half-book, beyond a fragment, we have not only a typically Jacobs-esque narrative of his life with Velázquez—one of chance encounters, aperitifs, musings and restless autobiography—but also this manifesto for the liberation of how we look at painting. (p.146)

Jacobs does that thing that people always do in blurbs:

cutting a picaresque swathe…

—and the picaro simile is fitting. Jacobs was constantly deploring the “sunless” world of academia. He documents the shift in art history that was then occurring widely in scholarship:

Many of the younger lecturers and researchers, conscious perhaps of the lingering popular image of their discipline as a precious and elitist pursuit, began adopting what rapidly became the prevailing art-historical methodology—a pseudo-Marxist one. People who might once have become connoisseurs in tweeds reinvented themselves as boiler-suited proselytisers dedicated to exposing in art revealing traces of the social conditions of a period, often resorting in the process to a hermetic prose peppered with terms I had first come across in Foucault, such as “discourses” and “the gaze”. (p.44)

Oh all right then, I’ll go for a hat-trick:

You think I know Fuck Nothing, but I know FOUCAULT!

(Note on pronunciation: whereas I can only hear “You think I know Fuck Nothing, but I know FUCK ALL!” in the caricature-Nazi accent of Karl Böhm, the above bon mot clearly belongs on the foam-specked lips of an angry young Alexei Sayle.)

By contrast with the treatments of Baxendall and Lee (themselves quite different), Jacobs’ approach is based on including “us”, the viewers, as agents in the picture—whatever his reservations, he was inspired by Foucault.

Proust, writing on Rembrandt, had spoken about paintings as being not just beautiful objects but also the thoughts they inspired in their viewers. [Svetlana] Alpers was cited as saying that “looking at a work in a museum and looking at other people looking at a work in a museum is like taking part in the life story of this work and contributing to it.”

Still, Jacobs ploughed his own furrow. As Paul Stirton recalls,

Michael always believed in the wonder of looking. Yes, there may be a profound message in a painting, but Michael didn’t want to dress it up in philosophical trappings. By all means approach a painting in a scholarly manner, but never lose the wonder. (pp.179–80)

In his book about artists’ colonies at the end of the nineteenth century, The good and simple life, he is scathing about how most painters wanting to live that life considered “the downtrodden country folk … as little more than quaint components of the rural scene. Their social conscience was as little stirred by them as by pipe-playing goatherds in the Roman Campagna.” At moments, though he is the antithesis of a “political” art critic, Michael’s writing reads like Walter Benjamin fresh from his Frankfurt School, but with a glass of Sangria in his hand. (p.182)

From both his own experience and Thomas Struth’s photos of the public response to Las Meninas over several days, Jacobs recalls

All the faces of the bored, the transfixed, the distracted, the deeply serious, the adults whose only concern was to get the perfect snap, the school children who were wondering when their ordeal would be over, the others who fooled around or diligently made notes, the few whose lives were being transformed. (pp.69–70)

So (suitably) like Monty Python’s Proust sketch, Jacobs never quite got as far as discussing the painting “itself”—not so much due to his death, as by virtue of his propensity to dwell on personal reminiscences on modern Spanish history and his own relationship with it and the painting.

He remarks wryly on the images of Spain current in his youth, reminding me of images of China, not to mention Away from it all. He recalls a train journey in the early years of Spain’s transition to democracy, when he was reading a book that

gave no hint of Spain’s repressive military regime, but instead referred to the country’s “growing agricultural and industrial prosperity” and to the “happy coexistence of the old and the new”.

The book’s role as a catalyst for my early, life-changing Spanish journeys was due entirely to its black-and-white photos, which neglected this supposedly modern and prosperous country in favour of basket-laden donkeys, adobe-walled farms, palm groves, sun-scorched white alleys and other such images that endowed Spain with a predominantly medieval and African look. Even Madrid, so regularly criticized by past travellers for its brash modernity, was made to seem more exotic and rural than any other western city I had seen. The sole street-scene was one of a large flock of sheep being herded in front of a neo-Baroque, cathedral-like post-office building popularly dubbed “Our Lady of the Post”. (p.60)

He discusses the fortunes of Las Meninas during the civil war, as well as more recent events:

… closed shops wherever you looked, restaurants offering “crisis menus”, daily protests, and graffiti and posters revealing grievances with everyone and everything, from the monarchy, to the banks, to the multinationals, to the European Community, to the politicians who made Spain the country with the the highest number of politicians per capita in Europe. (p.72)

And he describes the painting’s changing frames and settings:

The Sala Velázquez was like a shrine. […] On entering this inner sanctuary, people took off their hats, spoke in low voices, and tiptoed around so as not to destroy the atmosphere of worshipful solemnity. Every so often someone would be observed bursting into tears.

There were of course others visitors who disliked this room’s churchlike theatricality and the sentimentally nationalistic and mindless emotional reactions it inspired. (p.115)

So as it stands, Jacobs’ book is concerned more with reception history than with the society of the time of the creation of Las Meninas (though he explored this elsewhere, and doubtless had voluminous notes on the painting to supplement existing research). Background on the society of Velazquez’s day is provided mainly by Vulliamy’s fine Introduction. Evoking Lee, he notes that Seville, far from “the great Babylon of Spain, map of all nations”,

was also headquarters of the Inquisition. Indeed, the “Golden Age” which followed the unification of Spain in 1492 was accomplished, writes Michael Jacobs, “in a spirit of brutal fanaticism”, with the expulsion or enforced conversion of Andalucia’s many Moors and Jews. This dogmatism and what we would now call “ethnic cleansing” [here Vulliamy writes with traumatic personal experience in Bosnia] had a major and insidious demographic impact on the city, yet Seville remained characterized by “an architecture … of great contrasts”, wrote Michael, “for alongside the Muslim-inspired love of decorative arts richness is an inherently Spanish love of the austere”.

For a similar approach that sets forth from 17th-century Delft to go global, note Timothy Brook’s brilliant book Vermeer’s hat.

* * *

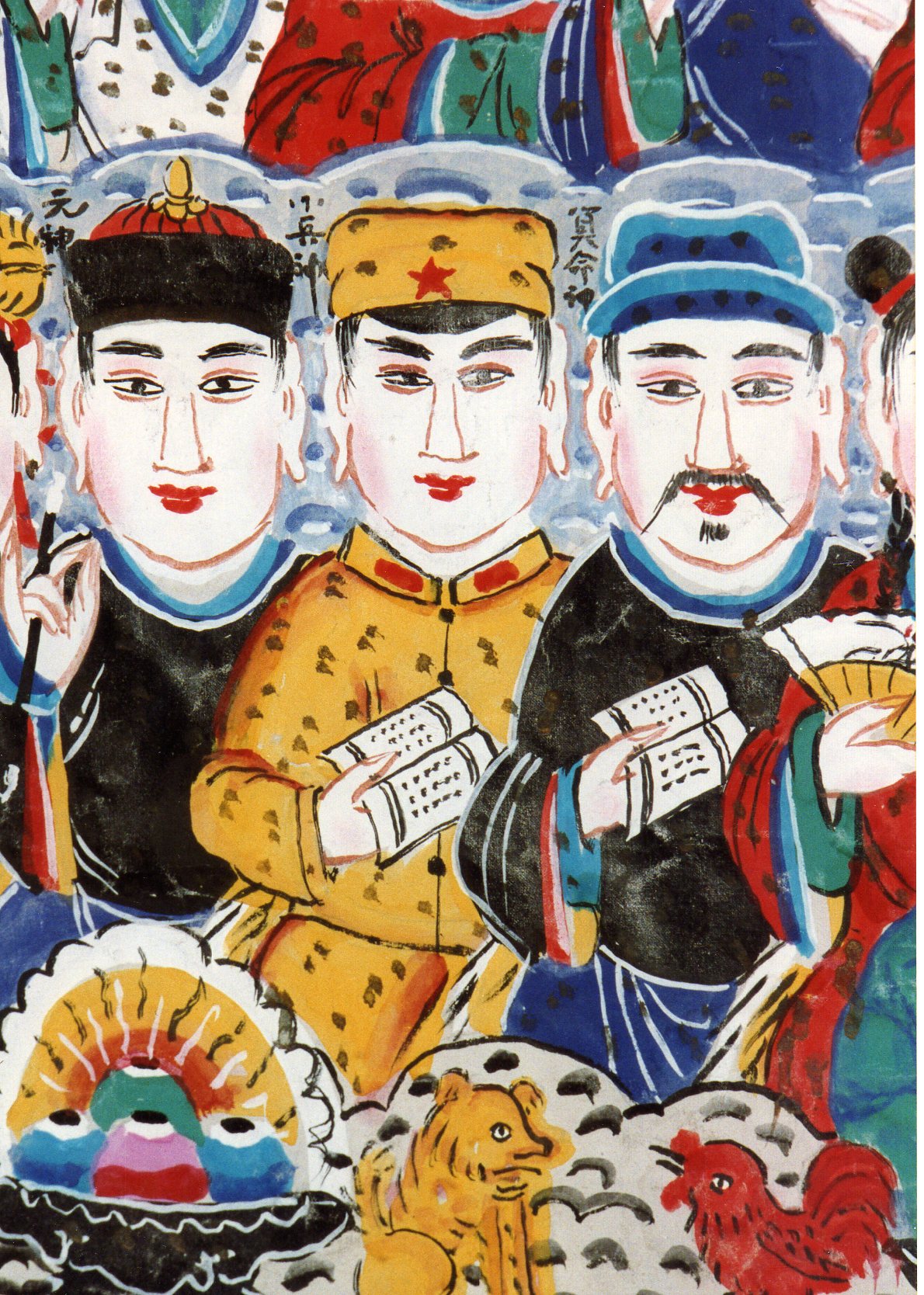

Yama King painting from Ten Kings series, North Gaoluo 1990.

All these books incorporate ethnography and reception history far more than the fusty old reified appreciation of “autonomous” objets d’art. For China,

- Craig Clunas, Art in China (1st edition 1997)

makes a useful, wide-ranging, and thoughtful introduction, exploring themes like genres, techniques, functions, patrons, markets, producers, class, and gender.

For instance, discussing a wooden sculpture of the female deity Guanyin from Shanxi carved c1200 CE, he describes its original multi-coloured decoration:

All this added to the immediacy of the image for worshippers, but it was covered over at some point, probably about 300–400 years later in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), when it was painted gold in imitation of a gilded metal sculpture. Such an aesthetic change must have gone hand in hand with some change in the understanding of what a successful image ought to look like, a change at the level of both popular belief and the attitudes of religious professionals which is as yet hardly understood. (pp.56–7)

Whereas much scholarship remains based on artefacts in museums and galleries, fieldwork reveals a vast further repository of images still used in ritual practice. One thinks of the vast hoard of religious statuettes found in rural Hunan, subject of fine research.

And apart from statues and temple murals, ritual paintings depicting the Ten Kings and the punishments of the underworld—hung out for temple fairs and funerals—suggest comparisons with Christian equivalents in medieval and Renaissance art. And they too must have changed their meanings for audiences over recent centuries. At least, illiterate rural audiences would be affected rather deeply, and modern viewers may be underwhelmed now that they are saturated with horror films and video games. But we learn rather little about this from the scholarship; Daoist culture tends to be reified. Meanwhile, household ritual specialists have continued to perform Ten Kings scriptures for funerals.

It reminds me, challenged as I am in the field of visual culture, that ritual images through the ages also need unpacking—assessing changing meanings there too, including early sources for music iconography.

This has a lot to do with reception history. Such studies of visual culture may feed into our experience of Bach and all kinds of early and folk music. If even scholars of WAM and Renaissance painting feel it germane, then studies of Chinese musical cultures, and of Daoist ritual, shouldn’t lag behind.

* * *

But I’d like to end with some more populist vignettes (“Typical!”) on the meanings of art.

Among the numerous virtues of Alan Bennett is his accessible promotion of painting, found in Untold Stories (pp.453–514) [2]—notably a talk he gave for the National Gallery, with the fine title “Going to the pictures”. These essays are also a passionate plea for culture to remain accessible, a rebuke to mercenary philistine governments.

He recalls an inauspicious early lecture he gave at Oxford on Richard II:

At the conclusion of this less than exciting paper I asked if there were any questions. There was an endless silence until finally one timid undergraduate at the back put up his hand.

“Could you tell me where you bought your shoes?”

We’ve all been there. But his remarks on painting are priceless:

Somewhere in the National Gallery I’d like there to be a notice saying, “You don’t have to like everything”. When you’re appointed a trustee, the director, Neil MacGregor, takes you round on an introductory tour. Mine was at 9am, when I find it hard to look the milkman in the eye, let alone a Titian.

We were passing through the North Wing, I remember, and Neil was about to take me into one of the rooms when I said, “Oh, I don’t like Dutch pictures”, thereby seeming to dismiss Vermeer, De Hooch and indeed Rembrandt. And I saw a look of brief alarm pass over his face as if to say. “Who is this joker we’ve appointed?”

He cites his play A question of attribution, about (Michael Jacobs’ teacher) Anthony Blunt:

“What am I supposed to feel?” asks the policeman about going into the National Gallery.

“What do you feel?” asks Blunt.

“Baffled,” says Chubb, “and also knackered” … this last remark very much from the heart.

[… Blunt] tries to explain that the history of art shouldn’t be seen as simply a progress towards accurate or realistic reprentatation.

“Do we say Giotto isn’t a patch on Michelangelo because his figures are less lifelike?”

“Michelangelo?” says Chubb. “I don’t think his figures are lifelike frankly. The women aren’t. They’re just like men with tits. And the tits look as if they’ve been put on with an ice cream scoop. Has nobody pointed that out?”

“Not quite in those terms.”

In a *** passage AB blends hilarity with insight, evoking Baxandall:

In A question of attribution the Queen is made to have some doubts about paintings of the Annunciation.

“There are quite a lot of them,” says the Queen. “When we visited Florence we were taken round the art gallery there and well … I won’t say Annunciations were two a penny but they were certainly quite thick on the ground. And not all of them very convincing. My husband remarked that one of them looked to him like the messenger arriving from Littlewoods Pools. And that the Virgin was protesting that she had put a cross for no publicity.”

This last remark, though given to the Duke of Edinburgh, was actually another flag of distress, stemming from my unsuccessful attempts to assimilate and remember an article about the various positions of the Virgin’s hand, which are an elaborate semaphore of her feelings, a semaphore instantly understandable to contemporaries but, short of elaborate exposition, lost on us today. It’s a pretty out-of-the-way corner of art history but it leads me on to another question and another worry.

Floundering through some unreadable work on art history I’ve sometimes allowed myself the philistine thought that these elaborate expositions—gestures echoing other gestures, one picture calling up another and all underpinned with classical myth—that surely contemporaries could not have had all this at their fingertips or grasped by instinct what we can only attain by painstaking study and explication, and that this is pictures being given what’s been called “over meaning”. What made me repent, though, was when I started to think about my childhood and going to a different kind of pictures, the cinema.

When I was a boy we went to the pictures at least twice a week as most families did then, regardless of the merits of the film. I must have seen Citizen Kane when it came round for the first time, but with no thought that, apart from it being more boring, this was a different order of picture from George Formby, say, or Will Hay. And going to the pictures like this, unthinkingly, taking what was on offer week in week out was, I can see now, a sort of education, and induction into the subtle and complicated and not always conventional moral scheme that prevailed in the world of the cinema then, and which persisted with very little change until the early sixties.

Unpacking the complex attributes of two stock characters, he concludes:

The 20th-century audience had only to see a stock character on the screen to know instinctively what moral luggage he or she was carrying, the past they had, the future they could expect. And this was after, if one includes the silent films, not more than thirty years of going to the pictures. In the sixteenth century the audience or congregation would have been going to the pictures for 500 years at least, so how much more instinctive and instantaneous would their responses have been, how readily and unthinkingly they would have been able to decode their pictures—just as, as a not very precocious child of eight, I could decode mine.

And while it’s not yet true that the films of the thirties and forties would need decoding for a child of the present day, nevertheless that time may come; the period of settled morality and accepted beliefs which produced such films is as much over now as is the set of beliefs and assumptions that produced an allegory as complicated and difficult, for us at any rate, as Bronzino’s Allegory of Venus and Cupid.

For a similar case, see here.

* * *

Apart from any intrinsic merit this little tour of visual culture may have, for me it also suggests several angles barely explored for Daoist ritual.

OK then, just one last aperçu—this time from Kenneth Clark (thanks, Rod). On the contrast between reified art and social reception, here’s his typically urbane formulation in Civilization:

At some time in the 9th century one could have looked down the Seine and seen the prow of a Viking ship coming up the river. Looked at today in the British Museum, it is a powerful work of art; but to the mother of a family trying to settle down in her little hut, it would have seemed less agreeable.

On behalf of the splendid Craig Clunas, I accept full responsibility for any inanities in this post.

If you all play your cards right, I promise not to do this kind of thing too often. Craig and any other art historians who have managed to read this far might care to exact revenge by writing Specious Flapdoodle [famous 19th-century Baptist pastor—Ed.] about early music or Daoist ritual…

** Not, may I just say, the kind of moronic homespun language used by one maniacal Führer about another: “smart cookie” or “total nut-job”? Roll over Cicero.

[1] Some stimulating reviews may be found here, here, and here.

[2] Online excerpts include http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/i-know-what-i-like-but-im-not-sure-about-art-1620866.html and https://www.lrb.co.uk/v20/n07/alan-bennett/alan-bennett-chooses-four-paintings-for-schools.

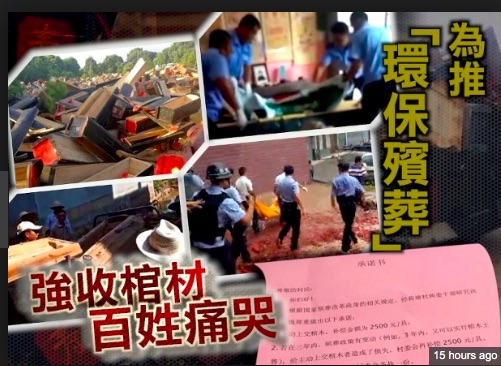

So while there are complex issues at work here, the recent directive illustrates a common befuddled knee-jerk response from local government. If they’re so keen on harking back to Maoist values, they might instead consider a re-education campaign for cadres—it is they who now lead the way in “vulgarity” and

So while there are complex issues at work here, the recent directive illustrates a common befuddled knee-jerk response from local government. If they’re so keen on harking back to Maoist values, they might instead consider a re-education campaign for cadres—it is they who now lead the way in “vulgarity” and