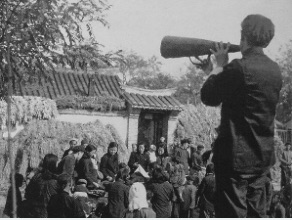

Household Daoists tend to know about performance, not doctrine. I focus on practical knowledge—right down to which cymbal patterns to use as interludes for which hymns, and when to use them, or not. What the Li family don’t know, or do, is things like secret cosmic visualizations.

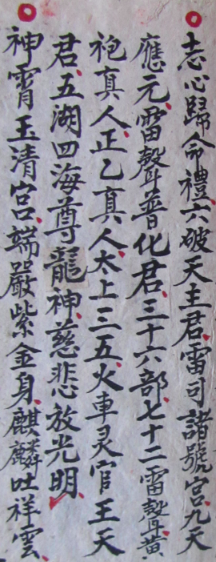

They don’t necessarily know how to write the texts, or if they do so (for me) they may write some characters a bit approximately because they already know how to recite them.

They know nothing of Laozi’s Daode jing, so central to Western images of Daoism. When I quote the pithy, nay gnomic, opening two lines to Li Manshan and his son Li Bin:

道可道非常道 The way you can follow is not the eternal way;

名可名非常名 The name you can name is not the eternal name.

they don’t quite get it, and I have to translate it into colloquial Chinese for them! Hmm…

We have a bit of fun playing with feichang, which in modern Chinese is “very”, rather than the classical “not eternal”. Actually, in their local dialect they don’t use feichang at all, though of course they know it. In Yanggao the usual way of saying “very” is just ke 可, pronounced ka—thus “dao kedao feichang dao” might seem to be “The way is soooo waylike, I mean it’s just amazingly waylike”…

Still, Daoists like Li Manshan will have picked up a broad understanding of the texts they sing every day, even if they have never been taught their “meaning”. They know Laozi not as the author of the Daode jing but as a god.

As I wrestled with translating the Hymn to the Three Treasures (Sanbao zan), used for Opening Scriptures in the morning (Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.262–3, and film from 22.01), Li Manshan explained it to me.

Hymn to the Three Treasures, from Li Qing’s hymn volume, 1980.

The subject of the first verse to the dao, “We bow in homage to the worthy of the dao treasure, Perfected One without Superior” (Jishou guiyi daobaozun, Wushang zhenren) is Laozi himself, so it is he who is the subject of the remainder of the verse: “He descended from the heavenly palace” (xialiao tiangong) refers to Laozi descending from the heavenly palace after beholding the sufferings of the deceased spirit (guanjian wangling shou kuqing)—it’s all about Laozi! So you see, Li Manshan does get the texts…

As for any ritual tradition, where does the “meaning” reside, when texts are unintelligible to their audience? When we translate and explain ritual texts, we are radically altering them as experienced by their audience. True, the performers, the priests, certainly “understand” them, to various degrees, if not in the same way as scholars translating them. I don’t suggest limiting ourselves to the consideration of how people experience rituals, but that should surely be a major part of our studies. Experience lies beyond textual exegesis, consisting largely in sound and vision.

I am reminded of Byron Rogers on an American version of the New Testament (Me: the authorized biography, p.268):

Pilate: “You the King of the Jews?”

“You said it.” said Christ.

There’s another one for the Matthew Passion (cf. Textual scholarship, OMG). “What is truth?”, indeed…

Mercifully, there is no movement to translate the ancient texts of Daoist ritual into colloquial modern Chinese. Of course, for northern Daoist ritual a modern translation wouldn’t make the texts any more intelligible anyway, given the slow tempo and melisma.

Laozi does appear in one of our favourite couplets for the scripture hall (see Recopying ritual manuals, under “The couplet volume”; cf. my book pp.194–5—not easily translated!):

穩如太山盤腿座 Seated in lotus posture firm as Mount Tai,

貫定乾坤李老君 Old Lord Li thoroughly resolves male and female aspects.

For a basic roundup of posts on the Li family Daoists, see here.