Further notes on fieldwork

A tribute to Antoinet Schimmelpenninck (1962–2012)

revised version of a talk I gave at the CHIME conference in Leiden, 2012

Amdo-Tibetan area, south Gansu, 2001 (photo: Frank Kouwenhoven).

I never did any fieldwork with Antoinet, but I admired and envied her natural engagement with musicians and with people altogether.

I won’t portray her as some kind of Lei Feng, so this can also be a kind of homage to, and reflection on, fieldwork itself. And I will discuss her alone, whereas of course she and her partner Frank Kouwenhoven, dynamic leaders of CHIME in Leiden, made an indivisible team.

Almost anything can be fieldwork, such as talking to your mum, or your kids, or going clubbing—although we’re perhaps unlikely to undertake all three at the same time. But I refer here to spending time with Chinese musicians in the countryside, which requires a rather different set of skills from hanging out with rock musicians in Beijing, for instance.

Fieldwork by the Chinese on their local musical traditions, in a sense that we can recognize, goes back to at least the 1920s. But when we laowai began to join in in the 1980s, it was exciting to get some glimpses of local folk traditions. We can see that sense of discovering a “well-kept secret” right from Antoinet’s articles in early issues of CHIME. [1]

All these years later, I suspect local traditions are still largely a well-kept secret, and that may not be an entirely bad thing. But fieldwork by the Chinese has also thrived since the 1980s; plenty of Chinese are doing great work. In those early days, Chinese fieldwork was rather mechanical: the main object was to collect material in the form of musical pieces, conceived of as rather fixed and somewhat detached from changing social context. Antoinet was at the forefront of broadening the subject; the title of her book, Chinese folk songs and folk singers, is significant. This inclusion of the performers in the frame has borne fruit in Chinese and foreign work.

Among general skills, we might list

- preparation (finding available material, maps, preparing questions, etc.)

- linguistic competence (how I envied her ability to communicate, and latch onto regional dialect)

- musicality (and “participant observation”; routine for us, rare among Chinese scholars)

- back home: analysis/reflection; sinology and ethnomusicogical/anthropological theory

In addition to my citings of Bruce Jackson and Nigel Barley (Fieldwork, under Themes), further reflections include:

- Helen Myers in Ethnomusicology: historical and regional studies (New Grove Handbooks on Music)

- Barz and Cooley, Shadows in the field

- Lortat-Jacob, Sardinian Chronicles

- Don Kulick and Margaret Willson (eds.), Taboo: sex, identity and erotic subjectivity in anthropological fieldwork.

As to what is ponderously known as “participant observation”, musicians tend to react well to other musicians—it shows a willingness to engage, and also helps us think up useful questions.

As to what we do after fieldwork: Antoinet was well grounded in ethnomusicological readings, but she was never controlled by theory, she used it critically to illuminate points, as one should. Scholarship is not always like that! Her book really is an amazing achievement. She not only broadened the subject, she made it more profound.

Rapport

A lot has been written about personal interaction in fieldwork. I like Bruce Jackson’s book very much. We all have different personalities; some of us may seem more outgoing than others. It’s an unfair accident of birth, upbringing, and all that. Musicians will be more forthcoming with people they feel comfortable with—like Antoinet. Of course fieldwork manuals talk about good guanxi, but it’s more. We respect people that we talk to, but we also aspire to some sort of equality; we hope to be neither obsequious nor superior. On the agenda here are sociability, informality, amateurism, humanity/fun/enthusiasm/empathy, and humour—all without naivety or romanticism!

We do naturally adapt our behaviour to different situations. I’m much more sociable in China than in England. Antoinet, it seems to me, never needed to adapt, she was just always naturally gregarious and sparkling.

Age is an interesting factor: I guess it’s good to be old or experienced enough to be taken seriously, but intelligence and sincerity are appreciated, and it’s also good to be young enough, at least at heart, not to seem too important! Antoinet was always self-effacing, companiable.

I do bear in mind Nigel Barley’s warning (The innocent anthropologist, p.56):

Much nonsense has been written, by people who should know better, about the anthropologist being “accepted”. It is sometimes suggested that an alien people will somehow come to view the visitor of distinct race and culture as in every way similar to the locals. This is, alas, unlikely. The best one can probably hope for is to be viewed as a harmless idiot who brings certain advantages to this village.

By the way, I’m not a harmless idiot, I often feel like a harmful idiot: I hope it’s a coincidence that everywhere I go, the local traditions go down the drain…

Our ways of repaying all this hospitality are variable, depending on our means and inclinations. One may send photos and videos, and organise tours; Chinese colleagues have gone so far as to install running water, or find urban jobs for relatives.

I note some some handy Maoist clichés linking fieldwork and Communist ideals:

- chiku 吃苦 “eating bitterness”

- santong 三同 “the three togethers” (eating, living, and labouring together. Hah!)

- dundian 蹲点 (“squat”; more generously defined in my dictionary as “stay at a selected grass-roots unit to help improve its work and gain firsthand experience for guiding overall work”. How long is this dictionary?!)

- gen qunzhong dacheng yipian 跟群众打成一片 “becoming at one with the masses”

- bu na qunzhong yizhenyixian 不拿群众一针一线 “not taking a single needle or thread from the masses”

My point here is to get over the empty formalism of such slogans and see through to the sincere humanity that once inspired them.

These thoughts on empathy aren’t something we can do much about, but it’s interesting to reflect on the topic. Obviously enthusiasm isn’t enough; on its own it can be quite irritating!

I guess we all use teamwork to some extent, and Antoinet was good at finding, and supporting, good regional and local scholars to work with. I have always relied heavily on my Beijing colleagues to make notes, at least until circumstance and greater familiarity lend me the confidence to spend time with musicians on my own.

Group fieldwork is good up to a point. It depends partly on one’s means, but the group perhaps shouldn’t be too large. I like the informality and flexibility of working alone, but it is a bit much to take photos and videos and make notes and distribute fags all at once.

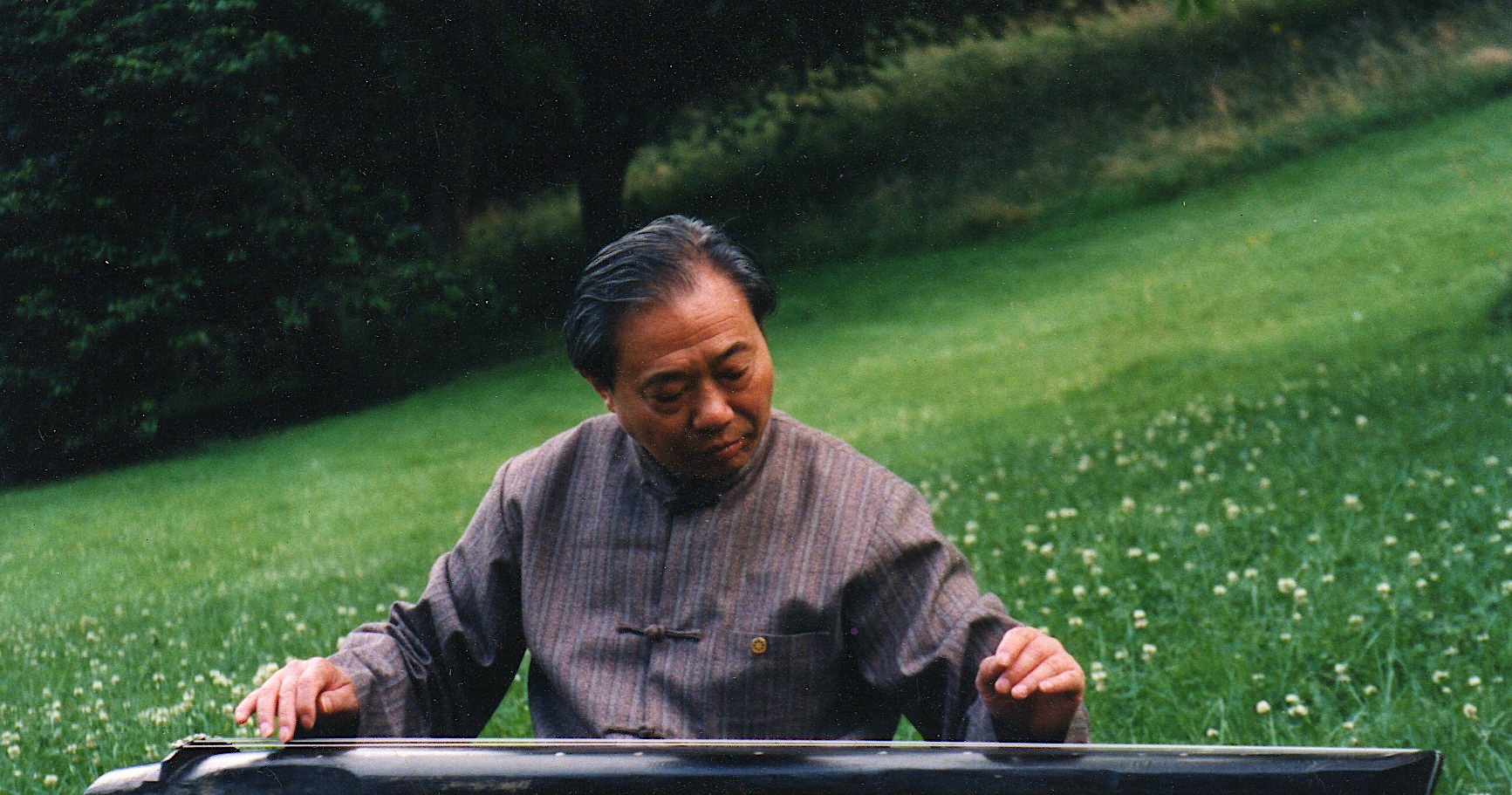

Of course Antoinet was interested in all kinds of music-making, but she was among few laowai who did much work outside the main urban areas. Her two main fieldwork areas were very different: in south Jiangsu she found herself mainly doing a salvage project, but in Gansu she found a ritual scene that is very much alive.

As to time-frame, she and Frank mainly made repeated visits over time, and as I did for Plucking the Winds or my work with the Li family. Talking of Plucking the Winds, I’ve never had such a perceptive meticulous and patient editor as Antoinet.

Obviously, a brief interview with a stranger is likely to yield less interesting or reliable results than long-term acquaintance. But I do take on board the notion of stranger value. On one hand (Jackson, Fieldwork, pp.69–70, after Goldstein),

The collector who comes from afar and will disappear again will be able to collect materials and information which might not be divulged to one who has a long-term residence in the same area.

On the other hand, there’s the whole “You will never understand this music” thing (Nettl, The study of ethnomusicology, ch.11, brilliant as ever).

And then, who is an insider? What of urban Chinese? How might an urban-educated male Fujianese get along with female spirit mediums in rural Shanxi, and so on?! There are several complex subjects for discussion here.

Talking of etic questioning, here’s another vignette from the Li band’s 2012 tour of Italy (my book p.336):

Third Tiger is as curious as ever, always asking weird “etic” questions like “Why are Italian number-plates smaller at the front than at the back?” Bemused, I later ask several Italian friends, who have never noticed either. It strikes me that this is probably just the kind of abstruse question that we fieldworkers ask all the time, and I’m sure my enquiries in Yanggao sound just as fatuous. I must cite Nigel Barley (The innocent anthropologist, p.82)—and note the car link:

They missed out the essential piece of information that made things comprehensible. No one told me that the village was where the Master of the Earth, the man who controlled the fertility of all plants, lived, and that consequently various parts of the ceremony would be different from elsewhere. This was fair enough; some things are too obvious to mention. If we were explaining to a Dowayo how to drive a car, we should tell him all sorts of things about gears and road signs before mentioning that one tried not to hit other cars.

By the way, I was the victim of a flawed fieldwork interview some years ago. A Korean student, whom I knew fairly well, was doing an MA on ethnomusicology in London, and had to do an interview. She knew I was both a violinist and did fieldwork on Chinese music, so she came over to my place with a list of questions all prepared. Her English wasn’t great—like, even worse than my Chinese. OK, her project demanded quite a short interview.

She began with “Who is your favorite composer?” and I went, “Well, music is more about context, mood, not compositions, and anyway I don’t listen to so much WAM these days, and most music in the world we don’t really know of a “composer”… OK, if you insist, then Bach.” She went, “Thankyou. What was the best concert you ever done?” so I observed that we don’t do so many memorable concerts over a year, and that great music-making doesn’t only happen in concerts. “Being an orchestral musician can be frustrating, one’s teenage idealism tends to get beaten down, getting a plane, then five minutes in the hotel before a long rehearsal with a boring conductor, no time to eat properly… You could ask me, what was the most wonderful musical experience I have had—it wouldn’t necessarily be playing with an orchestra…” In response to this cri de coeur, she went on, “Thankyou. What is the difference between the Western violin and the Chinese violin?” Aargh. I mean, anyone would want to follow up on all that I had just said, right? But her rigid questionnaire was in control.

So is that what I have been doing in China all these years—misunderstanding, ignoring leads, and following up with my own stupid blinkered questions?!

One hopes to find questions that will get people talking at length (so avoid questions that invite simple Yes/No answers!); but there was I blabbering on, and all she wanted was short snappy answers!

I’m still very attached to the detailed notes of my Chinese colleagues. One can’t record everything on audio or video, and even if we could, it would leave unclear how many characters should be written. I used to use video mainly to film ritual—I only began to record informal situations later. Antoinet was great at bypassing formality.

They recorded all kinds of things as well as formal singing sessions, and sure they had the means to do that, as well as recruiting helpers and so on.

A questionnaire is essential, [2] but it must always be flexible, following their flow, always thinking of new questions, how to express them suitably, and listening. All of which Antoinet was brilliant at.

For me fieldwork is a constant discovery of how inaccurate and superficial my previous notes were. Antoinet and Frank’s enquiring spirit can be seen in these reflections that Frank later sent me:

We had no such thing as a “method”—in general we did tend to visit singers more than one time, preferably many times, in order to ask them the same questions repeatedly, and to let them sing the same songs more than once, with intervals of days, weeks, months or even years in-between. That was only possible with individual songs, of course, not with spontaneous dialogue songs, which we got acquainted with mainly in Gansu.

I think we learned most from what people told us spontaneously, about their own lives, in personal conversations, which were not strictly private conversations. People are nearly always in a space together with others. But group interviews (group chats, rather) were good, people felt at ease, they were not “attacked” by us, they were simply chatting…

Basically, in our fieldwork, we were always out to discover what we were not aware of yet. That is a hard task. And I think we kept discovering that we had not yet asked the right questions, had not investigated the right topics yet… Even now do I realize that I should go back… Maybe this is only the natural, classic, condition for fieldworkers: you return home with an idea of how things might be, you end up with an hypothesis, you suddenly stumble upon a new hypothesis which sheds new light on the situation, but then you have to go back again to test it, and the work starts all over again… A never-ending process, also because the questions you ask are nearly always bigger than the time and resources you have, and you need to address your problems piecemeal… We often wished we were five hundred people!

By the way, do watch their beautiful film Chinese shadows: the amazing world of shadow puppetry in rural northwest China (Pan, 2007).

In short, fieldwork may be an unending amount of work, but it’s endless inspiration too: and one works better when inspired. So I hope we can keep Antoinet’s spirit alive by emulating her humanity, enthusiasm, and critical intelligence.

For a recent volume on doing fieldwork in China, see here. And note the folk-song research of Qiao Jianzhong.

[1] Or for Daoist ritual, see e.g. the early fieldwork of Kenneth Dean.

[2] For her sample questionnaire for southern Jiangsu, see Chinese folk songs and folk singers, pp.395–6. Cf. McAllester’s questionnaire for the Navajo.