I have already mentioned my encounter with a stammering shawm player in Shaanbei.

As a stammerer, I’m all for a good stammering joke. Now as a limerick this is no big deal:

But sung as a round, in the fine melody to which it was set, it can be brilliant, with its syncops and manic pile-ups of unconnected final words.

I say “can be”… It sounds great sung in the gentle polished affectionate tones of my Oxbridge chums, one to a part. But for us stammerers, the regimented impersonal nature of such a rendition by a large school choir may seem mesmerizingly traumatic. One imagines poor stammering schoolkids cowering red-eyed with fear in the corner, their anxious parents in the audience. Anyway, let’s just imagine it sung kindly with humour… As usual, it’s all about context, and the intentions of performers and audiences.

It’s easy for you to say that, Steve…

It’s well known that stammerers can sing fluently—indeed, most can do silly voices too, although that’s hardly a long-term solution. I note too that stammering is predominantly male; and that it is also common in Japan, another highly pressurized island culture.

“Stammer” or “stutter” is another instance of US/UK English variation.

And further to the collation of Daoist texts, a note on textual variation: some versions open “There was an old man from Calcutta”. Stammering tends to decline with age—though for sufferers like me it takes variant forms. One wonders whether the old man was an expat, or native to Calcutta; if the latter, his fondness for dairy products may be merely an Raj-esque affectation, or else it may indicate a predilection for paneer and ghee—but that would scupper the p-p-poem.

For a more avant-garde take on stammering, see here; and for the brilliant fugal pastiche Donald Trump is a wanker, here.

You’ll be glad to know that our encyclopaedic resident publication The China Daily covers stammering too:

Feng Kezhi, a 24-year-old garage worker, suffered stammering so much that he once stood in the pouring rain and kept slapping his face but this didn’t cure him. It was Wang’s clinic that brought back his confidence. “There are many people like Feng who need a helping hand and I must try my best to help them”, Wang said.

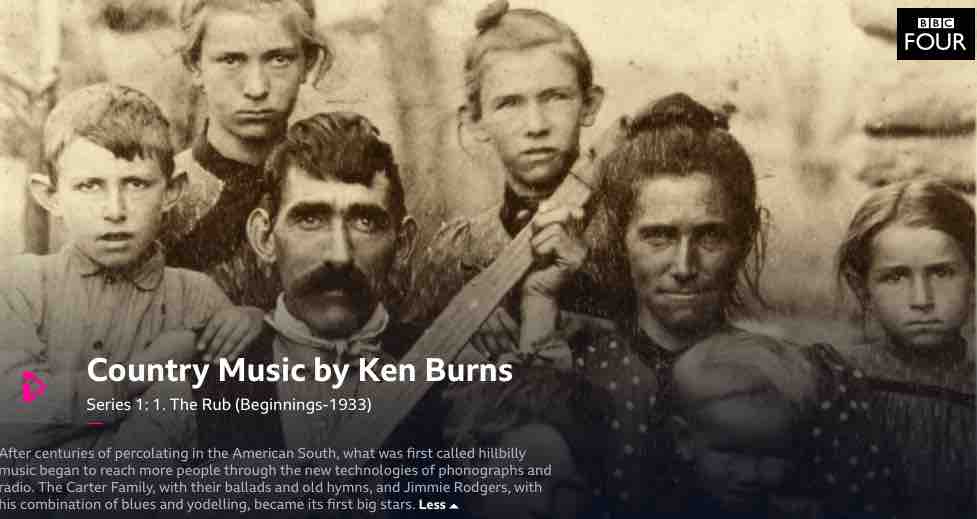

China presents a fine challenge for stammerers like me. When the English are confronted by a ferocious bout of stammering, polite embarrassed sympathetic reactions are de rigueur—immortalized by the finely-observed scene in A Fish called Wanda:

Conversely, the Chinese just tend to burst out laughing, a nice honest response.

What’s more, whereas in England we fiendishly covert stammerers can usually get away with limiting our conversations to one or two people, in China one is rarely in a group of less than a dozen; so short of feigning dumbness or unconsciousness, it’s not really possible to avoid public talking. It’s rather good shock therapy: “We have ways of making you talk”—which was of course the motto of the S-S-Stammering Association (hence also the name SS). Progress is only possible once one begins to stammer openly.

It’s good to hear Ed Balls talking (openly, and fluently) about his stammer (see also here):

He joins the ranks of distinguished stammerers like Moses, Demosthenes, the Byzantine emperor Michael II, Wittgenstein, Somerset Maugham, Marilyn Monroe, Kylie Minogue, Maggie O’Farrell, Joe Biden, Amanda Gorman, * and JJJJJerome Ellis—and for China, see here. There’s another fantasy dinner party, hosted by Michael Palin—a notable advocate for stammering, and the greatest ambassador anyone could ever have for anything.

The excellent British Stammering Association used to run a cartoon series called Stammering Stan, which was somewhat controversial. But this will be evocative for stammerers:

Li Manshan has a brilliant stammering joke, which he loves telling me—but it’s best if you hear him tell it himself…

For more stammering songs, click here and here. See also the stammering tag, including this post on chipping away at the iceberg of fear.

* Update: 13-year-old stammerer Brayden Harrington just made a powerful speech for the 2020 Democratic National Convention:

* Another update: in The speaking voice, do listen to the brilliant Amanda Gorman, erstwhile stammerer, at the 2021 Inauguration!