The upcoming CHIME conference in LA (29 March to 2 April), presided over by the excellent Helen Rees, looks like a fine event, though I can’t make it. The theme this time is festivals.

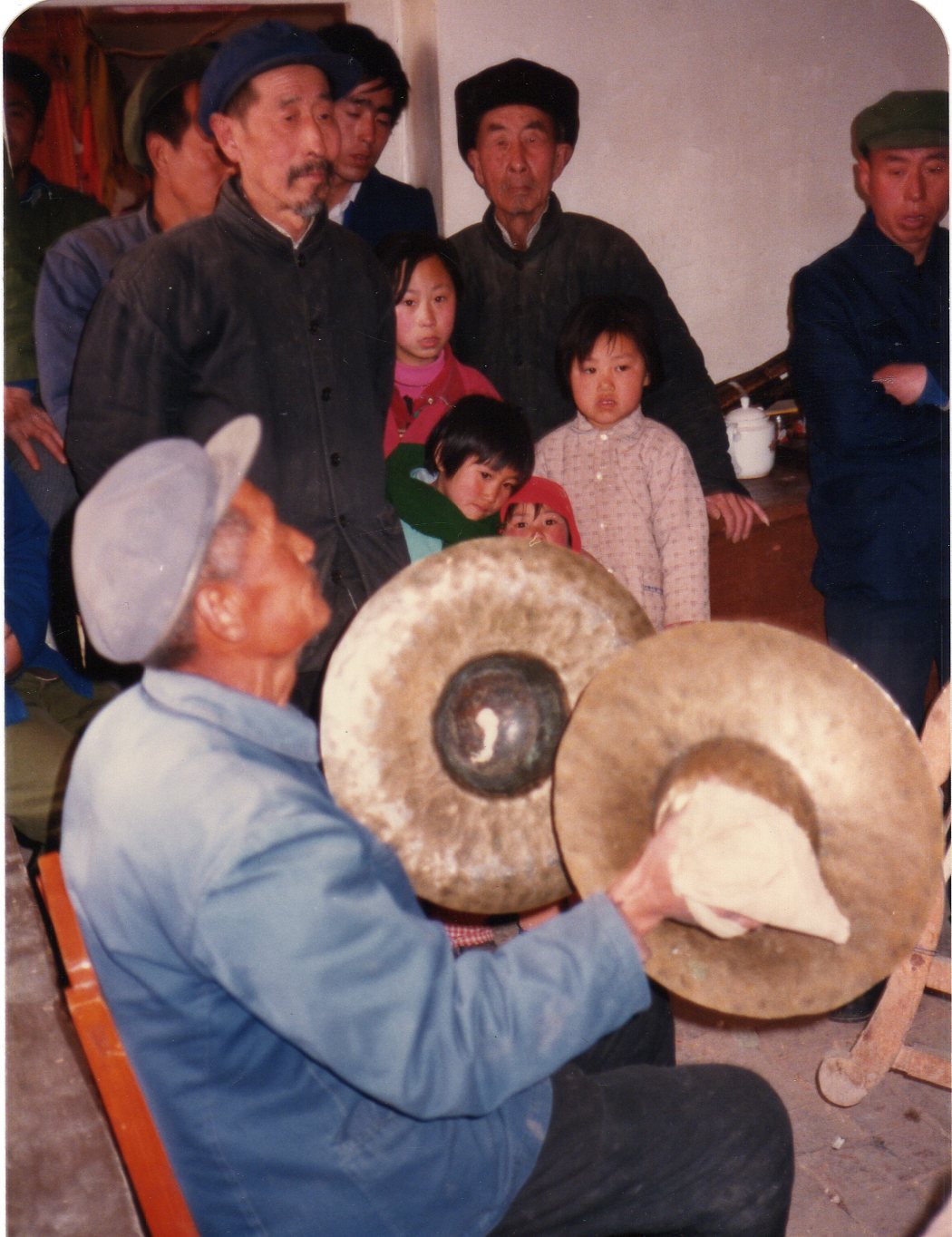

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997. [1]

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997. [1]

Photo: Frank Kouwenhoven. © CHIME, all rights reserved.

Of course, festivals and pilgrimages all over the world are a major theme of ethnography: not just Uyghur meshreps and mazar, and Tibetan monastery festivals, but Indian melas, Sufi festivals, the Mediterranean (Andalucian fiestas, south Italy…), Moroccan ahouach, you name it. Bernard Lortat-Jacob’s 1994 book Musiques en fête is charmant, with wise and vivid words about Morocco, Sardinia, and Romania (¡¿BTW, why do French books put the list of contents at the back?! ¡¿Typical Gallic contrariness?!)

To adopt the metaphor of “the whole dragon” again, there is a long continuum between folk festivals, based on ritual (often calendrical) observances, and secular events for a largely urban audience.

So I too am going to link up diverse themes like temple fairs, ritual, famine, village names, Eurovision, and propaganda. It does make sense, though—trust me, I’m a doctor.

Traditional events in China`

Funeral rituals have been my main topic in China for thirty years, but of course it’s not easy to plan visits much in advance. The calendrical dates of temple fairs (often known as miaohui) may seem easier to anticipate. Again, scholars of religion tend to home in on their specifically religious elements, as in the great jiao Offering—though note Ken Dean’s fine film Bored in heaven. But like funerals they are multivalent, embracing all kinds of activity: ritual, opera, folk-song, pop, commerce, “hosting” and “red-hot sociality” (Chau!)…

Apart from my 2007 and 2009 books, names like Zhao Shiyu, Guo Yuhua, Wang Mingming, Yue Yongyi, Stephan Feuchtwang, Adam Chau, and Wu Fan spring to mind. The knack is to detail both sacred and secular aspects of temple fairs.

But the dates of calendrical rituals, like temple fairs, may not be easily vouchsafed to the outsider either. The temple fairs on the Houshan mountains in Yixian county southwest of Beijing, mainly in the 3rd and 7th moons, are much less well known than those of Miaofengshan, but they also draw huge crowds, both local and from further afield.

To work all this out you have to spend time around the villages of Liujing and Matou in the foothills around Houshan, and then observe who goes where when and does what. Although Chinese villagers are a rich source of ritual and musical information (far more than any silent library), they often speak prescriptively rather than descriptively, telling us on what occasions a jiao Offering ritual should be performed, whether or not is has been performed since the 1940s. They don’t necessarily volunteer information on change, preferring (like some officials and scholars) to present their traditions as constant, eternal—even if contexts and repertoires have evidently changed in their lifetime. On our first visit to Liujing we rather assumed that villagers’ descriptions of ritual pilgrimages related to “the past”— but we soon found that they were very much alive.

The Songs-for-winds associations: propaganda and catastrophe

What got me “thinking” (I use the word loosely) about all this was that 1950 visit to Tianjin of the “Songs-for-winds” band from Ziwei village, in what later became Dingxian county.

The Central Conservatoire (as it was then) was then still based at Tianjin, of course. The work of Yang Yinliu and Cao Anhe on the Songs-for-winds may be considered a prelude to that on the more solemn ritual style of the Beijing temples that Yang undertook from 1952, a topic that was to expand vastly after 1986. But the Songs-for-winds groups, more popular than the ritual style that is my main focus, are worth a little detour here.

We should bear in mind that such wind ensembles were quite unfamiliar to southerners like Yang and Cao. Having invited the Ziwei band to the conservatoire, they recorded their repertoire on a Webster wire recorder. The band went back some six generations, and under the leadership of the celebrated Wang Chengkui, they had invited the great wind player Yang Yuanheng to teach them in the winters of 1945 and 1946. Yang Yuanheng, a former Daoist priest in a little temple in Anping county, was himself appointed professor of guanzi oboe at the conservatoire in 1950. [2] Yang Yuanheng, like the Buddhist monk Haibo, was a major influence on many shengguan ritual associations in the area: we would hear their names from many village associations.

Yang and Cao’s monograph on the Ziwei band, published in 1952, consists mainly of transcriptions, with little of the social detail that they covered for the Wuxi Daoists or Yang’s 1956 Hunan fieldtrip. Ziwei would go on to supply wind players to many state troupes for decades to come.

Secular New Year’s huahui parade, Langfang city, 1991.

Xushui

Adapted from my Folk music of China (p.196):

During the 1958 Great Leap Forward (or Backward, as it’s known), Dingxian and particularly Xushui counties became model counties for the relentless drive to full communization. [3] At the height of the Leap back in August 1958, Chairman Mao visited communes there. In Dasigexiang district just southeast of Xushui county-town, Dasigezhuang village was now renamed the 4th August brigade. Notable for its revolutionary fervour at this time was the “Great Leap Forward Songs-for winds association” of Qianminzhuang brigade in Xushui, which performed for this visit.

The propaganda of the Leap makes a stark contrast with the grim realities of the period, with villages throughout the area suffering from crop failure, famine, and social disruption.

Our visit to Qianminzhuang in 1993 was the only time I’ve ever had a police escort—to take me there for a change, not to drag me away! Predictably, such an effusive welcome for me as a “foreign guest” indicated close supervision and censorship of our fieldwork.

Striking a pose with the leaders, Qianminzhuang 1993

In 1995 we visited some of the senior musicians independently, with much more useful results.

Xushui’s favoured status did nothing to prevent many starving to death there in 1960—but just near Qianminzhuang, the Gaozhuang ritual association still managed to restart in 1961. Religion revived in China precisely at moments of political crisis such as the famines of 1960 and the Cultural Revolution, albeit with great difficulty. It may provide solace, or a focus for resistance—both against Maoism and later against the insecurities ensuing its demise.

The Gaozhuang ritual association was one of many in Xushui villages that used, and use, the older more solemn shengguan style. Ritual associations throughout the area commonly claim transmission from either Buddhist monks (heshangjing 和尚經) or Daoist priests (laodaojing 老道經)—the Gaozhuang association is Buddhist-transmitted. In another common taxonomy, the association divides into “front altar” (qiantan, the shengguan instrumental ensemble, and “rear altar” (houtan, vocal liturgy).

Despite its revolutionary image, Xushui county has remained a hotbed for religion, notably the cult of the sectarian creator goddess Wusheng laomu. Associations there commonly hang out ritual paintings, like the Ten Kings (Shiwang) or Water and Land (Shuilu) series, and they use “precious scrolls” and other ritual manuals. They too are within the catchment area of Houtu worship—they used to make the pilgrimage to Houshan. Even the revolutionary Qianminzhuang band told us that their former tradition was to recite the scriptures, performing only as a social duty for funerals, not for weddings. And certainly not to accompany mendacious parades to report a bumper harvest…

In 1994 the Gaozhuang association built an Ancestral Hall to Venerable Mother (Laomu citang), occupying about one mu, stylish and grand. It cost around 60,000 kuai to build; the stele lists 132 donors, who gave from 50 up to 3,000 kuai. The altar has Wusheng laomu in the centre, Wangmu niangniang and Songzi niangniang to the right, Cangu niangniang and Houtu niangniang to the left.

The village Party Secretary told us that sources of support included incense money from the Great Tent Association (Dapeng hui, a common term in the area for a ritual association) and from the temple, and money from fortune-telling and curing illness. He reflected, “A dozen or so women kept on coming to see me about building a temple. I had no choice—the brigade couldn’t refuse, so I gave them a plot of land. Believing in the gods and having a temple is no bad thing, it’s not as if you stop production if you believe in it!”

In all, the flamboyant (and readily secularized) Songs-for-winds style remains a common image of wind bands on the Hebei plain, but since all our fieldwork through the 1990s it is clear that ritual practice, with its more solemn shengguan instrumental style, is both older and more common. It is resilient too. This persistence of tradition, both in religious and musical practice, is all the more striking in such a once-revolutionary county as Xushui.

Mao was impressively modest about his limited success when he admitted to Nixon in 1972:

“I haven’t been able to change [China]—I’ve only been able to change a few places in the vicinity of Peking.” [4]

But he wasn’t modest enough: in some ways even a county so near Beijing, such a focus of the revolution, has remained resistant to Maoist ideology, predating and outliving it. Still, disruption was severe. For more on Xushui, see here.

Official festivals in the 1950s

Meanwhile, the new government, in its own way, was promoting local culture through the medium of regional folk festivals (diaoyan, huiyan). First, local festivals were held to select representatives for major performances in the regional capitals. Some laicized priests were even assembled to perform as “troupes“, sometimes for the first time in many years—such as Baiyunshan Daoists (1955), Wudangshan Daoists (1956 and 1957), Wutaishan Buddhists (1958). For such performances, inevitably, their shengguan instrumental music was plucked out of its ritual context. I haven’t heard stories as distressing as the fate that befell kobzari blind minstrels in Ukraine when summoned for an official festival in the early 1930s; but folk ritual specialists were still anxious about performing for officials around 1980.

These festivals served partly as auditions for the state song-and-dance troupes then expanding all over China. Daoist and Buddhist ritual specialists had a deserved reputation as outstanding instrumentalists. Many, like our very own Li Qing (my book pp.113–25), were recruited as musicians to state troupes around 1958—and then sent home again as the state apparatus collapsed in 1962.

While such festivals stimulated the collection and documentation of folk music, we must balance this with the ongoing assaults on its traditional context. The background ( beginning from the 1940s) was campaigns against “feudal superstition”, terrifying public executions of sectarians, and the destruction of temple life.

The reform era

Urban festivals featuring rural groups—perhaps related to a conference—make a convenient recourse for busy academics into whose holidays they fit nicely. From the 1980s, the secular arts festivals of the Maoist era were remoulded into more glossy events. In 1990 the Li family Daoists took part in a festival of religious music in Beijing.

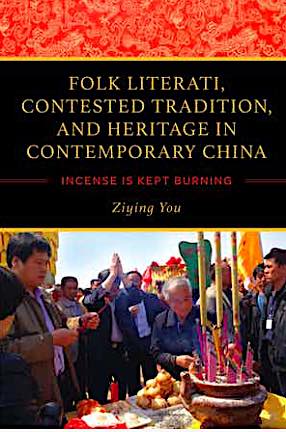

By the 21st century the new ideology was confirmed in the regular staged “living fossil” presentations of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. The latter project, with its whole bureaucratic workings, has now become a major research topic on its own, at the expense of studies of the local traditions that it is supposed to assist (my book pp.331–3). Note also the Qujiaying bandwagon.

I tend to steer clear of conferences, but in May 2016, as a pretext for going to hang out yet again with Li Manshan in Shanxi for a couple of weeks, I accepted an invitation to take part in a conference celebrating the 80th birthday of my esteemed teacher Yuan Jingfang in Beijing (for the resulting volume, see here).

It was a déjà-vu experience. Apart from a sequence of eulogies, the event also featured staged performances from three representatives of Yuan Jingfang’s long-term research areas: the Hanzhuang ritual association from Xiongxian in Hebei (near Xushui), the Zhihua temple group, and a ritual band from near Xi’an.

Filming the Hanzhuang association in their ritual tent, 1993 (photo: Xue Yibing). Rear centre: two frames of ten-gong yunluo.

It made me feel my age, reminding me of all our visits to these very groups between 1986 and 2001. Taking time out of the conference to chat with the Hanzhuang group outside by the lake, we recalled their kindly association leader Xie Yongxiang 解永祥, father of the present leader, and another of those wise sheng masters. We had learned a lot from him in 1993 and 1995.

Xie Yongxiang, 1995

But returning to the conference—the object of admiration, inevitably, was their “music”, detached from its enduring social context. I already missed hanging out with Li Manshan in the scripture hall.

All the glossy stage presentation has many Western parallels—flamenco on the Terry Wogan show, WOMAD, Songlines, prizes, urbane discourse explaining its “cultural value” to outsiders… The fancy costumes and dry ice of many Chinese events are reminiscent of Eurovision; they may seem like a Disneyland version of the Chinese heritage.

That photo comes from a recent ICH “performance” of the Baiyunshan Daoists, no less.

Now, I adore opportunities to present the Li family Daoist band on the concert platform (see e.g. this post and a whole related series of vignettes from May 2017), but while it is of course a compromise, we take care not to tart them up—we can hardly do otherwise, so solemn is their demeanour. The ambience and acoustic of churches makes a fine setting, the Daoists’ sheng mouth-organs filling the Peterskirche in Heidelberg on our 2013 tour (cf. Buildings and music):

The Li family Daoist band in concert, Heidelberg April 2013.

Still, their regular “rice-bowl”—day in, day out—is always performing funerals for their local, not global, clientele.

What is dodgy is when people begin mistaking the staged events for the Real Thing, or some kind of ideal. Urbanites may do so, but villagers know better. Of course those staged events are themselves a legitimate, and popular, object of scholarly analysis. But I worry that it creates a fait accompli, like the way that in old-school WAM musicology the Great Composers were the main story (as deconstructed by McClary, Small, Nettl)—“this is what we find, so it must reflect the real picture, and so this is the object of study”. As always, “modern” secular performance doesn’t replace traditional activity: they co-exist.

The CHIME conference in LA will doubtless turn up many instances of what I’m struggling not to call “contested negotiation”. Anyway, staged events can give us a lead, rather like using the photos in the Anthology, otherwise flawed, to draw us towards folk activity.

For thoughts on the theme of the 2021 CHIME conference, see here.

[1] For more, see Frank Kouwenhoven, “Love songs and temple festivals in northwest China: musical laughter in the face of adversity”, in Frank Kouwenhoven and James Kippen eds., Music, dance and the art of seduction.

[2] For this whole section, see my Folk music of China, pp.48–52, 195–203; “Chinese ritual music under Mao and Deng”, British Journal of Ethnomusicology 8 (1999): 27–66; “Reading between the lines: reflections on the massive Anthology of folk music of the Chinese peoples”, Ethnomusicology 47.3 (2003): 287–337. See also my In search of the folk Daoists of north China, pp.166–7, 183–4, 188–90.

[3] As correctives to all the Xushui propaganda, see e.g. the brilliant works of Friedman, Pickowicz, and Selden, Chinese village, socialist state and Revolution, resistance, and reform in village China—describing a commune not far from Xushui. Note Chinese village, socialist state, pp.215–20; Dikötter, Mao’s great famine, pp.40, 47–9, 68–70; and estimable analysis online in Chinese, e.g. http://mjlsh.usc.cuhk.edu.hk/book.aspx?cid=6&tid=184&pid=2269. For the model commune of Greater Quanshan in Shanxi, precursor of Dazhai, and temporary “home” to the Li family Daoists, see my Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.122–3, and here, under “Famine in China”.

[4] Also reported by Henry Kissinger in Newsweek, 3rd March 1997, p.31.

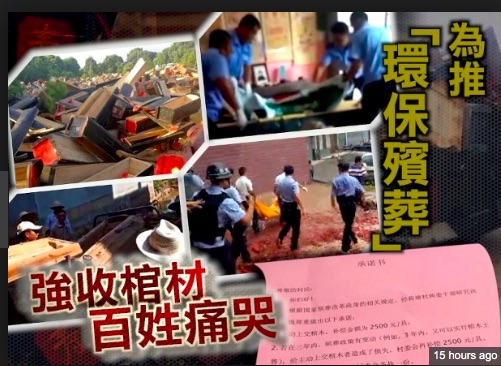

So while there are complex issues at work here, the recent directive illustrates a common befuddled knee-jerk response from local government. If they’re so keen on harking back to Maoist values, they might instead consider a re-education campaign for cadres—it is they who now lead the way in “vulgarity” and

So while there are complex issues at work here, the recent directive illustrates a common befuddled knee-jerk response from local government. If they’re so keen on harking back to Maoist values, they might instead consider a re-education campaign for cadres—it is they who now lead the way in “vulgarity” and

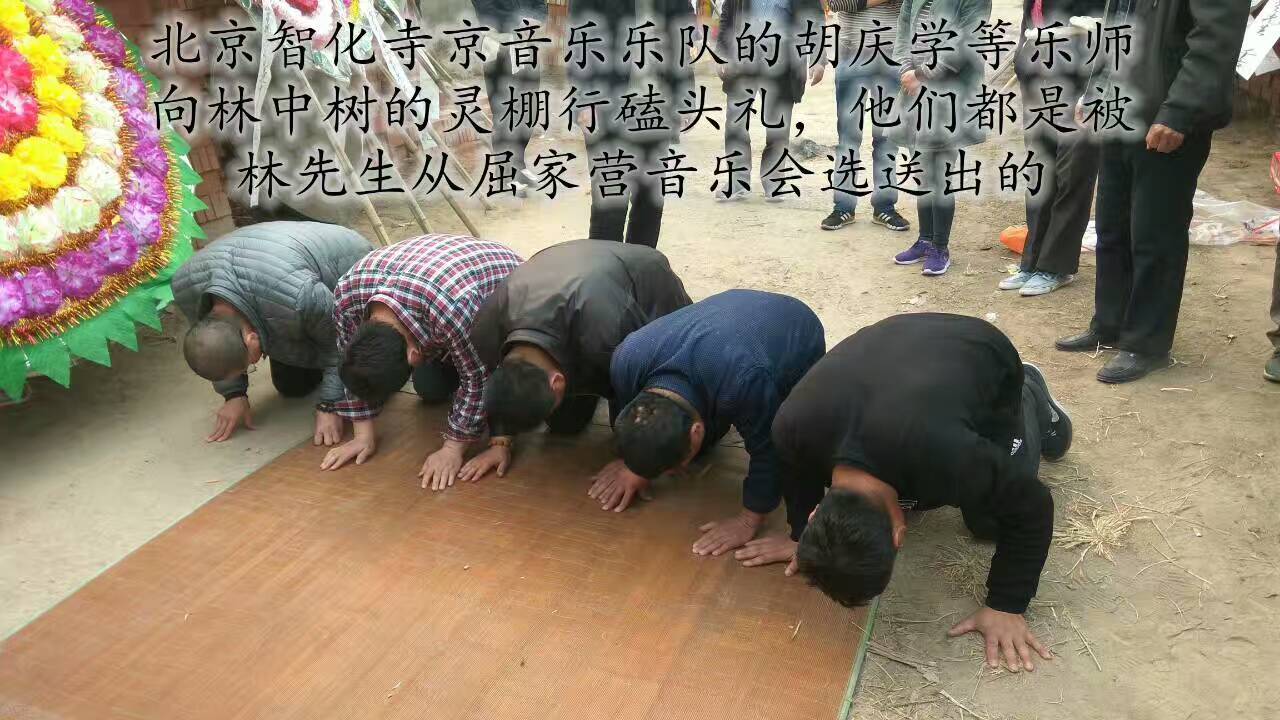

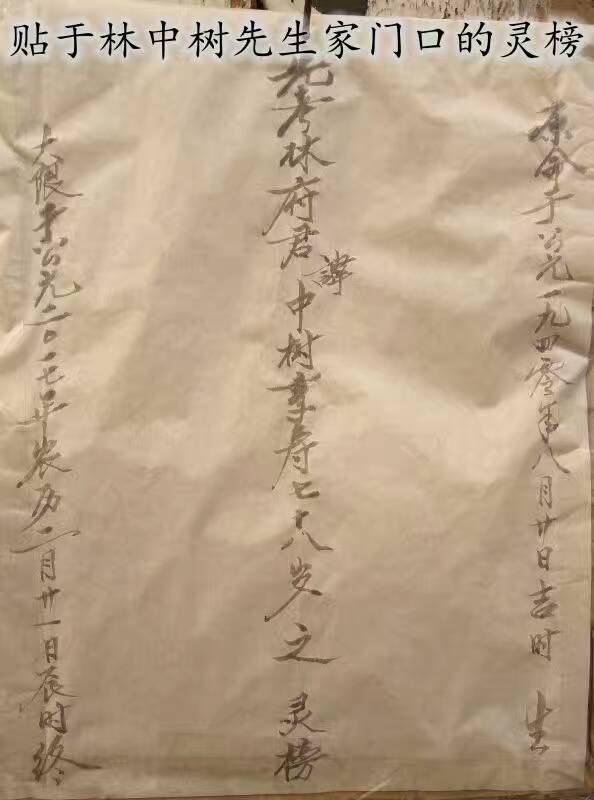

Led by Hu Qingxue, Qujiaying villagers, later trained in the Zhihua temple style, kowtowing before the soul hall at Lin Zhongshu’s funeral, and playing the classic sequence Jinzi jing, Wusheng fo, and Gandongshan.

Led by Hu Qingxue, Qujiaying villagers, later trained in the Zhihua temple style, kowtowing before the soul hall at Lin Zhongshu’s funeral, and playing the classic sequence Jinzi jing, Wusheng fo, and Gandongshan.

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997.

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997.