Just essayed a little homage to Turangalîla, under WAM>Messiaen.

Category Archives: China

New definitions

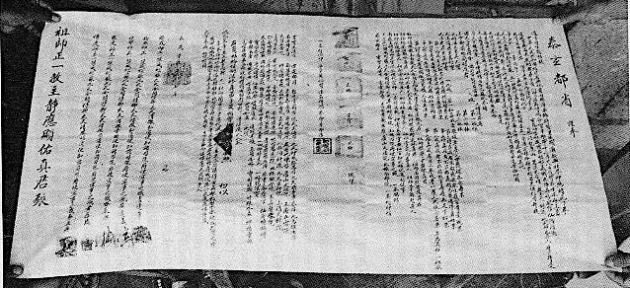

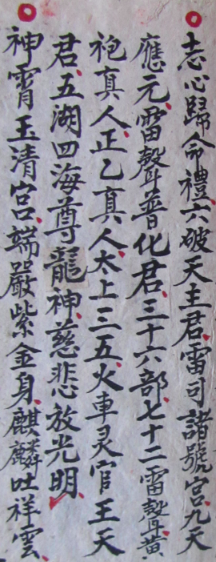

Daoist ordination certificate, Putian.

Source: Kenneth Dean, Taoist ritual and popular cults of southeast China.

In the spirit of I’m sorry I haven’t a clue…

Further to Speaking from the heart, where I noted the somewhat elaborate definition of the term dundian, here’s another fine definition—ironically, from the Chinese-Chinese dictionary of my Daoist master Li Manshan, no less, which we consulted when I mentioned the term lu 籙, Daoist “registers” (lengthy hereditary titles bestowing the authority to conduct rituals), unfamiliar to him (my translation):

a superstitious thing that Daoists use to trick people

Hmm. Li Manshan shrugs, and we both giggle.

Speaking from the heart

Further notes on fieldwork

A tribute to Antoinet Schimmelpenninck (1962–2012)

revised version of a talk I gave at the CHIME conference in Leiden, 2012

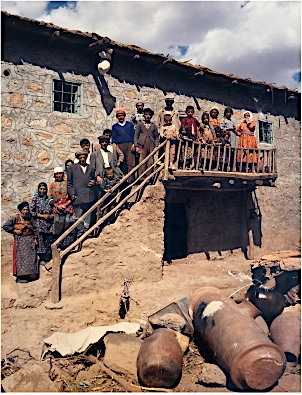

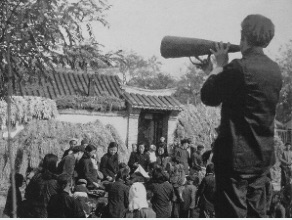

Amdo-Tibetan area, south Gansu, 2001 (photo: Frank Kouwenhoven).

I never did any fieldwork with Antoinet, but I admired and envied her natural engagement with musicians and with people altogether.

I won’t portray her as some kind of Lei Feng, so this can also be a kind of homage to, and reflection on, fieldwork itself. And I will discuss her alone, whereas of course she and her partner Frank Kouwenhoven, dynamic leaders of CHIME in Leiden, made an indivisible team.

Almost anything can be fieldwork, such as talking to your mum, or your kids, or going clubbing—although we’re perhaps unlikely to undertake all three at the same time. But I refer here to spending time with Chinese musicians in the countryside, which requires a rather different set of skills from hanging out with rock musicians in Beijing, for instance.

Fieldwork by the Chinese on their local musical traditions, in a sense that we can recognize, goes back to at least the 1920s. But when we laowai began to join in in the 1980s, it was exciting to get some glimpses of local folk traditions. We can see that sense of discovering a “well-kept secret” right from Antoinet’s articles in early issues of CHIME. [1]

All these years later, I suspect local traditions are still largely a well-kept secret, and that may not be an entirely bad thing. But fieldwork by the Chinese has also thrived since the 1980s; plenty of Chinese are doing great work. In those early days, Chinese fieldwork was rather mechanical: the main object was to collect material in the form of musical pieces, conceived of as rather fixed and somewhat detached from changing social context. Antoinet was at the forefront of broadening the subject; the title of her book, Chinese folk songs and folk singers, is significant. This inclusion of the performers in the frame has borne fruit in Chinese and foreign work.

Among general skills, we might list

- preparation (finding available material, maps, preparing questions, etc.)

- linguistic competence (how I envied her ability to communicate, and latch onto regional dialect)

- musicality (and “participant observation”; routine for us, rare among Chinese scholars)

- back home: analysis/reflection; sinology and ethnomusicogical/anthropological theory

In addition to my citings of Bruce Jackson and Nigel Barley (Fieldwork, under Themes), further reflections include:

- Helen Myers in Ethnomusicology: historical and regional studies (New Grove Handbooks on Music)

- Barz and Cooley, Shadows in the field

- Lortat-Jacob, Sardinian Chronicles

- Don Kulick and Margaret Willson (eds.), Taboo: sex, identity and erotic subjectivity in anthropological fieldwork.

As to what is ponderously known as “participant observation”, musicians tend to react well to other musicians—it shows a willingness to engage, and also helps us think up useful questions.

As to what we do after fieldwork: Antoinet was well grounded in ethnomusicological readings, but she was never controlled by theory, she used it critically to illuminate points, as one should. Scholarship is not always like that! Her book really is an amazing achievement. She not only broadened the subject, she made it more profound.

Rapport

A lot has been written about personal interaction in fieldwork. I like Bruce Jackson’s book very much. We all have different personalities; some of us may seem more outgoing than others. It’s an unfair accident of birth, upbringing, and all that. Musicians will be more forthcoming with people they feel comfortable with—like Antoinet. Of course fieldwork manuals talk about good guanxi, but it’s more. We respect people that we talk to, but we also aspire to some sort of equality; we hope to be neither obsequious nor superior. On the agenda here are sociability, informality, amateurism, humanity/fun/enthusiasm/empathy, and humour—all without naivety or romanticism!

We do naturally adapt our behaviour to different situations. I’m much more sociable in China than in England. Antoinet, it seems to me, never needed to adapt, she was just always naturally gregarious and sparkling.

Age is an interesting factor: I guess it’s good to be old or experienced enough to be taken seriously, but intelligence and sincerity are appreciated, and it’s also good to be young enough, at least at heart, not to seem too important! Antoinet was always self-effacing, companiable.

I do bear in mind Nigel Barley’s warning (The innocent anthropologist, p.56):

Much nonsense has been written, by people who should know better, about the anthropologist being “accepted”. It is sometimes suggested that an alien people will somehow come to view the visitor of distinct race and culture as in every way similar to the locals. This is, alas, unlikely. The best one can probably hope for is to be viewed as a harmless idiot who brings certain advantages to this village.

By the way, I’m not a harmless idiot, I often feel like a harmful idiot: I hope it’s a coincidence that everywhere I go, the local traditions go down the drain…

Our ways of repaying all this hospitality are variable, depending on our means and inclinations. One may send photos and videos, and organise tours; Chinese colleagues have gone so far as to install running water, or find urban jobs for relatives.

I note some some handy Maoist clichés linking fieldwork and Communist ideals:

- chiku 吃苦 “eating bitterness”

- santong 三同 “the three togethers” (eating, living, and labouring together. Hah!)

- dundian 蹲点 (“squat”; more generously defined in my dictionary as “stay at a selected grass-roots unit to help improve its work and gain firsthand experience for guiding overall work”. How long is this dictionary?!)

- gen qunzhong dacheng yipian 跟群众打成一片 “becoming at one with the masses”

- bu na qunzhong yizhenyixian 不拿群众一针一线 “not taking a single needle or thread from the masses”

My point here is to get over the empty formalism of such slogans and see through to the sincere humanity that once inspired them.

These thoughts on empathy aren’t something we can do much about, but it’s interesting to reflect on the topic. Obviously enthusiasm isn’t enough; on its own it can be quite irritating!

I guess we all use teamwork to some extent, and Antoinet was good at finding, and supporting, good regional and local scholars to work with. I have always relied heavily on my Beijing colleagues to make notes, at least until circumstance and greater familiarity lend me the confidence to spend time with musicians on my own.

Group fieldwork is good up to a point. It depends partly on one’s means, but the group perhaps shouldn’t be too large. I like the informality and flexibility of working alone, but it is a bit much to take photos and videos and make notes and distribute fags all at once.

Of course Antoinet was interested in all kinds of music-making, but she was among few laowai who did much work outside the main urban areas. Her two main fieldwork areas were very different: in south Jiangsu she found herself mainly doing a salvage project, but in Gansu she found a ritual scene that is very much alive.

As to time-frame, she and Frank mainly made repeated visits over time, and as I did for Plucking the Winds or my work with the Li family. Talking of Plucking the Winds, I’ve never had such a perceptive meticulous and patient editor as Antoinet.

Obviously, a brief interview with a stranger is likely to yield less interesting or reliable results than long-term acquaintance. But I do take on board the notion of stranger value. On one hand (Jackson, Fieldwork, pp.69–70, after Goldstein),

The collector who comes from afar and will disappear again will be able to collect materials and information which might not be divulged to one who has a long-term residence in the same area.

On the other hand, there’s the whole “You will never understand this music” thing (Nettl, The study of ethnomusicology, ch.11, brilliant as ever).

And then, who is an insider? What of urban Chinese? How might an urban-educated male Fujianese get along with female spirit mediums in rural Shanxi, and so on?! There are several complex subjects for discussion here.

Talking of etic questioning, here’s another vignette from the Li band’s 2012 tour of Italy (my book p.336):

Third Tiger is as curious as ever, always asking weird “etic” questions like “Why are Italian number-plates smaller at the front than at the back?” Bemused, I later ask several Italian friends, who have never noticed either. It strikes me that this is probably just the kind of abstruse question that we fieldworkers ask all the time, and I’m sure my enquiries in Yanggao sound just as fatuous. I must cite Nigel Barley (The innocent anthropologist, p.82)—and note the car link:

They missed out the essential piece of information that made things comprehensible. No one told me that the village was where the Master of the Earth, the man who controlled the fertility of all plants, lived, and that consequently various parts of the ceremony would be different from elsewhere. This was fair enough; some things are too obvious to mention. If we were explaining to a Dowayo how to drive a car, we should tell him all sorts of things about gears and road signs before mentioning that one tried not to hit other cars.

By the way, I was the victim of a flawed fieldwork interview some years ago. A Korean student, whom I knew fairly well, was doing an MA on ethnomusicology in London, and had to do an interview. She knew I was both a violinist and did fieldwork on Chinese music, so she came over to my place with a list of questions all prepared. Her English wasn’t great—like, even worse than my Chinese. OK, her project demanded quite a short interview.

She began with “Who is your favorite composer?” and I went, “Well, music is more about context, mood, not compositions, and anyway I don’t listen to so much WAM these days, and most music in the world we don’t really know of a “composer”… OK, if you insist, then Bach.” She went, “Thankyou. What was the best concert you ever done?” so I observed that we don’t do so many memorable concerts over a year, and that great music-making doesn’t only happen in concerts. “Being an orchestral musician can be frustrating, one’s teenage idealism tends to get beaten down, getting a plane, then five minutes in the hotel before a long rehearsal with a boring conductor, no time to eat properly… You could ask me, what was the most wonderful musical experience I have had—it wouldn’t necessarily be playing with an orchestra…” In response to this cri de coeur, she went on, “Thankyou. What is the difference between the Western violin and the Chinese violin?” Aargh. I mean, anyone would want to follow up on all that I had just said, right? But her rigid questionnaire was in control.

So is that what I have been doing in China all these years—misunderstanding, ignoring leads, and following up with my own stupid blinkered questions?!

One hopes to find questions that will get people talking at length (so avoid questions that invite simple Yes/No answers!); but there was I blabbering on, and all she wanted was short snappy answers!

I’m still very attached to the detailed notes of my Chinese colleagues. One can’t record everything on audio or video, and even if we could, it would leave unclear how many characters should be written. I used to use video mainly to film ritual—I only began to record informal situations later. Antoinet was great at bypassing formality.

They recorded all kinds of things as well as formal singing sessions, and sure they had the means to do that, as well as recruiting helpers and so on.

A questionnaire is essential, [2] but it must always be flexible, following their flow, always thinking of new questions, how to express them suitably, and listening. All of which Antoinet was brilliant at.

For me fieldwork is a constant discovery of how inaccurate and superficial my previous notes were. Antoinet and Frank’s enquiring spirit can be seen in these reflections that Frank later sent me:

We had no such thing as a “method”—in general we did tend to visit singers more than one time, preferably many times, in order to ask them the same questions repeatedly, and to let them sing the same songs more than once, with intervals of days, weeks, months or even years in-between. That was only possible with individual songs, of course, not with spontaneous dialogue songs, which we got acquainted with mainly in Gansu.

I think we learned most from what people told us spontaneously, about their own lives, in personal conversations, which were not strictly private conversations. People are nearly always in a space together with others. But group interviews (group chats, rather) were good, people felt at ease, they were not “attacked” by us, they were simply chatting…

Basically, in our fieldwork, we were always out to discover what we were not aware of yet. That is a hard task. And I think we kept discovering that we had not yet asked the right questions, had not investigated the right topics yet… Even now do I realize that I should go back… Maybe this is only the natural, classic, condition for fieldworkers: you return home with an idea of how things might be, you end up with an hypothesis, you suddenly stumble upon a new hypothesis which sheds new light on the situation, but then you have to go back again to test it, and the work starts all over again… A never-ending process, also because the questions you ask are nearly always bigger than the time and resources you have, and you need to address your problems piecemeal… We often wished we were five hundred people!

By the way, do watch their beautiful film Chinese shadows: the amazing world of shadow puppetry in rural northwest China (Pan, 2007).

In short, fieldwork may be an unending amount of work, but it’s endless inspiration too: and one works better when inspired. So I hope we can keep Antoinet’s spirit alive by emulating her humanity, enthusiasm, and critical intelligence.

For a recent volume on doing fieldwork in China, see here. And note the folk-song research of Qiao Jianzhong.

[1] Or for Daoist ritual, see e.g. the early fieldwork of Kenneth Dean.

[2] For her sample questionnaire for southern Jiangsu, see Chinese folk songs and folk singers, pp.395–6. Cf. McAllester’s questionnaire for the Navajo.

Li Manshan film: new version

Michele has just uploaded a new version of the film, with only tiny imperceptible changes. Spot the difference…

The main change is removing the out-take at the Temple of the God Palace (8’24” ff.).

We walked over there just after sunrise to go and record, when there wouldn’t be too much background noise. As it turned out, the cooing of birds was deafening—delightful as it was on my headphones, Michele managed to keep it under control when editing later. Li Manshan was going to do a little spoken intro recalling the temple, and since we were joined by a nice villager who also recalled the temple fondly, I thought it’d be nice to get him to stand just out of view of my camcorder so Li Manshan could have an interlocutor. It worked out fine, but their opening exchange made us all burst out laughing:

Li Manshan [confidently explaining the setup to his mate]: So we’re gonna have a natter!

[begins spiel]: In the past this Temple of the God Palace…

[Mate interrupts]: If it hadn’t been demolished, it’d be a tourist spot now!

[Li Manshan has drôle thought]: … What, you mean you demolished it?!

We tried including this exchange in the film, with a suitable pause while we composed ourselves for Take 2, but it doesn’t quite work unless you were there…

The meaninglessness of ritual

The work of Frits Staal on Indian ritual contains much from which scholars of Daoist ritual (not least I) might benefit, confronting issues that I encounter in working with Li Manshan. Staal’s ideas about orthopraxy seem to go beyond the discussions following those of James Watson for China. There’s a lot more to Staal’s work than that, but this is a start.

In “The meaninglessness of ritual”, [1] Staal eschewed “the dewy-eyed romanticism that is pernicious to any serious study of cultures and people.”

A widespread but erroneous assumption about ritual is that it consists in symbolic activities which refer to something else. It is characteristic of a ritual performance, however, that it is self-contained and self-absorbed. The performers are totally immersed in the proper execution of their complex tasks. Isolated in their sacred enclosure, they concentrate on correctness of act, recitation and chant. Their primary concern, if not obsession, is with rules. There are no symbolic meanings going through their minds when they are engaged in performing ritual.

Such absorption, by itself, does not show that ritual cannot have a symbolic meaning. However, also when we ask a brahmin explicitly why the rituals are performed, we never receive an answer which refers to symbolic activity. There are numerous different answers, such as: we do it because our ancestors did it; because we are eligible to do it; because it is good for society; because it is good; because it is our duty; because it is said to lead to immortality; because it leads to immortality. A visitor will furthermore observe that a person who has performed a Vedic ritual acquires social and religious status, which involves other benefits, some of them economic. Beyond such generalities one gets involved in individual case histories. Some boys have never been given much of a choice, and have been taught recitations and rites as a matter of fact; by the time they have mastered these, there is little else they are competent or motivated to do. Others are inspired by a spirit of competition. The majority would not be able to come up with an adequate answer to the question why they engage in ritual. But neither would I, if someone were to ask me why I am writing about it.

[…]

Most questions concerning ritual detail involve numerous complex rules, and no participant could provide an answer or elucidation with which he would himself be satisfied. Outsiders and bystanders may volunteer their ideas about religion and philosophy generally—without reference to any specific question. In most cases such people are Hindus who do not know anything about Vedic ritual. There is only one answer which the best and most reliable among the ritualists themselves give consistently and with more than average frequency: we act according to the rules because this is our tradition (parampara). The effective part of the answer seems to be: look and listen, these are our activities! To performing ritualists, rituals are to a large extent like dance, of which Isadora Duncan said: “If I could tell you what it meant there would be no point in dancing it.”

Ritual, then, is primarily activity. It is an activity governed by explicit rules. The important thing is what you do, not what you think, believe or say.

This echoes Catherine Bell’s comment that I cited in my post on Bach and Daoist ritual—for her masterly surveys of ritual studies, click here.

Here’s a trailer for Staal’s 1975 film on the Vedic fire ritual:

Poul Andersen offers caveats to Staal in a review of volumes on Shanghai Daoist ritual (Daniel Overmyer, Ethnography in China today, pp.263–83). He highlights the interpretations of the participants (including the liturgists themselves), which “in many ways influence the actual performance. They are relevant for the way in which performances take shape, develop, and are modified over time.” Such interpretations, while important, rarely offer a detailed critique, so such a view refines rather than refutes Staal’s point.

I pursue the theme under Navajo culture.

[1] Numen 26.1 (1979): 2–22. See also Ritual and mantras: rules without meaning (Motilal Banarsidass, 1996), and (source of my quote here) S.N.Balagangadhara, “Review of Staal’s Rules without meaning”, Cultural dynamics 4.1 (1991), pp.98–106.

Ask my father

*Part of my series on Irish music!*

Peter Kennedy (fiddle), Marie Slocombe, and Séamus Ennis (Uillean pipes).

Another passage from Last Night’s fun that reminds me of Chinese music is Carson’s brilliant discussion (pp.7–13) of the naming of tunes, what the Chinese call qupai 曲牌 “melodic labels”:

A: What do you call that?

B: Ask my father.

A: “Ask my father”?

I can only hope we haven’t made such a mistake in documenting folk qupai. Indeed, I could well have asked Li Manshan’s son that very question (cf. the joke at the end of our film)…

Here’s the great Séamus Ennis playing Ask my father:

This story of his bears on the subject too:

For Scottish pibroch, click here.

More early music

*Part of my series on Irish music!*

In Irish music I already cited some fine quotes from Cieran Carson’s Last night’s fun bearing on the mania for soulless competitions, including the tale of the three fiddlers. The final passage in this section is remarkable (p.98):

I find among these people commendable diligence only on musical instruments, on which they are incomparably more skilled than any nation I have seen. Their style is not, as on the British instruments to which we are accustomed, deliberate and solemn but quick and lively; nevertheless the sound is smooth and pleasant.

It is remarkable that, with such rapid fingerwork, the musical rhythm is maintained and that, by unfailingly disciplined art, the integrity of the tune is fully preserved through the ornate rhythms and the profusely intricate polyphony… They introduce and leave the rhythmic motifs so subtly, they play the tinkling sounds on the thinner strings above the sustained sounds of the thicker strings so freely, they take such secret delight and caress [the strings] so sensuously, that the greatest part of their art seems to lie in veiling it, as if “that which is concealed is bettered— art revealed is art shamed”. Thus it happens that those things which bring private and ineffable delight to people of subtle appreciation and sharp discernment, burden rather than delight the ears of those who, and in spite of looking do not see and in spite of hearing do not understand; to unwilling listeners, fastidious things appear tedious and have a confused and disordered sound.

That passage might seem like a fine description of Irish music today—but it was written in 1185, by Giraldus Cambrensis in Topographia Hiberniae!

Generally (my Daoist priests of the Li family, p.291),

I wage a tireless campaign against the Chinese scholarly trend to make ambitious links between ancient citations and living folk practice, but here is one case where I totally support it. Comparable to the centrality of the keyboard for 18th-century kapellmeisters, the sheng master was the grand director of courtly ritual music right from the Zhou dynasty around the 6th century BCE, with an unmatched understanding of scales and pitches, a custom that has persisted throughout imperial history right down to today. Of all the wise sheng masters we have met in north Chinese villages, Li Qing was among the most outstanding.

Doubtless Irish music has changed in many ways since the 12th century, and that passage is just general enough to allow us to discern parallels that may not add up to so much—but still, it’s impressive.

Transliteration

Talking of Chinese versions of foreign names, I like

- Andeli Poliwen 安德利珀利文: André Previn

- Qielibidaqi 切利比達奇 Celibidache

- Futewan’gele 福特萬格勒 Furtwängler

- Laweier 拉威尔: Ravel

- Chake Beili 查克贝里 (pronounced Charcur Bailey): Chuck Berry

- Ao Shaliwen (Ao as in “Ow!”) 奥沙利文: O’Sullivan

- Fuluoyide 弗洛伊德 is a generous expansion of Freud into four syllables.

I also like

- Dingding 丁丁: Tintin.

Not to mention the Chinese transliteration of the word toothbrush:

- tuzibulashi—“rabbits don’t shit”, which inspired me to this fine headline.

For my Chinese name, and that of Beethoven, see here.

Another Czech mate

Further to my Czech mentor Paul Kratochvil:

Along with Flann O’Brien, high on the guest list for my fantasy dinner-party would be Jaroslav Hašek—”humorist, satirist, journalist, anarchist, hoaxer, truant, rebel, vagabond, play-actor, practical joker, bohemian (and Bohemian), alcoholic, traitor to the Czech legion, Bolshevik, and bigamist”.

Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk has long been popular in China. Cecil Parrott, its English translator, also wrote a biography of Hašek’s “bottle-strewn life”, The bad Bohemian. Former British Ambassador in Prague, Parrott effortlessly avoids betraying any sympathy with Hašek’s reprobate behaviour (see also Hašek’s adventures in Soviet Tatarstan). As he explans in the introduction to his translation:

His next escapade was to found a new political party called The Party of Moderate and Peaceful Progress within the Limits of the Law […] publicly debunking the monarchy, its institutions and its social and political system. Of course it was only another hoax, designed partly to satisfy Hašek’s innate thirst for exhibitionism and partly to bolster the finances of the pub where the election meetings were held.

Among his many japes, his short-lived editorship of the journal The Animal World was curtailed after he published articles about imaginary animals.

Dangerous herds of wild Scottish collies have recently become the terror of the population in Patagonia

Thoroughbred werewolves for sale

Newly discovered fossil of an antediluvian flea

And his hobbies combined:

Everyone who votes for us will receive as a gift a small pocket aquarium.

Gratifyingly, The Good Soldier Švejk clearly appeals to Chinese sensibilities; it was translated, and the 1956–1957 Czech films were dubbed into Chinese:

Alexei Sayle wonders if the Czech regime knew what they were doing promoting Švejk, since its message hardly supports the ideals of socialist conformity. Though it became popular in many languages, I suspect there’s something about it that appeals in particular to Chinese people—an antidote to compulsory patriotism? The Chinese translator dutifully portrays it as a tirade against imperialism, but it surely spoke to The Common Man (Flann O’Brien’s “The Plain People of Ireland”) oppressed by the destructive irrationalities of a newer system…

The Chinese version of Švejk’s name (Shuaike 帅克) is perfect. It drives me to a little fantasy.

Voices and instruments

In my book (p.261) I glibly compared the Li band’s hymns to the arias in the Bach Passions, “where action and drama are suspended while we contemplate the deep meaning of a scene.” In most elite Daoist and Buddhist temples, liturgy is accompanied only by percussion, not melodic instrumental music. Many of the Li band’s hymns are sung thus, a cappella—including those used to Open Scriptures in the morning and afternoon.

Whereas Chinese studies of northern Daoist and Buddhist “music” often focus almost entirely on shengguan melodic instrumental music, in my book (ch.16) I try to put it within the ritual context. But does the shengguan accompaniment (notably the constant variations of the guanzi) express what the vocal text is unable to embody?

As usual, this is not a close parallel, but one thinks of Erbarme Dich:

“Language is not essential to this moment, or even adequate to it. A verbal penitence is expressed by the alto voice, but the violin expresses a more universal distress.” (Gardiner p. 422, citing Naomi Cumming).

But remember, I find nothing akin to word-painting in the Li band’s vocal repertoire (my book p.277):

I can find no matching of melody to textual content. There is nothing akin to word-painting, no illumination of the meaning of the text through music. Vocal liturgy is capable of arousing emotion, as for instance it should do in the Song of the Skeleton (see Yesterday…), but this is achieved through the general style of delivery rather than the specific text-setting. In musical style the Song of the Skeleton is no different from other hymns, and even its desolate text is not comprehensible when sung.

So expression is conveyed mainly through timbre. The more I listen to Li Manshan and Golden Noble, the more impressive I find the mournful nasal quality of their voices; I can sing some hymns, but can’t emulate this. They have utterly absorbed the meaning of the texts into their voices. And when the shengguan accompanies, Wu Mei complements them perfectly on guanzi, managing to combine a deeply mournful tone with an almost playful way of weaving in and out of the melodic line, ducking and diving, sometimes soaring. The singers recognize that a good guanzi player is a great help to them in rendering the text.

Anyway, both the decorations of a Daoist on guanzi and Bach’s oboe lines are spellbinding—an intrinsic part of the realization of the text. So I both demote and stress the shengguan accompaniment.

Beyond the transition of the Passions from liturgical to concert performances, the staged versions of recent years can also be compelling (for us):

And we’re already in tears (along with Peter) from the recitative of the Evangelist that introduces it. The shuowen introits of the Daoist also introduce arias…

Those of a sensitive disposition may wish to avoid reading my Textual scholarship, OMG.

Living in the past

In the mid-1980s a story did the rounds at the Central Conservatoire in Beijing, about a group of students sent to do fieldwork in a remote part of southwest China. In one village the peasants seemed not to have heard of Chairman Mao, and when asked “So who’s in charge, then?”, they hesitantly replied “Um… is it called Great Ming dynasty?” They hadn’t even heard of the Qing.

Of course this sounds apocryphal, a kind of Shangri-La story. Generally, however backward the conditions of places we visit, the scars of Maoism are evident. But I’m not sure we can dismiss it entirely…

It was formative fieldtrips like this, evoked in Liu Sola‘s 1985 novella In search of the king of singers 寻找歌王, that inspired the new generation of avant-garde composers like Qu Xiaosong, Tan Dun, and Guo Wenjing.

Reading Avedis Hadjian’s amazing book Hidden nation, I find a similar case:

The residents of an Armenian village in Sasun, in a photo taken by the photographer Shiraz during a pioneering journey in 1973. Such was their isolation that they asked Shiraz to advise “the Armenian king that there are still Armenians in Sasun.” However, the last Armenian monarch, Levon V of the Kingdom of Cilicia, had been dethroned in 1375 by Mamluk invaders.

Such stories are extreme instances of the Chinese proverb “The mountains are high, the emperor is distant“.

Hammer and Tickle

What a great title—adopted by several works on Communist humour, just as Broken down by age and sex is popular among statisticians.

Ben Lewis’s Hammer and Tickle: a history of Communism told through Communist jokes [1] has many fine jokes, like this (p.214):

The government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics has announced with great regret that, following a long illness and without regaining consciousness, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the President of the highest Soviet, Comrade Leonid Brezhnev, has resumed his governmental duties.

I’m not sure if this one is in there, but it’s had a new lease of life following Twunt’s latest rant:

A man was arrested for writing “Khrushchev is a moron” on a fence, and given 15 years in prison: 1 year for vandalism, and 14 years for disclosing state secrets.

Courtesy of Homeland, I’ve just noticed the fine metaphor for relations between the communist state and its employees:

We pretend to work, you pretend to pay us.

But Lewis is surely wrong that “For whatever reason the same phenomenon didn’t exist in the same way in South East Asia or China.” The Chinese have more such jokes than anyone, and it’s high time we had a volume of them in English: for starters, click here. One could compile a thick volume just of Li Peng jokes (preliminary offerings here and here).

Cf. More Hammer and tickle, and Big red joke book.

[1] See also e.g. Christie Davies, Political ridicule and humour under socialism.

More social commentary

This is another ever-popular story in our fieldwork joke manual:

Taking his donkey with him, a peasant goes into the county-town to do some business in the county government headquarters. Leaving the donkey in the compound courtyard, he goes in.

When he emerges he finds that the donkey has eaten up all the plants in the courtyard, so he storms up to it and bursts out,

“So you think you’re some kind of national apparatchik, eh—cadging a meal wherever you go?!”

In the original Chinese that last phrase is typically blunt and effective:

走到哪儿吃到哪儿。

Hebei: new discoveries

In the recent, ongoing, fieldwork project continuing our work on the Hebei ritual associations, led by the energetic Qi Yi 齐易, most welcome for me so far is new material on Hubenyi 虎贲驿 village (see e.g. here).

In Plucking the Winds (pp.90–92) I told how the beautiful surviving copy of the Houtu scroll of Gaoluo village was copied by Ma Xiantu, a cultured teacher and sectarian from Hubenyi village just further northeast. Then teaching in Beijing, he first borrowed the old copy of the scroll from South Gaoluo “to supplement the deficiency of my village’s Hongyang Holy Association”. His brother-in-law, South Gaoluo villager Shan Hongfu, was also staying in Beijing, and watched Ma Xiantu copying the scroll; he then bought more paper and asked Ma to make another copy for South Gaoluo. So Ma Xiantu copied it every day after school. He started copying the scroll in the 6th moon of 1942, and completed it in the 1st moon of 1943, finally adding the punctuation in red while he visited South Gaoluo to hand it over formally to the Association for the New Year’s rituals.

The 2015 fieldwork at Hubenyi, though not mentioning Ma Xiantu or the Houtu scroll, revealed further Hongyang scriptures, including an old copy of the Hunyuanjiao Hongyang zhonghua baojing 混元教弘陽中華寶經. Qi Yi and Song Yingtao 荣英涛 have collected basic data, so with bated breath I await a study from scholars of folk sectarian religion, for whom this whole area should be such a rich field… And who will supplement our work on the foshihui 佛事會 ritual associations around Yixian county?

For Hunyuan and Hongyang sects in the region, see my In Search of the folk Daoists of north China, Part Three.

An unsung local hero

I mentioned the splendid Li Jin 李金 briefly in my book (p.20):

I also made a couple of brief trips doing a reccy of Daoists in the nearby counties, assisted by my saintlike old friend Li Jin, bright young scholar Liu Yan, and feisty Driver Ma, all delightful company. No-one will ever accept any reward for all their work as my amanuensis. Elif Batuman’s fine adage about her time in Samarkand rings true: “We were either trying not to give money to people who were trying to take it, or trying to give money to people who were trying to refuse it.”

Li Jin (right), with Jiao Lizhong (centre) and driver (and polymath!) Ma Hongqi,

Hunyuan county-town 2011.

Li Jin is indeed a treasure. I only realized quite recently that he was once a celebrated performer—but it’s his infinitely generous sincerity that strikes all who meet him. In this he resembles the great Li Qing, but his story differs in that the Li family Daoists always strived to keep under the radar, maintaining their independence from official control, whereas Li Jin’s life has been shaped more directly by the vicissitudes of the Party. In many ways his story is unexceptional, but while my accounts of Yanggao generally concern folk more than state, [1] it reminds us of the presence of the latter—and the presence of Good People within it.

A year older than Li Manshan (but not related to the Li family Daoists), Li Jin was born in 1945 in the poor village of East Shahe just southwest of Tianzhen county-town. He had two older brothers, and at first his family thought to give him away to a close friend, a childless local doctor, but in the end they kept him. Their grandfather was the patriarch. He had gradually accumulated over 30 mou of land, and with the three brothers helping in the fields, their life was quite comfortable until “Liberation”. In the land reform of 1947–48 they were classified as middle peasants (cf. my book pp.95–9); in the 1964 Four Cleanups campaign they were stigmatized as “rich peasants”, and only rehabilitated in 1982—not unlike the Li family Daoists.

When a basic primary school system was established, Li Jin went to school in the converted Dragon King temple. He recalls the fine opera stage opposite it, where an opera troupe would perform for the gods on the 18th of the 6th moon. The stage remained intact—young Li Jin himself remembers performing the item “Playing the flower drum” (Da huagu 打花鼓) there when he was 10 sui.

By the time he graduated from six years of primary school he was a favourite of the teacher. He became prominent in school performances; what he calls his “silly look” was popular. In 1959 he passed the exam to enter secondary school in Tianzhen county-town—no easy feat. It was life-changing for him. On his very first day there, he was thrilled by the flag-raising ceremony in the school’s huge exercise ground. He began learning Russian enthusiastically, dreaming of becoming a translator. But he was soon chosen to do an audition in Yanggao county for a new state-run troupe that was to perform the popular skittish local duet “little opera” errentai.

So in the 2nd moon of 1960, when only 16 sui, he was chosen to join the new county folk opera troupe (Yanggao xianzhi p.468). This, indeed, was soon after Li Qing was chosen for the regional arts-work troupe in Datong (my book pp.113–118), and at the height of the famine.

Later Li Jin heard that he had nearly got the county mayor into trouble. None other than Jing Ziru, head of the Bureau of Culture and the (only) brilliant local historian of Yanggao (my book p.50), told him that at his audition, the mayor had taken exception to his two “wolf-teeth”, but the others pointed out they could be taken out—indeed, in 1962 he had them extracted by a quack dentist while they were performing in Zuoyun county. Rather him than me.

Li Jin soon went on to become a celebrated performer. The troupe’s expenses were to be footed by all the people’s communes in the county, so it was ponderously named Shanxi sheng Yanggao xian renmin gongshe lianshe minjian gejutuan 阳高县人民公社联社民间歌舞团. If there was a sign at the gate of the compound, it must have collapsed under the weight of its own lettering…

Li Jin remembers those early days in the troupe fondly, with its twelve performers and six musicians. Of course it was a terribly tough time, but the troupe was doing well, and led a somewhat less tenuous existence than the common folk, “like being in kindergarten”. Still, he only earned 18 kuai a month.

The leadership praised their first hastily-rehearsed programmes of Da jinqian 打金钱, Zou xikou 走西口, Gua hongdeng 挂红灯, and Gusao tiaocai 姑嫂挑菜. At first Li Jin was chosen to specialize in the handsome sheng roles, but with his “silly look” he found it too much of a challenge, and he soon gravitated to the chou clown role.

The character is meant to make people laugh, but once he made himself corpse. Playing the role of a clown county official, one day he got the words wrong and couldn’t help bursting out laughing. The troupe leaders gave him a kicking backstage but he still couldn’t stop laughing. At the next meeting he was criticized and his 3 mao supplement for the day was withheld. This is the kind of story that musos delight in.

They were on tour all year round. I was surprised to learn that tickets were for sale—so they had to try and control villagers without tickets trying to sneak a look, no simple task.

Following the mood of the times, the troupe soon began performing modern items instead of their original classical stories, so Li Jin’s clown roles were now mainly “negative” characters like spies or traitors, not the more sympathetic (or at least neutral) roles of old. Despite the troupe’s popularity with audiences, and Li Jin’s own reputation, in the Lesser Four Cleanups campaign of 1963 they were banished to the countryside for “tempering through manual labour” (laodong duanlian). As the campaign intensified, they were active in Tianzhen county as a Four Cleanups work troupe. At first Li Jin was excluded from taking part in such “battle teams” (zhandoudui) by his bad class background, but soon the order came down that everyone had to join in, so for the next two years he was part of a group of a dozen or so “Red Flag warriors”.

By 1967 a new directive descended on them, warning them that their performances since the formation of the troupe, glorifying “ox demons and snake spirits, scholars and beauties”, contradicted the agenda of the Party. The leadership decided to amalgamate the troupe with the county’s other opera troupe (for the classical opera Jinju), at the same time reducing the personnel. By 1968 even this new combined troupe was abolished. Li Jin was assigned to work as a cook. His wife was sent to work in a troupe in Xinzhou, rather far south—so even his family was being broken up. He’s grateful that she managed to return after some time.

In 1970 the county established a Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team. All the recruits had to do was to be able to hum a few phrases and not be too ugly, and they were in. But the authorities soon realized the standard wouldn’t do, and had recourse to the disgraced former troupe members. So Li Jin now found himself taking part in simple cheerleading performances, trapped in “a bottleneck of monotony”. But they did raise standards, and their performances enjoyed a certain popularity.

The scene changed quickly from 1976, with more traditional genres regaining a position among modern styles. In 1979 the county “folk opera troupe” (minjian gejutuan, later called Errentai jutuan) was restored, with both new and old styles reflected. Supported by the county leadership, their reputation again spread. Li Jin, still only in his mid-30s, got back to work conscientiously, going on to become Director of the troupe. In 1988, as “popular voting” came into vogue, he stepped down after a close-fought election.

In 1989 he moved to the county Bureau of Culture, a radical change in work style—and a challenge upon which he embarked with typical enthusiasm. He was glad to broaden his experience of local culture. Since then, privately-run errentai groups have bloomed in the countryside, taking a major role at weddings and funerals. I don’t suppose Li Jin is always impressed by the pop style that now dominates there, but he is proud of playing a role in the recognition of the Li family Daoists and the Hua family shawm band in the Intangible Cultural Heritage roster. Despite my reservations about the ICH, I can appreciate his satisfaction.

In a climate since the 1990s whereby most cadres seem to spend their time staggering around pissed from one state-funded banquet to the next, [2] Li Jin seemed to be the only one who ever got any real work done. And he at once understood that I was there to work too, inconspicuously doing all he could to help me—like biking through the snow to convey an obscure foreign message on my first trip.

In recent years, while staying with Li Manshan and following him round funerals, I make occasional visits back to the town for a shower and a nice quiet informal meal with Li Jin. Since his retirement, though not in great health, he has returned to his beloved errentai, taking place in regular amateur meetings.

He is affable and generous with everyone, and accepts people (even me) as he finds them—embodying the noble virtues that the system often trampled on. He has always believed in humanity, social justice, and the aims of the Party.

* * *

This is the kind of life that books like those of Dikötter, single-mindedly focused on tragedy, cannot reflect. Whereas the more focused ethnography of Friedman, Pickowicz, and Selden is also unflinching, it is based on fieldwork, and so can’t help showing a certain empathy. But more general trawls through the archives like those of Dikötter can only be partial, another kind of propaganda. One can hardly challenge his details—indeed, the tragedy lies precisely in the way that sincerity was repressed, and it does need documenting—but one needs a more nuanced, perspective.

My account may make Li Jin sound a little like one of those selfless cadres of yore, by contrast with the self-serving crew that holds sway today. But there really were, and are, people like that… See also Yanggao personalities.

There is nothing like a quiet chat over a simple bowl of noodles with Li Manshan and Li Jin.

[1] In my 2004 book on the Gaoluo ritual association, one finds a closer relationship between folk consciousness and local cadres.

[2] Though in my book (p.314) I note recent sumptuary laws, and a jolly good thing too.

Copyright

On street corners in Beijing in the early 1990s a wealth of pirate DVDs of foreign films were being sold, not always very surreptitiously. Expats were happy to snap them up—referring to the exercise as “investigating the infringement of international copyright law”.

Solfeggio

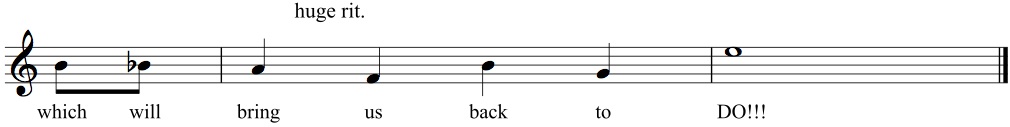

An aspiring singer on a TV talent show decided to perform Doh a deer, and rashly decided to go out, too literally, on a high note:

Which reminds me—the traditional gongche notation for the melodic skeleton of ritual shengguan ensemble translates nicely into solfeggio (and indeed into modern Chinese cipher notation)…

Da Zouma score, written for me by Li Qing, 1992 (playlist #4, commentary here).

“But that’s not important right now”. I allude, of course, to Airplane:

The Chinese gongche system, like those of Europe and India, is heptatonic:

cipher notation: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

solfeggio: do re mi fa so la si

Indian sargam: Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni

gongche: he si yi shang che gong fan,

with liu and wu as upper octave notes for he/do and si/re respectively (taking the older system with he, rather than shang, as do! Call Me Old-fashioned).

For those who can’t fathom the British propensity for punning, the only line of Doh a Deer that makes any sense is La, a note to follow so—precisely the only line where the author reveals a touching fallibility. Such literal audiences would be happier if it were all like that:

…

Re, a note to follow do

Mi, a note to follow re

Fa, a note to follow mi

and so on…

It only remains to overhaul the opening line. The original version “La, a note to follow so—if you’re moving upwards in conjunct motion that is” was overruled as too pedantic, of course.

Another fun exercise is to sing the phrases in reverse order, descending instead of ascending from Doh:

Doh, a deer…

Ti, a drink with jam and bread

La, a note to follow ti!

So, a needle pulling thread

etc.

Given how well we know the song, it seems a bit weird how crap we Brits are at solfeggio. Another fun game would be to try singing the whole thing only in solfeggio:

Do, re mi, do mi do mi,

Re, mi fafa mire fa

and so on.

Then we can use the tune to familiarise ourselves with Indian and Chinese solfeggio:

Sa, Re Ga, Sa Ga Sa Ga,

Re, Ga MaMa GaRe Ma…

he, si yi, he yi he yi,

si, yi shangshang yisi shang…

We can also sing the song to the many scales of Indian raga in turn, with their varying flat or sharp pitches (note my series, introduced here)—a simple example: in rāg Yaman, try singing a sharp fourth for fa, a long long way to run…

Alas, a fascinating medley of versions in French, German, Italian, Spanish (x3), Japanese, and Persian has just disappeared from YouTube. Let me know if you find it!

For a brilliant pun on the Mary Poppins song, see here. And for “do, a note to follow mi“, click here.

Breaking news (not)

Old headline from The China Daily:

And more recently:

Fiendish, these orientals…

Laozi

Household Daoists tend to know about performance, not doctrine. I focus on practical knowledge—right down to which cymbal patterns to use as interludes for which hymns, and when to use them, or not. What the Li family don’t know, or do, is things like secret cosmic visualizations.

They don’t necessarily know how to write the texts, or if they do so (for me) they may write some characters a bit approximately because they already know how to recite them.

They know nothing of Laozi’s Daode jing, so central to Western images of Daoism. When I quote the pithy, nay gnomic, opening two lines to Li Manshan and his son Li Bin:

道可道非常道 The way you can follow is not the eternal way;

名可名非常名 The name you can name is not the eternal name.

they don’t quite get it, and I have to translate it into colloquial Chinese for them! Hmm…

We have a bit of fun playing with feichang, which in modern Chinese is “very”, rather than the classical “not eternal”. Actually, in their local dialect they don’t use feichang at all, though of course they know it. In Yanggao the usual way of saying “very” is just ke 可, pronounced ka—thus “dao kedao feichang dao” might seem to be “The way is soooo waylike, I mean it’s just amazingly waylike”…

Still, Daoists like Li Manshan will have picked up a broad understanding of the texts they sing every day, even if they have never been taught their “meaning”. They know Laozi not as the author of the Daode jing but as a god.

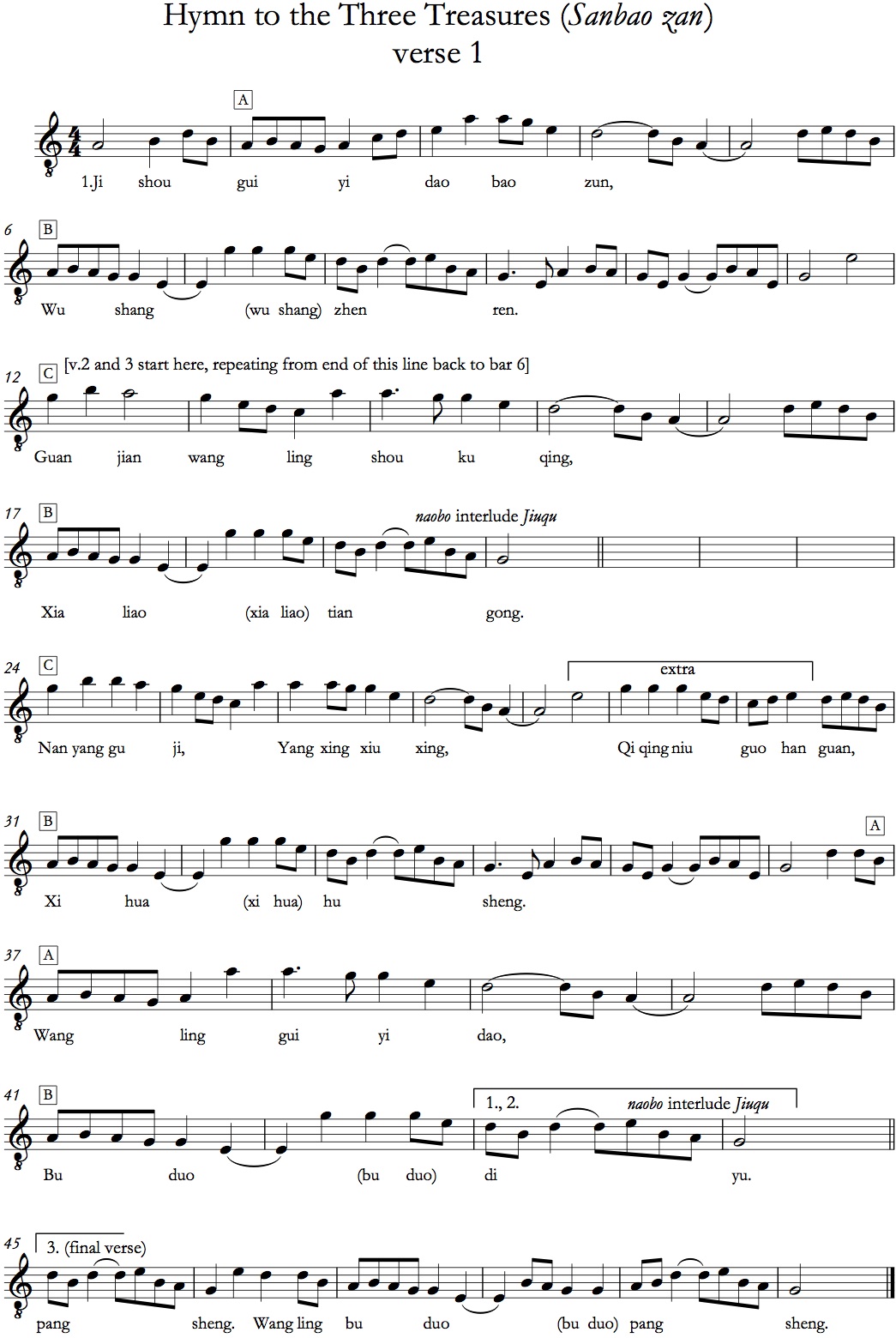

As I wrestled with translating the Hymn to the Three Treasures (Sanbao zan), used for Opening Scriptures in the morning (Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.262–3, and film from 22.01), Li Manshan explained it to me.

Hymn to the Three Treasures, from Li Qing’s hymn volume, 1980.

The subject of the first verse to the dao, “We bow in homage to the worthy of the dao treasure, Perfected One without Superior” (Jishou guiyi daobaozun, Wushang zhenren) is Laozi himself, so it is he who is the subject of the remainder of the verse: “He descended from the heavenly palace” (xialiao tiangong) refers to Laozi descending from the heavenly palace after beholding the sufferings of the deceased spirit (guanjian wangling shou kuqing)—it’s all about Laozi! So you see, Li Manshan does get the texts…

As for any ritual tradition, where does the “meaning” reside, when texts are unintelligible to their audience? When we translate and explain ritual texts, we are radically altering them as experienced by their audience. True, the performers, the priests, certainly “understand” them, to various degrees, if not in the same way as scholars translating them. I don’t suggest limiting ourselves to the consideration of how people experience rituals, but that should surely be a major part of our studies. Experience lies beyond textual exegesis, consisting largely in sound and vision.

I am reminded of Byron Rogers on an American version of the New Testament (Me: the authorized biography, p.268):

Pilate: “You the King of the Jews?”

“You said it.” said Christ.

There’s another one for the Matthew Passion (cf. Textual scholarship, OMG). “What is truth?”, indeed…

Mercifully, there is no movement to translate the ancient texts of Daoist ritual into colloquial modern Chinese. Of course, for northern Daoist ritual a modern translation wouldn’t make the texts any more intelligible anyway, given the slow tempo and melisma.

Laozi does appear in one of our favourite couplets for the scripture hall (see Recopying ritual manuals, under “The couplet volume”; cf. my book pp.194–5—not easily translated!):

穩如太山盤腿座 Seated in lotus posture firm as Mount Tai,

貫定乾坤李老君 Old Lord Li thoroughly resolves male and female aspects.

For a basic roundup of posts on the Li family Daoists, see here.

Organology

Quaint and not entirely useless fact:

The names of indigenous and ancient Chinese musical instruments usually consist of one single character, like

qin 琴 zither

sheng 笙 mouth-organ

zheng 箏 zither

di 笛 flute,

whereas those imported from outside China (generally Central Asia) tend to have two characters, like

bili 篳篥 oboe (Japanese hichiriki; descendant of the Chinese guan[zi] 管子)

pipa 琵琶 lute

erhu 二胡 fiddle (and indeed huqin 胡琴, tiqin 提琴, and so on)

suona 嗩吶 shawm

yangqin 揚琴 dulcimer.

“Not a lot of people know that”. Perhaps we can think of some exceptions?

By the way, the pipa was held horizontally in medieval times, the angle getting higher over the course of a thousand years until attaining its present vertical position—surely the longest and most gradual erection known to mankind.

Lower row, left: Yang Dajun.

There are still a couple of regions where the older more horizontal position has been maintained:

(left) nanyin in Fujian; (right) Shaanbei bard.

Tone of voice, and audiences

Around 1975, while “studying” at Cambridge, I somehow managed to get an invitation to tea with Sir Harold Bailey (see also here), eminent scholar of ancient Central Asian philology. I guess it was Laurence Picken, or Denis Twitchett, who made the introduction.

Sitting me down at his side, Sir Harold at once embarked on a lengthy discourse about medieval Khotanese texts, peering at a jumble of manuscripts on the desk before us. His only companion was his cat, whom he also addressed periodically, without modifying either his gaze or his measured academic tone.

“Here I found a clear clue to a syntactical link with the Sogdian manuscripts that had been excavated some time before… And I suppose you want another saucerful of milk.”

Before I could assure him that I was fine with my cup of tea, he went on,

“It may take some time to map the linguistic links between the various medieval oasis towns… It’s no use rubbing up against my legs like that, you’re not going out into the garden again, we can’t have you bringing in any more birds…”

It took me some time to get the hang of this.

From his obituary:

A task now facing Bailey’s colleagues is the elucidation of his rhyming diaries. When told at our last meeting that the course of a lifetime had transformed these into an epic of over 3,000 verses in a private language concocted from classical Sarmatian inscriptions, I asked Bailey why he was so fond of obscurity. “Well, the diaries are not really so obscure,” he said. “Indeed I’d say there’s hardly a line that could not have been understood by any Persian of the fourth century.”

For another story about context sensitivity, see here. And do read Compton Mackenzie meets Henry James!

Terylene

In ch.18 of my book (p.342) I reflect on the Li band’s recent concert tours and Intangible Cultural Heritage status:

All this may sound like a typical story of adaptation to modern secular contexts. But it’s not. Let’s face it, the Li family is never going to become the next Buena Vista Social Club. Year in, year out, their livelihood remains performing for local rituals. Li Manshan’s recent nomination as Transmitter of the ICH brings him a modest extra income for now, but the Daoists continue to rely on doing funerals around their home base; their ICH status and foreign tours are only a minor element in their reputation, which is an accumulation of local charisma over many generations. They still lack disciples, either from their own or other families; and crucially, local patrons no longer pay much attention to the niceties of ritual practice.

It all reminds me of the elderly fiddle player in the Romanian village band Taraf de Haidouks, reflecting on his meteoric rise to global success on the world music scene:

A little fairy granted me my wish to be happy in old age. Now I have suits in terylene.

For more on adapting Daoist ritual for the concert stage, click here. For a populist fantasy, see Strictly north Chinese Daoist ritual. See also World music abolished!!! For Paris as pedagogical Mecca, see Nadia Boulanger, and Kristofer Schipper.

Muzak

Ethnomusicologists, aspiring to some pseudo-scientific objectivity, tend to put their tastes on hold—for like John Cleese in the cheeseshop sketch, we “delight in all manifestations of the Terpsichorean muse”.

The live version is also very fine:

Football songs, Bulgarian wedding laments, ice-cream-van jingles, Demis Roussos, world accordion conventions, even Beethoven, all are grist to our mill.

My esteemed colleague Helen Rees, in a fine outline of the Chinese soundscape, wrote:

Doorbells play Muzak when pressed.

I like that—I play Muzak when pressed too. For more on the doorbell, press here.

And here‘s a sequel on ice-cream vans and garbage trucks!

In memory of Paul Kratochvil

Wedding party, Cambridge 1976.

At Cambridge during the Cultural Revolution, immersed as I was in the Tang dynasty, my only clues to the funkiness of contemporary Chinese culture came from my teacher the fine linguist Paul Kratochvil (a surname that suitably means “fun”). Born in 1933, he had somehow became an expert on the phonetics of modern Chinese, fleeing Czechoslovakia in 1968 to take up a post at Cambridge with the help of the Oxford sinologist Piet van der Loon. He features in this impressive introduction to Prague sinologists (for whom, see here).

Recommending to me a book called Current Trends in Linguistics, Paul looked bemused when I asked him what I should look it up in the library under—like an editor’s name or something:

“Well, Steve, try ‘C’—if that doesn’t work, I guess you could try ‘K’…”

While he was still in Prague, a friend in China addressed the envelope of a letter to him with great economy:

(“Czechoslovakia, Comrade Paul”). Sure enough, he received it.

Over copious beer in the pub where he used to take me for what were euphemistically described as “supervisions”, Paul recalled this story:

While still in Czechoslovakia he had served as interpreter for the Czech army, and at one high-level conference in Prague receiving a Chinese military delegation, he found himself interpreting for a Czech general at one end of the table and a Chinese general at the other.

The talks had gone well, and the Czech general was winding up with the customary sonorous platitudes.

“I hope both sides will be able to exchange experiences!” he declared majestically.

My friend Paul was already a fine linguist, and he knew there were some binomes in Chinese which you could say in the order either A-B or B-A, but alas he thought jingyan, “experience”, was one of these. So he blithely translated, “Wo xiwang shuangfang nenggou jiaohuan yanjing”, which unfortunately comes out only as

“I hope both sides will be able to exchange spectacles.”

This puts the Chinese general in a spot; the TV cameras are trained on him, and he mustn’t make a faux pas. Can this be some weird Czech custom denoting fraternal solidarity? As luck would have it, both generals are wearing spectacles. The Chinese general hesitantly takes off his glasses and holds them out over the table towards his Czech counterpart.

This, of course, presents no less of a challenge for the Czech general; having said nothing at all about spectacles, he is mystified to see this Chinese geezer holding out his spectacles across the table, and he too has to think quickly. Can this be some ancient Confucian ritual denoting fraternal solidarity? He too hesitantly takes off his glasses and offers them across the table.

My chastened mentor later switched on the Prague TV news to see a report, the newsreader announcing solemnly, “And at the end of the conference the two sides exchanged spectacles in the ancient Chinese gesture of comradeship”—as the two generals groped their way to the door.

For a suitable fanfare for the event, see here. Among several more fine stories from Paul, I like this, and indeed this. See also Czech stories: a roundup.

The north-south divide

One of the big themes of my work is what a raw deal folk Daoism in north China gets.

Confession

I truly believe that one day there will be a telephone in every town in America—Alexander Graham Bell

The date of the first landline phone in Li Manshan’s village is another of our standing jokes.

This is really embarrassing to admit, but when I asked him about it in 2011, I heard his reply as ‘sisannian’, so I unquestioningly wrote ‘1943’ in my notebook, I mean how mindless was that of me… Only later, writing up my notes back home, did I smell a rat, and it finally dawned on me that he must have said shisannian (qian), ‘thirteen years ago’! (The difficulty of distinguishing shi and si was only part of my howler; and actually, he would never say sisannian for 1943—even if he knew such a date he could only say “32nd year of the Republican era”, cf.my book pp.37-8). So the first landline was only installed in 1998, just a few years before mobile phones swept the board.

Now, whenever we misunderstand each other, we just say “sisannian” and fall about laughing. For more on our relationship, see here; and for a classic joke, here. For early linguistic escapades in Hebei, see here.

The percussion prelude

In my book (p.280) I observed a subtlety of Yanggao Daoist ritual that may elude us:

Novices soon pick up the short pattern in rhythmic unison on drum, small cymbals and yunluo that opens and closes every item of liturgy, an accelerando followed by three beats ending with a damped sound. This is known as luopu (“cadential pattern”) and it turns out that the number of beats is fixed, 7 plus 4—unless the guanzi player needs a bit more time to prepare his reed!

See also Tambourin chinois, and Drum patterns of Yanggao ritual .

Much less impressive is Beethoven’s take on this, the four soft quarter-note beats that open his violin concerto (less creative than the EastEnders Doof Doof). The quote from my book is itself just a prelude to the popular story of a famous conductor rehearsing his orchestra in the concerto. Though he was notorious for nit-picking, one might suppose that at least here the band would get up a bit of a head of steam before he started correcting them. But no, sure enough he brings them to a halt even before the oboe can come in.

Turning to the bemused timpanist, he says,

“Can you play that with a little more… magic?”

The timpanist looks back at him sullenly, beats out the four notes again, and goes,

“Abra-ca-fucking-dabra”.

* * *

In Daoist ritual there’s nothing quite akin to “rehearsal”, but during a ritual Li Manshan maintains standards by the subtlest of facial gestures, with a little glare if the ensemble is less than perfect. As I learn, I benefit from such hints.

A meeting with Teacher Wang

With Li Manshan in Hong Kong, 2011

Chinese peasants tend to “eat” cigarettes (chiyan) rather than the standard “take a drag on” them (chouyan)—yet another instance of the practical blunt charm of their language.

Timothy Mo alludes to this locution in Sour Sweet:

“Eat things, eat things,” he said aloud, gesturing to the smoking plates in front of everyone but only lighting a cigarette for himself.

“You don’t eat things yourself, Grandpa?” This was Mui.

“I eat smoke,” he quipped, laughing immoderately at his own wit.

Indeed, the expression survives from 17th-century usage, as shown by Timothy Brook in Vermeer’s hat.

At a conference in Hong Kong (my book pp.333–4) I was delighted to introduce Li Manshan to the illustrious Taiwanese scholar C.K. Wang. Apart from his indefatigable energy in opening up the vast field of ritual studies in mainland China, he has a remarkable gift for finding a place for a surreptitious smoke (cf. the first poem in Homage to Tang poetry). In Hong Kong, where smoking laws are draconian, he would regularly lead us through labyrinthine corridors to some corner of an underground car park for a furtive fag.

This soon became part of my secret language with Li Manshan. Back in Yanggao, he was careful not to smoke in the presence of his baby grandson—so sometimes when I felt he needed a fag-break, I would suggest to him, “Shall we go and hold a meeting with Teacher Wang?”

For Li Manshan and Andy Capp, click here.

Fun with anachronisms

And the roar of Moses’ Triumph is heard in the hills

Without even knowing how I feel about the White Cloud Temple in Beijing, my adorable cat Kali (R.I.P.) threw up over my copy of the Jade Pivot Scripture, which I had bought in an edition printed at the temple.

One ritual title that features only fleetingly in the ritual manuals of the Li family Daoists in north Shanxi is Thunder Lord of Three-Five Chariot of Fire (Sanwu huoche leigong). This is among the attributes of the deity Wang Lingguan, and a trace of the thunder rituals of Divine Empyrean Daoism. [1] In the Li family manuals it appears only in the Mantra to Lingguan and in the Xijing zayi manual, no longer performed and thus no longer familiar to them: [2]

From Xijing zayi manual (Sanwu huoche Lingguan on line 3), copied by Li Qing

So my excuse to discuss it here is flimsy as ever, but we all need a bit of light relief every so often. This also relates tenuously to my comments on hearing Bach with modern ears.

Huoche “chariot of fire” (glossed as “fireball”) may prompt titters at the back, since in common modern parlance it means “train”. Whereas “And the roar of Moses’ Triumph is heard in the hills” is a translation that has been inadvertently amusing only since the spread of the automobile [mental note: must get that exhaust fixed], [3] huoche is an ancient original which could have been affording chuckles to Daoist scholars since the term became common usage for “train” in the late 19th century. When you’re immersing yourself in the abstruse mysteries of the Daoist Canon, you have to take such diversion where you can find it.

What’s more, we may giggle impertinently at another of Lingguan’s attributes, Sanwu (Three-Five)—erstwhile a brand of cigarette that Chinese people associate with Englishness (much to my perplexity, since I’ve never heard of them outside China) just as much as London fog. (For “the smoking substances of non-nationals”, see More from Myles).

So here we appear to find Lingguan smoking a posh foreign cigarette on a train journey through his spiritual domain—being a high-ranking Daoist cadre, he would get to travel soft-sleeper (cf. Fieldwork and textual exegesis).

[1] The appellation may commonly be found in the Daoist Canon, but, more relevant to “texts in general circulation” (my book pp.218–24) and the practices of the Li family may be its appearances in Xuanmen risong: Xuanmen risong zaowan gongke jingzhu 玄門日誦早晚功課經注, chief editor Min Zhiting (Beijing: Zongjiao wenhua chubanshe, 2000), pp. 166–7, 244–5. See also Rethinking Zhengyi and Quanzhen.

[2] My Daoist priests of the Li family, p.376, cf. p.381; for the Divine Empyrean, see also pp.219–20.

[3] A substantial irreverent online industry in such Biblical quotes has arisen.

Fantasy Daoist ritual

The Pardon ritual led by Li Qing (2nd from left), Yanggao 1991 (my film, from 48.34).

As a change from my literary party game, here’s an arcane spinoff from the game of picking a fantasy world football team, or chamber orchestra.

Let’s choose our all-time most amazing group of Daoist ritual specialists, including both liturgists and instrumentalists. Of course, the list of candidates is endless, so I’d seek to refine the search by selecting those known mainly for their ritual performance, rather than for compiling vast compendia of manuals.

Thus the list could include early luminaries like Kou Qianzhi 寇謙之 (365–448) (who might speak a dialect similar to that of Li Qing, except that they lived over 1500 years apart), Tao Hongjing 陶弘景 (456–536), and Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850–933) (see their entries under Fabrizio Pregadio ed., Encyclopaedia of Taoism).

Churlishly fast-forwarding a millenium, among modern Daoists we could include Chen Rongsheng 陳榮盛 (1927–2014) from Tainan, [1] Zhang Minggui 張明貴 (1931–2016) of the White Cloud Temple in Shaanbei, and our very own Li Qing 李清 (1926–99); among a host of great drum masters one might recruit An Laixu 安来緖 (1895–1977) from Xi’an and Zhou Zufu 周祖馥 (1915–97) from Suzhou.

Above: left, Kou Qianzhi; right, Tao Hongjing;

below: left, Zhang Minggui; right, An Laixu.

For once, we can leave historical change to one side: it remains to be seen how effective Pelé and Messi would be together as a forward line-up, or Saint Cecilia and Bach (in the orchestra, or indeed in the football team; cf. the Monty Python Philosophers’ football). A more basic difference is that—more than football or the WAM canon—the performance of Daoist ritual is always specific to a small locality. Even if their ritual manuals may have a lot in common, household Daoists from different places can hardly work together. Never mind Daoists from Shanghai, Fujian, and Hunan; even within north Shanxi, the whole ritual performance of the Li family in Yanggao is significantly different from that of groups in Hunyuan or Shuozhou counties very nearby.

Fun game, though. See also Strictly north Shanxi Daoist ritual.

Chen Rongsheng.

[1] Until quite recently, much of our knowledge of modern Daoist ritual (despite its great diversity) was based on the tradition of Chen Rongsheng, meticulously documented by Kristofer Schipper and John Lagerwey. Here’s a tribute, with precious clips of Master Chen’s ritual practice:

Links to lengthier ritual sequences here. Alas, Michael Saso’s early clips of his Master Chuang no longer seem to be in the public domain.

Funeral music

Beijing concert, 2013.

On the Li family Daoists’ 2013 tour of Germany I suggested an extra item in our evolving concert programme, an a cappella sequence based on the Invitation ritual performed at the edge of the village (my book p.339; film, from 58.14; playlist #1, with commentary here).

At first they were reluctant: while they have no qualms about performing ritual items on stage, they worried that performing an item so explicitly funerary might be unsuitable. I pointed out that some of the greatest music in the concert tradition of Western Art Music is for the dead.

Apart from various requiems (Mozart, Brahms…), one of the pieces I used to reassure them that funeral music was quite familiar to Western audiences was Buxtehude’s Klaglied. Though a recording by the wondrous Michael Chance has just disappeared from YouTube (BRING IT BACK AT ONCE!!!), Andreas Scholl’s version is also great:

Not that the Daoists were remotely impressed by it—by contrast with Steven Feld’s influential experiments in finding which kinds of alien musics might strike a chord among the Kaluli (Sound and sentiment). They enjoyed our trip to the Bach museum in Leipzig not so much for the music as to get a glimpse of the life of a European ritual specialist; and when I showed them the EBS video of the Christmas oratorio they were mainly amused to see me in tails. I can’t even turn them on to jazz.

Occasionally some well-meaning urbanites have rashly suggested I bring my violin to play along with the Daoists, or even arrange their music for orchestra—but to their credit, the Li band have the taste never to do so.

Anyway, the Invitation has turned out to be a great success in our touring programme, a moving tranquil interlude between the uproar of “catching the tiger” and the wild percussion of Yellow Dragon Thrice Transforms its body. As an encore for our French tour in 2017 we even sang the Mantra to the Three Generations (playlist #2 and #3), which follows the Invitation at the gateway after the return to the soul hall.

For adaptations of ritual to the concert stage, see also here, under “The reform era”.

Proof-reading

Another highlight from The China Daily was a full-page advertisement taken out in 1987 by the wackily-named China National Arts and Crafts Import and Export Corporation Guangdong branch. The detailed report on the fine products on offer to a discerning international clientele should have been headed, simply,

Guangdong Arts and Crafts

But when they sent it for checking, the English proof-reader found one phrase of the text less than elegant, circled it, and, in an empty space—unfortunately just to the right of the caption—wrote “an awful cliché”. Sure enough, the headline came out:

Guangdong Arts and Crafts an awful cliché

I trust this will lead you to explore my roundup of wacky headlines. See also my series of homages to Myles’s Catechism of cliché:

Chinese clichés

Chinese music clichés

Chinese art clichés

Tibetan clichés

Orchestral clichés

Mindsets

True story:

Applicants for the post of principal conductor of the LA Phil were asked to submit a list of works they’d like to conduct in their first season. Esa-Pekka Salonen’s list was full of pieces by challenging contemporary composers. At the interview, the chair of the board looked severely over his application, turned to him and said,

“I don’t quite know how to put this to you, Mr Salonen, but… here at the Phil, we prefer our composers… dead.”

This may still apply to a considerable extent within the echelons of WAM; yet ironically, when those dead composers were alive, the core repertoire was contemporary: baroque and romantic audiences came along expecting to hear new music.

For China too, as I show in Appendix 1 of my book Daoist priests of the Li family, I attempt not a normative reconstruction of some timeless ancient wisdom, but a descriptive account of ritual life within changing modern society. See Debunking “living fossils”.

For the great maestro Salonen, see also here and here. For more interview stories, click here.

Surprise

In this photo, the woman on the far left is often claimed to be Mozart’s widow Constanze (1762–1842), just imagine (see here)… Or is it? For doubts, see wiki.

Many would like to believe it. If it is her, then it will be one of the most surprising things you will ever see. OK, it was taken in 1840, when Wolfgang was long gone. Few wives outlived their husbands. Given the harshness of the times, she hardly looks 78.

As Sean Munger comments, Constanze became the Yoko Ono of the 19th century. Wiki also cites the Grove dictionary:

Early 20th-century scholarship severely criticized her as unintelligent, unmusical and even unfaithful, and as a neglectful and unworthy wife to Mozart. Such assessments (still current) were based on no good evidence, were tainted with anti-feminism and were probably wrong on all counts.

* * *

If only we had photos of the Li family Daoists (and their wives) from the late imperial era… Even the photo of Li Peisen and his wife from the 1940s is rare enough. Indeed, in a world where female members of a family are taken for granted at best, people remembered her as exceptionally able and intelligent too.

Lost in translation

Two gems I found on a room service menu in Beijing, 2015:

Fuck to fry the cow

Discredited mandarin fish of Mount Huang

Translations on menus provide rich entertainment, of course. For East Asia, Victor Mair gets to grips with some on languagelog (some links here), and that site has many more Silly signs. See also my Temple Chinglish.

For a menu pun, I’m most taken by this—as if inviting a Chinese franchise of Flann O’Brien:

which indeed leads nicely into Lyrics for theme tunes…

5’20”

Of all the beautiful things you can do in 5 minutes and 20 seconds (like playing Yellow Dragon Thrice Transforms its Body at the end of the Transferring Offerings ritual), the divine Ronnie’s 1997 maximum is likely to remain unmatched in human history:

Beats 4’33” any day, with all due respect to John Cage.

I shouldn’t need an excuse for showing this, but here it is. After taking Li Manshan to a conference in Hong Kong (my book, p.333), I was staying with him in a posh hotel in Beijing when we switched on the TV to find Ronnie playing in the world masters snooker. Snooker has become staggeringly popular in China, but Li Manshan hadn’t seen it before, and his amazement was delightful. So I showed him this 147, which is flabbergasting even if you don’t quite know how ridiculously difficult it is…

After the lavish banquets in Hong Kong, at which we both felt rather uncomfortable, we were happy to eat a simple bowl of noodles in peace together in a little caff over the road. Next day I took him to the station to take the train home and get on with his routine of determining the date, decorating coffins, and funerals.

My favourite expression of snooker commentators is “he’s eying up a plant” (see here, and here). Tang poetry is all very well, but I wonder how you say that in Chinese…

Since Ronnie is often described as the Mozart of snooker, I note that Mozart enjoyed a game of billiards.

For more on Ronnie and snooker, see this roundup.

Homage to Tang poetry