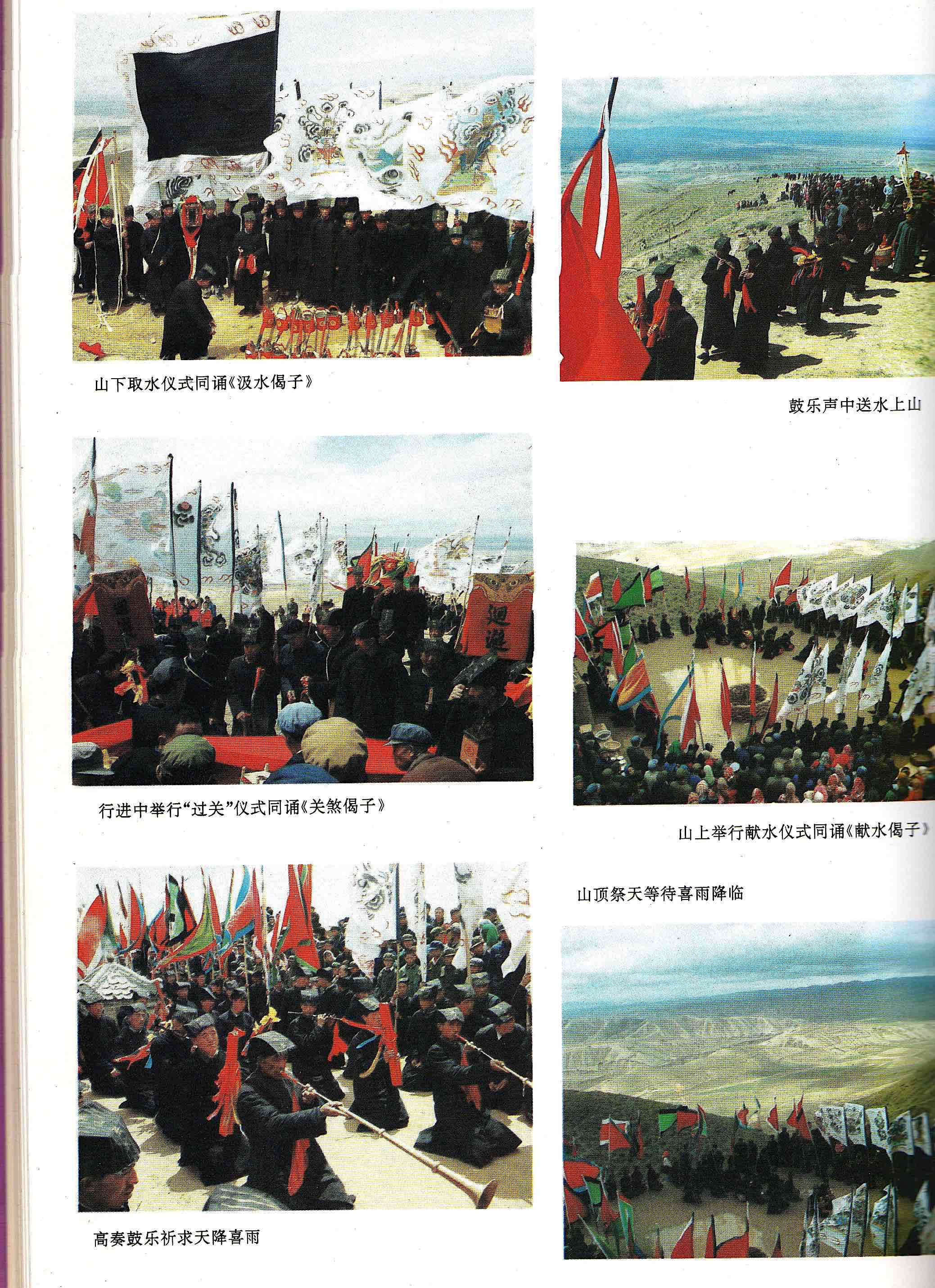

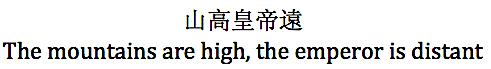

From Xiao Mei’s DVD footage of rain processions in Shaanbei.

In barren mountains barefoot males, stripped to the waist, adorned with head-dresses of willow branches, kneel in the dust to pray hoarsely to the Dragon Kings.

That’s the closing scene of Chen Kaige’s 1984 film Yellow Earth, evoking Shaanbei in 1939 (see also here). An iconic image, of course it’s romanticised, but it’s based on an enduring reality; while successive waves of social change have occurred, processions to pray for rain are still widely performed today

* * *

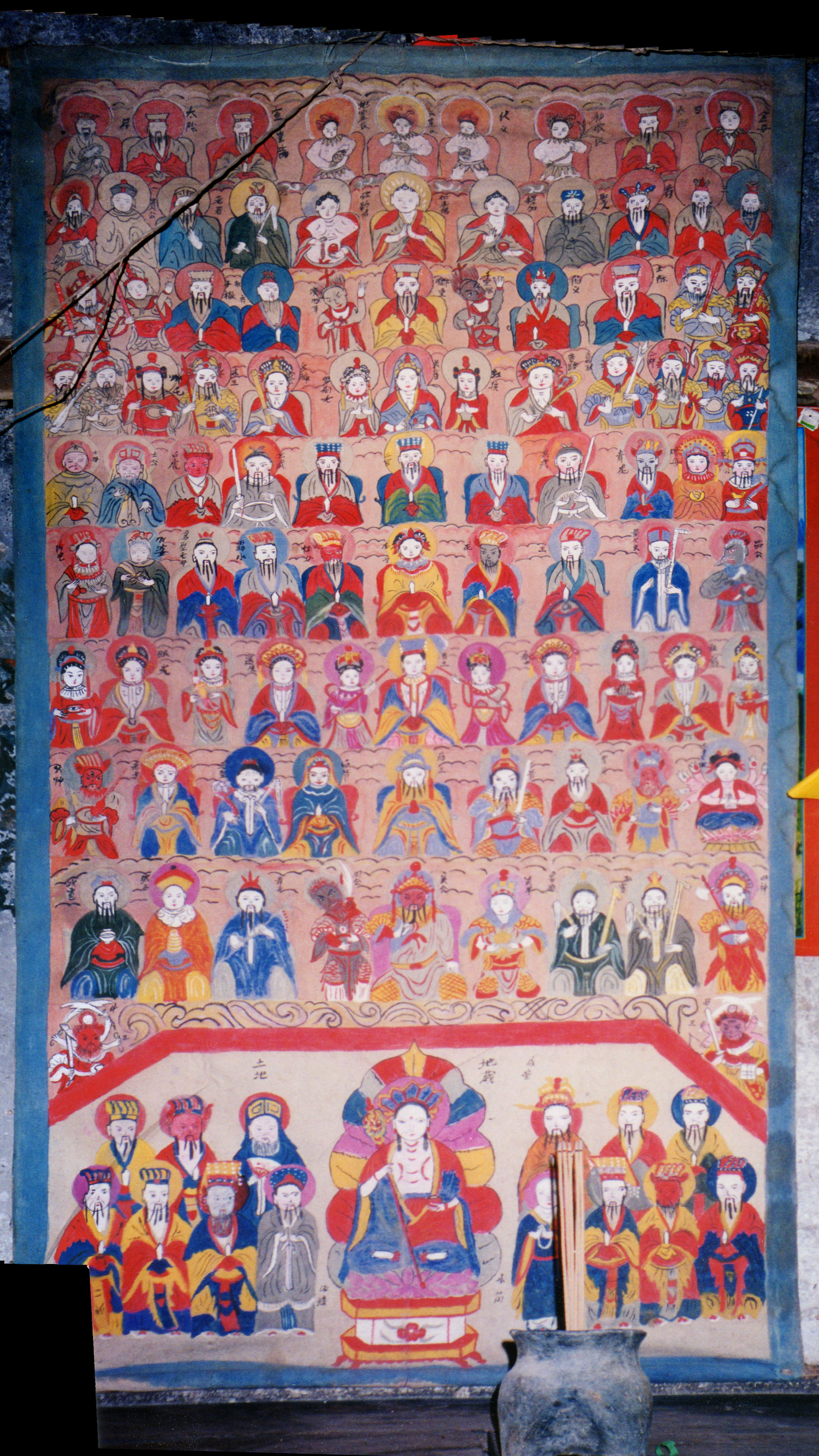

Images of the Dragon Kings in temple iconography are all the rage (see also my post on Elder Hu), but the practical purpose of veneration for such deities is expressed in performance—in this case, rituals to pray for rain.

Daniel Overmyer collects early sources on rain rituals in Chapter 1 of his Local religion in north China in the twentieth century. A slim tome by Dong Xiaoping and David Arkush also gives interesting clues for north China, including Gansu, Shanxi, Henan, and Hebei. [1]

Apart from calendrical rituals like temple fairs, the most important occasional observances are funerals—for which demand, of course, has remained constant. Another important ritual occasion until the 1950s was the ritual procession to pray for rain, held in the summer months—broadly to be subsumed under “rites of affliction” (see my In search of the folk Daoists of north China, p.9). On behalf of the whole community, it is organized by the village leadership.

The extreme weather of north China has long prompted processions to beseech the gods for rain. There is rarely any rain at all from September through to the following June; drought is common—although when it does rain in the summer, it is often torrential, and floods become a serious problem. So rain processions may be held in the summer during times of exceptional drought. But in many areas they may also be calendrical, part of temple fairs (see below), subsumed into Fetching Water (qushui) rituals there. [2]

Indeed, Fetching Water is a routine segment of funeral rituals; in such cases it commonly represents a more generalized prayer for well-being.

Here I’d like to pursue the story through Maoism and the reform era since the late 1970s. As with other areas of religious culture, we can’t simply assume that rain processions ceased after the Communists took power in the 1940s. We may question the official version that they became naturally obsolete after irrigation projects became efficient, but the general picture is that such public “superstitious” extra-village activities were severely restricted.

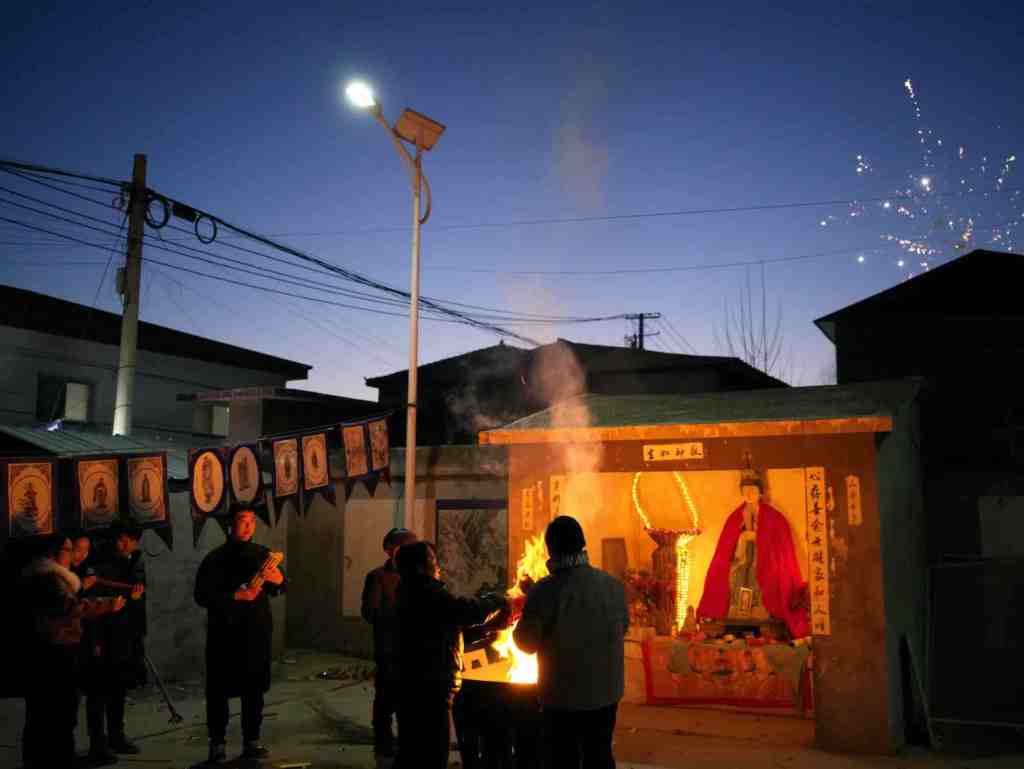

In some regions such processions restored from the 1980s along with the revival of tradition, but since such demonstrations require significant mobilization, as time went by they became less common. The close links between secular and sacred village leaderships had already been attenuated under Maoism; under the reforms urban migration and the loss of community cohesion, along with ever-diminishing reliance on agriculture, have had a major impact. Even so, the “sufferers” left behind still occasionally hold rain rituals.

These rituals are not liturgically complex. Texts to bring rain appear in the Daoist Canon, and local scholars in Tianshui (Gansu) have collected several rain scriptures, though sadly we have no notes on how, or if, they are performed (Dong and Arkush, Huabei minjian wenhua, pp.20–21). Indeed, rain-making, and the Dragon Kings, are just as much Buddhist as Daoist: there are texts in the Chanmen risong. Overmyer also describes clerics reciting scriptures. Some early sources mention jiao Offering rituals performed as part of the observances. However, in modern times rain ceremonies in north China seem rarely to involve Daoist or Buddhist clerics: even household ritual specialists play a minor role. In Hebei the shengguan ensemble of village ritual associations may perform “holy pieces”.

The Hebei plain

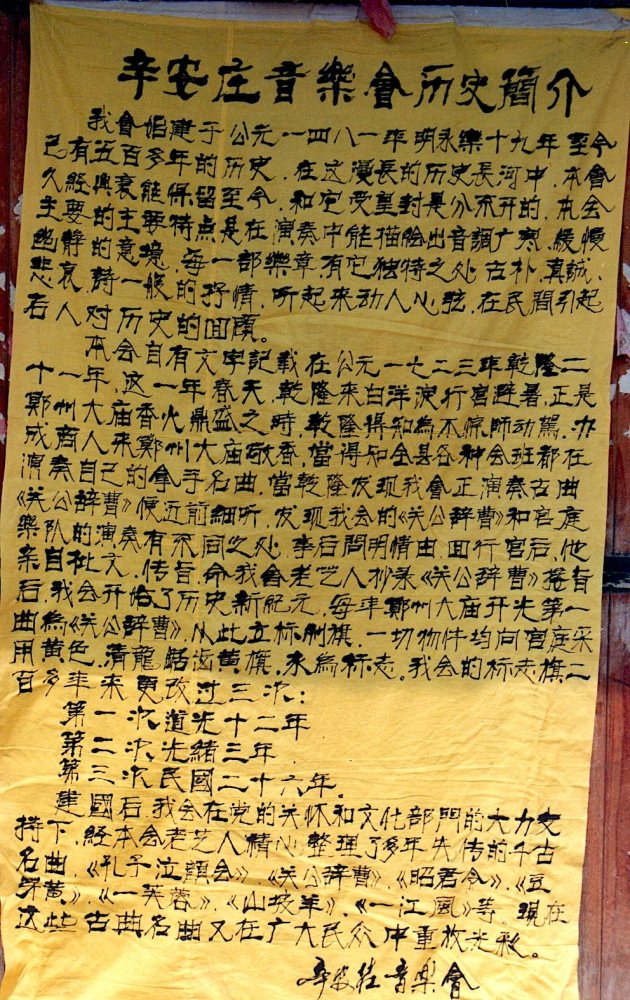

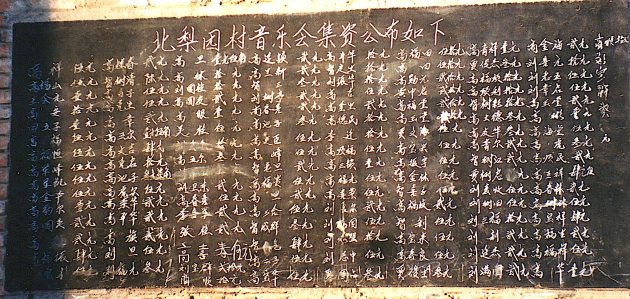

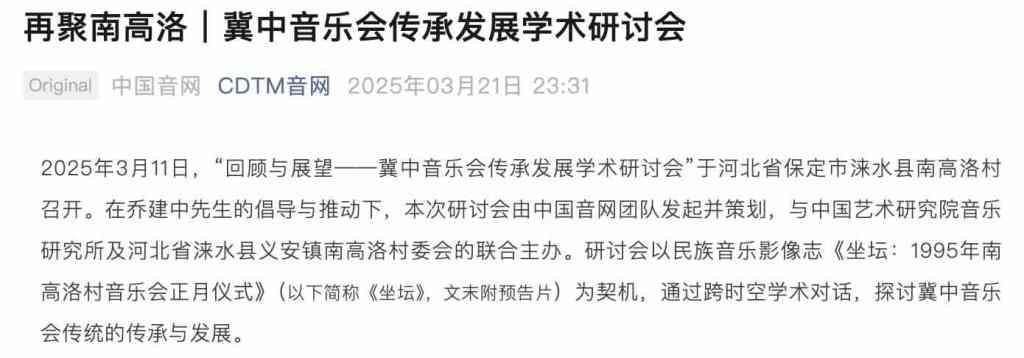

The case of the Hebei plain is rather exceptional, in that most villages had an amateur ascriptive public body for organizing rituals such as funerals and temple fairs, called yinyuehui and overlapping with various sectarian groups.

Our notes from many villages on the Hebei plain south of Beijing (links here; NB also Zhang Zhentao, Yinyuehui, pp.354–61, and Hebei tag) supplement Overmyer’s survey, showing how very common rain processions were before Liberation.

The letters of the Stimmatini Catholic priests from their parish of Yixian in the 1930s show the desperation caused by drought. Despite their faith in the miraculous appearance of the Madonna to protect the village of East Lücun, the priests mock the credulousness of the villagers. They often mention rain processions in Shannan village, in the southern part of Yixian county.

Rain ceremonies are held at a network of pilgrimage sites. These are often occasions when the associations go beyond the boundaries of the village, and establish or confirm links with other villages. As such, they have suffered with greater political control, since solidarity within the village may be threatened when worshippers leave the confines of the village. Thus the Xiaoniu Music Association continued to make the Houshan pilgrimage in the years leading up to the Cultural Revolution, but in a smaller group, and not daring to bring their association pennants with them. Part of the significance of the rain procession, musicians observed shrewdly in Gaoluo, was to demonstrate their adversity to the county authorities, in the hope of remission of taxes.

Rain prayers are most common in mountainous areas, but besides temples, wells and rivers are generally the goal. Most of this area is rather flat, but the mountains in northwest Laishui and Yixian seem to invite rain prayers.

As elsewhere, the main deities worshipped for rain here are the Dragon Kings (Longwang), Guandi (Laoye), and Erlangye, as in Qujiaying.

Gaoluo

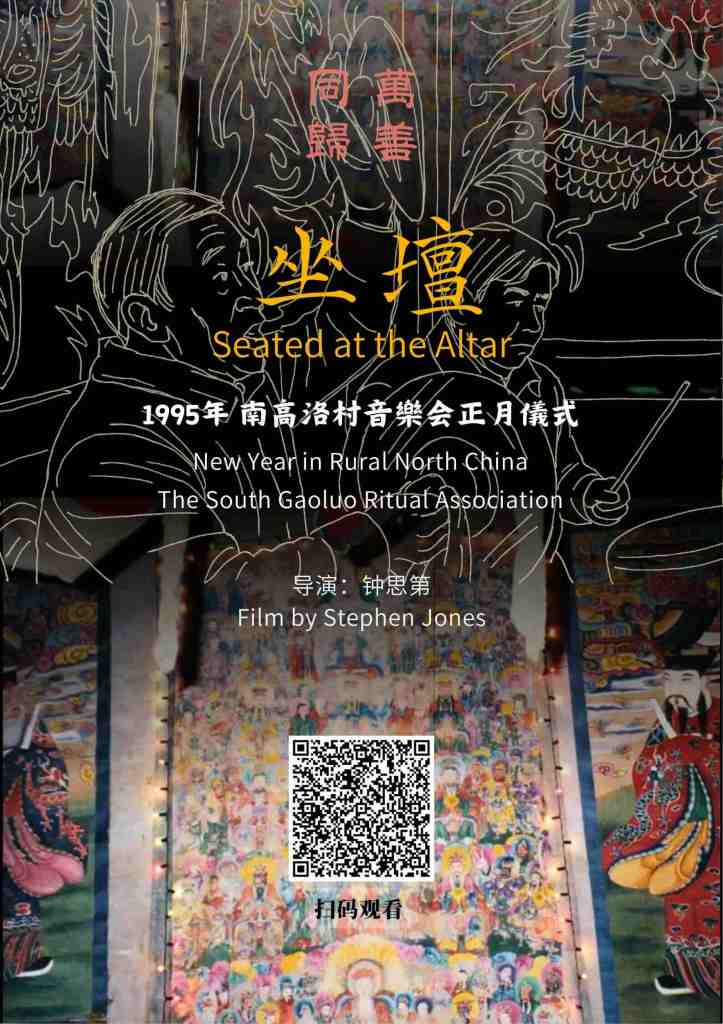

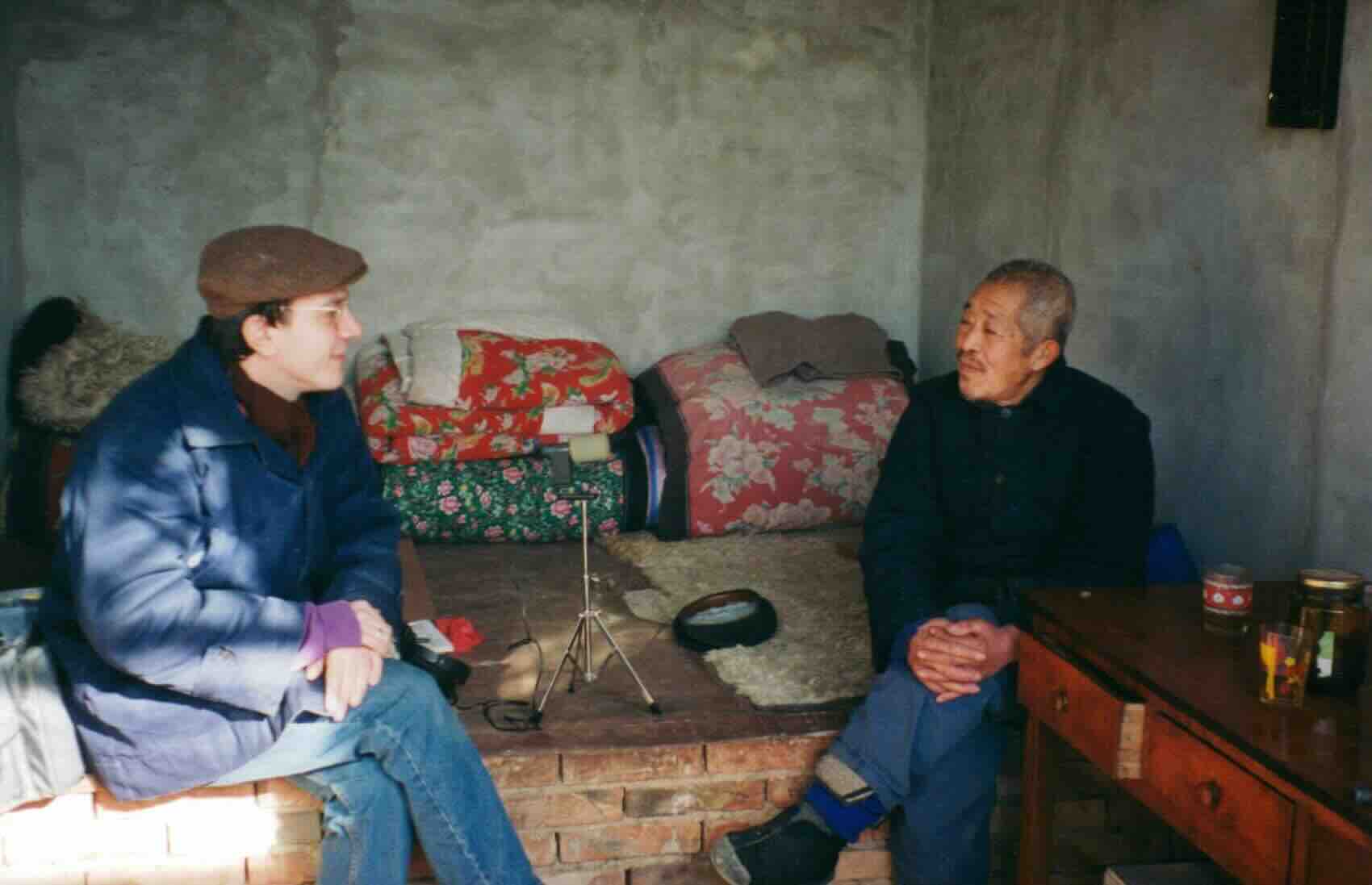

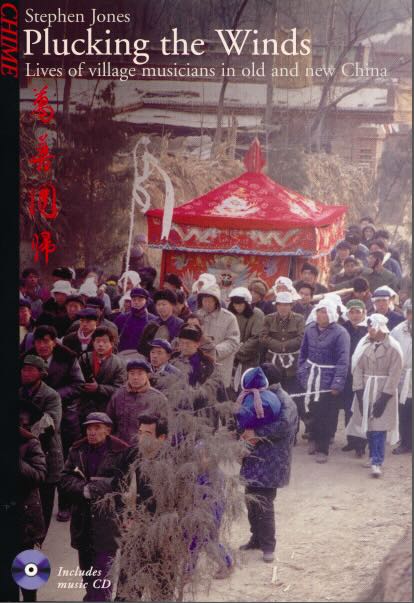

My ethnography of Gaoluo village, in Laishui county, has some notes on rain rituals there (based on Plucking the winds, pp.93–4):

Since droughts were frequent and often disastrous, summer processions to pray for rain were a major part of villagers’ ceremonial life. By the 1950s rain processions in this area were rare, but not non-existent—some nearby villages even observed them in the early 1960s, as the pressures of campaigns and famine forced them to seek divine help. There are still occasional observances in this area today, but they are far less common than in more remote, barren mountainous regions like Shaanbei or Gansu, where they are regular and imposing. As Communist analysts would say, such “superstitions” persist largely where economic progress and ideological pressures have been ineffective. One nearby village which we visited in 1994 had just held a rain procession as a protest against the exorbitant water rates charged by the local authorities.

To pray for rain before Liberation, Gaoluo villagers once used to make a pilgrimage to Baiyutang in the mountains of Fangshan, quite distant, about 60 Chinese li (30 km) north, where they “fetched water” from a big gulley where turtles swam, taking a statue of the Dragon King. They filled a gourd with the water and took it back to the village. Venerable Shan Zhihe also recalled a rain pilgrimage to Xianggai village 10 li to the south, near which there was an auspicious well in the grounds of the Dragon Kings Temple. Someone from Bailu village had to come and take water from the well, since the Dragon Kings’ mother was said to come from there; she had married to Xianggai. Villagers could only take water from the well when there was a drought. They lowered a jar made from willow branches into the water, drawing it up with a pulley. They then emptied the water into a gulley nearby, from where it flowed into the Juma river towards Gaoluo.

Before 1932 young Shan Zhihe had himself gone twice on the procession to Xianggai, and had seen how efficacious it was: “it usually rained even before the water could reach the river. If it didn’t work the first time, it always rained the second time!” Our friends knew of the custom of putting a god statue out to make it suffer in the sun until it rained, which is commonly attested, but no-one recalled having to do so.

The statues taken by the villagers on these processions were of the Dragon Kings or Guangong (Laoye). The statues used for pilgrimages were smaller portable versions of the big clay ones in the temples, about a metre high, but not every village had them, and so rain-prayers were sometimes known as “stealing the statue” (touxiang), since they had to borrow one from a nearby village. Of course, it was a formal ritual procedure. They made a sedan for the statue out of willow-branches and carried it on poles. The ritual association would lead the procession; Cai Fuzhong, father of Party Secretary Cai Yurun, had fired the three-cartridge cracker-firer. The borrowing village would usually repaint the statue; egg-yolk, also used for the animation of god-statues, was used. Finally they returned it to the temple with great ceremony.

When the village men went to pray for rain, the ritual association decked out its “public building” with god paintings and incense. The men parading in front of the sedan sang “songs of rejoicing” (xige 喜歌)—a rare admission of any former folk-song tradition. The association would lead the procession; Cai Fuzhong, father of talented Yurun, fired the three-cartridge cracker-firer. Part of the significance of such processions, our friends observed shrewdly, was to demonstrate adversity to the county authorities, in the hope of remission of grain taxes; the Baiyutang procession actually stopped off at the county government yamen.

The second time Shan Zhihe went on the Xianggai procession was in 1930, when he was 12 sui and studying at the village private school, just before the Catholic church was built. Erudite Shan Fuyi recalled that the village’s last rain procession was in the summer of 1949 just after [the village] Liberation, when he was in 2nd grade at primary school. Though it was quite a small-scale occasion, the ritual association played. The villagers toured a statue of Laoye which they had “stolen” from Xiazhuang village just east of the river. After parading through North and South Gaoluo villages, they had the statue repainted, inviting a painter and ritual paper maker called Yang, from South Dawei; he repainted the statue in the ritual association’s “public building”. Some musicians even recalled a rain pilgrimage when Shan Ling was at secondary school, which must have been in the mid-1950s, when collectivization was already under way. That time, they claimed, they made the more distant procession to Baiyutang.

A similar ritual which soon became obsolete in Gaoluo was “setting out the river lanterns” (fang hedeng), an exorcistic ceremony still performed today by ritual associations on 7th moon 15th in several other parts of the region. Genial Shan Yude recalled seeing it in Gaoluo for the last time when he was 8 sui, around 1949. Lanterns were placed in a paper boat and in hollowed-out gourds to light the way for the souls of the drowned and avert flooding, while the association perfomed. The ritual may have been discontinued largely through official disapproval, though the river was anyway becoming more shallow.

Yixian county

Just west of Laishui county, in Liujing at the foot of Houshan, the guanshi assistants of the village’s four ritual associations go to a spring on Houshan called “water room” (shuifangzi) to offer incense and pray for rain. Menstruating women are forbidden to go, since they would offend the Dragon Kings and prevent rain falling. In 1985 the people made Dragon Kings and Dragon Mother statues. Around 1991 the four assistants were asked by the villagers to pray for rain; the cadres didn’t interfere, but the associations didn’t go because it would take too much arguing between the ritual representatives of the four villages.

Nearby in Baoquan, Li Yongshu (b. c1926) said they still performed rain ceremonies, burning incense and reciting scriptures—he said there was no special ritual manual, but the Ten Kings scroll was often used. They sang the Hymn to the Dragon Kings, inviting other gods like Laoye or even Houtu—the people decided which, depending on which they believe in. Li Yongshu had first prayed for rain when 17 or 18 sui (c1943), when five villages combined to take statues of the Dragon Kings and Laoye on tour.

Further south in Yixian, Shenshizhuang villagers used to go to the summit of Zijinguan, 100 li distant. They went in 1947, and again after the temples were destroyed in the Four Cleanups, around 1965. Then the brigade organized the ritual association to play on the pilgrimage; wearing hats made of willow branches, they took their own provisions, while locals provided firewood. They played any pieces, there was no fixed repertory. That very evening as they were walking home, it started to rain!

But most elderly villagers describing rain ceremonies remembered them only as a thing of their youth. Even Wei Guoliang in Matou described it thus. The last time his son’s wife recalled was in the 1950s. According to Wei, it was also called “catching the turtle” (zhua gui), just like an exorcism. There were two ritual sites on Houshan to seek water: Matou zhai and Taohua an. They used to go for three days, bearing aloft statues of the Dragon Kings, the ritual association playing in front. Daoist priests recited the Mantra to Mulang (Mulang zhou); Wei didn’t know what the Buddhist priests recited.

East Baijian village used to perform a rain ceremony called Offering for Hailstones (ji bingbao 祭冰雹). They went on procession to the Central Yi river to float lotus lanterns (or river lanterns?), with the ritual association accompanying. They still did it once after the Japanese invaded, but it became very rare thereafter. They had prayed for rain clandestinely in 1962 and even in 1964, by agreement with the village brigade, but they didn’t dare use the shengguan wind ensemble of the ritual association.

Remarkably, in the 7th moon of 1994 the East Baijian village men again prayed for rain, wearing headgear of willow branches and bearing aloft an image of Laoye. Unlike the clandestine observances of 1962 and 1964, this time the ritual association accompanied the procession with their shengguan. Despite the common official claim that irrigation has rendered such superstitious observances obsolete, this ceremony was precisely a kind of demonstration against the exorbitant water rates charged by the government. The authorities were charging the village 28,000 yuan for the irrigation of their land for only a dozen or so days—elders remembered when it only cost 300 yuan for a whole month! The villagers bore aloft an image of Laoye. So they still felt that they had to “rely on Heaven to eat” rather than on the government, or science.

Dingxing county

Zhang Mingxiang, former Daoist priest at the Donglin si temple in Dingxing county town, recalled their prayers for rain. The people bore aloft a statue of the Dragon King (Erlangye?), with a bell around its neck. They wore willow headdresses, went barefoot, even the county chief. There were wells at the Nanyin si and Longmu miao temples south of the town, one for praying for rain, the other for hailstone rituals. They took a bucket of water from the well, sprinkled it on the ground as they lit incense, set fire to an old gu tree, and recited the Zaotan shenzhou 早壇神咒 manual. If their prayers were answered, they staged an opera in the autumn. Here the last rain prayers were held in 1937–8—after that it became impossible because of the fighting.

Xiongxian and Renqiu counties

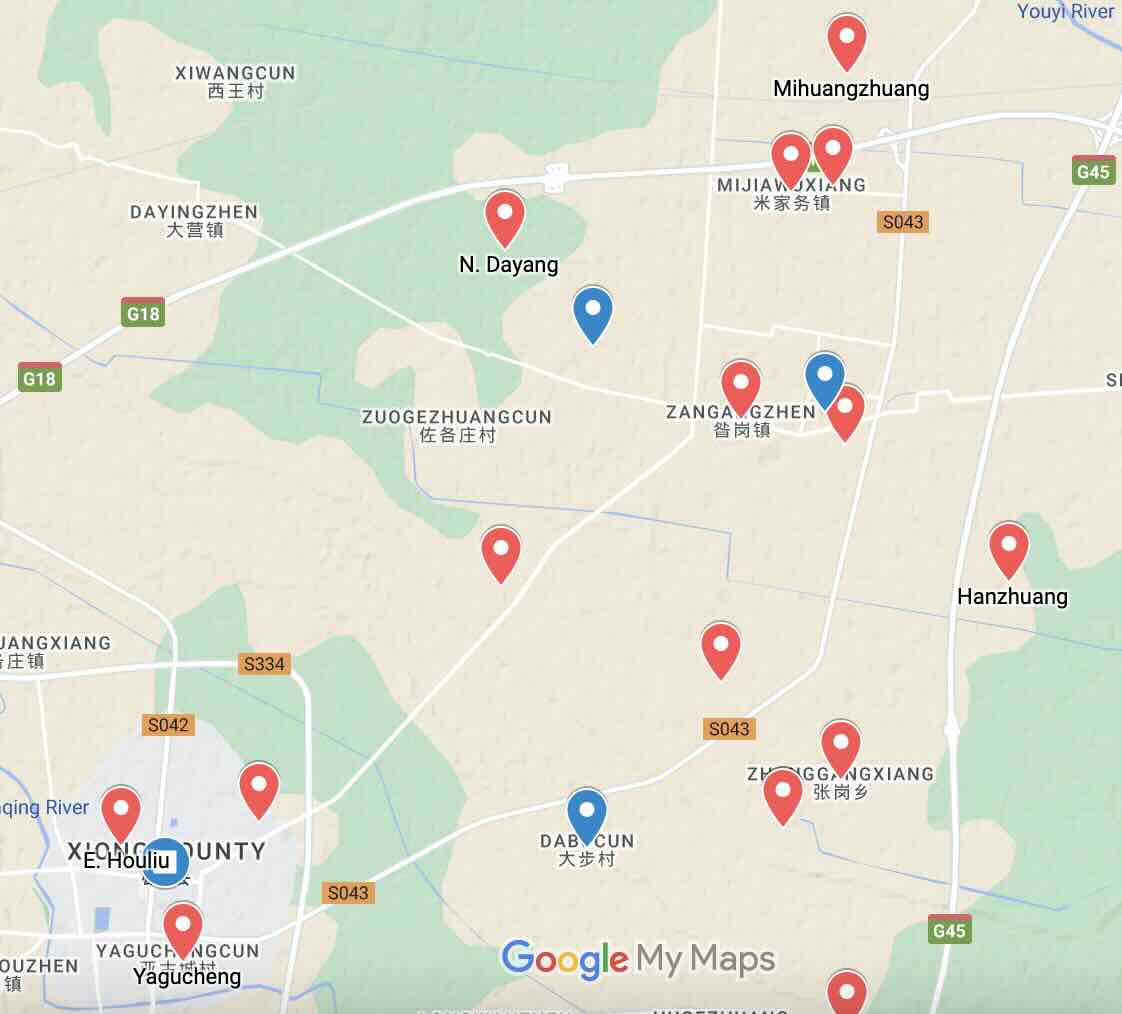

We found more clues to rain processions in the villages of Hanzhuang, Gegezhuang, Dabu, and Mihuangzhuang.

In Hanzhuang, Xie Yongxiang recalled rain ceremonies, which hadn’t been performed in the region since 1937—the last time was when Xie was 12 sui, his wife 15, the year they got married! For the first three days they took an image of Laoye (Guangong) outside the temple to expose it; after the third day the ritual association and the villagers, with willow branches on their heads, took it on a tour in a sedan. If it still hadn’t rained after nine days then they took the statue home. The ritual association played small pieces (lingqu 另曲), mainly three melodies given the acronym of Jin–Wu–Cui (Jinzi jing, Wusheng fo, and Cuizhulian).

Gegezhuang had last prayed for rain around 1945. They “beseeched Elder Wang”. The incense head (xiangtou, here the leader of the ritual association) was in charge. but the chaozi association played, not the ritual association. They went to the Yaowang miao temple, to beseech the three Wang Elders, of whom Liu Wangye (Yaowangye) was in charge. They took the Yaowang statue on a tour of the village—the last time was around 1945.

They had heard a story of nearby Dabu village praying for rain in the late Qing. There was not a cloud in the sky, but as soon as the incense head took the sword of fate (mingjian 命剑) of Yaowang and pointed it to the northeast, clouds appeared, and before long there was a downpour. But it fell only on the village; there was not a drop outside the village! In cases when it didn’t rain, they punished the incense head by locking him up for a few days.

Mihuangzhuang had a Yuwang miao temple (alas we omitted to clarify if this was Yu the ancient emperor or Yuhuang!). Two red poles, 5 or 6 metres long, were held horizontally, with a cover (mogai) hung from them. They brought out the statue of Guangong (Laoye) and placed it on the structure, parading to a large open space. People wore tabards. Everyone faced outwards in a circle, and the statue was paraded all round. Two people called “bridge-grabbers” stood on the poles, in the “eight-step zen position”, and while the carriers raced as fast as they could, they had to stand firm. There was no incense head—the organizer was just a senior villager. Again the percussion of the chaozi association, not the yinyuehui ritual association, performed.

Further south on the plain, North Hancun in the south of Renqiu county also went on a tour. Wherever the Dragon King Elder of a village was efficacious, they took it on tour around the villages, and the receiving villagers would provide refreshments of tea and snacks. The procession was accompanied by large drums, but no shengguan, and the nuns of the village didn’t take part. procession often went on for seven days, and if no rain, they extended it for three further days. There were “songs of rejoicing” for “red rituals” such as weddings and building a house—for which the village had a special singer.

Tianjin

We have a description of rain-prayers “in the past” in the greater Tianjin area, in which “dharma-drumming associations” (fagu hui 法鼓会) playing shengguan music took part. One would like an update.

Praying to Dragon King Elder, the procession was led by pennant-bearers. A gong was sounded to Open the Way; four men carried a statue of the dragon, one carried on his back a tortoise-shell made from a sieve, holding a large mace in each hand; another man pulled along a leech (representing the aquatic kingdom); and a man dressed as a leech wore a leather coat inside-out, his face painted red and black, wearing a “god hat” (foguan, known as mazi) made of paper, with a painting of Dragon King Elder on it, attached to the head with red string.

Immediately behind followed the incense bowl, and barefooted villagers. The Dharma-drumming association with their shengguan music brought up the rear (Guo writes “blowing”, not just percussion). As they proceeded, the musicians played the percussion item Changxingdianr, as someone shouted “Black dragon head, white dragon tail, day and night come to bring water”. When they reached the riverside all made kowtows, burned incense, chanted prayers, and the association played various melodies. Finally they threw the Dragon King statue into the river and dispersed, making their way home.

Shanxi

For north Shanxi, I have given some clues to former rain processions in Yanggao, home of the Li family Daoists. [3] Going south, in Xinzhou before Liberation, “rain-thanksgiving” (xieyu) did require Daoist and Buddhist clerics. Rain ceremonies continued there after Liberation, and were still performed in the 1990s, though it is unclear if ritual specialists took part; we were even told of a village that held a rain procession in 1972, during the Cultural Revolution. Similarly, rain ceremonies persisted in the Wutai area after Liberation, and even took place on the quiet through the Cultural Revolution, continuing since.

Catholics in Shanxi also hold ceremonies for rain, like the Catholic village of Wujiazhuang, Xinzhou county, that we visited in 1992. Henrietta Harrison’s fine work on the Catholics of central Shanxi contains several instances. [4]

Daoists took part in rain prayers in the Liulin area of the Lüliang region in west Shanxi (Dong and Arkush, Huabei minjian wenhua, p.74), which belongs culturally with Shaanbei.

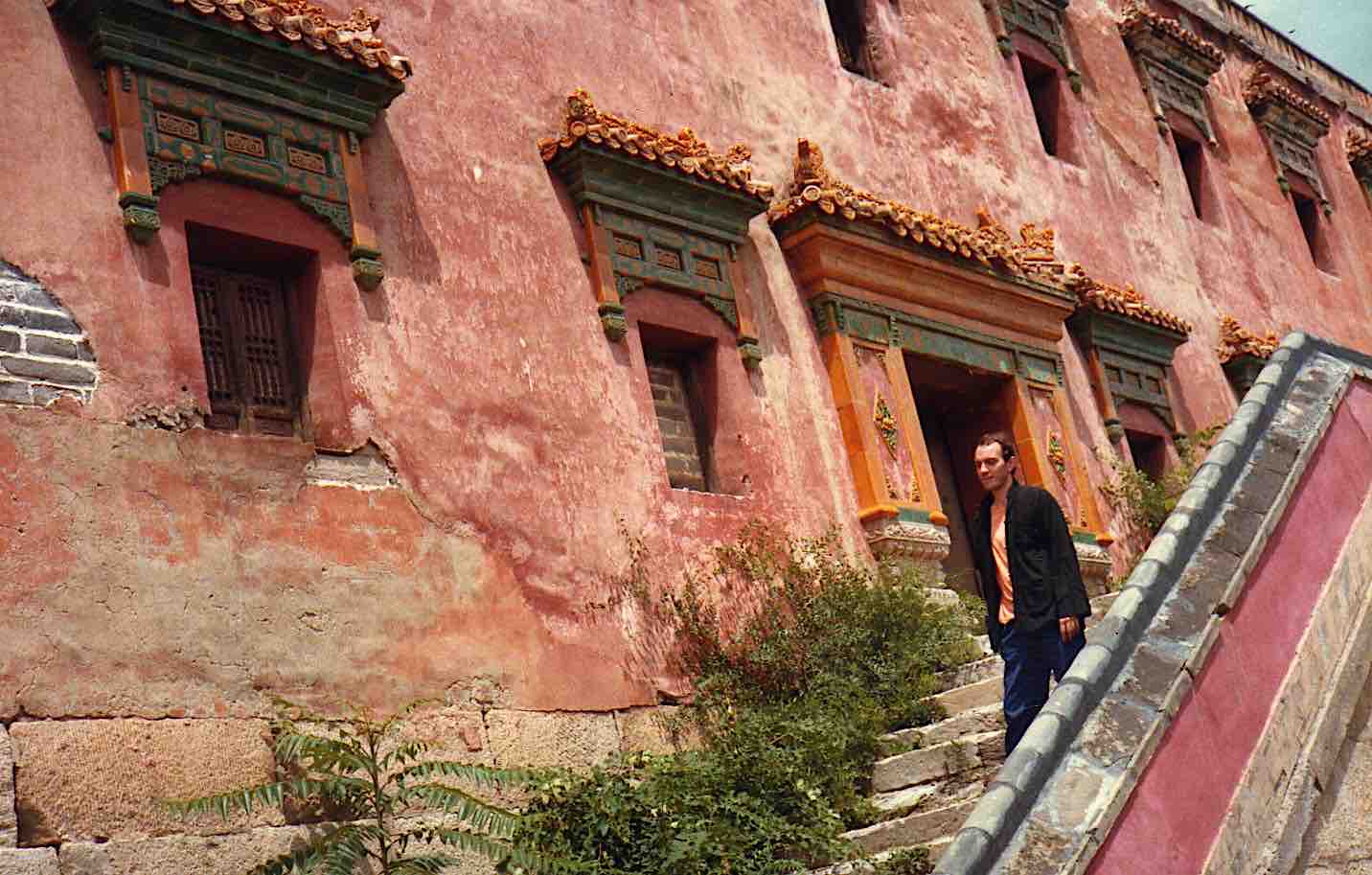

Shaanbei

In Shaanxi, pilgrimages to the mountains south of Xi’an in the sixth moon remain popular: see map here. [5] But we have more detailed reports from Shaanbei, the northern part of the province. [6]

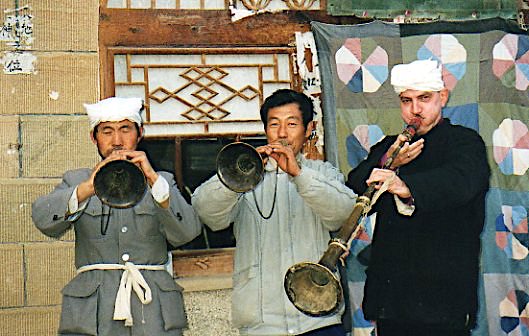

Rain processions in Shaanbei are commonly referred to as “shouldering the god sedan” (tai shenlou) or “shouldering the Dragon Kings” (tai Longwang). They mostly take place in the searing heat of the 6th moon. They are organized by a committee of senior male villagers, with all households contributing—except that the women are not allowed to observe. The route is thought to be determined by the gods: in one village they had to stop because the gods were leading them over a cliff.

As to soundscape, male villagers sing (or “shout”, as they say) in solo and choral response, the “rain master” playing gong, another villager playing drum, while shawm bands may play on arrival at ritual sites. Since many Dragon King temples are on remote hillsides, opera stages are often in the village; on return to the village an opera troupe is commonly invited to perform to thank the gods.

Notes from our 2001 visit to the Jiaxian opera troupe (my Ritual and music of north China, vol.2: Shaanbei, pp.17–19):

They take work all over the southern Yulin region. Sometimes (mainly in the winter) opera troupes are invited for weddings and funerals, costing around 1,000 yuan. But their main context is temple fairs from the 1st to the 8th moons, mainly in the six southern counties of the Yulin region—without temple fairs, as Li said, they would be out of business. They take part in over thirty temple fairs, large and small—most such contexts demand that they perform a series of items over three days. They also perform “three or five times a year” for villages holding rain prayers, from the 5th to the 7th moons.

Guo Yuhua‘s chapter on Yangjiagou in her Yishi yu shehui bianqian opens with an account of a rain ritual there. A chapter on Shaanbei rain rituals by Xiao Mei 萧梅,

- “Huwu hujie qi ganlin: Xibei (Shaanbei) diqu qiyu yishi yu yinyue diaocha zongshu” [The buzz of praying for sweet rainfall: field survey on ritual and music of rain prayers in the northwest (Shaanbei) region], in Tsao Poon-yee [Cao Benye] (ed.), Zhongguo minjian yishi yinyue yanjiu, Xibei juan [Studies of Chinese folk ritual music, Northwest vol.] (Kunming: Yunnan renmin chubanshe, 2003, with DVD), pp.419–88,

is enriched by two sequences on the accompanying DVD, filmed in 2000 at Longyangou and the Black Dragon Temple (for which Adam Chau‘s book Miraculous response is a must-read), and documented in her chapter. As ever, even a short film is worth hundreds of pages of silent, static textual accounts. Some screengrabs appear at the head of this article.

Xiao Mei begins her account like a traditional sinologist, with a useful survey of early historical sources, complementing those of Overmyer. But then she pursues the theme with a rare participant’s description, using an anthropologist’s eyes and ears. The only woman allowed to participate was a spirit medium (p.443).

And while you’re about it, do read Xiao Mei’s long article on spirit mediums in distant Guangxi (again with DVD), cited in n.4 here.

This documentary, filmed at a village in Hengshan county in 2005, is also worth watching.

Ningxia

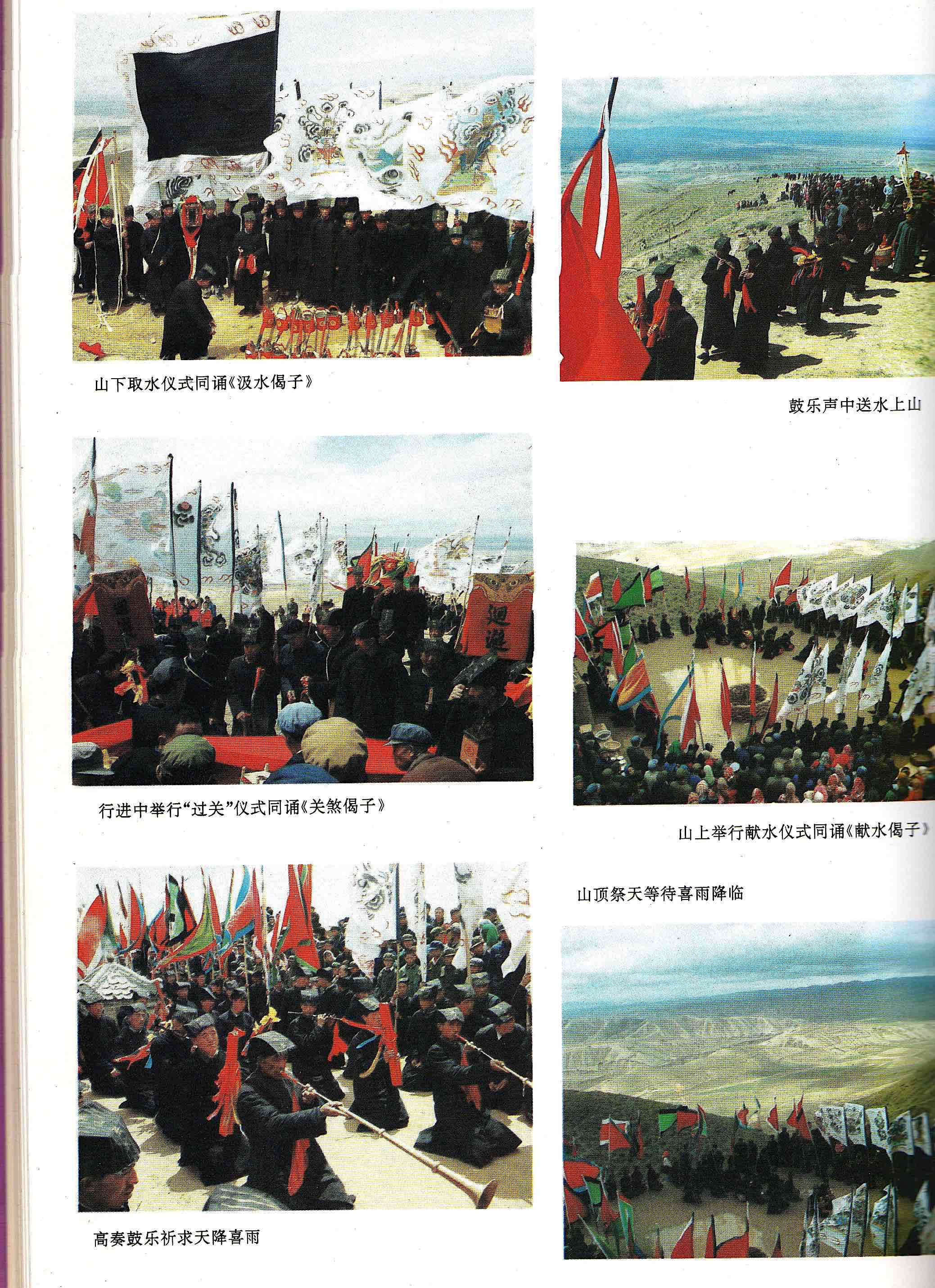

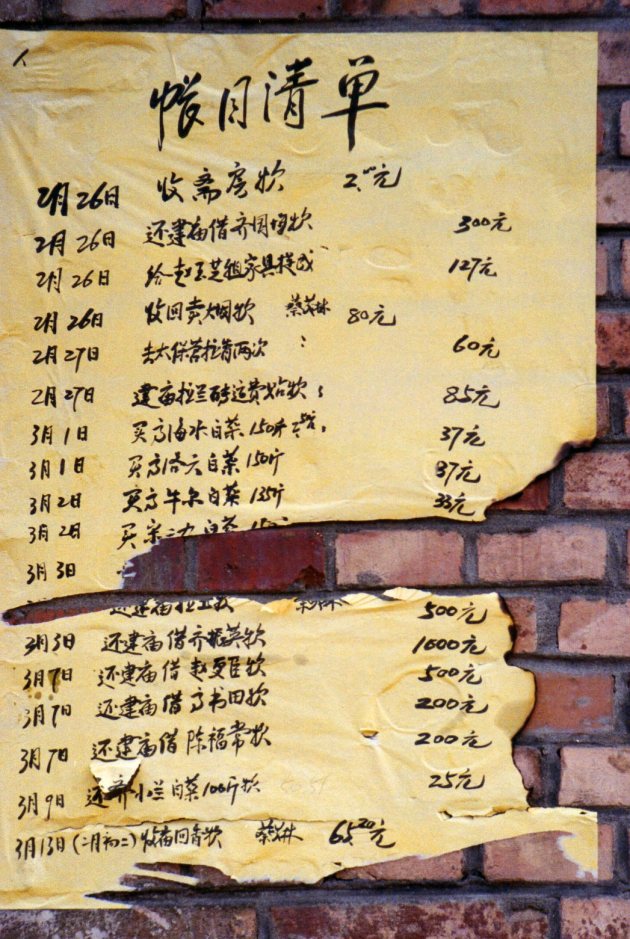

Several volumes of the Anthology gives further slim leads to rain ceremonies, such as that for Ningxia, which has photos of the qingmiao shuihui Green Shoots Water Assembly procession on Lianhuashan mountain in Tongxin county—grandest of a network of calendrical observances for rain, with its main day on 4th moon 15th. [7]

I may add that the photos in the Anthology often surpass the texts in suggesting promising leads—even if in this case they considerably predate the iniquities of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, this event was recreated and elaborated quite soon after the 1980s’ revival with involvement from cultural cadres.

* * *

These piecemeal instances merely hint at the ubiquity of rain rituals in north China before the 1950s. As ever, such rituals might be large or small in scale. But as with all aspects of religious behaviour, they have undergone a fundamental change, not just since the 1950s but under the reforms, with rural populations depleted and community cohesion attenuated. Still, those rituals that are still performed are not some exotic vestige of “heritage”, but a sign of ongoing suffering. Contemporary ethnographic accounts are not just a means of imagining the dry accounts of past rituals, but a major part of our understanding current society.

[1] Dong Xiaoping and David Arkush, Huabei minjian wenhua, pp.20–22, 72–5, 106–13. For further early sources, see articles by Zhang Zhentao and Xiao Mei in this post.

[2] E.g. Wu Fan, Yinyang, gujiang, ch.3; see also Yuan Li, “”Huabei diqu qiyu huodongzhong qushui yishi yanjiu” [The Fetching Water ritual in north Chinese rain ceremonies], Minzu yishu (Guangxi) 2001.2, pp.96–108 and 121. For Fetching Water in Yanggao funerals and temple fairs, see also my film, and the DVD with my Ritual and music of north China: shawm bands in Shanxi.

[3] See my Ritual and music of north China: shawm bands in Shanxi, pp.72–4; Wu Fan, Yinyang, gujiang, ch.3. Further leads for other areas of Shanxi are to be found in Wen Xing 文幸 and Xue Maixi 薛麦喜 (eds.), Shanxi minsu 山西民俗 (Taiyuan: Shanxi renmin cbs, 1991), pp.399–400. Cf. Wang Lifang 王丽芳,”Minzhong qiuyu xisude shengtai jingjixue sikao: yi Shanxi minjian qiuyu xisu weili” 民众求雨习俗的生态经济学思考——以山西民间求雨习俗为例, Shengchanli yanjiu 2006.6.

[4] E.g. The man awakened from dreams: one man’s life in a north China village, 1857–1942, and The missionary’s curse, pp. 104–7.

[5] Tiny clues in Zhongguo minjian gequ jicheng, Shaanxi juan: text 920, transcriptions 926–7.

[6] For some sources, see my Ritual and music of north China, vol.2: Shaanbei, pp.22–3. Cf. Zhongguo minjian gequ jicheng, Shaanxi juan, text p.572, transcriptions (from Dingbian, Jiaxian, and Fugu) pp.606–8.

[7] Transcriptions, with texts, from Lianhuashan and Xiangshan, as well as Pingluo and Yinchuan, in Zhongguo minzu minjian qiyuequ jicheng, Ningxia juan, pp.713–46. See also Zhang Zongqi 张宗奇, Ningxia daojiao shi [History of Daoism in Ningxia] (Beijing: Zongjiao wenhua cbs, 2006), pp.210–11, 261–7. The term “water association” (shuihui) is quite common; though some such urban groups were more or less secular—local militia for protection against fire and robbers—in rural north China they were often associations for rain, as in the pilgrimages just south of Xi’an (for refs. see my In search of the folk Daoists, p.81). The term Green Shoots has only been attached since 1983.

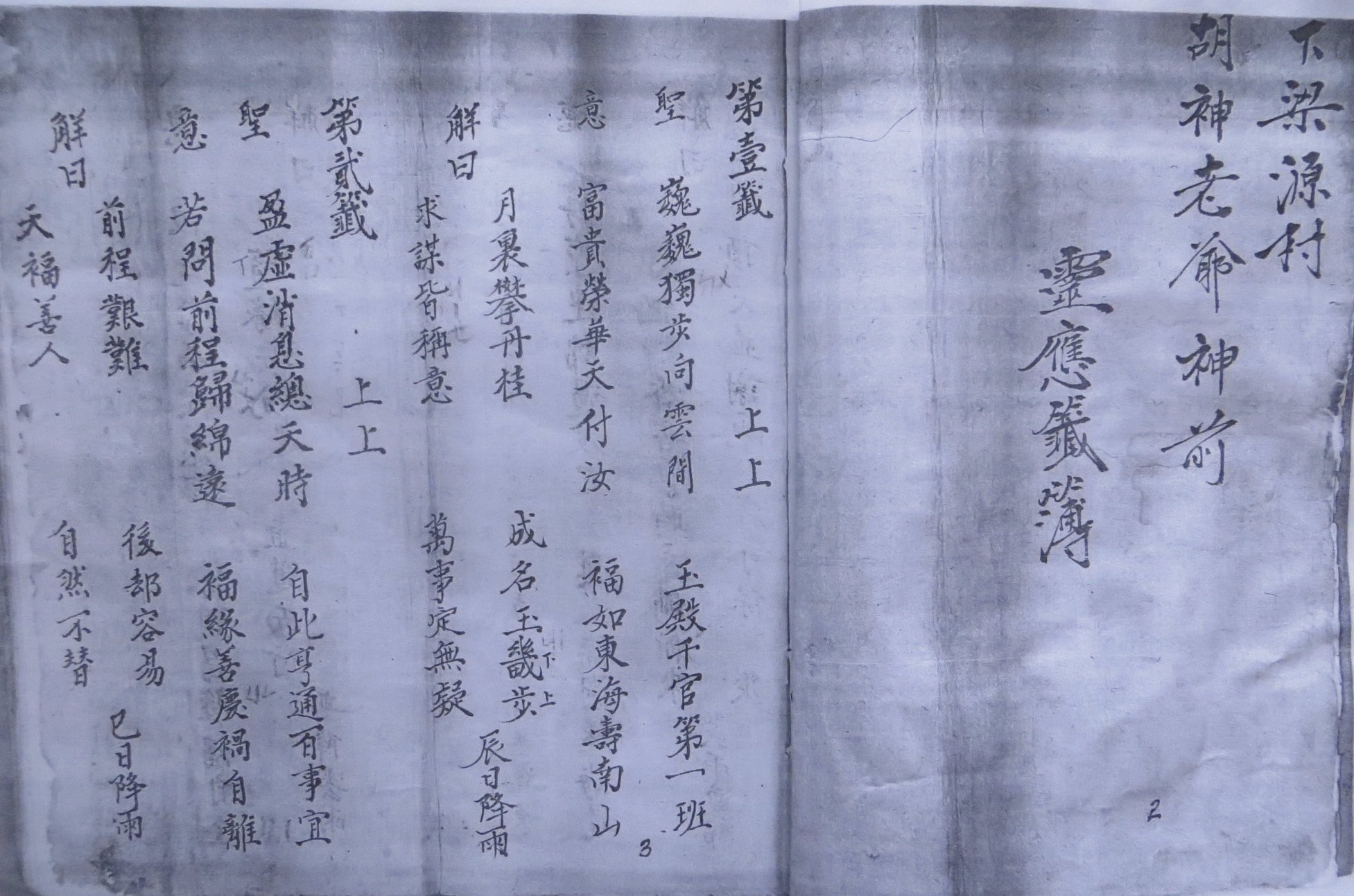

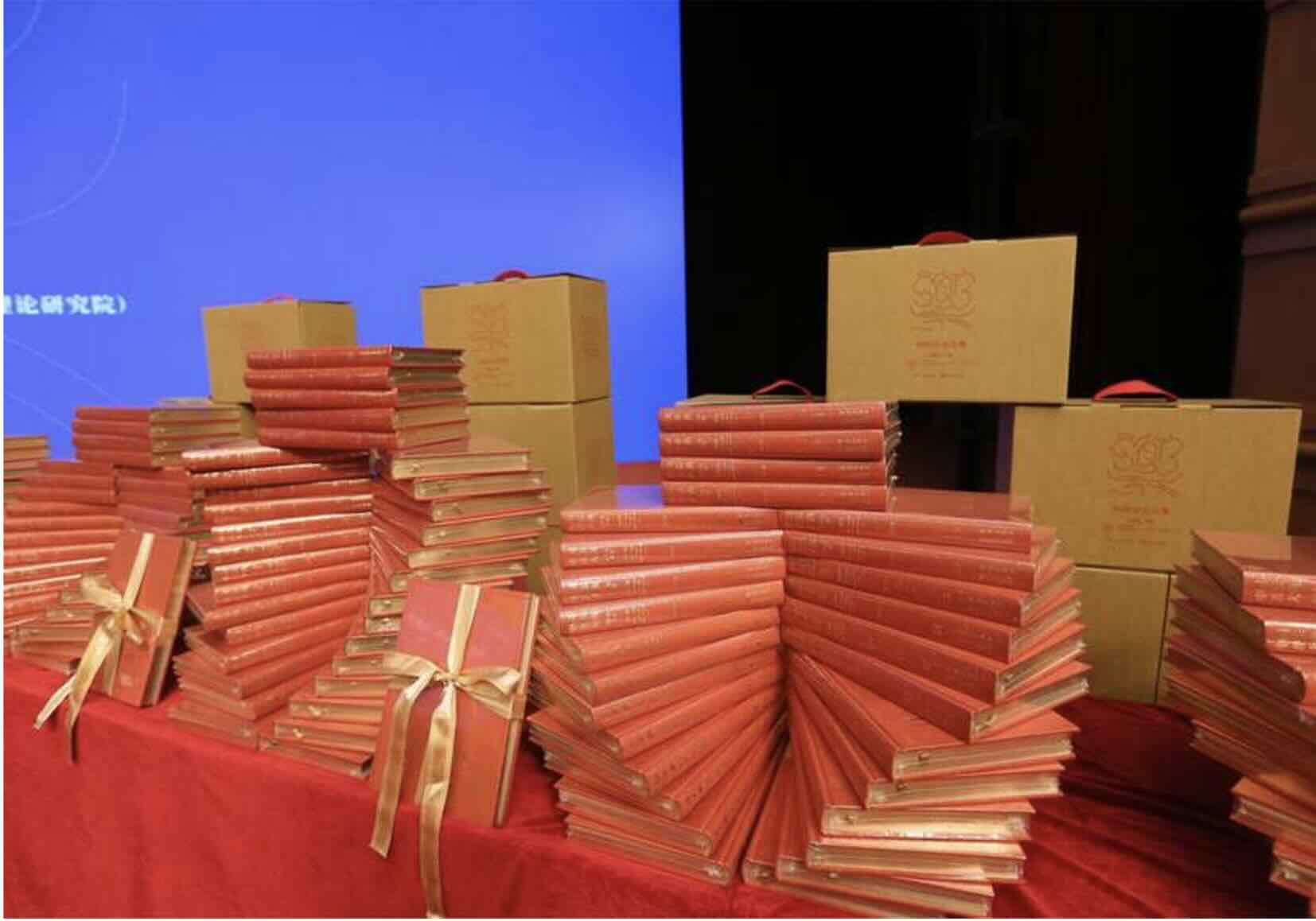

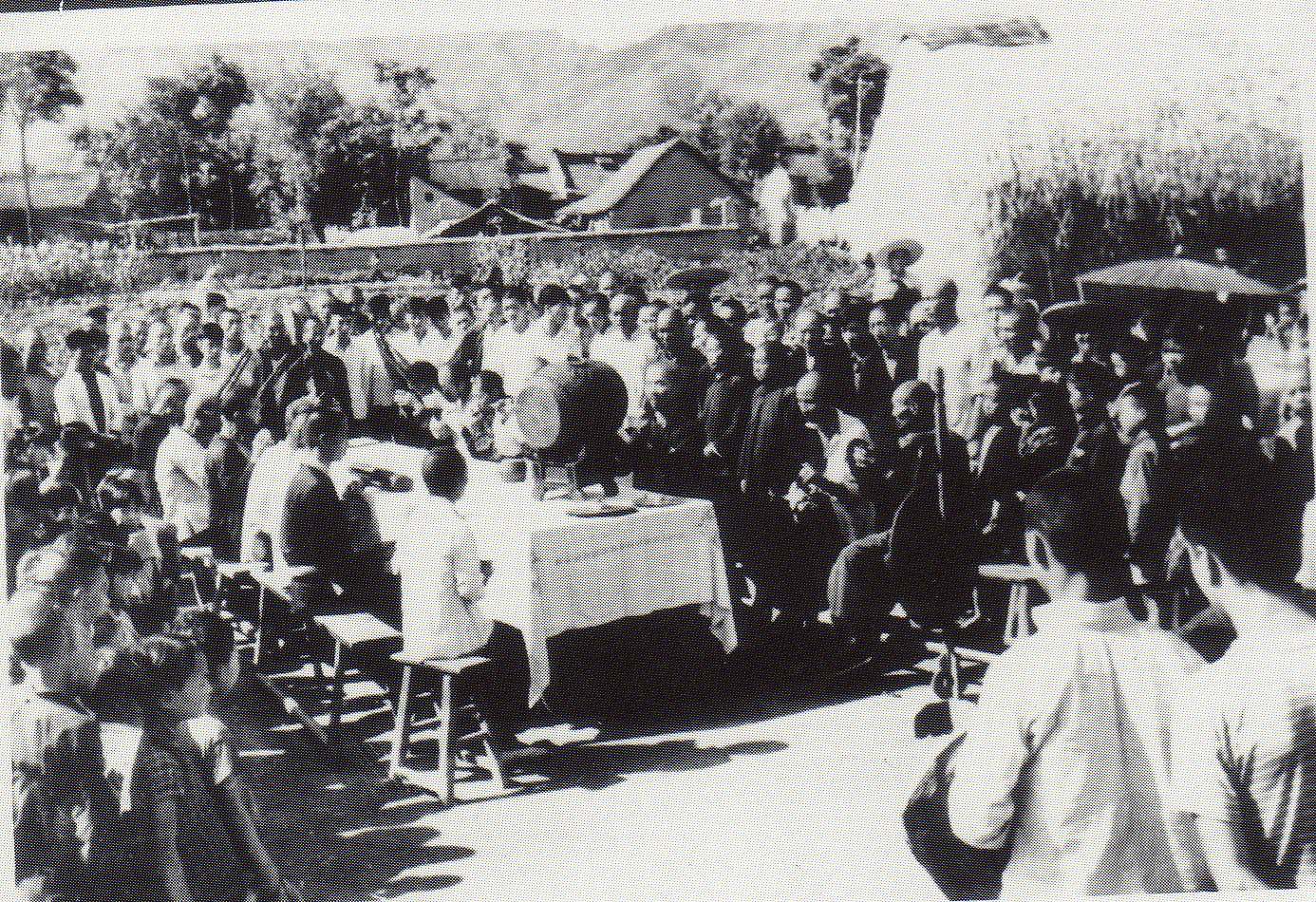

The Yuepu bian team, 2017.

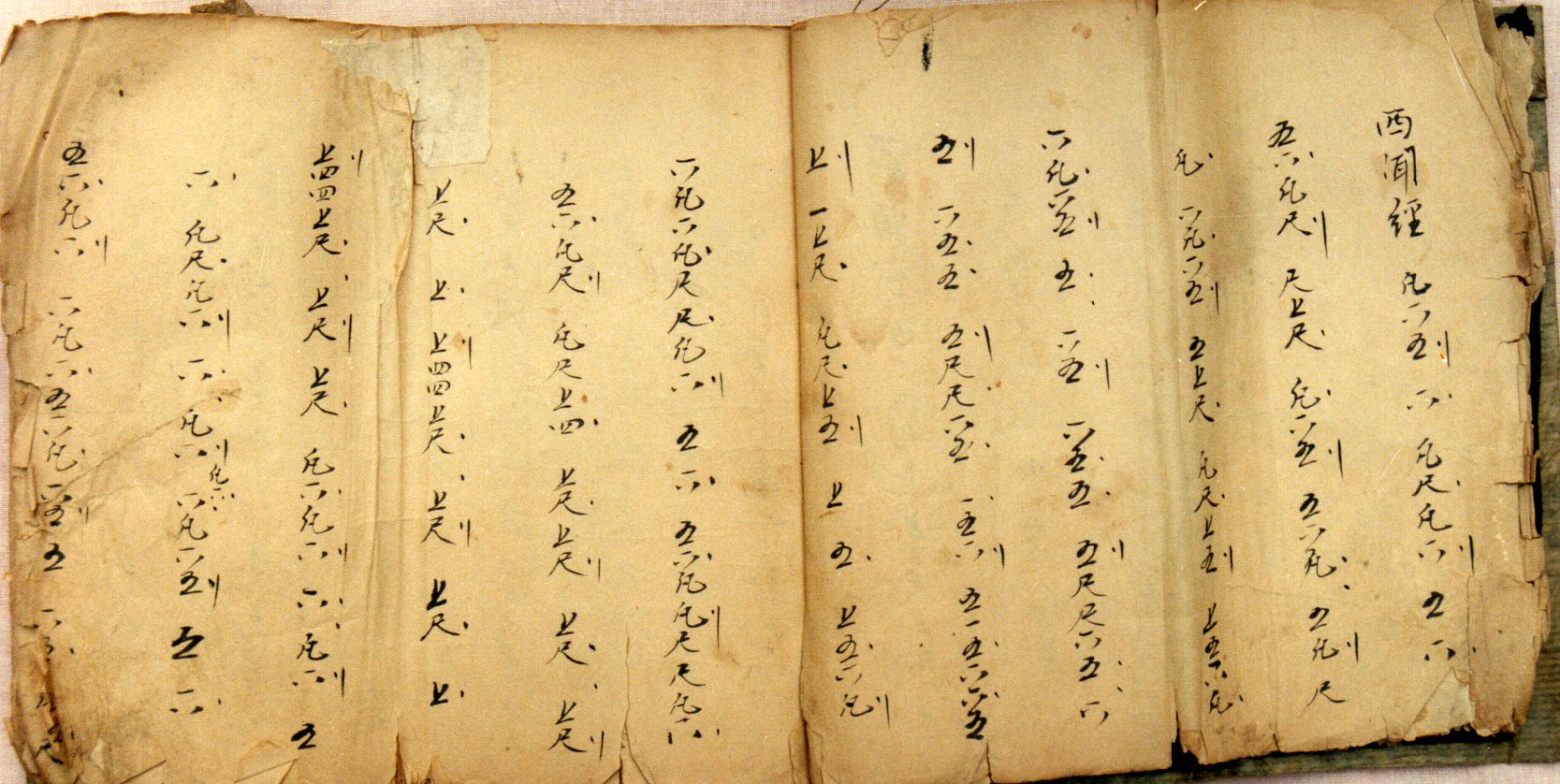

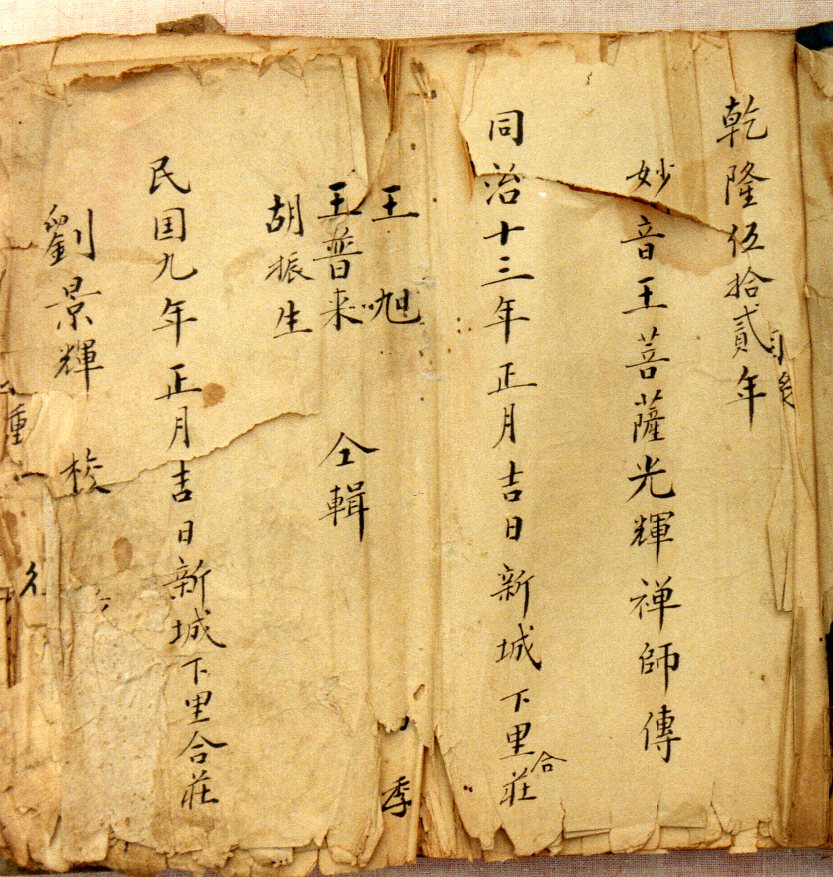

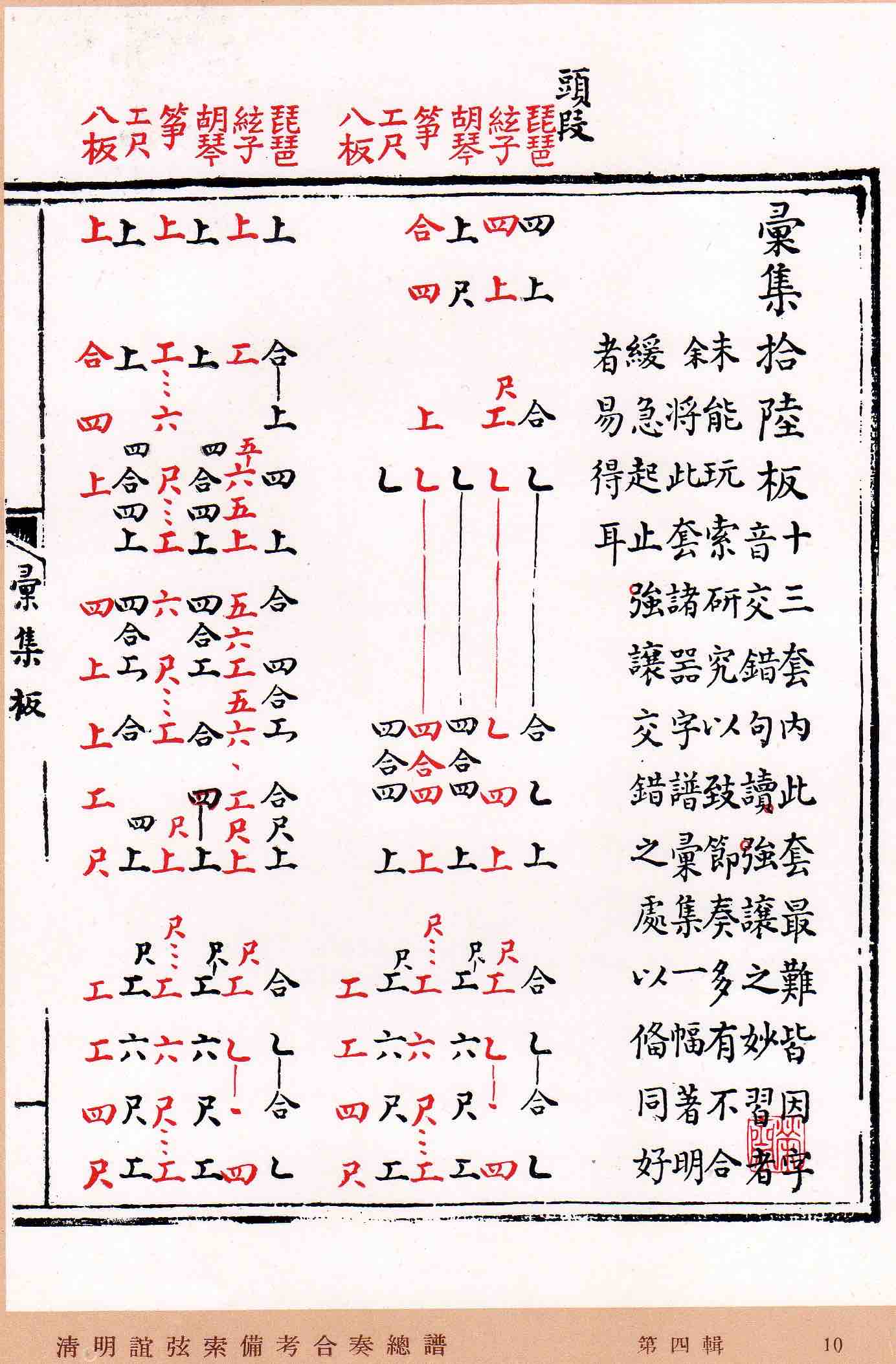

The Yuepu bian team, 2017. Gongche score, West An’gezhuang village,

Gongche score, West An’gezhuang village,  Ghost King,

Ghost King,  Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

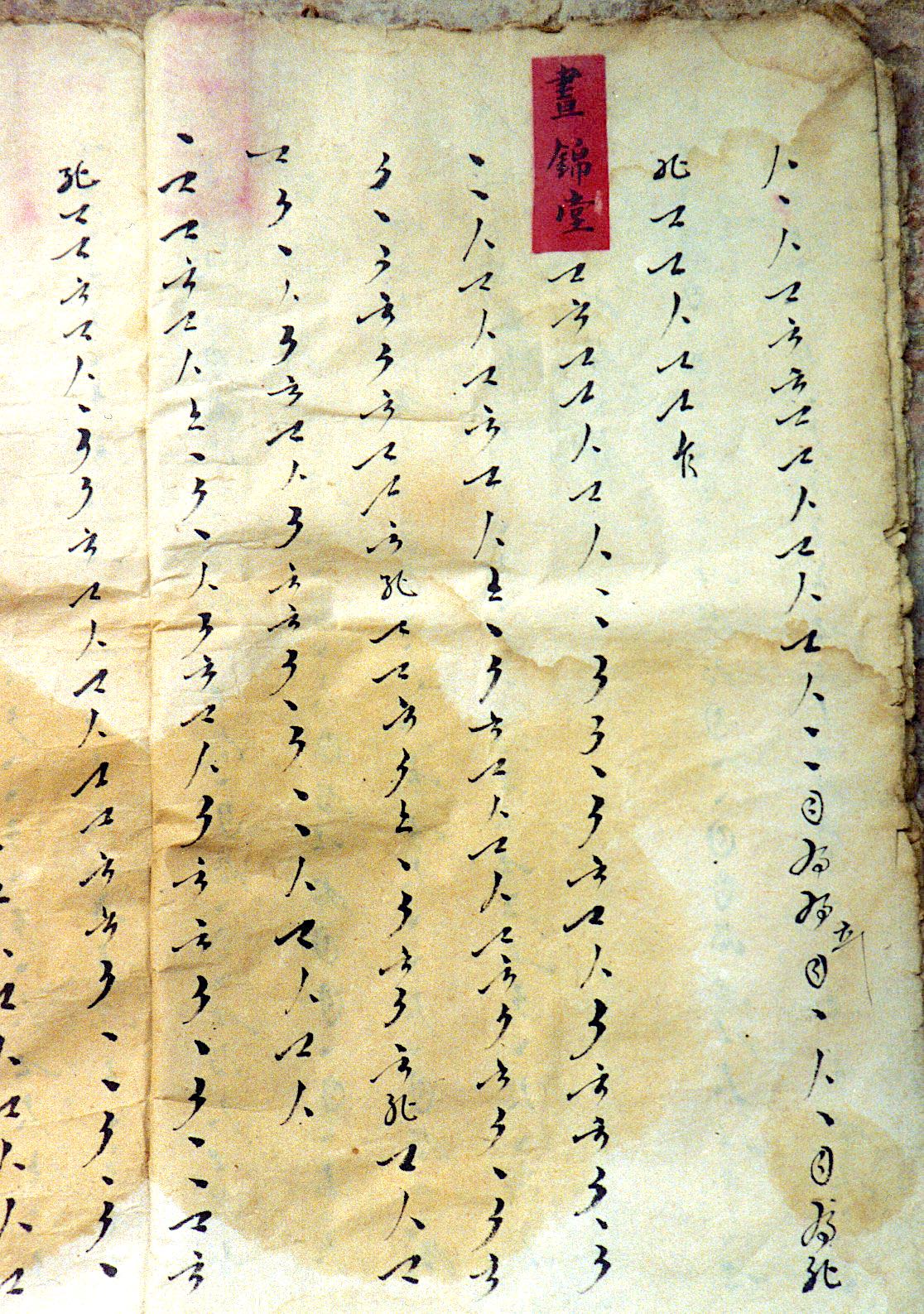

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

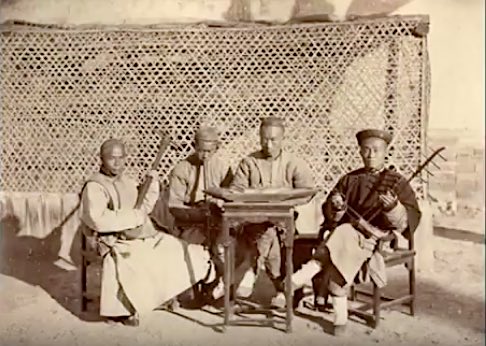

Shifan band, 1930s.

Shifan band, 1930s. Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).

Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).

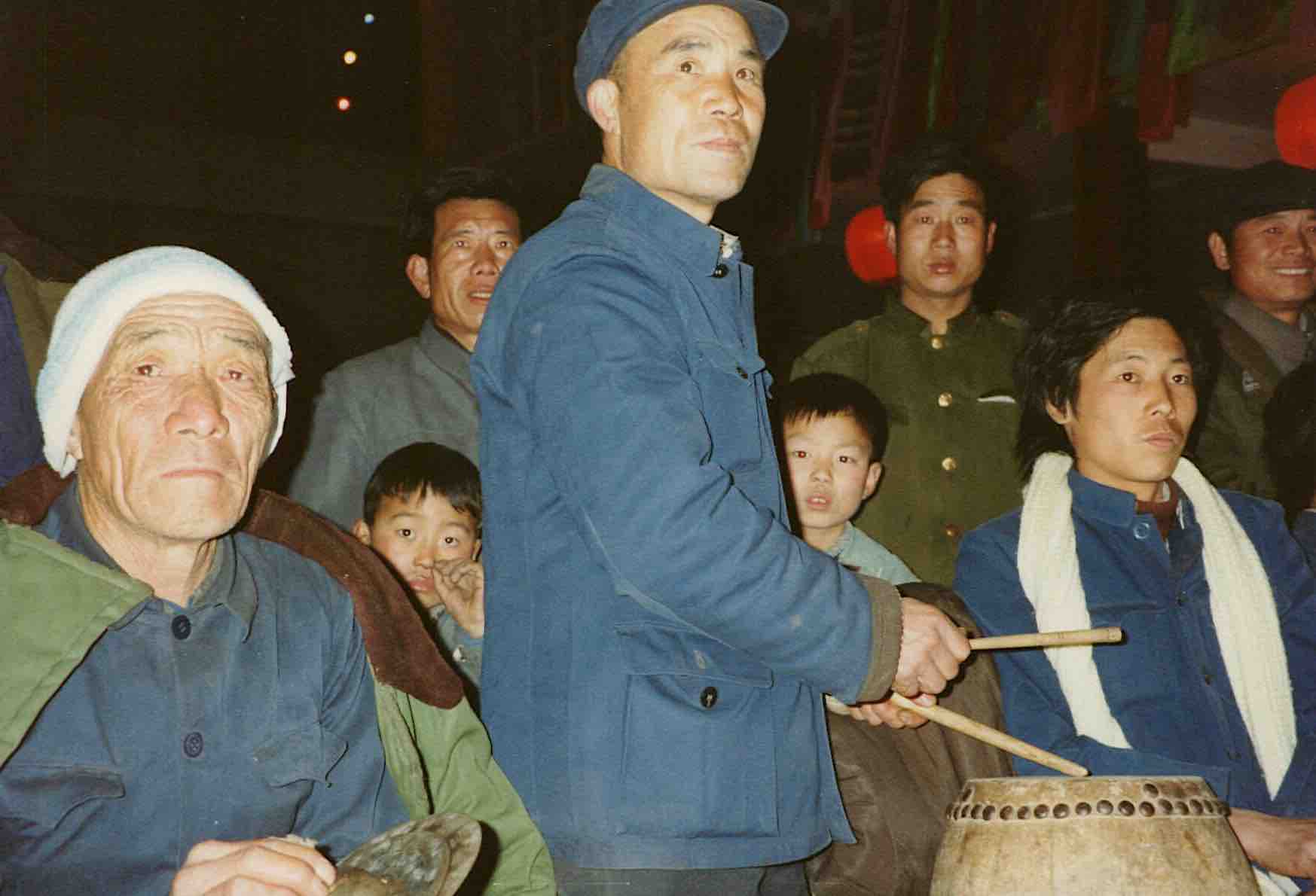

Some association members.

Some association members.

So I’m grateful to the exhibition for stimulating me to revisit some of my own material from the field. In this I’m always in awe of the incomparable erudition of

So I’m grateful to the exhibition for stimulating me to revisit some of my own material from the field. In this I’m always in awe of the incomparable erudition of

This reflects another common difficulty: we often seek to document history through major, exceptional events, whereas for peasants customary life is more routine. And apart from artefacts, much of the history of this (or any) period lies in oral tradition—which doesn’t lend itself so well to exhibitions.

This reflects another common difficulty: we often seek to document history through major, exceptional events, whereas for peasants customary life is more routine. And apart from artefacts, much of the history of this (or any) period lies in oral tradition—which doesn’t lend itself so well to exhibitions. From

From

From Qing-dynasty Tianjin Tianhou gong xinghui tu 天津天后宫行會圖.

From Qing-dynasty Tianjin Tianhou gong xinghui tu 天津天后宫行會圖.

Mural (detail),

Mural (detail),

This detail is particularly fine:

This detail is particularly fine:

For more recent Uncle Xi pinups, and incentives to display them, see

For more recent Uncle Xi pinups, and incentives to display them, see