Echoes of the past: refuge and memory, 1

Refugees, 1945.

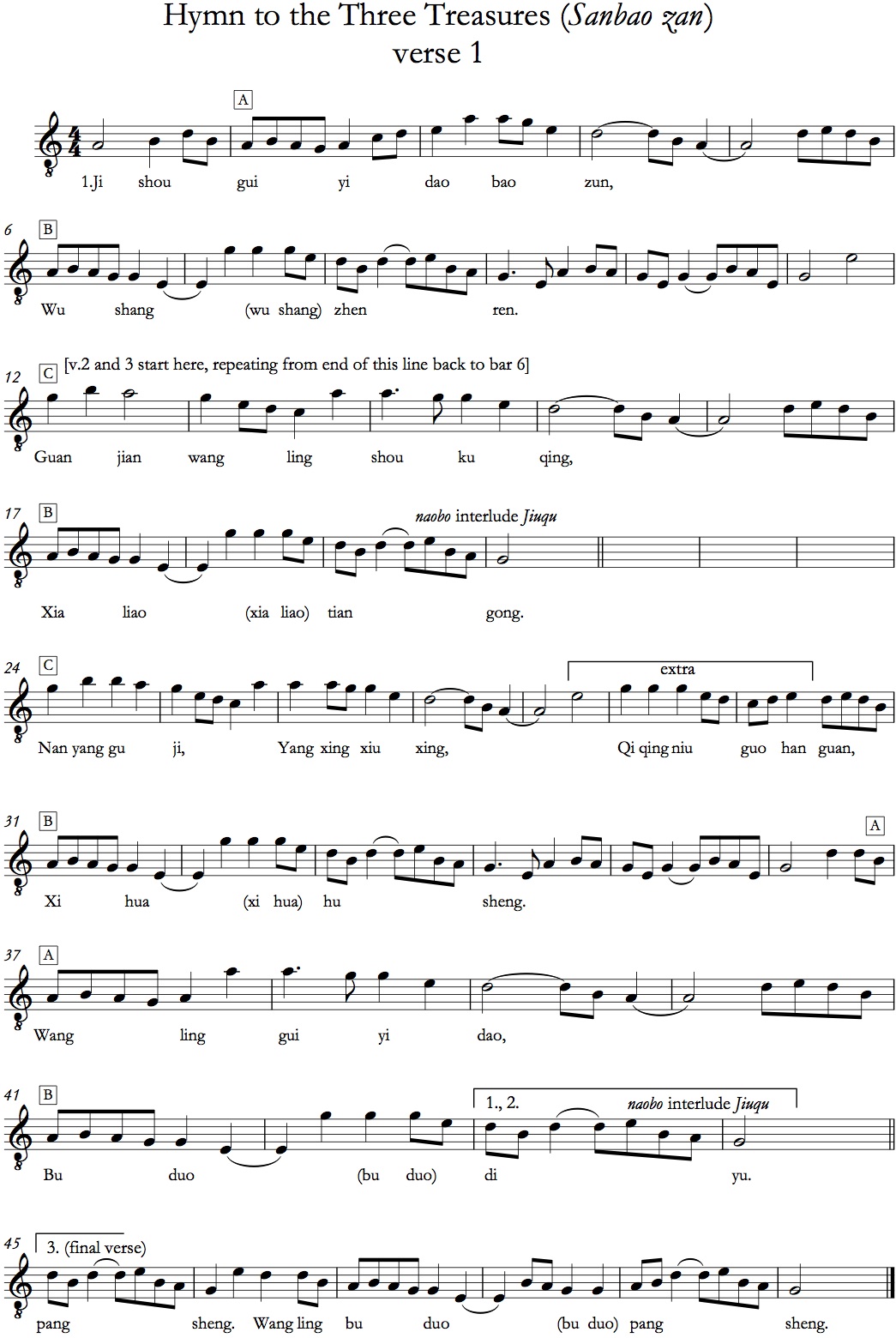

Hildburg Williams is a long-serving and popular violinist in London chamber and early-music orchestras, who has latterly added a major string to her bow [1] by becoming a distinguished German-language coach for singers in opera, lieder, and oratorio repertoires.

I’ve known Hildi since 1982, when we were playing a Handel opera in Lyon with the English Baroque Soloists under John Eliot Gardiner. Though I worked with her on and off for the next eighteen years (mostly in EBS), somehow we never managed to have a proper chat. As is the way with orchestral life, we moved in different circles, different groups going off in search of restaurants, and she was rarely to be seen in the bars that my mates frequented after gigs.

So I knew nothing of Hildi’s early years, fleeing twice from war and trauma; or the tale of her sister, who stayed behind in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Their stories are just a drop in the ocean of the continent-wide migrations in the period immediately following World War Two, not to mention more recent ones from farther afield—many such accounts have been published. But only very recently have I realized how important it is to tell the stories of such “migrants”; and this also bears on the post-traumatic amnesia that took hold not only on both sides of the German divide, but throughout Europe (including the UK)—and indeed China. All these lives are precious. [2]

After a couple of long sessions together, and some background reading, I produced a preliminary draft. Meanwhile, as Hildi was stimulated to reflect further on her life, more and more memories came to the surface, prompting her to give a more comprehensive account of her life—for her own sake, not merely at my behest. This, the first of two instalments, is my own adaptation of her story.

Chatting belatedly with Hildi has made an intriguing contrast with my main experience of fieldwork since 1986—making notes while hanging out with chain-smoking Chinese peasants between ritual segments at funerals. But the principle is rather similar: to document and empathize with people’s experiences through troubled times. Still, whereas in China my clear outsider-status somehow makes such talks quite smooth (though note my comments on “stranger value”), in this case, being somewhat closer I sometimes feel more impertinent. So it reminds me that we foreign fieldworkers intrude too blithely into the personal lives of our subjects—a privilege that is hardly earned.

Thankyou, Hildi—and a belated happy 80th birthday! Having boldly offered Stephan Feuchtwang some Bach for his own 80th, this tribute will at least be less aurally challenging.

Early years: Silesia

Hildburg was born in November 1937, the youngest of three siblings, in the town of Weißwasser in the Sorbian enclave of Upper Lausitz, east of Dresden—right by what is now the Polish border. The family ancestry can be traced back to Lower Silesia—her grandparents and parents originally lived in Bunzlau (now Bolesławiec, in Poland).

Both of Hildi’s elder siblings were born there, but by the time she was born the family had moved west to Weißwasser, where her father had been appointed as Rektor, school headmaster.

Hildi’s mother was also a teacher, but had to resign when she got married, as was the ruling in those days. However, when the war broke out she was reinstated. A young woman lived with the family, looking after the children.

Germans had made up the great majority in Silesia for many centuries. Weißwasser was just west of the Oder–Neiße line, which was to remain German even after 1945.

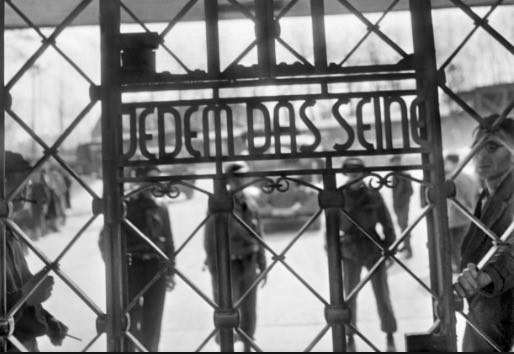

Through the 1930s the Jewish populations of such communities were ever more vulnerable. When Hildi was barely a year old, anti-semitic violence escalated with Kristallnacht; near Weißwasser, the Jewish population of Görlitz was among those targeted. In October 1939 a camp just south of Görlitz, originally for Hitler Youth, was modified into a PoW camp and began to receive inmates. Indeed, it was at this very camp that Messiaen, captured at Verdun in 1940, was interned—soon to compose and perform his amazing Quatuor pour la fin du temps there, as if untouched by human society.

By 1939 Hildi’s father was in his forties; in August, as the war started, he was called up by the Wehrmacht, going on to serve in the army administration in Poland, Russia, and France. Hildi reflects:

I can only remember one short visit when he was on leave. Apart from this, I only knew him from photographs and his letters home, which would often include little paragraphs to us children, with some drawings. [3]

But after the war he hardly talked about his experiences, so Hildi knows very little of this period in his life.

When she began attending school in 1943, her mother was her first teacher there (“a fact she enjoyed more than I”)—Hildi remembers addressing her in the third person like all the other pupils in class, anxious to fit in and not be treated differently from her classmates.

Up to the summer of 1943 the family spent the holidays at Hildi’s grandparents’ home in a little village just outside Bunzlau—they owned the former village school, with its large garden and a wooded area known as The Park. For the children it was an idyllic setting.

First flight

As we chat over coffee and cake in Hildi’s gemütlich little house in north London, I struggle to imagine the utter devastation of Germany by that time, evoking the most appalling images we have seen from Syria in recent years—and refugees then were just as vulnerable as Syrians today, desperately trying to survive by fleeing. Keith Lowe tellingly sums up the devastation of post-war Europe: [4]

Imagine a world without institutions. It is a world where border between countries seem to have been dissolved, leaving a single, endless landscape over which people travel in search for communities that no longer exist. There are no governments any more, on either a national scale or even a local one. There are no schools or universities, no libraries or archives, no access to any information whatsoever. There is no cinema or theatre, and certainly no television. The radio occasionally works, but the signal is distant, and almost always in a foreign language. No one has seen a newspaper for weeks. There are no railways or motor vehicles, no telephones or telegrams, no post office, no communication at all except what is passed through word of mouth.

There are no banks, but that is no great hardship since money no longer has any worth. There are no shops, because no one has anything to sell. The great factories and businesses that used to exist have all been destroyed or dismantled, as have most of the other buildings. There are no tools, save what can be dug out of the rubble. There is no food.

Law and order are virtually non-existent, because there is no police force and no judiciary. In some areas there no longer seems to be any clear sense or what is right and what is wrong. People help themselves to whatever they want without regard to ownership—indeed, the sense of ownership itself has largely disappeared. Goods belong only to those who are strong enough to hold onto them, and those who are willing to guard them with their lives. Men with weapons roam the streets, taking what they want and threatening anyone who gets in their way. Women of all classes and ages prostitute themselves for food and protection. There is no shame. There is no morality. There is only survival.

For modern generations it is difficult to imagine such a world existing outside the imaginations of Hollywood script-writers. However, there are still hundreds of thousands of people alive today who experienced exactly these conditions—not in far-flung corners of the globe, but at the heart of what has for many decades been considered one of the most stable and developed regions on earth.

By 1945, Silesia was ever more lawless. As German defeat was imminent, and with zones of occupation constantly shifting, the American and British inmates of the Görlitz PoW camp were marched westward in advance of the Soviet offensive.

On 17th January 1945 what was left of Warsaw was “liberated”; Krakow and Lodz soon followed. Budapest fell to the Soviet forces on 13th February; and as they were closing in on Berlin, Dresden was obliterated by RAF bombs on 13th–15th February.

There was still desperate fighting (see also here) around the Silesian region in April. The 1st Ukrainian Front captured Forst on the 18th. As Hildi recalls:

I remember our last days in Weißwasser vividly—the food shortages, the frequent air raids, the sound of fighting, the endless treks of refugees fleeing westward passing along our street. Every night my mother would take a family in to give them food and a bed before they continued their journey the next morning. The raids intensified daily and on the 13th February the light from the burning Dresden was clearly visible. As the fighting drew nearer, we could hear the bombardments coming from Forst just north.

During these anxious days there was a young woman briefly lodging in the flat who was betrothed to a German lieutenant. He told her she should urge Hildi’s mother to leave. The last military train going west was due on the 19th February from Hoyerswerda, 7 kilometres from Weißwasser. So along with a throng of desperate people (mainly women, children, and the elderly, since most men were either dead or away fighting), they now fled their home. Hildi, then seven, vividly remembers the chaos, with refugees panicking as they fled in all directions.

The most essential items were hastily packed, and I still remember gratefully that I was allowed to take both my beloved dolls. The lieutenant sent his orderly with an open lorry for us to catch the train—which turned out to be already overcrowded with hardly any room. My sister was precariously perched on top of several suitcases, resting her feet on the handle of a pram.

The train eventually left the next morning, but even on the night before there was an air-raid. Some people panicked and fled, but luckily the train was not hit. The journey was agonizingly slow, with the train frequently grinding to a halt. At some stations it was possible to get some soup and a hot drink, but these were dangerous moments, as nobody knew how long these stops would last and people were afraid the train might set off without them.

Planning to get to the small town of Kahla, near Jena in Thuringia, to stay with the family of an uncle, Hildi’s family finally climbed out of the military train in Zwickau, embarking on several complicated train changes. Again the carriages were packed with huge numbers of other refugees and luggage, so sometimes people could only get off the train by clambering out of a window. It was snowing and the ground was covered with dirty slush.

Thuringia, 1945: brief US occupation

When after three days they at last reached their destination, Hildi’s aunt gave them the use of one room in her flat, with the children sleeping in a little attic room. But even here they found that far from being safe, escalating air raids meant spending anxious hours in the cellar huddled together with the other occupants of the house.

Communication was sporadic: there were disruptions everywhere, with large sections of the railway lines destroyed (at the end of the bombardment only 650 of 8,000 miles of track were operating), and so any letters that made it through were long delayed. With millions on the move, tracing the whereabouts of family and friends proved arduous.

The family did at least have a little radio, and Hildi was delighted when a broadcast of a classical concert came on. Meanwhile, news broadcasts were less instructive than rumours of the allied troops’ advance, which created great anxiety.

American forces began occupying the province of Thuringia from 1st April; Patton’s forces entered Buchenwald on the 11th (for my post on Ravensbrück, see here).

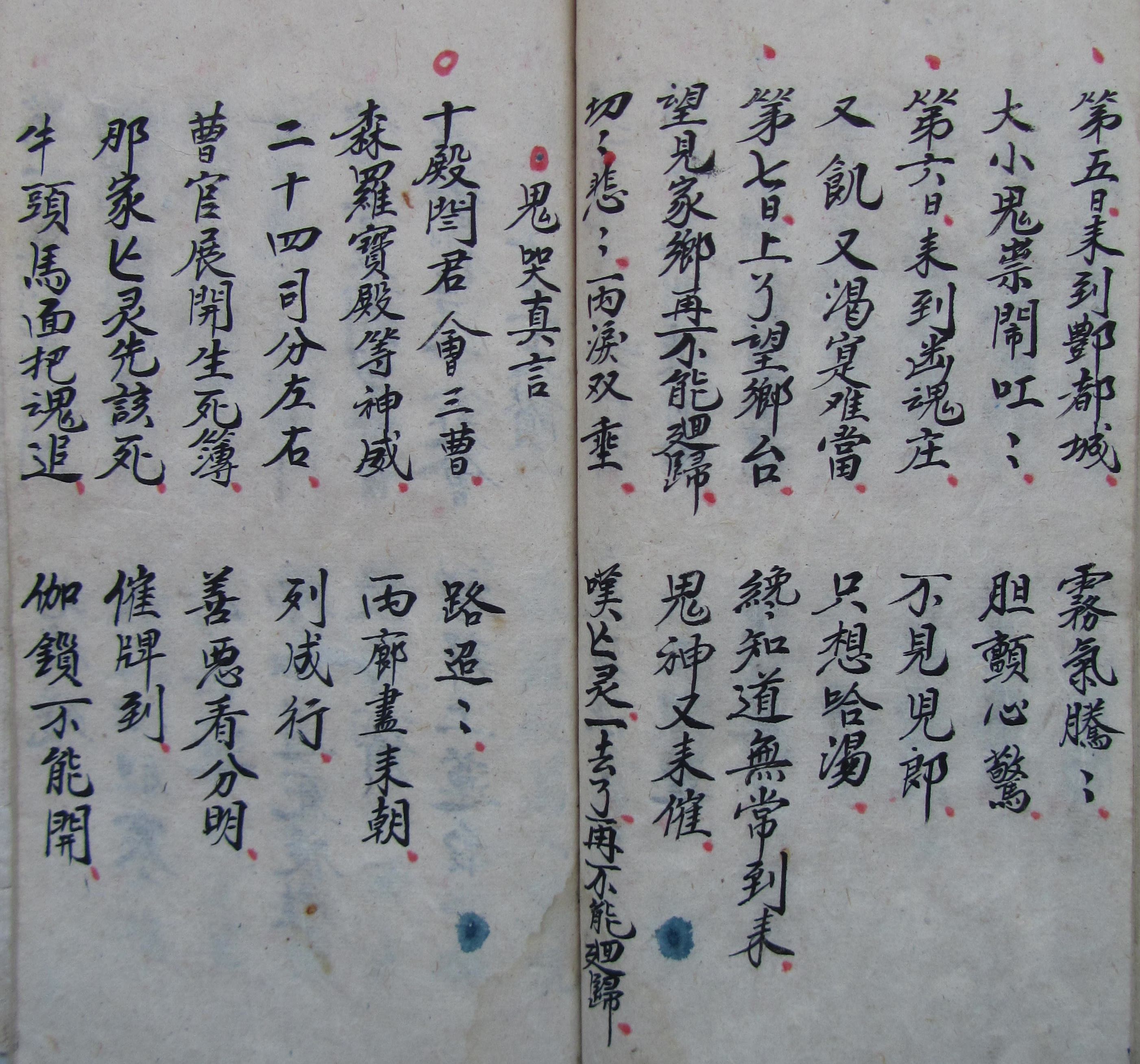

Dresden in ruins.

On 20th April the Russians reached Berlin. As agreed by Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin as early as 1944, and confirmed at the Yalta conference in February 1945, the defeated Germany (including Berlin) was to be divided into four zones of Allied occupation. Thuringia was to belong to the Soviet zone, but the Americans arrived there first before the fighting ended. Hildi’s family had no inkling of all this until later.

In Kahla, the situation deteriorated dramatically early in April, just after Easter, with frequent air raids. In a last-ditch effort, the German forces blew up the bridge over the river Saale. Warplanes were flying low over the town, with bombs exploding alarmingly close.

We seemed to spend most of our time in the cellar, anxiously listening and waiting for the all-clear signal, and then, climbing upstairs again, being thankful that, for now at least, we had been spared.

Then the day came when, with a roar of heavy motorcars and tanks, the Americans announced their arrival. Cautiously peeping through the windows, we saw the whole street full of cars and jeeps, which were constantly washed and polished.

The GIs went from house to house to find accommodation for their people. Nearly all the houses in our street had to be evacuated, but ours was spared. When the GIs came to investigate it was lunchtime, and our large family was sitting around the kitchen table—my mother, my aunt, my grandparents (who had recently arrived from Silesia by trek), and we children. When one man in uniform asked: “How many children?”, my mother answered in English “Five”, whereupon they left.

We mainly stayed indoors—there was a curfew in place, and at first only two hours were allowed daily for people to try and get provisions from shops, where there were long queues. On 2nd May ration cards were introduced, and the electricity supply seemed to be becoming more stable, but sadly, one day our radio was confiscated. From now on we could only get snippets of news while queueing for food. News of Hitler’s suicide on 1st May, and the signing of the act of surrender on the 7th, was anxiously passed around. We children picked up the atmosphere of doom and desolation.

Hildi recalls the GIs:

It was the first time in my life I saw a black person. I had heard that these were the people who were kind to children and were known to give them sweets and chocolate. So one day I plucked up my courage and gingerly approached one of them, uttering my first English words—“Have you chocolate?” I had never tasted chocolate—whenever I asked about it I would always get the answer: “When the war will be over”, to which I would wearily reply: “This is always your excuse!” Now the war really was over, this seemed to be the moment—but the soldier, somewhat bewildered, just shook his head.

At first the officials of the American Military Government were under strict orders to treat the defeated population with stern discipline. Rations began to shrink, often to under 1,000 calories per day. My mother lost so much weight that one day she was blown over by a gust of wind, spilling the precious thin broth she had just acquired from the butcher after queueing for ages. The black market flourished, but as refugees neither my mother nor my grandparents had anything of value to offer. Food shortage was a constant problem, but somehow they managed to put something on the table.

Under Soviet occupation, 1945–49

However, Thuringia was only to be very briefly within the US zone; in a deal unbeknown to locals, as the Allies had agreed with the Soviets for part of Berlin, the American troops began withdrawing on 1st July, ceding it to the Soviet forces—precisely those that Hildi’s family had fled from the east to evade.

Then on 2nd July, without forewarning—almost overnight—the scene changed. The US jeeps disappeared, followed by an eerie, foreboding silence; and finally, as we all peeked anxiously through a small gap under the closed jalousie, Russian pony-driven carts arrived. What a change from the smart vehicles of the Americans! What a shock! What would become of us now?

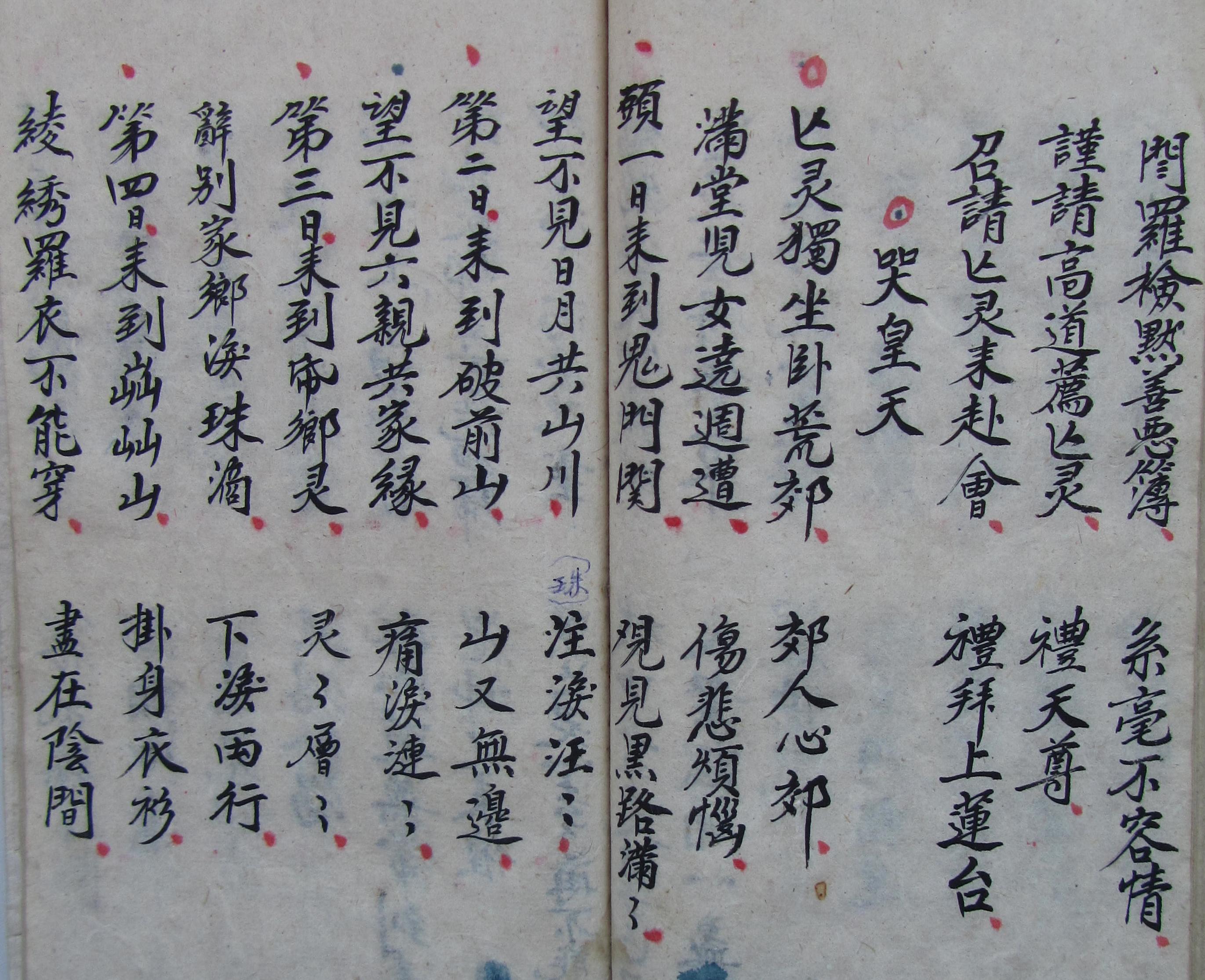

Russian troops passing GIs into Weimar, 4th July 1945.

For the time being, having only just escaped the east with such difficulty, Hildi’s family stayed put. They were now to live under the Russian regime until 1948, when the administration began to transfer to what in 1949 became the GDR.

Still, Hildi’s family had done well to flee early from the east. Over three million people had fled west before the organized expulsions began, mainly driven by fear of the advancing Soviet Army; and another three million Germans were expelled in 1946 and 1947. For many, the formal end of the war was not an end to their suffering but a beginning; vast numbers died in the process.

As a post on armaments in the Kahla region comments,

The population’s fear of retaliation at the hands of the incoming Red Army resulted in a gigantic wave of German refugees. […] All through May, the American military witnessed the panicked streams of refugees heading west. In addition, there were masses of people from further east fleeing before the advancing Soviet troops.

Hildi reflects on my impertinent queries asking if they now considered taking flight from the Russians once again in July 1945:

In July 1945 the whole of Germany was in total chaos. Everyone was solely occupied with survival—there was no time for reflection, still less for coming to terms with the past. While travel was still possible, not only were journeys arduous and complicated, with the rail network still in disarray, but where should we go?

The housing situation was dire. Apart from the millions of refugees from the East, there were all the survivors of the bombings, now homeless, who had to find a roof over their heads as most cities lay in ruins. One couldn’t just turn up anywhere—one had to know someone who could guarantee at least some sort of accommodation. My mother’s youngest sister lived in the northwest, but she only had one room for herself—though she became an important point of contact for our entire family, at a time when so many people were desperately trying to locate their loved ones and friends, or simply to find out if they were still alive.

Above all, in 1945, apart from the zones of occupation, one was not yet conscious of a divide within Germany into “East” and “West”. The whole of Germany faced the same chaos of devastation, having to deal with the aftermath of war. Mountains of rubble had to be cleared—a task mainly performed by women, since their men were either still prisoners of war or too old and infirm to take part. [6] Everyone was living from one day to the next. With our large family including aged grandparents, there was no hope of resettlement in the near future. Besides, there was no indication then that life was any easier anywhere else.

Were we worried? I am sure the adults were. Were we safe? I think, on the whole, we were. Following the departure of the American forces, the Soviet soldiers were now on strict orders to behave accordingly, and were severely punished, often beaten, when they transgressed. Fraternization was strictly forbidden—there was a definite “them” and “us”. The hegemony of the occupying forces was never in question.

Considering the widespread punitive measures against Germans in these first few years after the war, and many horror stories, they were relatively unscathed. But as Hildi observes, hunger was still a constant companion, especially for city dwellers. In the villages, in the early days before farms were confiscated by the state, there was still enough produce; townspeople brought anything they could find of any value to exchange for food. It was said that the only thing missing at the farms were the Persian carpets in the cowshed!

Although we were given ration cards, the shops did not have enough supply, so wherever there happened to be a queue people would join, even if it was unclear what was for sale.

I remember our excursions to pick mushrooms in the woods nearby. We became quite knowledgeable about them. At home we would clean and slice them, threading the slices on a pieces of string to dry for the winter. We did that with apples too. Eventually we were given a small plot of garden, and my grandfather worked hard growing vegetables and salad. As living standards improved in the Allied zone, the highlights were occasional food parcels from relatives there with essential provisions—and to our delight they would sometimes even reveal a chocolate!

My older sister, now 17, helped enormously, working for a farmer in a village 7 kilometres away—not only could she now get enough to eat, but we had one less mouth to feed. On many weekends she would walk this long distance, carrying back as much food as she could manage.

After the harvest the townspeople were allowed to glean the fields. They would all line up at the edge of the field and only after the farmer had raked it over thoroughly was the sign given to enter. The stalks were gathered like a bunch of flowers before the heads were cut into a sack. Back home my grandfather would beat the sack until the husks separated, then blow them away carefully until he had just the grains in his palm. They were worth their weight in gold; some would be ground in an old coffee grinder to make porridge, and if there were enough then the local mill would exchange them for flour, a welcome supplement.

Occasionally slices of bark and pieces of wood were available from the local sawmill, which we piled up high on our rickety wooden cart. My grandfather then used an axe or a saw to cut them for our stove and wrought-iron oven. He also built a rabbit hut. We children loved these cuddly animals, and got quite upset whenever one suddenly went missing—my grandfather made sure we were not around when he sacrificed it for the pot.

Women had to be inventive with their dishes. I remember a brownish bread spread, ambitiously called Leberwurst, made from a flour mixture and spiced with marjoram, as well as Schlagsahne (whipped cream) made from whey, a thin greenish liquid that was available for free at the local dairy. For some time these recipes were carefully stored in a box, but, thankfully, never used later on! We children could not be choosy— we ate everything.

For cooking we had enormous pots in the kitchen, as the food lacked the necessary substance. Later they were adopted for boiling the washing.

Looking back now it seems amazing how we adapted to the deprivations of our daily life. Power cuts were frequent, and with candles in short supply we just stuck a piece of resin-wood into an earth-filled flowerpot and set it alight—a sooty affair! At other times we just sat in the dark and sang.

In 1945 Hildi’s father had been captured and interned in a PoW camp; [5] by June he was able to rejoin his family in Kahla. He must have known that his wife would try to get them away from Weißwasser, but with no means of telephoning, and only a sporadic postal service, Hildi doesn’t know how he found out where they had escaped to.

As Hildi’s father approached, pushing a bicycle, she was standing at the gate; recognizing him as he called out her name, she was so excited to see him that she jumped up to greet him and chipped a corner out of one of her front teeth.

Now at last we were a real family! My father immediately applied for a job. At a time when numerous factories were dismantled and their machinery taken away, he was lucky to find a job at the still-functioning sawmill. For a man who had never had done any physical work in his life, this was hard for him. There was no other footwear but heavy wooden clogs, and my mother spent hours sewing patches onto his torn gloves.

My brother and I spent the summer holidays of 1946 with our former help and her family in a village near Bautzen, east of Dresden. For my parents this was a godsend, since they could be sure we would be properly fed there; for us children it meant an exciting long train journey and a wonderful time in the country. But the journey confronted us with images that remain ingrained in my memory even today. Passing through Leipzig we witnessed with horror the devastation on both sides of the track—ruins everywhere, eerie monuments of gruesome battles, tall buildings sliced through the middle, with the occasional lone piece of furniture precariously balancing on the edge.

Leipzig devastated.

Just opposite their house was a school that served as a barracks; during this time another building was used for some teaching. So Hildi’s grandfather (himself a former teacher) gave her additional lessons, with daily reciting of maths tables. When the troops finally moved out, the barracks became a school again, which Hildi now attended. Among the subjects there was Russian, which she learned reluctantly. But she was much keener on learning the violin, taking lessons along with her brother from elderly local musician Emil Wittig—Hildi’s brother became his star pupil, and to this day she still treasures a copy of the Kreutzer violin studies with a dedication to him from their teacher.

If their radio hadn’t been confiscated, Hildi would have loved to hear broadcasts of the classics with conductors like Furtwängler. Here he is in 1948, rehearsing Brahms 4 in London—where his visits were still sensitive, since though acquitted of collaboration late in 1946 it would still be some time before he was entirely rehabilitated abroad:

Like Chinese people, Hildi’s father never discussed his war experiences—which, apart from perhaps being politically uncomfortable, must have been deeply traumatic.

Although we children seemed to find our own way through this period of deprivation, we could not help picking up the general atmosphere of resignation, uncertainty, and fear. Outside the home people did not engage in conversation before making sure no-one was nearby who could possibly listen. At school it was not uncommon for a teacher to use children as tools to gain vital information from them about their elders’ opinions. My brother and I were instructed never to mention any sensitive topics we might have heard at home.

By October 1949 Hildi’s family found themselves part of the new German Democratic Republic (GDR).

Apart from the major trials of the worst culprits, de-nazification [7] was pursued patchily even in the first couple of years after the war, as the occupiers soon discovered it was both impracticable and undesirable; in the Allied zones, reconstruction took priority over principles as Cold War loomed. People heard about the war-crimes trials, but they were little discussed, and never part of the school curriculum.

Discretion became still more important when in 1949 Hildi’s father planned to cross the border to Westphalia in the British zone, hoping to find a new life in the West so the family could join him eventually. His parents-in-law had already made the journey earlier without too many problems, since “old people” were considered not just unproductive but a burden on the state.

Sure enough, after a long trek northwest Hildi’s father managed to reach Detmold, where he was offered the use of a hut in a large garden belonging to a friend of a friend. At once he found work as a gardener, later getting an office job with the British authorities.

With the de-nazification process now inevitably something of a formality, it was formally abolished in 1951 with the ponderously-named Entnazifierungsslußgesetz law (expanding my acquaintance with German polysyllables). Meanwhile, senior German conductors jumped through the requisite hoops as the new authorities pored over their careers under Hitler. The search for culprits still continues even today, but there was no call for repentance, and nothing resembling Truth and Reconciliation—either here or later in China.

In Kahla, Hildi’s mother was questioned twice about her husband’s whereabouts by two officials knocking on the door. She simply replied, “He has abandoned us. I have no idea where he is.”

Second flight

In March 1950 Hildi, with her mother and brother, managed to flee the new GDR to join her father. But this time her sister made the choice to stay behind. Her life had changed for the better in 1947, when she was accepted for the pedagogic school for mathematics and natural science in Gera, east of Kahla. In what Hildi observes was a strange way of beginning one’s studies, all the students had to take part in clearing the Thuringian forest, sawing and stacking felled tree trunks—at least they were allowed to take some wood home.

By 1948 Hildi’s sister had a diploma, and soon found a teaching post. She realized her qualifications would count for nothing in the Allied zones, and she couldn’t face having to retrain; and besides, she had fallen in love with her future husband. The family parting was difficult.

After the trauma of their original flight as part of a mass exodus west in 1945, this second journey posed different challenges.

Our preparations for escape were complicated. The few belongings that we had gradually accumulated needed to be sent ahead in parcels. This was not officially allowed, but we had found one guard at the station who would turn a blind eye and post them. If he was not on duty, which was often the case, we just had to turn back home again with our wooden cart laden with parcels, and try our luck another day.

Just such a cart is an iconic image of the refugee exodus, displayed in museums like the excellent Forum of Contemporary History in Leipzig:

Finally we set off on the hazardous journey across the Harz mountains, by the same route that my father had taken. I was now 13. With the help of a guide, a woman who knew which route to take and was familiar with the schedules of the border guards, we made our way with rucksacks on our backs, my brother and I clutching our violins. At the time there was still movement in both directions, but since trains were rigorously searched at the border, a whole family travelling west would have aroused suspicion. So we got off one stop before the terminus and climbed down the railway embankment. Crouching at the bottom of it, we waited anxiously until the train set off again. It was already dark. Then started a long and difficult walk. Our nerves at breaking point, no-one spoke. We watched our footsteps, carefully avoiding the dry leaves on the ground. Occasionally there would be a rustle—our heartbeats racing, we all stopped and held our breath. But often it was just someone returning from the West, going in the opposite direction. The journey seemed endless, but at last we made it!

So after a trek of two days they once again found refuge, reunited with Hildi’s father in Detmold.

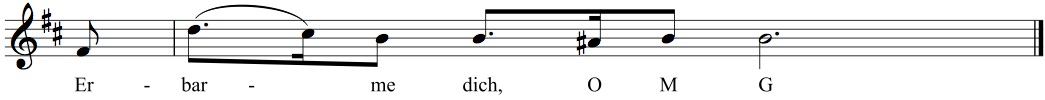

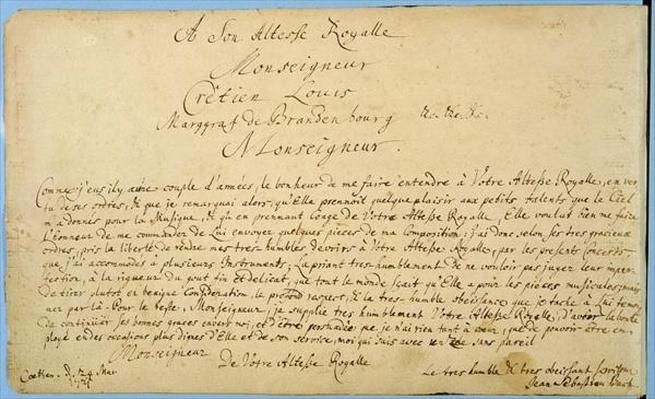

Given Hildi’s later immersion in Bach, her trek has an interesting parallel with Bach’s Long March from Thuringia to Lübeck in 1705 to seek his hero Buxtehude—in very different circumstances, and even further, over several months.

Meanwhile in rural China, the Li family Daoists, having mostly survived the Japanese occupation, were soon plunged into civil war and the turmoil and violence of “Liberation”—somehow continuing to provide ritual services for their local community throughout the whole period. All over the world convulsions continued in the wake of war, with over a million dying in the Partition of India.

Nearly four decades later, as we sat together in orchestras playing Bach and Handel, I had no inkling how very stressful Hildi’s early experiences were. In the next instalment we follow her from Westphalia to Zurich, and then on to London, as she embarks on a life of music; and we reflect further on refuge and memory.

[1] Sic: the metaphor is from archery, not fiddles, of course.

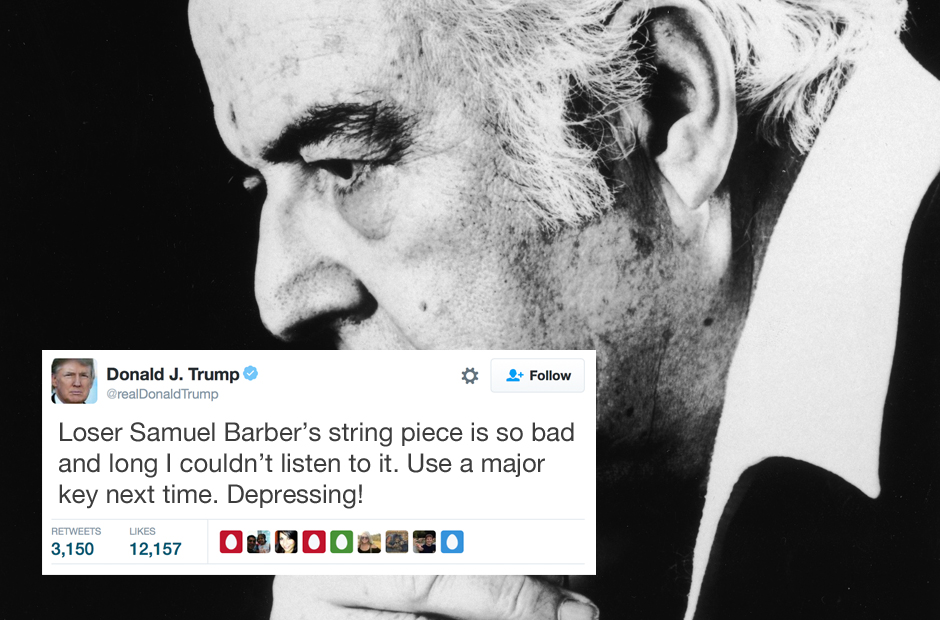

[2] Whatever the Daily Mail, or the Putrid Tang Emanating from the White House, may tell us. Among many documentaries on the current plight of refugees, the BBC series Exodus is remarkable.

[3] Cf. Hester Vaizey, Surviving Hitler’s war: family life in Germany, 1939–48.

[4] Savage continent: Europe in the aftermath of World War II, pp.xiii–xiv; I find this book a most instructive and sobering introduction to the period right across Europe. I can barely scratch the surface of the vast literature on the immediate post-war period. Other accessible books include Giles MacDonogh, After the Reich, and Frederick Taylor, Exorcizing Hitler—where the appalling situations in Silesia and Thuringia can also be pursued. Moving and detailed is Gitta Sereny, The German trauma.

[5] For the desperate conditions of the PoWs, see MacDonogh, ch.15; Taylor, pp.173–87; Lowe, ch.11.

[6] See also MacGregor, Germany: memories of a nation, ch.27.

[7] MacDonogh, pp.344–57; Taylor, chs. 10–12, and Epilogue (for the Soviet zone, see pp.323–31, 360–61).

Glorious is the Earth

Glorious is the Earth