They come over ’ere…

On the recommendation of Satnam Sanghera’s Empireland, I’ve been reading

- Robert Winder, Bloody foreigners: the story of immigration to Britain (2004, with new chapter for the 2013 edition).

As I write, it’s a horribly topical theme—but it always is (for Winder’s thoughts on this month’s riots, click here).

Immigration has always been a “nuanced and uneven affair”. Migrants are diverse; loyalties can be fluid and overlapping. While Britain has a chronic history of race riots, social unrest has varied. But “the political language remains morose”, irrational—venting prejudice rather than debate. Emigration “strikes us as daring and sprightly […] yet we habitually see immigrants not as brave voyagers but as needy beggars”. Britain has been both resistant and accommodating, with successive assimilations, new prejudices, routine kindness, and adaptability. Besides all the unsung workers who keep the economy afloat, immigration has long invigorated our institutions, architecture, music, literature, and our very language; “immigration is a form of enrichment and renewal”. But Bloody foreigners is no naive celebration; of course it’s a plea for tolerance, but Winder offers no simple solutions.

Even in recent times (in the war-inspired propaganda of the 20th century, for instance) we have cultivated a belief in Britain as unconquerable; mighty forces such as the Spanish Armada, Napoleon’s war machine, and the Luftwaffe, we told ourselves, failed to breach our ramshackle but resolute defences. This indoctrination has left a false but distinct impression that we have never been invaded. Indeed, the famous insularity of the British is often attributed to the fact that we do not, unlike our continental friends, have a folk memory of foreign occupation. But this means only that our memories are short and unreliable, because our early history is one of little else.

On the eve of the Norman conquest,

What we now think of as the archetypal English character was already, at this early stage, a robust mixture of Mediterranean, Celtic, Saxon, Roman, Jute, Angle, Danish, and Norwegian, all moulded and rain-streaked by the British climate and landscape.

Traders, craftspeople, entrepreneurs, artisans, and heretics all began finding a home in Britain, and were resisted. Among many disturbances, what Winder describes as a “race riot” erupted in Norwich in 1312, attacking foreign traders, mainly Flemish and Walloon weavers. Chapter 3 relates the prospering of the Jews and pogroms leading up to their expulsion in 1290—“both a tragedy and a national disgrace”. Chapter 4, “Onlie to seek woorck”, tells how migrants filled a gap in the labour market left by the 1348 Black Death. Gypsies arrived from around 1500, also suffering discrimination. By this time there were 3,000 foreigners in London, 6% of the civic population. In towns like Sandwich and Canterbury as much as a third of the population were immigrants, both bringing prosperity and causing antagonism.

The luckless foreigners incurred the wrath of the locals in two contrasting ways: they were hated if they became rich, and even more if they remained poor. If wealthy, they were gimlet-eyed exploiters; if starving, they were good-for-nothing trespassers.

Concluding a section on the Jews who found a haven from the 1648 pogroms in Ukraine, Winder has a prophetic comment:

In its bumbling way, England was providing a precious sanctuary for those persecuted in brasher countries. Soon however, this newfound tolerance would be tested on a scale never before imagined.

French Huguenots:

Left, refugees landing at Dover in 1685, engraving by Godefroy Durand, 1885 (source).

Right, Hogarth, Noon, 1736 (source)—

Winder’s caption: “Affluent Huguenot churchgoers tiptoe past the ill-kempt natives”.

Huguenots (one of the most inspired vignettes in Stewart Lee’s debunking of UKIP! cf. Rachel Parris) had fled persecution after the 1572 St Bartholomew’s Day massacre, but the main influx began from the late 17th century. Along with their expertise in making clothes, hats, paper, pins, needles, watches, clocks, and shoes, they possessed financial and mercantile skills. [1] The Huguenot merchants

probably thought of themselves as working temporarily from the London office. The rest were waiting for civilisation to return to France so that they could go home and pick up the threads of their former lives. This is true of a great many immigrants, even today. Immigration, indeed, might be a rather grandiose unequivocal word for what is often a diffident decision, full of hesitations and reluctant compromises. The drip-drip process of acclimatisation becomes immigration only in retrospect. […]

The Huguenot exodus was torrid, and only with the benefit of several hundred years’ distance can it strike us as inspiring. But from that vantage-point we can hardly deny that they came, saw, and prospered. Nor that “we”, after a certain amount of bluster and some clenched-fist bitterness, in the end accepted them without much more than a murmur.

Under the Hanoverian empire (George I, “most important immigrant of the 18th century—according to the traditional definition of what counts as important”), Germans came to Britain to work as businessmen and artisans; German architects, playwrights, and musicians played a major role in our cultural life. Migrants arrived from Holland, France, Poland, Italy, and the British colony of India; the population of Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews kept growing.

Chapter 9, “Servants and slaves”, describes the African slave trade and its immense profits—a story of coercion that contrasts with the choices of previous generations of immigrants.

18th-century England was home to several thousand Africans who carried messages, steered horses through crowds, cooked, swept, busked, scrimped, saved, gambled, drank, slipped into secret doorways, clenched their teeth and cowered in fear, all in plain view of so-called polite society. Most social histories of the period see it as a time of elegant country houses, […] a neoclassical arcadia, in short, shot through with bolts of sexy exuberance, gluttony, and inventive industry.

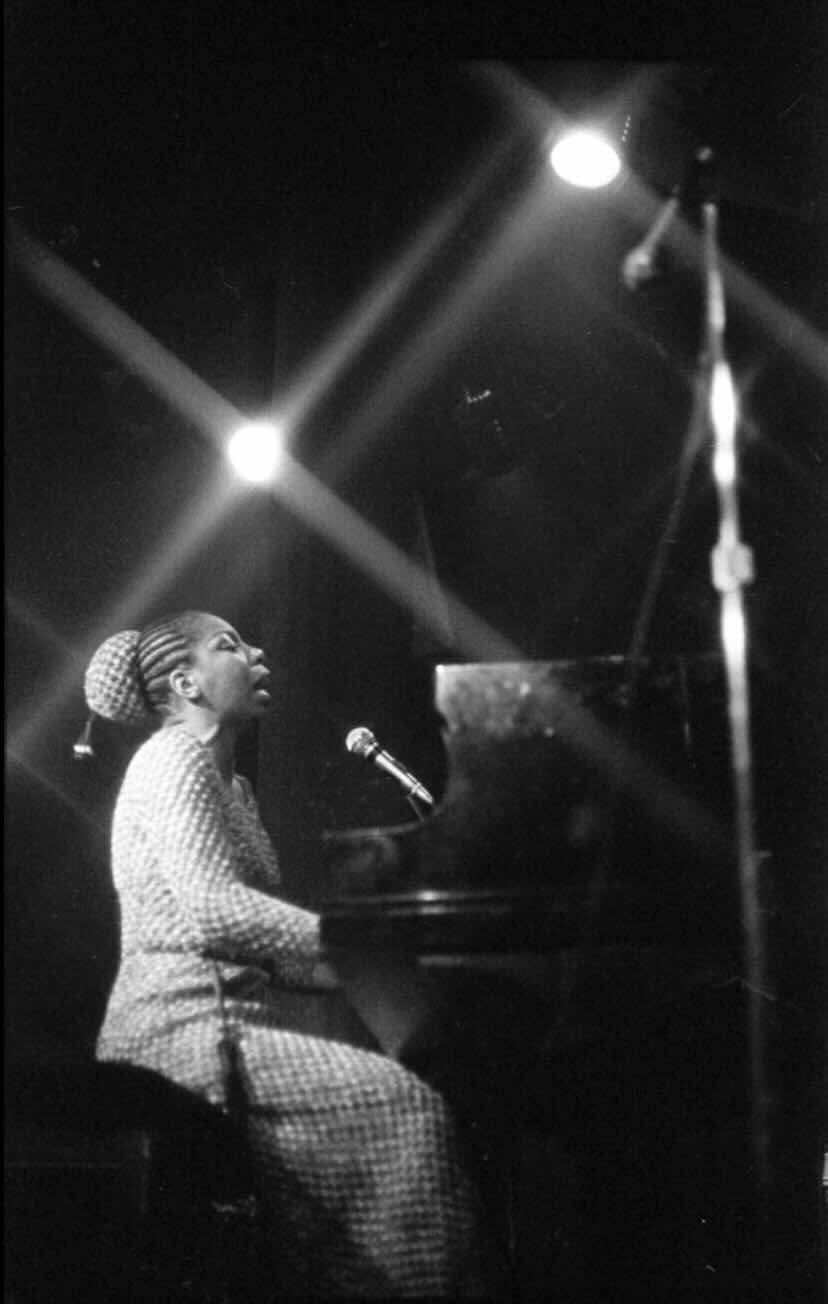

Africans in Britain were “living among those who were growing rich on their suffering”. Winder sifts the piecemeal material on their shadowy lives. Slavery and racism reinforced each other: “through the slave trade, hostility to foreigners achieved a clearer definition”. (One theme that I dared broach: as the fortepiano was becoming an emblem of gentility, the trade in slaves and ivory must have played a role in the colour reversal of its keys—see Black and white).

Through the Victorian era (another German lineage), Britain continued to provide refuge for cliques of intellectual refugees from Italy, Germany, Hungary, and Poland—”not tolerance so much as indifference”. Meanwhile Winder offers some “industrial revelations”. By 1871 Germans were the largest foreign-born minority in Britain, with roughly 50,000 living here by the end of the century, lured by the industrial boom and freedom from state interference.

Chapter 12 is devoted to “Little Italy”—subject of a forthcoming post. From unsanitary lodgings around Clerkenwell, puppeteers, pantomime artistes, and jesters worked the streets. Juvenile organ-grinders led wretched lives, subject to ruthless exploitation by padroni gangmasters, the street urchins bolstering anti-Italian prejudice. In a process of what would be called “chain migration”, service industries emerged: besides instrument makers, delicatessens and restaurants started a revolution in Britain’s eating habits. Italian schools, churches, and barbers were also established. By the early 20th century the “barrel-organ menace” was a remote memory.

Next Winder turns to the influx of the Irish, with around 400,000 arriving in the wake of the 1840s’ potato famine—“penniless, unhealthy, unshod, and unclean, few immigrants have been less welcome”. Though they made a source of cheap labour, resentment at their presence also revived religious sectarianism, and riots were common.

The police, urged on by a sensationalist or malicious public opinion, moved in to confront the hard core, but ended up having pitched battles with the disaffected residents.

Winder sifts through the stereotypes prompting such enmity, noting a significant middle-class component and assimilation. “From unpromising beginnings the Irish developed into a success story”.

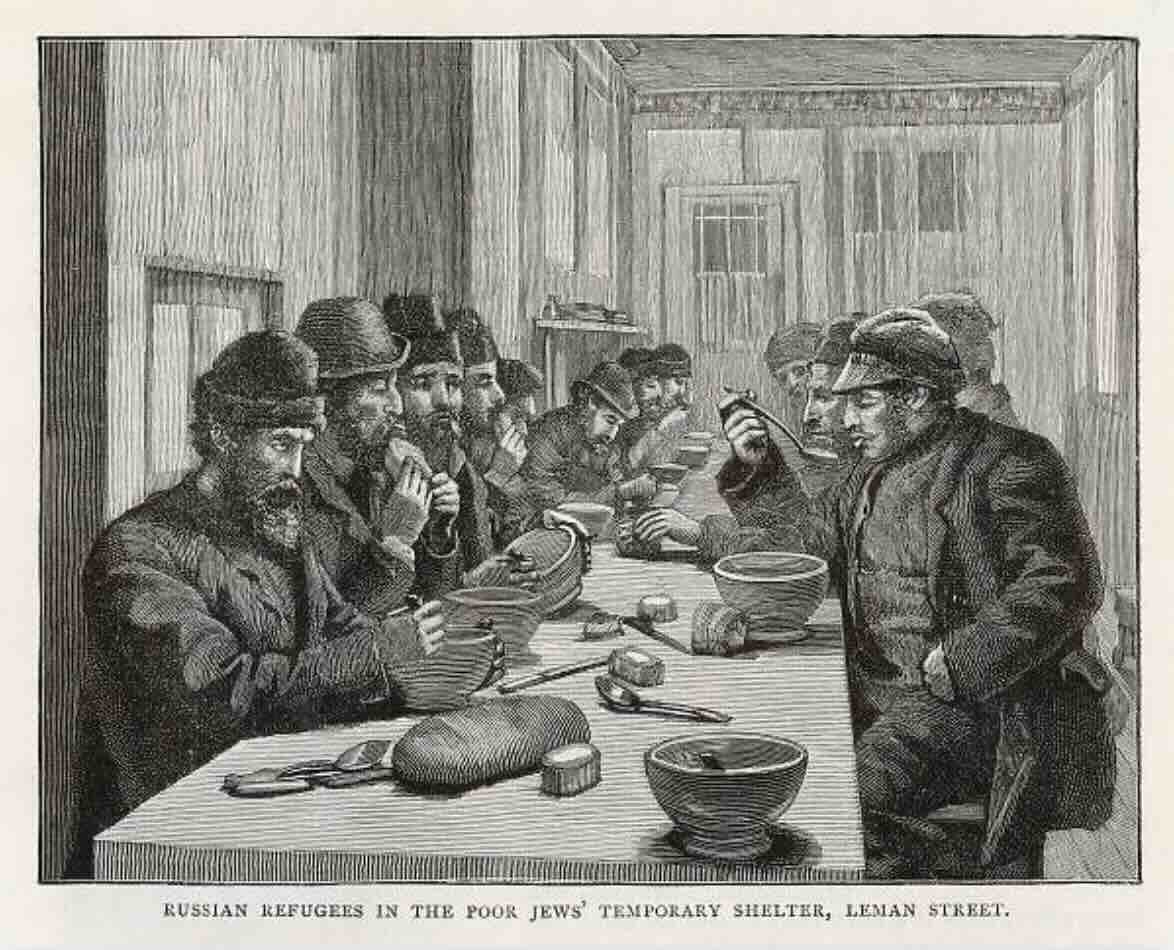

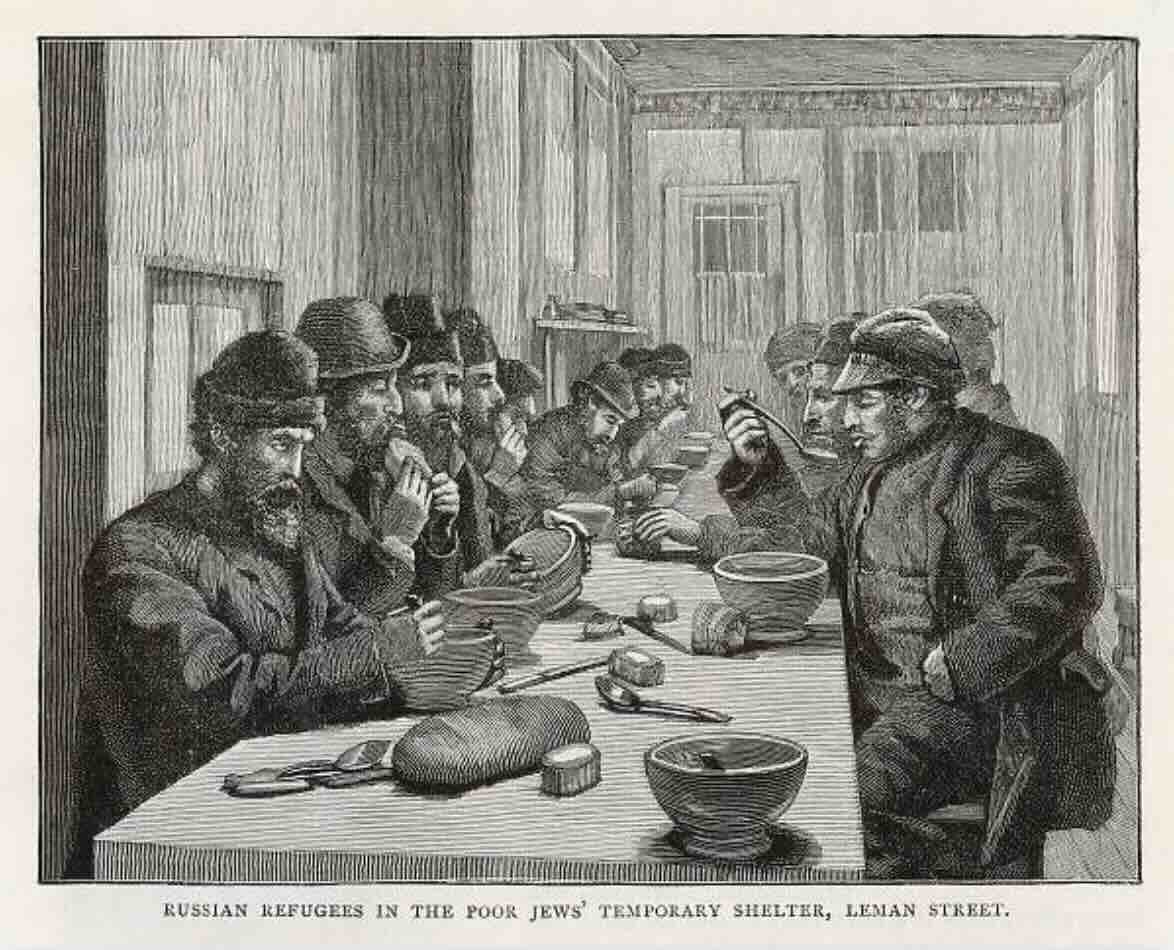

East London, 1890. Source.

East London, 1890. Source.

In 1889 the Shah Jahan mosque was built at Woking, the first in the country, commissioned by the orientalist Dr Leitner, a Hungarian Jew. A new influx came in the 1890s with around 150,000 Jewish evacuees from the pogroms of Tsarist Russia—some prospering while others toiled in murky sweatshops. The anti-immigration lobby grew; fears of being “swamped” had little justification: “between 1871 and 1910, nearly two million Britons emigrated, far more than the number who arrived”. “Lascars”, a broad term for “Asiatic” seamen, established communities in Liverpool, London, and other ports; Chinatowns began to form. Meanwhile “religion, science, and philosophy joined hands to offer a new vocabulary for racial antipathy”.

During World War One anti-German feeling ran high, egged on by the popular press. Like Satnam Sanghera and Fatima Manji, Winder reminds us of the major contribution of Indian soldiers on the battlefield. But

The First World War was the first time that Britain’s working class had travelled overseas in numbers, and when it returned home, it brought with it a sharpened hatred of all things foreign.

Still, foreign food seemed attractive. Curry had already appeared on the menu of a coffee house in the Haymarket in 1773, and in Hidden heritage Fatima Manji notes a short-lived curry-house in 1810—with a delivery service, to boot. Winder goes on:

In 1931 the Bombay Emporium opened near the Tottenham Court Road, providing the first glimmer of what would later become an indispensable part of British life: the Asian shop. In Portobello, you could buy curry powder, poppadoms, and mango chutney.

Several Indian restaurants opened in Soho, as well as in Glasgow and Cambridge—the beginnings of another culinary revolution. By 1970 there were 2,000 Indian restaurants in Britain (cf. Musical joke-dating).

Winder constantly notes both the stars of industry and culture, and the wretched lives of the exploited sweatshop labourers. Between the wars, new arrivals came from Africa and the Caribbean, mostly students. National independence movements grew. In the 1930s a surge of arrivals from the Irish Free State went largely unopposed. Between 1933 and 1939, some 60,000 Jewish refugees managed to reach Britain—including a dazzling array of cultural figures. Still, anti-Semitism, if “only a pale flaring of the venomous feelings in continental Europe”, was substantial. Nicolas Winton’s Kindertransport stood in rebuke to the British government’s exclusionary policies.

Though Britain’s colonial troops again played a major role in World War Two, fear of aliens was again reinforced. Britain recognised its debt to Polish troops, whose naturalisation after the war attracted little controversy. The following waves of immigrants were not so lucky.

* * *

While all this early history is fascinating, it tends to recede from memory as the story enters the period since World War Two. These were desperate times in Britain, as on the continent (see Lowe, Savage continent). Amidst a labour shortage, the substantial new wave of Irish immigrants was accepted, as were Italian workers—the official beginning of our affair with Italian restaurants and fancy coffee machines. But British racism was clear. The term “immigrants” was fast becoming a polite euphemism for “coloured people”. The popularity of black American troops stationed in Britain during the war had been temporary.

The 1948 Nationality Act gave all imperial subjects the right of free entry to Britain. Despite Britain’s postwar poverty, this seemed a tempting opportunity to a fraction of those now entitled to do so. The voyage of the Empire Windrush attracted much publicity (and anxiety), but it didn’t create a surge of similar voyages; only after 1954 did the exodus gather pace, with London Transport initiating a recruitment drive in 1956. The new West Indian arrivals, though few in number, were unpopular. Caricatures represented by Enid Blyton were being ingrained in children—and their parents.

Over the next decade nearly a quarter of a million migrants arrived from the Caribbean, India, Africa, and Hong Kong, making their way “to the country whose authority they were at last shrugging off”. Migrants were unwelcome in all but the poorest neighbourhoods. Jobs were available, but trade unions were largely hostile; housing was a source of exploitation. The migrants soon became disenchanted with their drab, hostile new home. The government seemed to have no plan:

It declined to take any overzealous measures to prevent immigration, while refusing also to stand up for the migrants themselves.

From India came Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims. Cypriots and Hungarians fled conflict in their home countries. By 1958 the Home Office estimated that there were 210,000 people from the Commonwealth living and working in Britain, three-quarters of them male. Racist resentment grew; teddy boys, egged on by Oswald Mosley, caused havoc.

Whereas male workers had formed the core of previous migrants, the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act (“a preference for muddle over clarity, a refusal to be entirely guided by the promptings of either conscience or prejudice”) led indirectly to the consolidation of migrant families and communities. They became more assertive.

Kenyan Asians found refuge from 1967, and then Ugandan Asians from 1970. But emigration also soared through the 1960s. As tourism and package holidays took off, more Italian and Mediterranean migrants arrived. By 1971 there were a million Irish migrants, who no longer prompted resentment—though the anti-German temperament endured, recalled by my orchestral colleague Hildi.

Migrants arrived from India and Pakistan, working in factories and setting up corner shops. As National Front youths indulged in “Paki-bashing” rampages, Brick lane, its population now largely from Bangladesh, again became a centre of racist violence.

The Chinese takeaway was becoming a national institution, largely staffed by migrants from Hong Kong. From 50 Chinese restaurants in 1957, numbers grew to 4,000 in 1970 (at a time when there were around 500 French restaurants!). In Sour sweet Timothy Mo gives a gripping fictional portrayal of the Chinese immigrant experience (cf. Ray Man). Despite the common complaint that newcomers refused to “fit in”,

The group of immigrants who made the least effort of all to fit in were the Chinese, who kept themselves to themselves and socialised almost entirely within their own families. Yet they were the least disliked. They kept their distance, and Britain seemed to like it just fine that way.

The Thatcher era from 1979 exacerbated relations. Still, her government soon had to accept 15,000 Vietnamese boat people, rescuing them from “the twin evils of communism and drowning”. Riots took place in Brixton, Toxteth, and Southall. While noting the violence unleashed between different communities from the Indian subcontinent, Winder observes that no-one liked to admit that “Britain’s urban culture was itself incorrigibly tough and brawling”. The terms “ethnic minorities” and “multiculturalism” came into use; schooling and religious instruction became hotly-debated issues. But

No-one could deny by now that Britain’s railways, hospitals, shops, cafés, and restaurants would have ceased to function without migrant workers.

The collapse of the Soviet bloc regimes, along with ongoing crises around the world, led to new surges. Fundamentalist Islam, the Rushdie affair, and 9/11 posed yet another challenge to Britain’s tolerance of migrants. In 2005 the 7th July suicide bombings in London reinvigorated Islamophobic sentiments in some quarters and made others question the nation’s cosmopolitanism. But somehow a violent backlash was avoided.

Distinctions collapsed between refugees, asylum-seekers, and economic migrants. Measures of successive governments became more draconian while the processing system descended into chaos. The idea that Britain might benefit from migration held little sway. The mass media “seemed eager not just to report discord but to sow it”. The “debate”, if it can be called that, was (and remains) rancid and polarised.

Leaving aside the barmier claims that migrants are all disease-ridden, criminally inclined scoundrels who have no place in our well-mannered, sceptred land, there is a sensible argument that they have been arriving on a scale that stretches our strained welfare resources, provokes social unease (true, though holding the migrants alone responsible is mischievous) and provides, in some cases, cover and opportunity for criminals. The opposing argument states that the demonisation of asylum-seekers is both vindictive and misjudged. It looks at a system that imprisons young children for months, and concludes that we are neglecting our moral duty. It suggests that asylum-seekers bring cultural enrichment as well as entrepreneurial drive: above all, they are individuals striving to live by our own ideals for self-improvement and betterment.

The awkward thing about these two extreme views is that they are both true, or contain truth. Immigrants are not all the same. They represent the full spectrum of human types: dreamers and schemers, rascals and rogues, saints and villains.

For the 2013 edition Winder added the chapter “Choppy waters”, with the Conclusion “Identity Parade”. Though forecasters wildly underestimated the number of those who would take advantage of the 2004 enlargement of the EU to come to Britain, it didn’t submerge the island—and it did provide us with a new generation of trusty Polish workers. Many of the new arrivals didn’t intend to stay.

On nostalgic portraits of English life by Betjeman and Orwell, Winder comments

People who contrive thumbnail sketches of national identity are usually lamenting the passing of their own youth, the fraying of the iconography with which they grew up.

He ponders issues of identity and belonging, observing that statistics are unreliable and open to conflicting interpretations. Aware of the problems of segregation, Winder is not uncritical of multiculturalism. He explores whether integration and diversity are mutually exclusive.

* * *

So I’m not sure quite what we can learn here from the famous Lesson of History. In the Preface to the 2013 edition, Winder explains:

I was not seeking to imply that Britain owes everything to immigration; I was merely drawing attention to a common oversight, which was that the role played by immigrants in the story of Britain has been understated and overlooked. […]

Even if entrenched communities were open to such messages, they might hardly profit from realising that we’ve always been both xenophobic and hospitable, or that migrants assimilate eventually. Still, it’s highly necessary to press the case, and among the vast literature on the topic beyond the rabid pages of the Daily Hatemail, this is a great place to start.

Note also the Migration museum in Lewisham. Cf. Hidden heritage, Vermeer’s hat, and Pomodoro!.

[1] Reflecting the history of migration, a 1743 Huguenot church in Brick Lane became a synagogue in 1898 (after an interlude as a Wesleyan chapel), and then a mosque in 1976 (see also this site).

The Yuepu bian team, 2017.

The Yuepu bian team, 2017. Gongche score, West An’gezhuang village,

Gongche score, West An’gezhuang village,

Funeral procession (detail), Afrasiab (modern Samarkand) murals South wall.

Funeral procession (detail), Afrasiab (modern Samarkand) murals South wall.

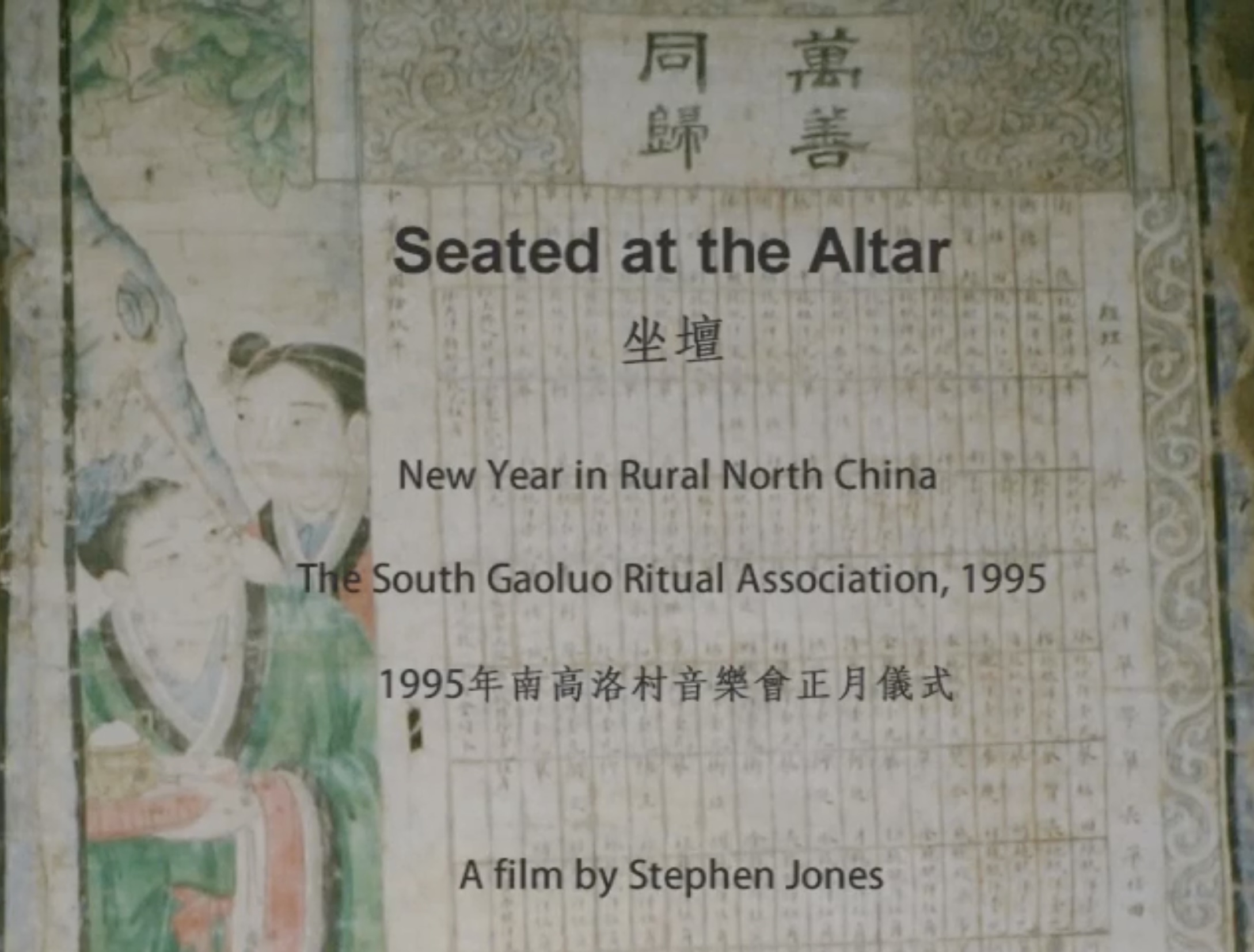

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

Early morning procession to the soul hall, North Xinzhuang 1995. Photo: Du Yaxiong.

Early morning procession to the soul hall, North Xinzhuang 1995. Photo: Du Yaxiong.

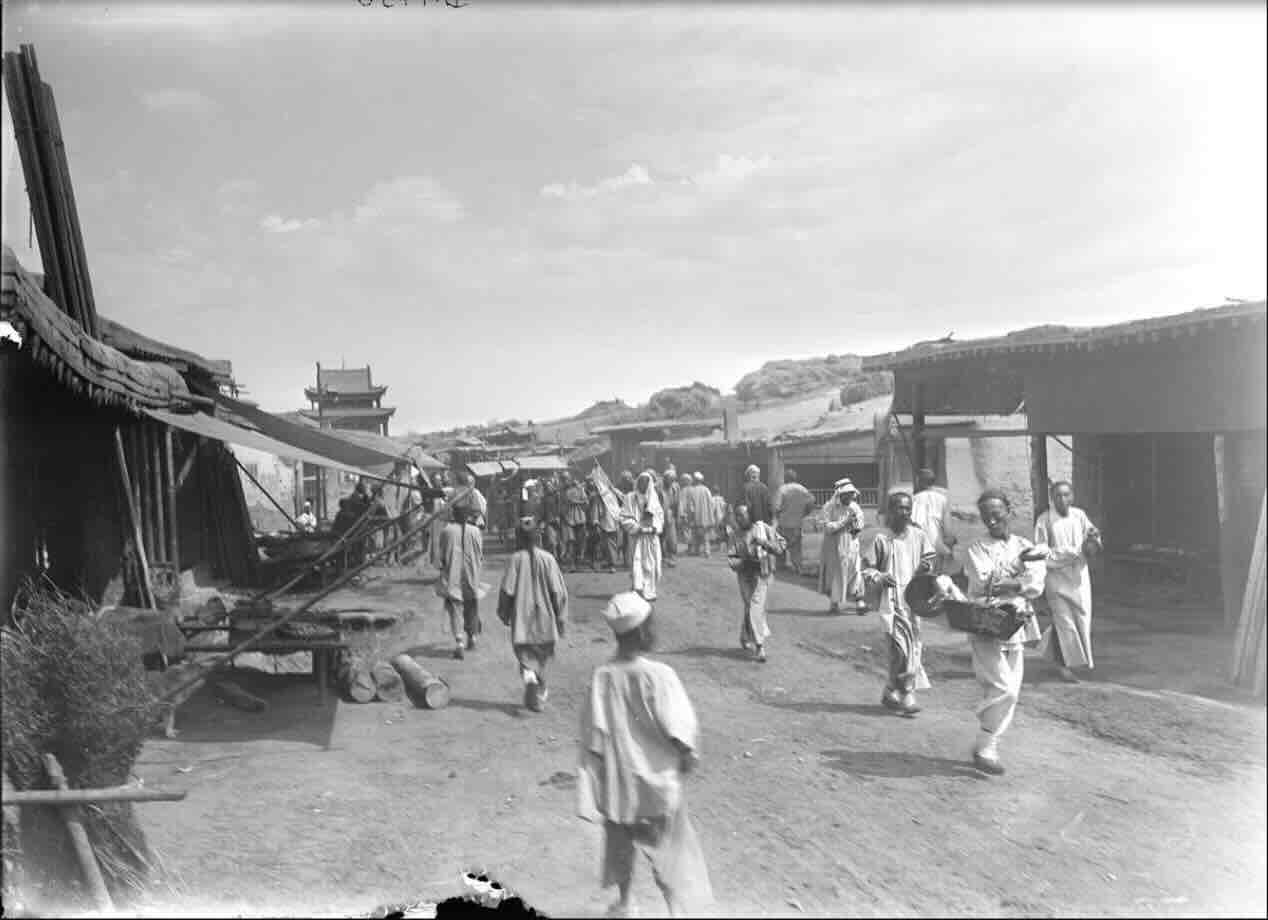

Photo from German Central Asian Expedition, undated (early 20th century):

Photo from German Central Asian Expedition, undated (early 20th century): The Dunhuang region today. Source: Google Maps.

The Dunhuang region today. Source: Google Maps. Konghou, Cave 285, 6th century (detail).

Konghou, Cave 285, 6th century (detail). Henan municipalities.

Henan municipalities.

[3]

[3]

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

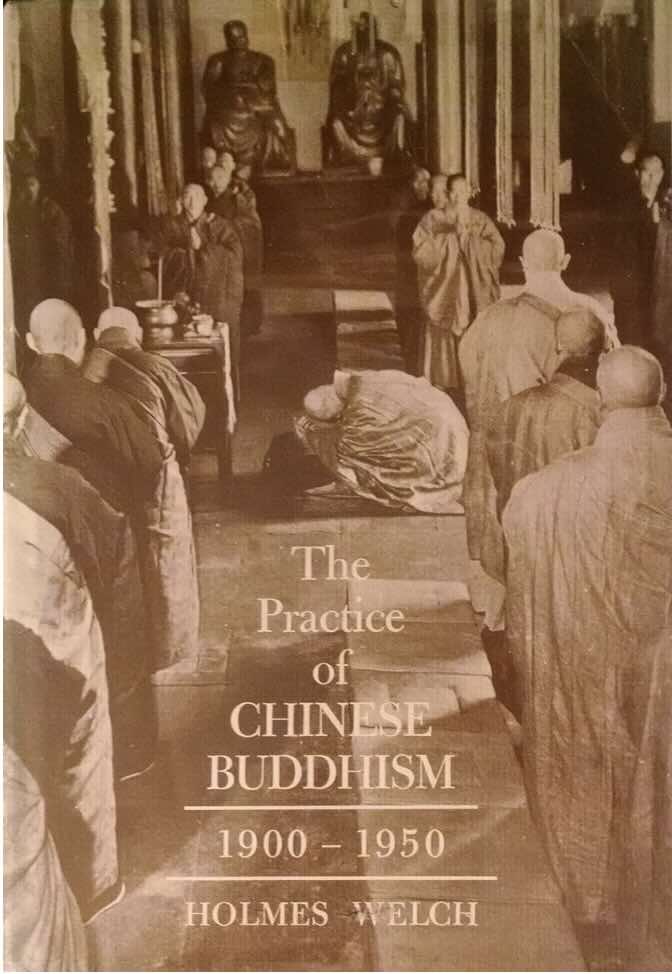

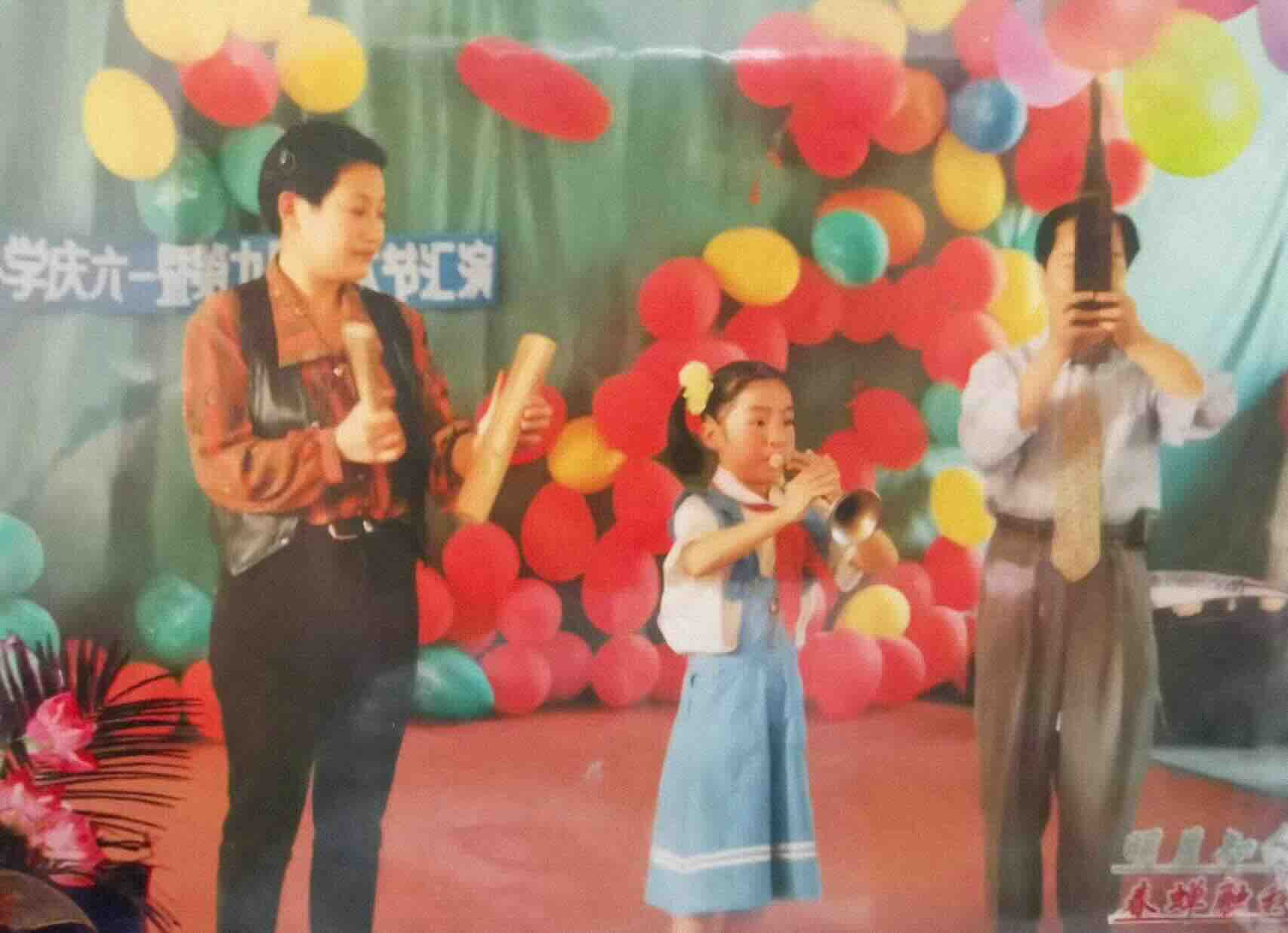

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents.

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents.

I wrote about the symphony

I wrote about the symphony

Stéphane Denève accompanying Laurence Kilsby in Lil Boulanger’s Vieille prière bouddhique.

Stéphane Denève accompanying Laurence Kilsby in Lil Boulanger’s Vieille prière bouddhique.

The Li family Daoists perform the

The Li family Daoists perform the  Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

Image: Paul Childs/Reuters.

Image: Paul Childs/Reuters.  Leaving aside the many other kinds of bowed fiddle (such as kemence and

Leaving aside the many other kinds of bowed fiddle (such as kemence and

String trio with cimbalom at the Meta táncház, Budapest 1993. My photo.

String trio with cimbalom at the Meta táncház, Budapest 1993. My photo.

“Unidentified fiddler” in the southern States. Source:

“Unidentified fiddler” in the southern States. Source:

©BBC/Mark Allan. Source:

©BBC/Mark Allan. Source:

Benjamin Bruns, Christian Immler, Masaaki Suzuki.

Benjamin Bruns, Christian Immler, Masaaki Suzuki.

East London, 1890.

East London, 1890.  Ghost King,

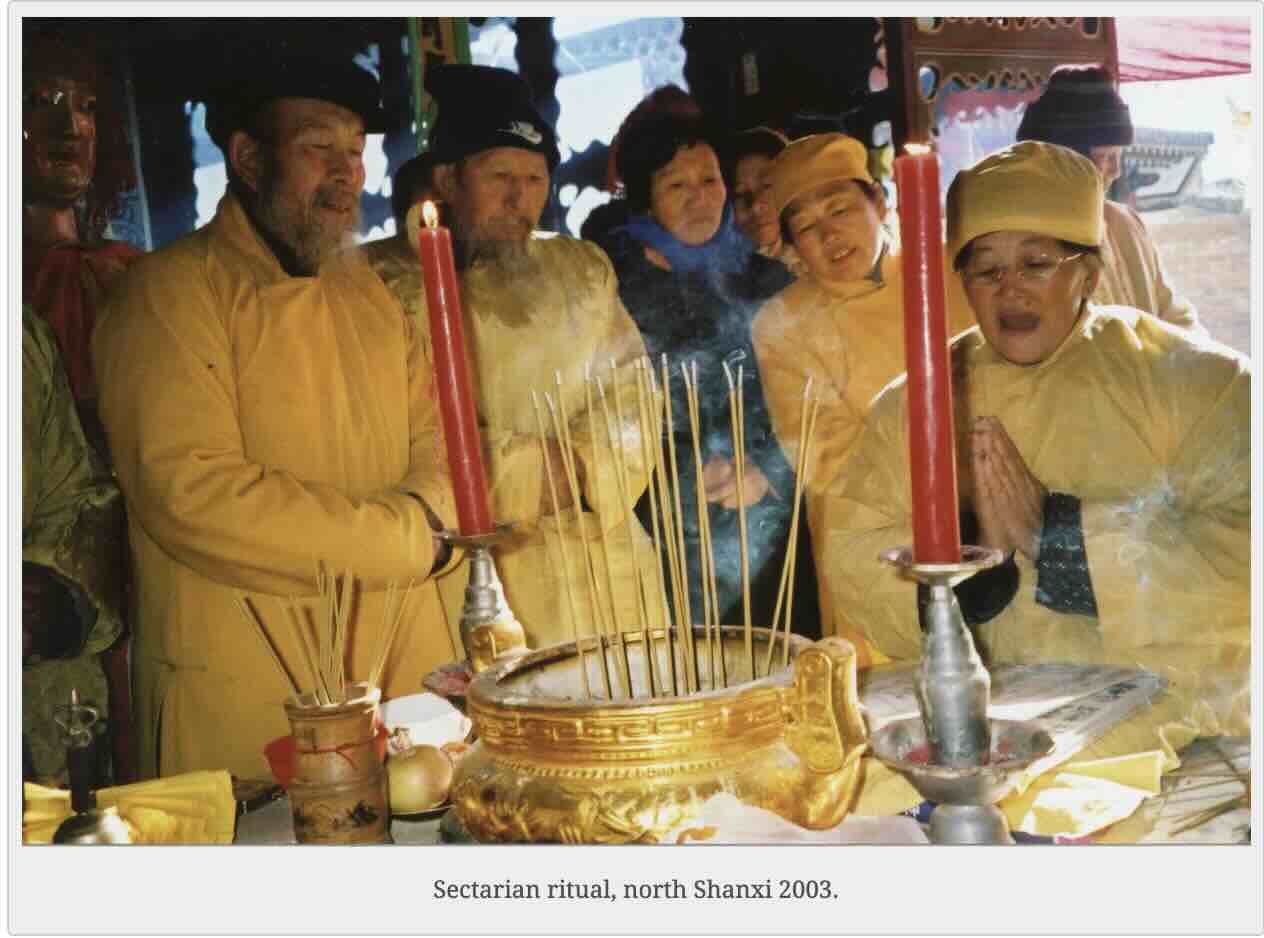

Ghost King,  Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,