Blind people groping at the elephant 瞎子摸象

Following my posts on the tangming bands and the 1956 Suzhou Daoist project, while I have no field experience of Daoist ritual around Suzhou, I’ve been trying to get a basic grasp with the aid of exceptionally abundant secondary sources. So this isn’t so much a review of Suzhou Daoism, as an illustration of the multiple ways of approaching it.

Wu Shirong leading Xiantian bawang zougao ritual, 2011. Photo: Tao Jin.

Research on ritual life throughout the whole of south Jiangsu—Suzhou, Changshu, Wuxi, Shanghai, and so on—ranks close behind that for southeast China and Hunan. Still, ritual activities in these regions are quite different: in the southeast and Hunan, individual household altars (and particularly their ritual manuals) dominate research, whereas in south Jiangsu wider networks of temples and their priests seem more important.

One might suppose that Suzhou Daoism would be a rather easily-defined topic, but it illustrates my comment (Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.3–4) that we are all “blind people groping at the elephant” (xiazi moxiang 瞎子摸象)—only able to describe that tiny part of the total picture that we happen to grasp, never managing to see the whole.

Even for scholars equipped with the skills to study modern or imperial China, Daoist ritual is a daunting topic. And it’s hard to integrate within the changing religious practices and life stories of ordinary people in rural China under successive regimes since the early 20th century. Indeed, this is a general issue in religious studies: the tension between approaching religion as social activity and as doctrine—the manifestation of the Word of God (see e.g. Catherine Bell, Ritual: perspectives and dimensions, and Ritual theory, ritual practice).

For China, we might identify three broad strands of enquiry: social history, ritual (particularly texts), and “music”, that seem to be conducted independently; it seems hard to piece together the multiple pieces of the jigsaw. And whereas change is a major element in studies of social history, ritual and music tend to be treated as eternal; scholars in both the latter fields engage only sporadically with modern society and people’s lives.

Even studies of Daoist ritual and “Daoist music” don’t quite communicate with each other. While sound is invariably a vital element in the performance of ritual, scholars of ritual tend to downplay performance and its soundscape, whereas scholars of “music” may focus too narrowly on it. Both tend to reify, documenting either ritual sequences and liturgical texts or “pieces of music” at the expense of studying social change.

1 Social history: the wider religious context

Here I can only hint at the riches of ritual activity around Suzhou. As throughout China, Daoist ritual is a major theme in ritual activity in the region, but it’s far from the only one. While studies of Daoist ritual tend to favour “salvage” above ethnography, it should be obvious that an understanding of ritual practice depends on the study of local society.

A network of scholars have done impressive research on ritual life around south Jiangsu from the late imperial era, using exceptionally well-documented material on socio-political change since the mid-19th century.

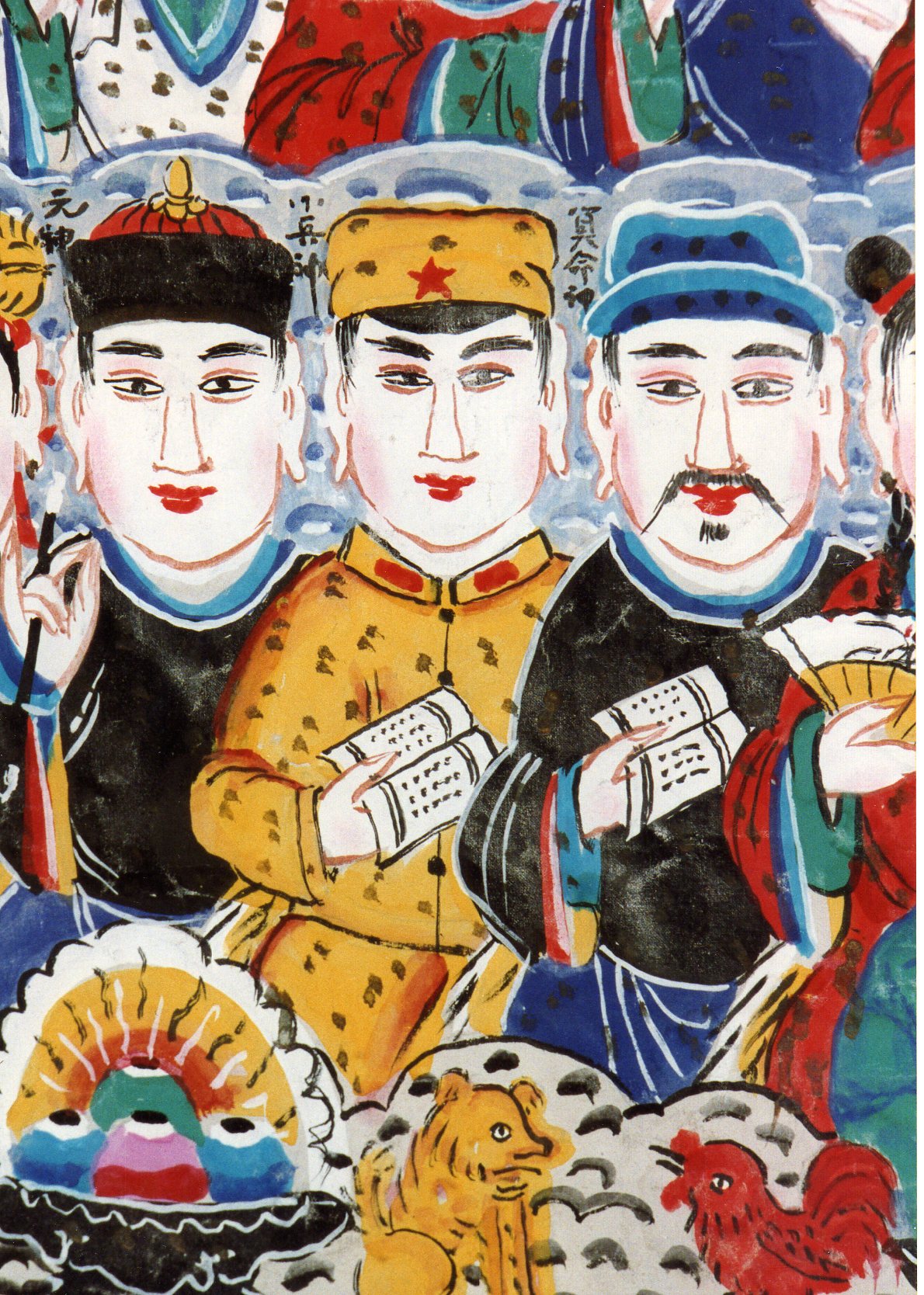

In his book The Taoists of Peking, 1800–1949, Vincent Goossaert makes a convincing case for studying the lives of “ordinary Daoists”. And further, he spreads the net wider to ordinary ritual practitioners. Around Suzhou (as elsewhere), spirit mediums (xianniang 仙娘 or lingmei 靈媒), devotional groups (xianghui 香會, xuanjuan 宣卷, luantan 亂壇, and so on—often sectarian), temple and household Buddhists, and so on are all active, forming an interrelated complex (for further readings on baojuan, see this overview, and n.1 here).

Xuanjuan scriptural group, Jingjiang 2009.

Xuanjuan scriptural group, Jingjiang 2009.

Source: Berezkin and Goossaert, “The three Mao lords”.

A fine introduction to the wider social background is

- Tao Jin 陶金 and Gao Wansang 高万桑 [Vincent Goossaert], “Daojiao yu Suzhou difang shehui” 道教与苏州地方社会 [Daoism and Suzhou local society], in Wei Lebo 魏乐博 [Robert Weller] (ed.), Jiangnan diqude zongjiao yu gonggong shenghuo 江南地区的宗教与公共社会 [Religion and public life in the Jiangnan region] (2015).

They cite a wealth of historical sources from the late Qing and Republican eras, as well as more recent field reports. Like Yang Yinliu, they note nested hierarchies of ritual practitioners, and indeed within the ranks of hereditary Daoists—with a minority of elite fashi ritual masters maintaining their historical contacts with Longhushan [1] and Beijing above the ranks of common household Daoists.

Noting changing ritual practices from the late 19th century, the authors provide rich material contrasting the pre-1949 and modern periods, such as the mentu 門圖 or menjuan 門眷 ritual catchment-area system formerly common throughout the region.

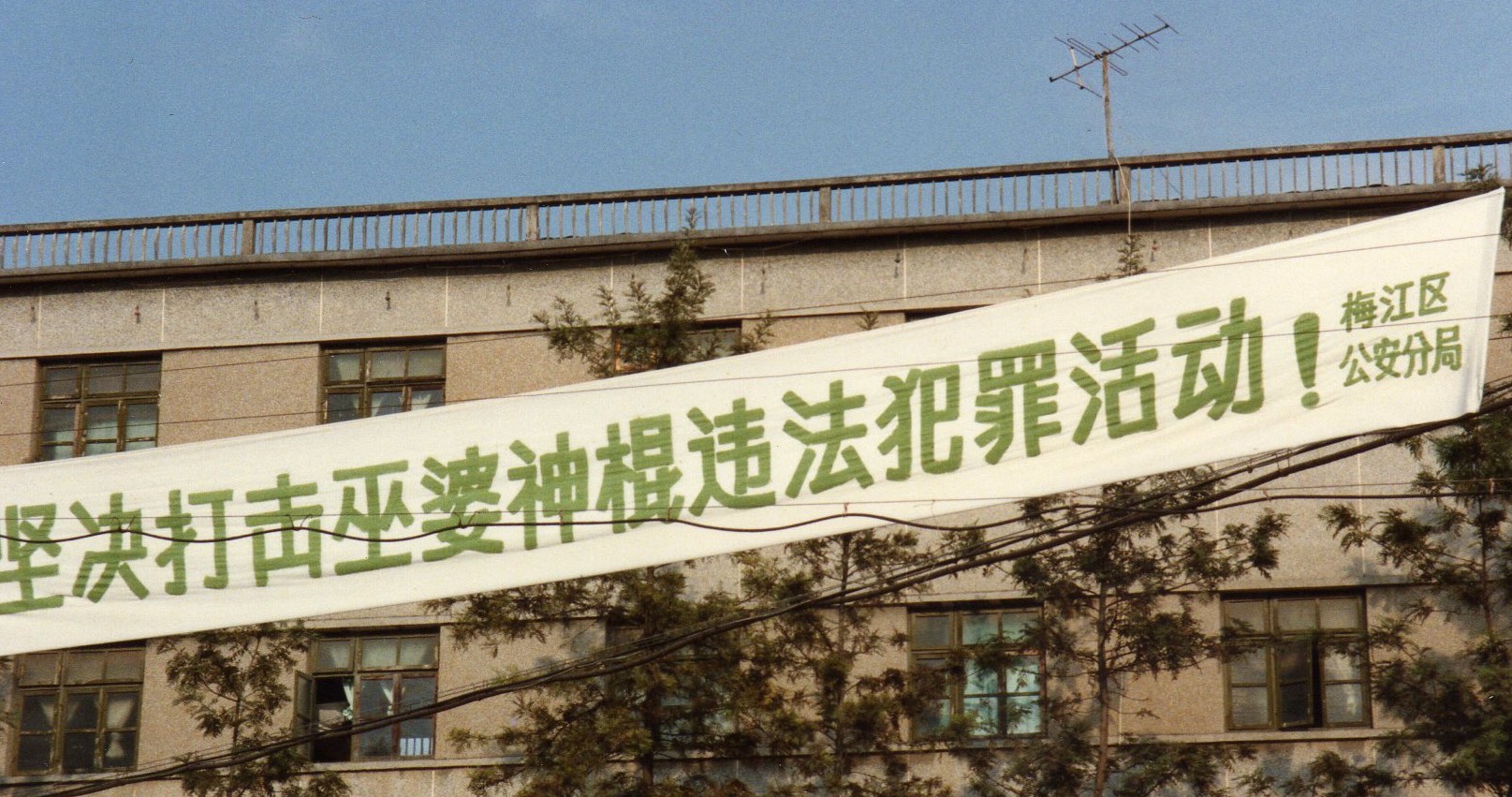

One of the recurring themes in Goossaert’s research is the history of state attempts to manage—and control—unlicensed priests operating at the grassroots level, and the whole diversity of the religious scene.

- “A question of control: licensing local ritual specialists in Jiangnan, 1850-1950”, in Kang Bao 康豹 (Paul Katz) and Liu Shufen 劉淑芬 eds., Xinyang, shijian yu wenhua tiaoshi 信仰, 實踐與文化調適 (Taipei, 2013).

Even in the early 1950s, the Suzhou Daoist association distinguished temple-based Daoists (daofang 道房) and the others (fuying 赴應) whom they hired on a daily basis. The complex relation between Daoists and state supervision has continued to be a major issue in the reform era. Leading Daoist masters who led the preparatory committee for the Suzhou Daoist Association from 1979 included Zhang Xiaoxuan 张筱轩, Ren Junchen 任俊臣, and Zhou Qiutao 周秋涛. Other municipalities also formed Daoist Associations over these years. But there was a wide age-gap between the younger Daoists and their senior masters who had trained under a very different system.

Today, with the increasing vogue of recycling imperial models of governance, we witness to a certain extent a return of this idea that official Daoists and Buddhists holding positions in their respective associations are entrusted with licensing and controlling the vernacular priests in their locales (and indeed, to a certain extent, spirit-mediums who work with them).

By the 2010s, while rituals were still held at the Xuanmiao guan, the temple was partly museified; core focuses serving the ritual needs of communities are now the nearby Chenghuang miao and Qionglongshan (in the western suburbs near Lake Tai).

Another major centre is the Maoshan temple complex. As usual, studies of Maoshan are dominated by ancient history rather than the maintenance of its temple liturgy in modern times; as ever, such prominent temples are subject to great official pressure. Relevant here are

- Yang Shihua 杨世华 and Pan Yide 潘一德 eds., Maoshan daojiao zhi 茅山道教志 [Monograph on Maoishan Daoism] (2007), and

- Ian Johnson, “Two sides of a mountain: the modern transformation of Maoshan”, Journal of Daoist studies 5 (2012).

But there is a multitude of smaller temples throughout the municipalities under the Suzhou region—Kunshan, Wujiang, Changshu, Zhangjiagang, and Taicang.

The revival was gradual. A variety of rituals were soon in demand, such as exorcistic and blessing rituals, rituals for new dwellings, mortuary (including commemorative) rituals, and even wedding rituals. The authors describe four main types of jiao Offering currently performed: taiping jiao 太平醮 for the well-being of a local community; guoguan jiao 過關醮 for life crises, particularly for children; jiao to protect from fire (huojiao 火醮); and rituals for the Thunder God leishen 雷神. They note that 7th-moon rituals to deliver the soul have become rare, but they don’t discuss funerals.

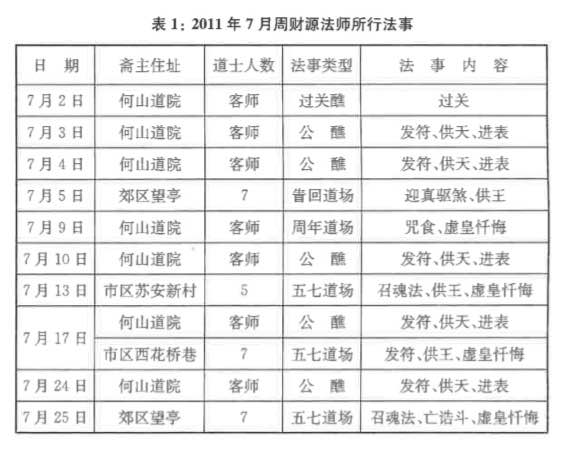

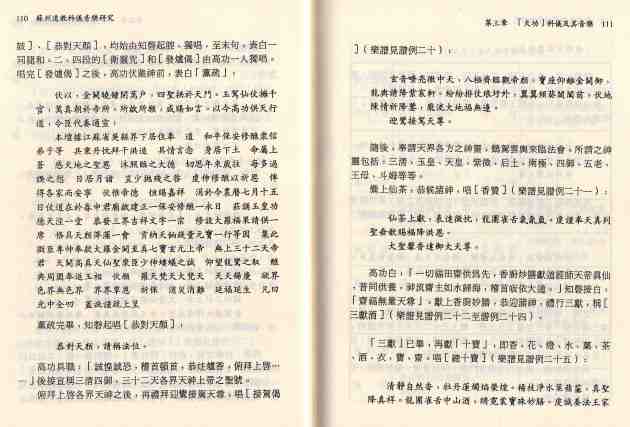

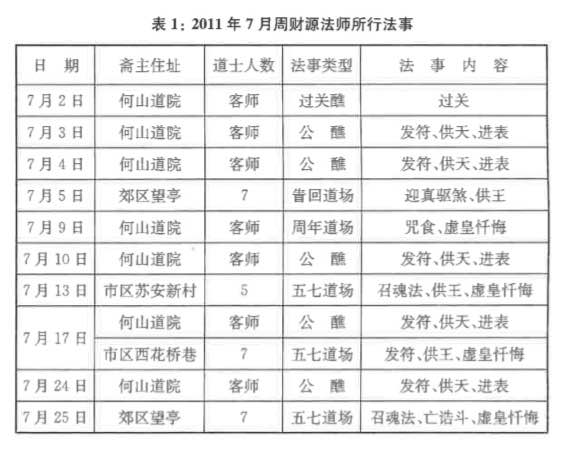

Beyond studies of particular rituals (see below), two tables (pp.105–106) suggest the variety of rituals routinely performed today (cf. the diaries of Li Bin and Li Manshan in Yanggao):

Rituals performed by Tao Jin’s master Zhou Caiyuan in July 2011, showing locations, personnel, ritual type, and ritual segments. For the seven rituals held at the Heshan daoyuan he was a “guest master” (keshi 客师).

Rituals performed by Tao Jin’s master Zhou Caiyuan in July 2011, showing locations, personnel, ritual type, and ritual segments. For the seven rituals held at the Heshan daoyuan he was a “guest master” (keshi 客师).

Rituals held at the Chenghuang miao temple in July 2011, including Communal Offerings (gongjiao), Crossing the Passes (guoguan), commemorative daochang, and so on.

Rituals held at the Chenghuang miao temple in July 2011, including Communal Offerings (gongjiao), Crossing the Passes (guoguan), commemorative daochang, and so on.

As around Shanghai and elsewhere, spirit mediums are crucial organizers. Until the 1950s the xiangtou from the local gentry who invited the elite Daoists to perform rituals, and those attending, were male; nowadays female lingmei (or xianniang 仙娘), and female worshippers, play a leading role. And almost all the rituals (even in the urban temples) are commissioned by rural patrons.

Even some long-discontinued ritual processions resumed—only no longer to the elite temples. For the changing religious scene of festivals, territorial cults, and pilgrimages from the late Qing to the Republican era, see further

- Gao Wansang 高萬桑 (Vincent Goossaert), “Wan Qing ji Minguo shiqi Jiangnan diqude yingshen saihui” 晚清及民國時期江南地區的迎神賽會, in Kang Bao 康豹 (Paul Katz) and 高萬桑 (Vincent Goossaert) eds., Gaibian Zhongguo zongjiaode wushinian: 1898–1948 改變中國宗教的五十年: 1898–1948 (Taipei, 2015)

- Vincent Goossaert , “Territorial cults and the urbanization of the Chinese world: a case study of Suzhou”, in Peter van der Veer ed., Handbook of religion and the Asian city: aspiration and urbanization in the twenty-first century (2015).

In the latter, a nuanced account of the ever-changing fortunes of urban, suburban, and rural temples, the processes of deterritoralization and reterritoralization, he observes:

Judging by current practice, small-scale rituals by local communities typically involve two main kinds of ritual specialists: spirit mediums and scripture-chanting masters. […] Not all territorial communities hire Daoists for their celebrations every year; the scripture-chanting masters provide cheaper, simpler services, complemented by dances and songs formed among the community’s elder women. For the larger celebrations involving Daoists, spirit mediums and scripture-chanting masters are also commonly present; these specialists have a clear division of labour and are not in competition.

See further

And the journal Minsu quyi, always core reading for Chinese ritual studies, continues to publish a wealth of material, most recently here.

2 Documenting ritual practice

While such work is exceptionally rich in social detail, it can’t seek to address the nuts and bolts of ritual practice—which for scholars of Daoism is the heart of the matter.

This is the kind of work for which Tao Jin 陶金 is perhaps uniquely qualified, with his detailed historical knowledge of Daoism and its ritual manuals. One of very few scholars of Daoism who have followed the lead of Saso and Schipper in participant observation, Tao Jin apprenticed himself first to Chang Renchun in Beijing and then, since 2008, to the Daoist masters Zhou Caiyuan 周財源 and Wu Shirong 吾世榮 in Suzhou; in 2018 he was himself ordained.

- Tao Jin 陶金, “Suzhou ‘Xiantian bawang zougao keyi’ chutan” 蘇州《先天奏吿科儀》初探, in Lü Pengzhi 呂鵬志 and Laogewen 勞格文 [John Lagerwey] eds., Difang daojiao yishi shidi diaocha bijiao yanjiu guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji 地方道教儀式實地調查比較研究 (國際學術研討會論文集) (Hong Kong, 2013).

In this article Tao Jin explores the esoteric Xiantian bawang zougao ritual to the Doumu 斗姥 deity. It may be adapted to rituals for both the living and the dead; he documents a mortuary version that he attended at a family home, including randeng 燃燈 and poyu 破獄 segments (see photo above).

Only from the tables can we learn that the group consisted of three liturgists and four instrumentalists; they are not named. Tao Jin’s purpose is not to document normative current practice but to explain aspects of the early evolution of Daoist ritual. He gives only minimal coverage of the soundscape—even basic features like solo chanting, group singing, slow/fast, melisma, the function of percussion and melodic instrumental music.

One may choose to depict a given ritual because it encapsulates the core wisdom of ancient Daoism, or because it is frequently performed today. In my work on the Li family I focus on funerals, because that is their main context, which we can document in detail by observation; I also note their performance of temple rituals and Thanking the Earth, rare or obsolete since the 1950s. Tao Jin comments (in a footnote!) that the Doumu ritual is still performed in the Shanghai region for both the living and the dead, whereas in Suzhou it is now used only for the latter; one wonders about reasons for this difference.

Work of this type is more concerned with tracing medieval antecedents and imperial history than with documenting change within living memory, or indeed performance practice. As with the voluminous material on household Daoist groups in southeast China, documenting the radical social or political changes since the 19th century is left to other scholars.

Another of Tao Jin’s themes is the strong historical link with Daoism in Beijing; [2] and such rituals should also be studied in conjunction with those of Shanghai. While he, with his rich insider’s experience as a participant, should be well qualified to detail the practicalities of ritual life, his main energy is devoted to doctrinal history. Still, if anyone eventually compiles a more comprehensive account of the whole range of rituals still performed, then Tao Jin is the person to do it.

3 Music scholarship

All this seems to put the perspective of musicology in the shade, but this approach does at least provide an impression of current practice.

Clearly, the soundscape of Daoist ritual is crucial; but looking to scholarship on “Daoist music” to understand ritual also has its limitations. Around Suzhou and Wuxi, a reified image of the Shifan instrumental genres works to distract us from both ritual practice and local society; however complex, Shifan is only one supporting element in the performance of Daoist ritual in the region.

In the 1950s “Daoist music” became a palatable way of discussing Daoist ritual; but it obfuscated the issue. Still, whether I like it or not, “Suzhou Daoist music” is A Thing. Like the studies of ritual, such works tend to be heavily laced with generic citations from ancient history. And by contrast with the broader enquiry of social scholars, based on folk practice, they are dominated by the official Xuanmiao guan group. Still, they suggest some clues.

So the riches of Daoist ritual around south Jiangsu (and everywhere) need to be addressed by scholars of Daoist ritual, not just “Daoist music”. I would like to read works without the word “music” in the title, where it is a given that coverage of the soundscape is intrinsic to the task.

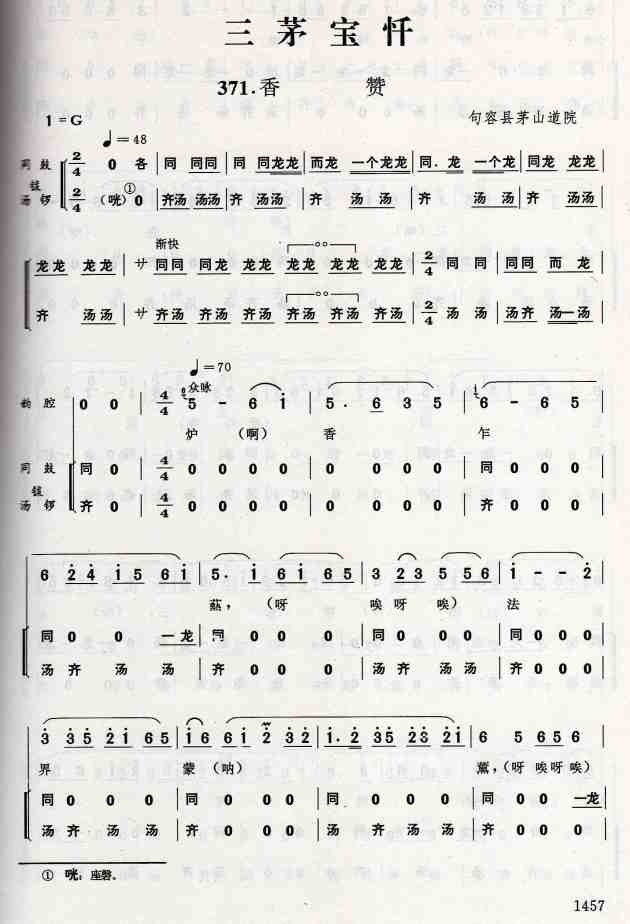

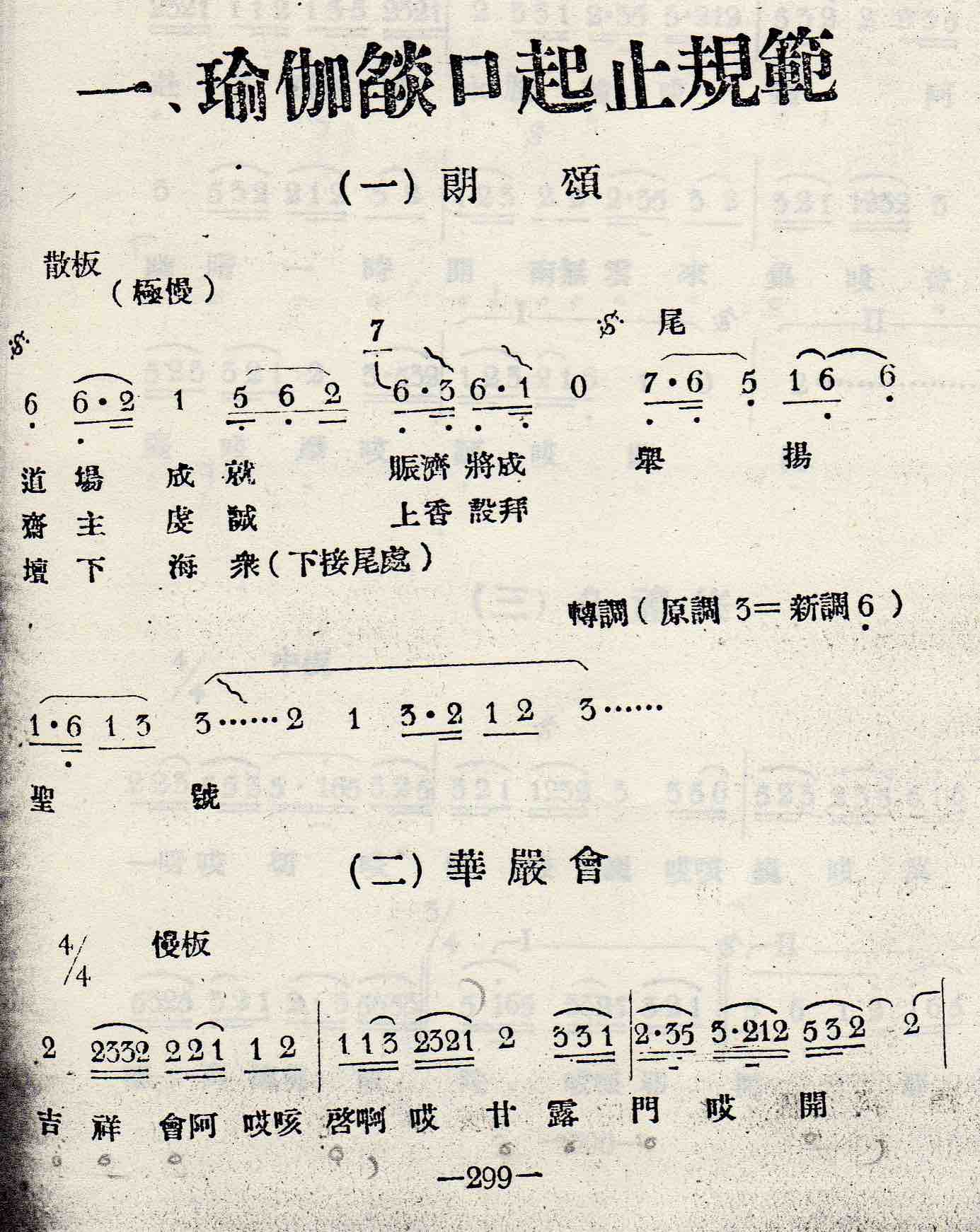

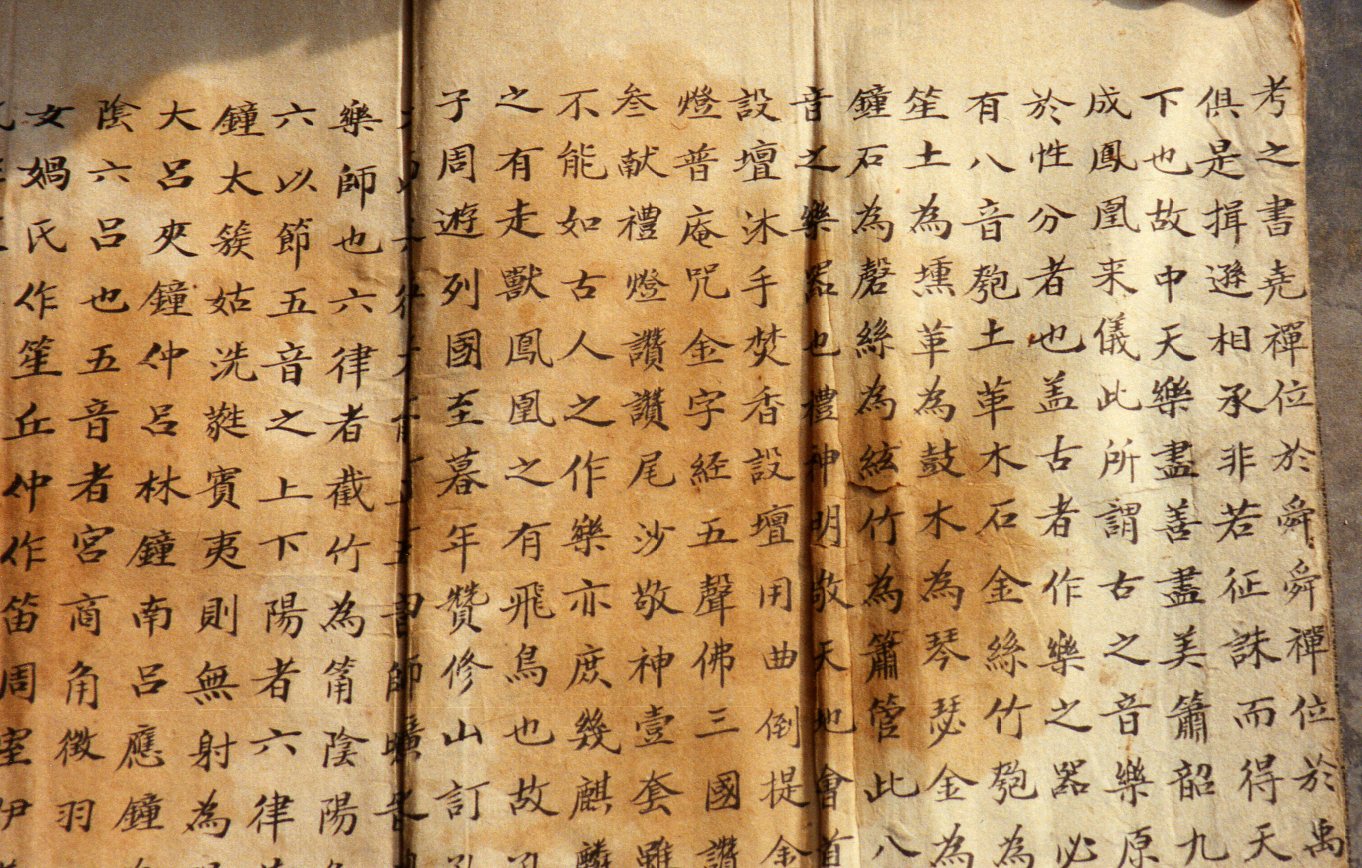

Transcriptions are an important step towards revealing the nuts and bolts of ritual practice, towards suggesting how performers and patrons experience ritual performance. However, scholars of Daoism may be reluctant to take this on board. Learning to read cipher notation requires very little time, but few will take the trouble to do so—perhaps partly because they will struggle to perceive its relevance. Whether for the vocal liturgy or the instrumental music, they might ask: does the manner of performance—notably its sound—matter, as long as the text gets transmitted? (cf. Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.256–7). Indeed, transcriptions—like reproductions of ritual manuals—are merely a form of graphic representation, not easily translated into sound. What we need is film (on which more below).

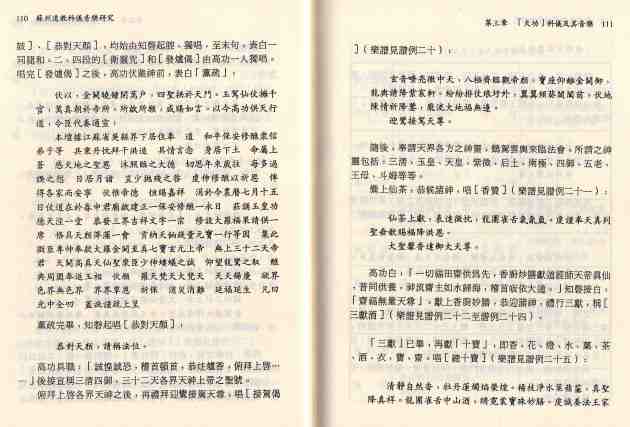

The Anthology

After a very basic introduction, the “religious music” section of the instrumental volumes of the Anthology (Zhongguo minzu minjian qiyuequ jicheng, Jiangsu juan 中国民族民间器乐曲集成, 江苏卷) gives extensive transcriptions of items of vocal liturgy (pp.1439–1645), though it only gives brief notes to contextualize them. The Shifan genres which punctuate them are transcribed separately under instrumental ensembles.

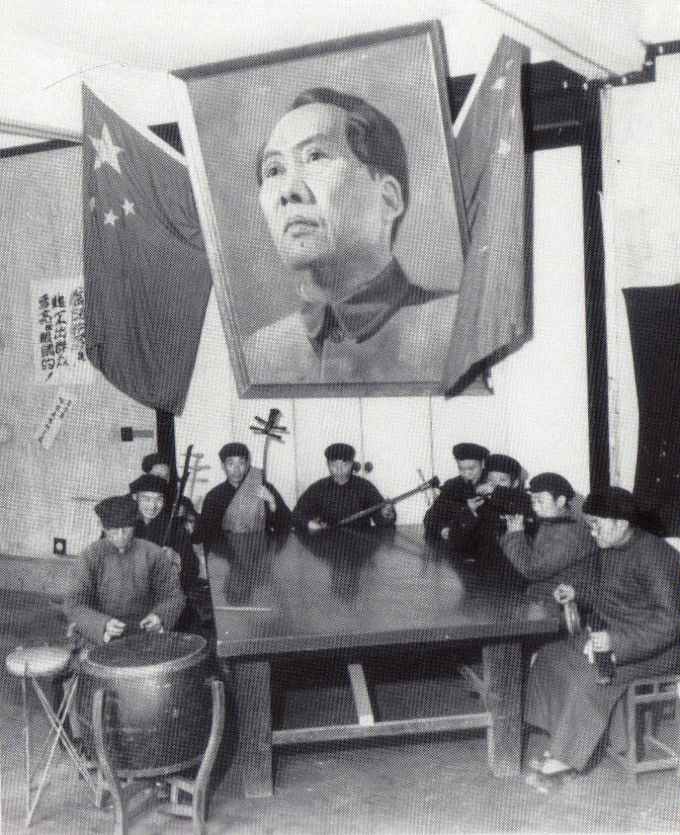

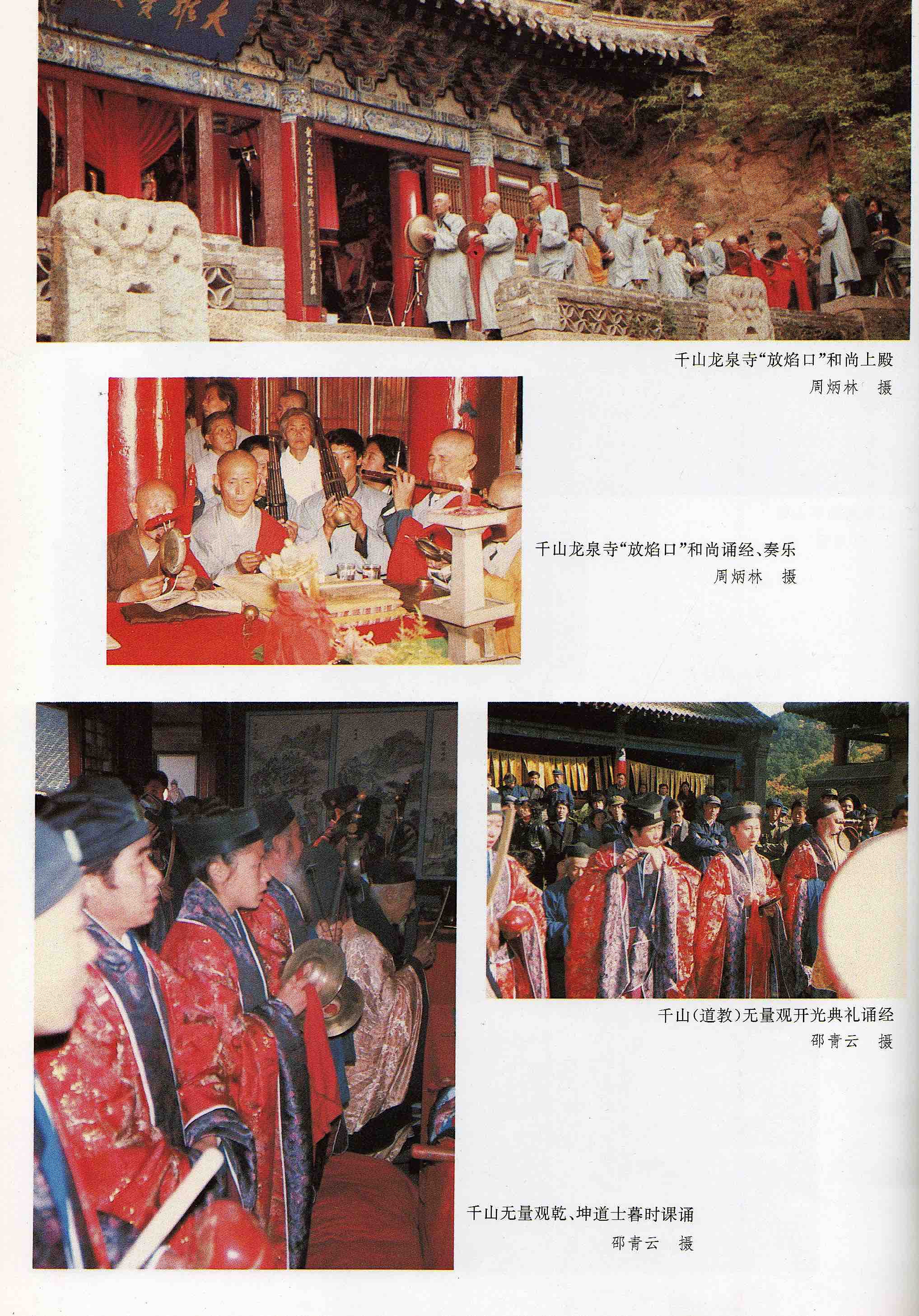

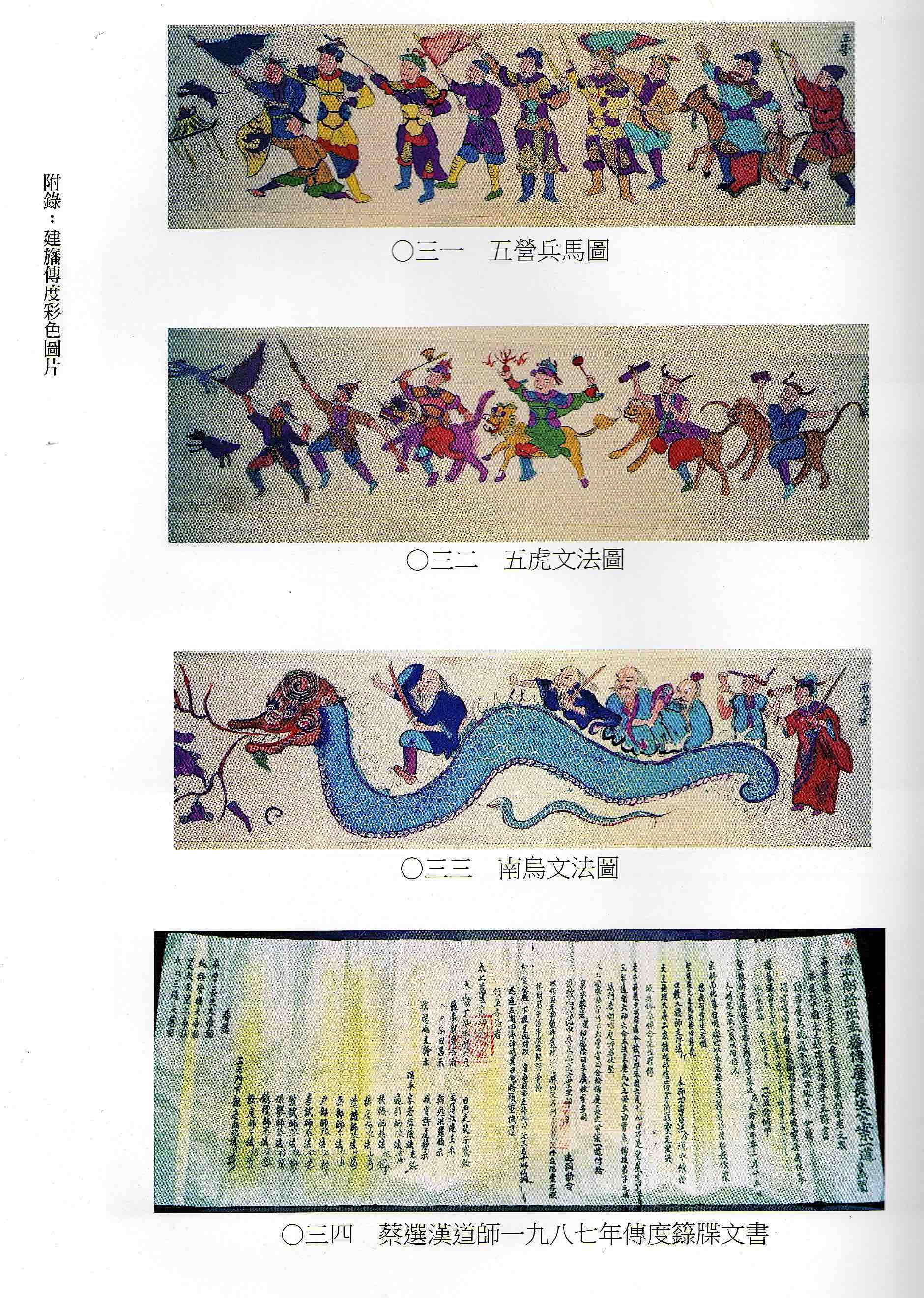

From the Anthology: top (left) Daoist tangming group; (right) Mao Zhongqing leads ritual overture on drum at the Chunshenjun miao temple;

mid: (left) Xue Jianfeng accompanies liturgy on shuangqing lute; (right) Maoshan ritual;

below: (left) chuanhua segment of Quangong/Quanfu ritual; (right) Zhou Zufu accompanies vocal liturgy.

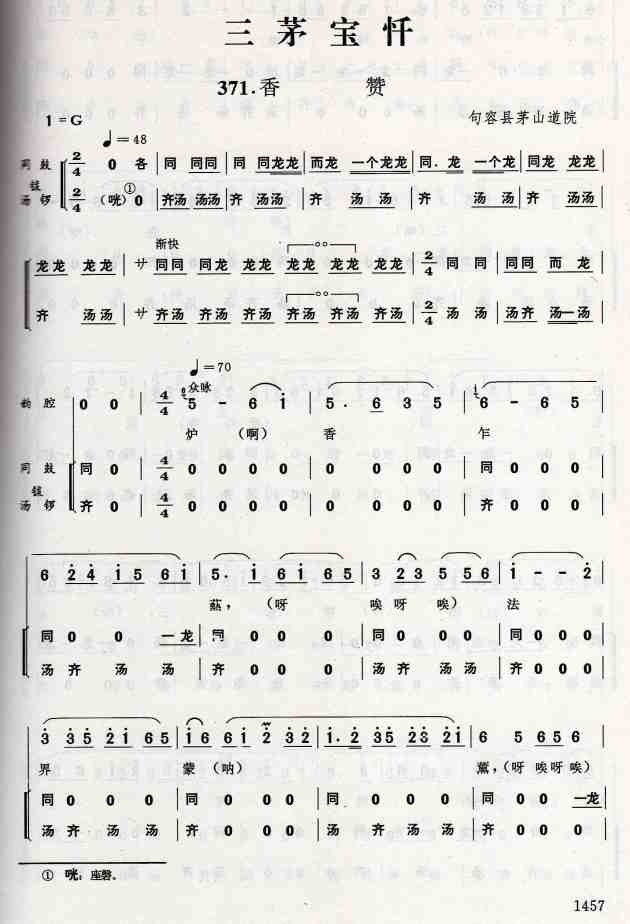

Opening of Hymn to Incense from San Mao baochan, Maoshan,

with percussion prelude and accompaniment.

From Maoshan the Anthology provides transcriptions from the following rituals:

- San Mao biao 三茅表

- San Mao baochan 三茅寶懺

- Yuhuang chan 玉皇懺

- Shangqing risong wanke 上清日誦晚課

And from Suzhou:

- Sanbao chanhui sheshi xuanke 三寶懺悔設[施?]食玄科

- Qingwei gongtian xingdao chaoyuan keyi 清微供天行道朝元科儀

- Quangong/Quanfu 全功全符

- Quangong/Quanbiao 全功全表

- Miscellaneous vocal liturgy

The Anthology continues with transcriptions of Buddhist ritual (pp.1652–1765), mainly of the influential Tianning si temple in Changzhou, as well as Nanjing and Yangzhou, and some items from the xuanjuan scripture groups.

Valuable as the Anthology is, it provides us with clues, starting-points; its material always needs unpacking. Meanwhile, in the substantial series Zhongguo chuantong yishi yinyue yanjiu jihua 中國傳統儀式音樂研究計畫 [Traditional Chinese ritual music research project]

- Cao Benye 曹本冶 and Zhang Fenglin 張鳳麟, Suzhou daoyue gaishu 蘇州道樂概述 (Taipei: Xinwenfeng, 2000)

is a rather slim tome. Their dry list of rituals (pp.39–40), under the basic categories of jiao, fashi, and minor rituals, is less than clear. And instead of clarifying, they go on to discuss the instrumental component. They do then give transcriptions (pp.53–130; texts alone on pp.141–72) of the vocal liturgy from two major rituals (Duiling sanbao chanhui sheshi xuanke 對霛三寶懺悔設食玄科 and Lingbao xianweng jilian xuanke 靈寶仙翁祭煉玄科), but entirely without context.

The Offering to Heaven ritual

In the same series, a much more detailed account of one of the core rituals, as performed by the Xuanmiao guan group, is

- Liu Hong 刘红, Suzhou daojiao keyi yinyue yanjiu: yi “tiangong” keyi weili zhankaide taolun 蘇州道教科儀音樂研究: 以“天功”科儀為例展開的討論 (1999).

It doesn’t consist merely of musical transcriptions, but belongs with the style of the works of Yuan Jingfang 袁静芳 for other traditions (e.g. Beijing, south Hebei, and Baiyunshan), documenting whole rituals in detail.

Liu Hong lists three types of jiao Offering:

- those formerly commissioned by urban dwellers for prosperity;

- Communal Offerings (gongjiao 公醮) commissioned by rural groups assembled by a xiangtou leader (usually a tiangong ritual, as here)

- offerings for individual families.

In a useful section (pp.194–8) discussing flexible elements in the ritual, he notes that whereas before Liberation they used to travel widely in the region to perform lengthy rituals, tailoring them to patrons’ differing demands, since the reforms the patrons come to the Xuanmiao guan temple to have rituals performed, leading to both standardization and abbreviation. This is important, although one now wants similar treatments for all the rituals still performed “among the people”, including those listed in the tables above.

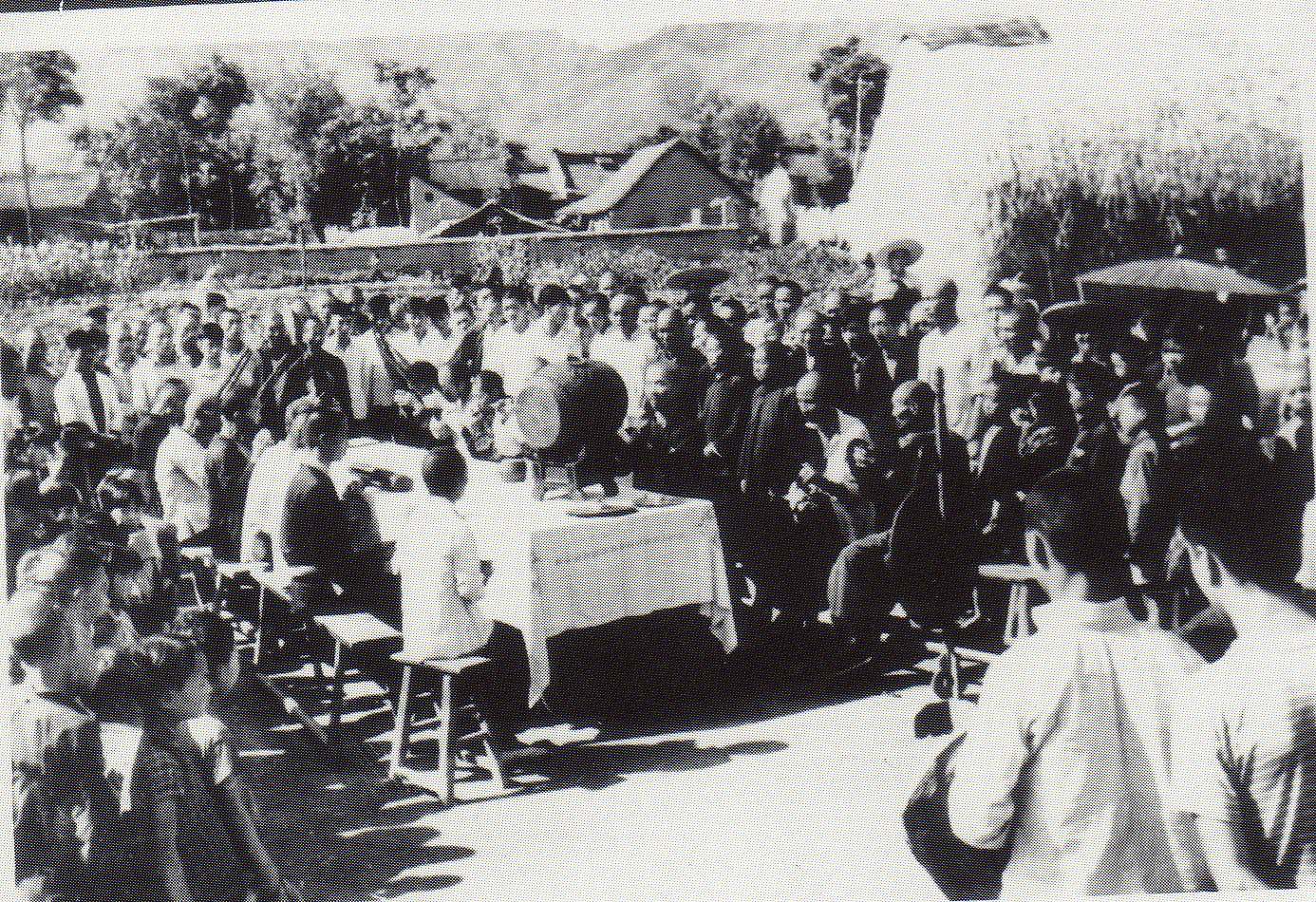

Patrons for tiangong ritual, 1994. Photo: Liu Hong.The tiangong ritual consists of three main sections: Dispatching the Talismans (fafu 發符), Offering to Heaven (gongtian 供天), and Presenting the Memorial (jinbiao 進表)—a sequence also regularly performed by Zhou Caiyuan under the heading of Communal Offering.

From Liu Hong’s description of the gongtian ritual segment.

Liu Hong’s account isn’t limited to melodic items; he includes texts of chanted sections, and describes ritual actions; and like Tao Jin, he provides titles for ritual manuals and diagrams of altars. He also pays rather more attention to social context; for the ritual he attended in July 1994, the “audience” of over one hundred consisted mainly of female peasants from the outlying regions, bringing offerings to be used during the ritual. He lists the performers for a tiangong ritual at the Chunshenjun miao temple in 1995: seven fashi liturgists (led by Xue Guiyuan), two xianghuo helpers and seven instrumentalists (with Mao Liangshan on drum).

Studies of ritual nearby

We might read this material in conjunction with related monographs on Shanghai and Wuxi:

- Cao Benye 曹本冶 and Zhu Jianming 朱建明, Haishang Baiyun guan shishi keyi yinyue yanjiu 海上白雲觀施食科儀音樂研究 (1997) documents a 1994 performance of the shishi ritual, and contains reproductions of four ritual manuals.

- Qian Tiemin 錢鐵民 and Ma Zhen’ai 馬珍媛, Wuxi daojiao keyi yinyue yanjiu 無錫道教科儀音樂研究 (2 vols., 1999) contains transcriptions of the vocal liturgy (pp.165–568), but is dominated by the instrumental repertoire.

For other volumes on Shanghai in the important Minsu quyi congshu series, see n.3 here, including a review by Poul Andersen.

So such studies by musicologists contain considerable material for the scholar of Daoism.

4 Maoism

Though the Maoist era was a crucial period for transmission, details remain elusive. Tao Jin and Goossaert give a bare outline (p.99–100). Household Daoist Zhou Caiyuan recalled a large-scale zhutian hui 朱天會 ritual in the late 1950s at the Wulu Caishen miao temple near the Xuanmiao guan in Suzhou. Maoshan temples managed to maintain activity too: in 1963, roughly 20,000 believers attended a kaiguang 開光 inauguration ritual at the Jiuxiao gong temple there. [3] Even the performance of such rituals under Maoism suggests a nuanced picture, but few details emerge of more routine practice—including funerals, always an important context.

A 1956 list of temples in the city of Suzhou (Suzhou daojiao keyi yinyue yanjiu, pp.15–18) gives a stark picture of the decimation of the physical religious landscape there. Suburban and rural temples may have been hit less hard, though ritual activity there too would have been severely limited.

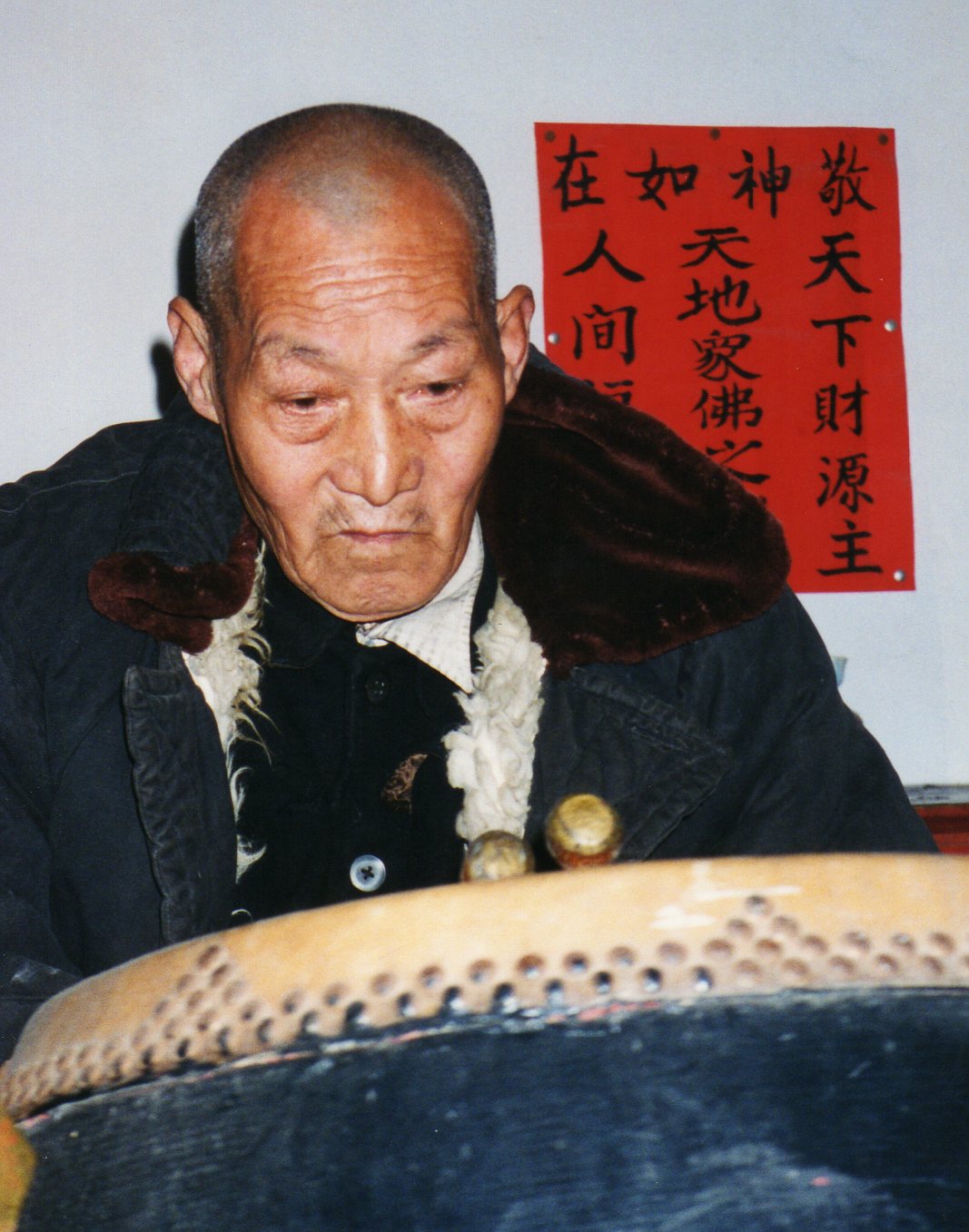

5 Lives

To return to Goossaert’s plea, it’s worth exploring the lives of the ritual performers.

For scholars of Daoism, the fashi ritual specialists properly take priority over the “musical” Daoists. But the 1957 volume Suzhou daojiao yishuji only lists their names, and the Anthology biographies concern not those specializing in liturgical practice but performers noted for their instrumental accomplishments who went on to achieve fame under Maoism as members of secular state troupes. Still, these Daoists are not mere “musicians”: they have long experience performing lengthy rituals. While some of them formally served as temple clerics before Liberation, most were household Daoists. [4]

Some of the most famed performers are renowned for their drumming (a major component of Daoist ritual around the region), such as Mao Zhongqing and Zhou Zufu, as well as Zhu Qinfu in Wuxi. Scholars pay attention to the complex drum sections that punctuate the instrumental suites, rather than the less virtuosic art of accompanying vocal liturgy (on which, for Yanggao, see here.)

Most of these biographies describe prominent Daosts recruited to the Xuanmiao guan temple group in Suzhou:

Mao Zhongqing 毛仲青 (1915–?)

Mao Zhongqing studied from young with his father Mao Buyun 毛步雲, a priest in the Huoshen dian shrine attached to the Xuanmiao guan. He studied dizi flute with Cao Guanding 曹冠鼎 of the Jifang dian shrine, sanxian plucked lute with Hua Yongmei 華詠梅 of the Wenchang dian shrine, and the whole Shifan repertoire with Dai Xiaoxia 戴啸霞, a Daoist attached to the Greater Guandi miao temple. From the age of 12 sui he was working for the Caishen dian temple.

After Liberation he was recruited to a Music Research Group in the Suzhou Daoist community for the “Resist America, Support Korea” Association. In 1953, like Cai Huiquan, he was employed in the Central Chinese Broadcasting Orchestra, along with his fellow Daoists Wu Mingxing 吳明馨, Qian Zhanzhi 錢綻之, and Hua Lisheng 華麗生. But already in late 1954 he requested leave to return to Suzhou, where he worked for the Suzhou Daoist Study Committee.

In 1956 he took part on drum and tiqin fiddle in the major project to document a complete jiao Offering ritual. Wu Xiaobang, leader of the project, went on to organize the Heavenly Horses Dance Experimental Office (Tianma wudao shiyanshi 天马舞蹈实验室) in Shanghai, with whom Mao Zhongqing toured widely from 1958 to 1960. When the group folded in 1961 he once again returned to Jiangsu, joining the provincial Kunqu troupe. In the early years of the Cultural Revolution he was kept on at the reception office there, but he took early retirement in 1970, returning to Suzhou. In 1979, as tradition restored, he was part of an illustrious group of thirteen Daoists gathered together by cultural officials to record. He was now assigned to the Suzhou Song-and-Dance Ensemble, also taking part in the Suzhou Kunqu Troupe.

Zhou Zufu 周祖馥 (1915–97)

From a background of Kunqu, Zhou Zufu was adopted after his mother’s death into the hereditary ritual tradition of the Zhou family in Huajing village of Wuxian county, descended from the Renshi tang 仁世堂 hall, performing along with four brothers. Aged 17 sui he studied Daoist percussion with Xu Yinmei 許吟梅 of the Caishen dian temple of the Xuanmiao guan, and from 21 sui he invited Zhao Ziqin 趙子琴, an eminent Daoist attached to the Zongguan tang 總管堂 hall, to Huajing to teach them sanxian. After the Japanese occupation, with travel disrupted, he studied Shifan with Zhu Peiji 朱培基 (aka Zhu Boji 朱柏基). By now he was a respected performer in Daoist ritual and tangming groups around the countryside. He was given a post in the Suzhou Daoist association, expanding his ritual activities to the city. After the Japanese were defeated he was the only rural Daoist to take part in the Yixuan yanlu 亦玄研庐, one of many such official Daoist groups formed since the 1920s.

Zhou Zufu, ritual transmission. Source: Liu Hong, Suzhou daojiao keyi yinyue yanjiu.

After Liberation Zhou Zufu was recruited to the Suzhou Daoist Music Research Group. In 1953 he was assigned to the Minfeng Suzhou Opera Troupe (forerunner of the Suzhou Kunqu Troupe), and in 1957 he went on to the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra. Again, he had to return to the Suzhou countryside with the 1962 state cuts.

Following a typical lacuna in the account, he was recalled to the Suzhou Kunqu Troupe in 1977. In 1984 he was recruited to the Xuanmiao guan temple. That year he performed in Venice with a combined group from Suzhou (also including qin master Wu Zhaoji), arranged impressively by Raffaella Gallio, first foreign student at the Shanghai conservatoire from 1980—who incidentally was instrumental in helping me realize that Chinese folk music was reviving (see here).

The account lists official festivals at which he took part through the 1980s and 1990s, including the 1990 Beijing Festival of Religious Music. But by the late 1980s he was also a leading light in rituals at the Xuanmiao guan, teaching the new generation.

Jin Zhongying 金中英 (1925–96)

A hereditary household Daoist from Suzhou city, Jin Zhongying studied at sishu private school from the age of 6 sui, but had to withdraw after two years since the family could no longer afford the fees. When he was 12 sui his father died, and he gradually began performing in rituals, learning instruments and liturgy from masters like Zhao Houfu 趙厚福 (see below), and learning further from 15 sui in the Shouxuan xiejilu 守玄褉集庐 Daoist academy. In 1945, as the Japanese were defeated he took part in its successor the Yixuan yanlu, but their activities were soon curtailed by the civil war. In 1948 he studied with Xu Yinzhu 許吟竹 at the Wenchang dian temple.

After Liberation, in 1951 he too was enlisted to the Suzhou Daoists’ propaganda activities for the Korean War, and from 1953 he headed the second Daoist Music Research Group, with a brief interlude in the Minfeng Suzhou Opera Troupe. He had an impressive collection of ritual manuals, and it was he who in 1953 provided the early Juntian miaoyue score by Cao Xisheng. He was one of the organizers of the 1956 project, and the main author of the resulting volume; and like Mao Zhongqing he went on to join the Tianma Troupe in Shanghai. In 1960 he was recalled to oversee the Suzhou Chinese Music Troupe. From 1965 he held successive cultural posts in Suzhou. He was a leading light in the revival from 1979.

As I observed in my post on the tangming bands, few Daoists would have been reluctant to take up such employment. They had to work out how to survive under the new regime; such posts offered them a reliable “food-bowl” and protected them, mostly, from accusations of “feudal superstition”.

By contrast with other regions, there was more official research activity in Suzhou under Maoism, based to a degree on the lively Daoist institutions of the Republican era. But such biographical sketches are frustrating. They were all versatile instrumentalists, but for details on their ritual and liturgical practice we have to seek elsewhere.

Cao and Zhang give further brief biographies (pp.131–40)—still based more on “musicians” than on liturgists. In addition to the Daoists above, they list:

Zhao Houfu 趙厚福 (1908–?)

Son of the great Daoist Zhao Ziqin 趙子琴, who had over two hundred disciples, Zhao Houfu also studied percussion in the 1930s with the Daoist master Dai Youxia 戴攸霞. From 1951 he was a member of the Suzhou Daoist Music Study Group, and he took part in the 1956 project, going on to the Tianma Troupe.

Xie Jianmei 謝劍梅 (1912–88)

From Suzhou city, from the age of 16 sui he learned with Li Peiyuan 李培元 and Shao Shilin 邵世琳, with further training in liturgy from Qian Zhanzhi 錢綻之, Wu Dinglan 吳鼎蘭, and Jin Shenzhi 金慎之. He became a priest at the Caishen dian shrine of the Xuanmiao guan after the 1945 victory over Japan. In 1951 he joined the Suzhou Daoist Music Research Group, working alongside Jin Zhongying and Hua Lisheng. Later he was recruited to the Kunshan Dasheng Yueju Opera Troupe. During the Cultural Revolution he worked at a primary school. From 1981 he was employed at the Xuanmiao guan.

Cao Yuanxi 曹元希(1913–89)

A hereditary Daoist at the Huoshen miao temple in Suzhou, he was a descendant of Cao Xisheng, compiler of the Juntian miaoyue score. After studying with Shao Shilin 邵士琳 and Xu Yinmei 許吟梅, he became abbot of the Huoshen miao. In 1951 he too joined the Suzhou Daoist Music Research Group, and he took part in the 1956 project. From 1957 he was in the Heavenly Horses dance troupe, moving on to the Suzhou Chinese Music Orchestra and the Suzhou Kunqu Troupe, where he worked until retiring.

Hua Lisheng 華麗笙 (1915–89)

Hua Lisheng became a priest in the Jifang dian 機房殿 shrine of the Xuanmiao guan at the age of only 10 sui, learning ritual with Cao Guanding 曹冠鼎. In 1946, with Zhang Jingyun 張景雲, Li Youmei 李友梅, and Zhang Yunmou 張雲謀 he formed the Yunji she 雲笈社, a short-lived organization for Daoist research. In 1952 he was recruited to the Central Broadcasting Troupe, but returned home due to ill health. Through the Cultural Revolution he made a living from making paper boxes in Xuanmiao guan Alley. From 1981 he worked for the preparatory group for the Suzhou Daoist Association, becoming secretary when it was established in 1986.

Mao Liangshan 毛良善 (b.1927)

From Weiting in Wuxian county, Mao Liangshan was adopted at the age of 6 sui by Zhao Houfu, learning Daoist ritual with him and Zhao’s father Zhao Ziqin. He became a priest at the Xiuzhen guan temple in Suzhou at the age of 13 sui, under the tutelage of Shen Yisheng 深宜生. On the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution he returned to Weiting to work in the communal fields. In 1984 the Suzhou Daoist Association summoned him to perform rituals.

Xue Jianfeng 薛劍峰 (b.1925)

A hereditary Daoist, Xue Jianfeng became a temple priest at 14 sui, studying with his father Xue Songqing 薛松卿 and Shao Shilin. From 18 sui he was abbot of the Liushuixian miao 柳水仙廟 temple. After the disruption of the Cultural Revolution, he returned to the Xuanmiao guan in the early 1980s. While a versatile instrumentalist, he specialized in the shuangqing 雙清 plucked lute. Along with Zhou Zufu and Mao Liangshan he trained the new generation.

Jiang Jierong 蔣介榮 (b.1926)

From Wuxian county, Jiang Jierong began studying Daoist ritual from the age of 8 sui with his father Jiang Nianxuan 蔣念萱. His father died when he was 13 sui, whereupon he studied “shendao” 神道 (the tangming ritual style) for three years under Tao Qinghe 陶慶和 (Tao Dawei 陶大微). At the age of 16 sui he became a priest at the Qingzhou guan temple in Suzhou, furthering his studies with Xu Yinmei. Upon land reform he left the clergy, but continued working as a household Daoist. After a long lacuna in the account, he resumed ritual life upon the reforms, and was recruited to the Suzhou Daoist Association in 1990.

Here I may as well include a renowned Daoist drummer from nearby Wuxi, on whose reputation the wider awareness of the art of Daoist drumming in south Jiangsu is largely based—it’s worth recalling that Chinese musicologists were studying ritual in mainland China long before other scholars, and that this began with the great Yang Yinliu‘s immersion in Wuxi Daoism.

Zhu Qinfu 朱勤甫 (1902–81) [5]

Born to a poor family in Zhucuntou village of Wuxi, Zhu Qinfu was brought up by his Daoist uncle Zhu Xiuting 朱秀亭. He became the fifth generation of Daoists in the family, taking part in rituals from the age of 8 sui, and training formally with Zhu Xiuting from 12 to 16 sui. He was part of the Tianyun she group that performed for Henry Eichheim in 1921.

Around 1940 he formed a band called Shiwuchai 十勿拆, renowned for their rendition of the Shifan gu instrumental repertoire. In October 1947 he was invited by the Yangchun she in Shanghai to combine with the Tianyun she for three days of performances, attended by luminaries like Mei Lanfang and Yu Zhenfei. The recordings were broadcast and issued on six discs, but were apparently destroyed in the Cultural Revolution.

After Liberation, Zhu Qinfu was recruited in 1952 to the orchestra of the Central Opera Academy in Beijing, and then the Central Experimental Opera Academy. In 1962 he was sent back home as a result of the state cuts following the famine—whereupon, to their credit, the conservatoires of Shanghai and Beijing employed him (the CD-set Xianguan chuanqi includes a 1962 recording). But with the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution he was again forced home.

In 1978 the Shanghai conservatoire once again sought him out. Their recordings were less than ideal, since he was no longer in good health. In 1979 they made a TV documentary. Zhu also returned to the Central Conservatoire in Beijing before his death in 1981.

Back in Suzhou, Liu Hong also introduces two leading liturgists:

Xue Guiyuan 薛桂元 (b.1919) began learning with his father from the age of 9 sui, training from 15 sui at the Anzhaiwang miao 安齋王廟 and from 19 sui with Shao Shilin 邵世琳. Whereas the most accomplished Daoist instrumentalists might find work in state troupes, this was not an option for ritual masters like Xue Guiyuan, and from 1951 he had to work as a peasant, right until 1988 when he was summoned to the Xuanmiao guan.

Zhang Boxu 張伯旭 (b.1921), from Wuxian county, learned with his father from 9 to 13 sui, going to study with Li Duanchun 李端春 before making a living as a household Daoist. From 21 sui he spent two years in Suzhou under Lu Zifan 陸子範. He seems to have remained active until 1962, when he had to return to peasant life. Resuming ritual activities from 1988, he was recruited to the Xuanmiao guan in 1992.

Zhang Boxu, ritual transmission.

All these Daoists came from hereditary backgrounds, learning first in the family and then often with other masters. They had all performed rituals for their local communities before Liberation; though such accounts are unclear about their ritual life under Maoism, they had been largely unable to practice until the 1980s’ revival.

Cao Benye and Zhang Fenglin also introduce three able younger Daoists who became priests at the Xuanmiao guan since 1984, taking part in training sessions (cf. Shanghai) and becoming regular members of the temple’s main ritual group: Lu Jianzhong 陸建中 (b.1966), Xie Jianming 謝建明 (b.1971), and Han Xiaodong 韓曉東 (b.1972). Here we can note a shift: with hereditary training having been disrupted, their studies now took place at a later age, and under the auspices of the temple’s training programmes. Lu Jianzhong and Han Xiaodong went on to pursue their studies further with ritual master Xue Guiyuan.

But again, I wonder about the fates of Daoists struggling to make a living after Liberation: not only the more accomplished fashi ritual masters and instrumentalists, but ordinary Daoists too. Many had to return to the collective fields or take up factory jobs, though doubtless some also performed rituals intermittently. More detailed biographies would yield rich material on the Maoist era.

Xuanmiao guan group led by Zhou Zufu (centre, drum), Beijing 1993. My photo.

Today the Xuanmiao guan group comprises some accomplished Daoists (see also here), but the temple’s “museified” official representation may innoculate us from considering the complex realities of local ritual life (cf. the Zhihua temple in Beijing). We still need to include the lives and activities of both fashi ritual masters and ordinary Daoists in the picture.

6 Film

I return to my usual refrain: none of this discussion can convey an adequate impression of the actions and sound of rituals in performance—and sound is precisely the means by which the texts are communicated.

So beyond silent immobile texts (and beyond transcriptions, or even audio recordings), what we need is films. After all, fieldworkers do commonly film the rituals they observe; but their footage is rarely admitted to the public domain. Online you can find a few unedited, undocumented clips, like the footage of the Dispatching the Talismans at the end of this post.

Rather, I’m suggesting edited ethnographic films with commentary and subtitles showing liturgical texts—both documentaries showing ritual life in social context, and “salvage” projects aiming to preserve or recreate rarely-performed rituals. For the former, Ken Dean’s film Bored in heaven enriches his detailed work on ritual life in Putian in Fujian; for the latter, we might cite the current project of the Shanghai Daoist Association, and Patrice Fava’s films tend towards this style. For further such material, see here.

Of course, the historical dimensions of film may be rather shallow. It by no means supplants textual publications, but it should be a sine qua non. However well such textual descriptions are done, they can’t begin to evoke such complex rituals; it’s an absurdity of academia that they are considered adequate. Film is hardly a new medium. Scholars’ reluctance to use it may be partly to do with the lasting dominance of print media in academia, but it also suggests that they consider the written text, not performance, as primary. They write texts about other written texts. In the Appendix of my Daoist priests of the Li family I made this analogy:

It’s like someone with a fine kitchen and loads of glossy cookbooks, who draws the line at handling food or cooking.

If a copy of the 1956 film of the Suzhou Offering ever miraculously resurfaces, then Tao Jin can add subtitles for the ritual segments and vocal texts…

* * *

So the Xuanmiao guan is just one element in Suzhou Daoist ritual; and the latter is just one component of ritual life around the region.

A certain compartmentalization of all these strands may be inevitable; but it’s hard to bring them into dialogue. I suppose it was this kind of synthesis that I attempted in my work on the Li family Daoists in Yanggao, combining text and film. Within the ethnographic framework of the book I gave material both on the wider history of their ritual texts and on their changing performance practice—my task made easier by the sparser historical material and a smaller ritual repertoire. Often my posts on local ritual in north China concern traditions for which little evidence has emerged in either historical or religious studies—which makes them both valuable and limited. But for regions like Suzhou it may be too much to ask for an accessible synthesis of these various elements.

So again the analogy of “blind people groping at the elephant” seems apposite.

With many thanks to Tao Jin and Vincent Goossaert

[1] On the Longhushan connection, see e.g. Vincent Goossaert, “Bureaucratic charisma: The Zhang Heavenly Master institution and court Taoists in late-Qing China”.

[2] “Dagaoxuandiande daoshi yu daochang: guankui Ming–Qing Beijing gongtingde daojiao huodong” 大高玄殿的道士与道场:管窥明清北京宫廷的道教活动, Gugong xuekan 2014.2, and

“Dadong wushang jiuji tianxian chuanjie keyi chutan: yige Qingdai Beijing yu Jiangnan wenhua luantan jiaohu yingxiangde anli” 蘇州無上九極天仙傳戒科儀初探: 一個清代北京與江南文化亂壇交互影響的案例, Daoism: religion, history and society 5 (2013).

[3] Johnson, “Two sides of a mountain”, pp.95–6.

[4] My summaries here are based on three sources, not always unanimous in detail: the Anthology, Cao Benye 曹本冶 and Zhang Fenglin 張鳳麟, Suzhou daoyue gaishu 蘇州道樂概述 (2000), pp.131–40, and Liu Hong 刘红, Suzhou daojiao keyi yinyue yanjiu: yi “tiangong” keyi weili zhankaide taolun苏州道教科仪音乐研究:以“天功”科仪为例展开的讨论 (1999), pp.321–8.

[5] Cf. my Folk music of China, pp.255–6.

By this time

By this time

Xuanjuan scriptural group, Jingjiang 2009.

Xuanjuan scriptural group, Jingjiang 2009. Rituals performed by Tao Jin’s master Zhou Caiyuan in July 2011, showing locations, personnel, ritual type, and ritual segments. For the seven rituals held at the Heshan daoyuan he was a “guest master” (keshi 客师).

Rituals performed by Tao Jin’s master Zhou Caiyuan in July 2011, showing locations, personnel, ritual type, and ritual segments. For the seven rituals held at the Heshan daoyuan he was a “guest master” (keshi 客师). Rituals held at the Chenghuang miao temple in July 2011, including Communal Offerings (gongjiao), Crossing the Passes (guoguan), commemorative daochang, and so on.

Rituals held at the Chenghuang miao temple in July 2011, including Communal Offerings (gongjiao), Crossing the Passes (guoguan), commemorative daochang, and so on.

Apart from the usual suspects like the Bhagavad gita, Eliade, Castaneda, Jung,

Apart from the usual suspects like the Bhagavad gita, Eliade, Castaneda, Jung,

Still, even photos of ritual practice remain silent and immobile. Given that ritual is

Still, even photos of ritual practice remain silent and immobile. Given that ritual is

So while there are complex issues at work here, the recent directive illustrates a common befuddled knee-jerk response from local government. If they’re so keen on harking back to Maoist values, they might instead consider a re-education campaign for cadres—it is they who now lead the way in “vulgarity” and

So while there are complex issues at work here, the recent directive illustrates a common befuddled knee-jerk response from local government. If they’re so keen on harking back to Maoist values, they might instead consider a re-education campaign for cadres—it is they who now lead the way in “vulgarity” and

.

.

Shawm players from Mizhi county, assembled for a regional festival in 1981.

Shawm players from Mizhi county, assembled for a regional festival in 1981.

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997.

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997.

In Wuxi, under the tuition of the American missionary

In Wuxi, under the tuition of the American missionary