Right: Bruce Jackson with Diane Christian.

Among all the numerous tomes on fieldwork (and numerous posts under said category), I keep recommending

- Bruce Jackson, Fieldwork (1987)

(e.g. here, and recently in this post on Doing fieldwork in China), so I thought I should re-read it, and give a little introduction. Purely incidentally, I’m very keen on one-word titles—for a less succinct citation, see here, under Jarring.

Part One: Human matters opens with a chapter on ways of doing fieldwork. He wonders:

What did Alan A. Lomax do when his informants sang songs he didn’t like? What did he say and do when they interspersed in their folksy repertoires songs they learned from the radio or the jukebox?

To be fair, fieldworkers do now tend, consciously, to include such material. But folklorists, unlike scientists, rarely report on their failed experiments—Jackson cites Charles Keil on the Tiv; we might add Nigel Barley in Cameroon, and even my 2018 trip in search of Chinese village temples. As Jackson was writing, the literature also rarely betrayed personal opinions of the fieldworker. While noting exceptions like James Agee’s Let us now praise famous men, Jackson cites John M. Johnson:

It is impossible to review the literature about methods in the social sciences without reaching the conclusion that “having feelings” is like an incest taboo in sociological research.

Again, more recent work has partially rectified this tendency (e.g. Kulick and Willson, eds, Taboo: sex, identity and erotic subjectivity in anthropological fieldwork, or Barz and Cooley eds, Shadows in the field, or indeed Barley). By the way, I also like Barley’s comment on how fieldwork enables one to assess the monographs of others:

Henceforth […] I would be able to feel which passages were deliberately vague, evasive, forced, where data were inadequate or irrelevant in a way that had been impossible before Dowayoland.

Jackson takes us through the various conceptual and mechanical stages of planning. As to the work of collecting “in the field”, he notes the move from acquiring disembodied texts towards documenting their whole social context. In his early days he collected variants of the song “John Henry” as if they had some kind of autonomous existence, but he soon became wary of lofty context-free academic discourses on “meaning”. He gives a nice list of questions, that would be useful for collectors of Chinese folk-song:

- Where and when and from whom did you get that song?

- Did you change it? If so, how?

- Are there other versions you like less or more? What and whose are they and why do you feel the way you do about them?

- What’s the song about?

- What else is it about?

- What do you think about that story?

- Do you think about that story?

- When would you sing it?

- When do you sing it now?

- If you don’t perform the song, do you know it? If you know it, why don’t you perform it?

He cites worthy early advocates of such an approach, from Ben Botkin (1938) to Peter Bartis (1979) and the archaeologist William Sturtevant (1977), noting the difference between formal interviews and informal observation:

You can often learn more from what happens to be said and done in your presence than you can from what’s said and done in response to your questions or requests.

Still more succinctly, he summarises:

What sorts of things do people do? What sort of sense do they make do the people doing them?

Discussing salvage folklore, he reflects wisely on the age-old sense of urgency about “rescuing” traditions:

It’s always too late to capture such things. Aspects of culture being changed can never be seen by the visitor for or as what they were. We can learn things of value by trying to discover what’s been lost, but the knowledge is never more than partial—exactly as all historical enquiries can never give us knowledge that is more than partial. The world of our forebears will never be ours. […]

Salvage folkore can be valuable, but only if the collector understands the place the information collected plays in the lives of the people supplying the information.

He goes on:

The heart of the salvage folklore operation is to rescue from oblivion some art or artefact or piece of knowledge. That’s a perfectly legitimate reason for doing fieldwork: those songs or stories or legends or folkways or folk arts are part of our heritage, part of what makes our world what it’s become, and they should be preserved for exactly the same reasons works of literature or sculpture or letters of prominent persons or old city maps should be preserved. Knowing such facts helps us understand cultural adaptation and change. The reason few folklorists do salvage folklore nowadays isn’t because they’ve all decided such preservation is useless; rather it’s because the definitions of folklore and the folk process have expanded in ways that permit folkorists to deal with modern life and with traditions, processes, and styles that are very much alive.

By now the ideology of salvage may have been widely downgraded, but it remains common in China today, both among Chinese and foreign scholars: such issues of context hardly feature in the accounts of scholars in search of Daoist ritual manuals or seeking to record “ancient music”.

Jackson discusses the multiple ways of finding “informants” (a term to which he resigns himself more readily than I do). Indeed, in China I’ve noted that rather than making platitudinous visits to the county Bureau of Culture, more useful sources of local information might come from chatting with the boss of a funeral shop, or stopping to chat to an old melon-seller by the roadside. For the broad range of my own mentors in Yanggao, click here.

Jackson reflects on more and less successful field trips. He reminds us that the “facts” of our data collection, and indeed the way we use the mechanical equipment we bring to the field, are subjective.

I take part in the New Year’s rituals on yunluo gong-frame, Gaoluo 1998.

In Part Two: Doing it, Johnson clarifies the notion of “participant observation” (which again is less common among Chinese fieldworkers):

Participant observation means you’re somehow involved in the events going on, you’re inside them. You might, like Bruce Nickerson (1983), study factory work by taking a job in a factory; or, like William Foot Whyte (1943), you might take up residence within the community you want to study. You might go drinking or fishing or picnicking or campaigning with the people whose folklore concerns you.

He notes the ethical questions that this poses:

Each variation of the participant-observer role requires some measure of trust—in exchange for which the fieldworker has responsibilities more complex than those of the complete outsider.

More recently Sudhir Venkatesh‘s work with Chicago street gangs provides a particularly troubling instance of the dilemma. Jackson cites Edgerton and Langness (1974):

Complete involvement is incompatible with the anthropologist’s primary goals, but complete detachment is incompatible with fieldwork. Successful fieldwork requires a balance between the two, a balancing act which is every bit as difficult as it sounds.

He notes that with folklorists now working more often in industrial societies than among those whose life cycle is based on the agricultural calendar, they are more flexible in options than anthropologists, and more ranging in concern than oral historians. For China, while a year-long stay is routine among Western-trained anthropologists such as Liu Xin or Adam Yuet Chau, scholars more commonly make shorter visits over a long period.

Fieldworkers are always working in contexts of their own devising, whether as hidden observers or asking individuals to perform. There is […] nothing wrong with this, so long as the fieldworker understands the nature of the devised context, knows how it limits the information provided and how it infuences the behaviours of the informants. Fieldworkers deal with real people in real situations, and they must, therefore, understand the ways their presence influences what’s going on. They must be sensitive to the kinds of relationships they develop with the people who may agree to perform for them, and they must understand that the rhetorical form called “the interview” is different from ordinary discourse in critical ways.

Gaoluo: left, my famous haircut, 1993;

right, maestro Cai An introduces Wu Fan to the wonders of singing the gongche notation in preparation to realize it on the shengguan ensemble, 2003.

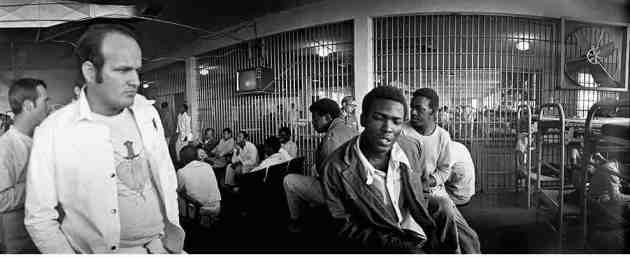

This leads to Chapter 6, where Jackson discusses the crucial issue of rapport. Mentioning “stranger value”, he discusses “why people talk to you”, and the pros and cons of payment. He recommends Jean Malaurie’s The last kings of Thule, and cites Charles Keil’s Tiv song; he tells stories about working with Pete Seeger at a black convict prison in Texas in 1966 (see below), and later at an Arkansas prison; and he tells how his mother defused a threatening incident while working as a nurse in a mental hospital. At a tangent, you may enjoy this post on my own run-ins with the local constabulary in China.

In Chapters 7 and 8 he discusses interviewing and ordinary talk in turn.

Having a conversation about a part of life and interviewing someone about a part of life are not the same kinds of event; they’re not even the same kinds of discourse. […]

The best interviewers somehow make the difference between conversation and interview as unobtrusive as possible.

We all adapt constantly, “code-switching” naturally:

I automatically adopt different styles and levels of discourse when talking to one of my classes, to a police officer who insists I was exceeding the speed limit, to an auditorium full of strangers, to my family at home, to my mother, to someon who owes me money, to someone I owe money. You do the same thing. None of these styles is necessarily dishonest or phony; most of them are what seems appropriate for the situations in which they emerge.

Listening to tapes of his interviews Jackson learns that he talks too much. And he finds that one can’t always record everything on tape: sometime it may interfere with the occasion.

Have a good time. Tell yourself to remember as much as you can and be sure to take notes later. Sometimes it’s okay just to be a person.

He describes his experiences in compiling A thief’s primer (1969), based on interviews, and chats, with a Texan check-forger and safecracker called Sam, as well as his search for supporting material from others.

More useful advice:

Many times slight rephrasing of a question puts it in a form that demands a discussion rather than a word. Instead of “Did you like what he said” ask “What did you think about what he said?” Instead of “Did you always want to be a potter?” ask “How did you become a potter?”Instead of “Have you heard other versions of this song? ask “What other versions of this song have you heard?” […] Putting the question in a way that elicits discussion rather than a single word gives the subject a chance to talk, and it indicates that you value the response. […]

Part of the task is being sensitive to the rhythms of utterance. Native New Yorkers, for example, rarely have notable pauses in their conversations; when pauses occur, other speakers usually leap in. Native Americans frequently have pauses; leaping in is rude. […]

Often the most interesting responses are produced by follow-up questions—questions you ask after you get the first answer. The follow-up question interrogates the response itself; someone tells you what was done, the follow-up asks why it was done, or why it was done that way, or when and how often and by whom it was done; someone tells a story, the follow-up asks what the teller thinks the story was about, and whether the teller believes it, and whether the teller heard it any other time.

Moving on to “ordinary talk”, Jackson notes the usefulness of listening to people talking among themselves.

The lengthy Part Three: Mechanical matters largely concerns technical guidance on the equipment that one takes to the field, and the production of related outputs. Though, strangely, this was Jackson’s main original purpose in writing the book, such advice (also a regular feature of ethnomusicological handbooks) is inevitably ephemeral. Still, this section is interspersed with useful, more enduring comments on our own role and interaction with our subjects.

These insights feature prominently in the opening chapter, “Minds and machines” . Here he first ponders “what machines do for you and to you”. He recommends a sharp eye and a good memory, along with pen and paper. As he notes, the latter are unsatisfactory for interviews, detracting from engaging fully with one’s subject. But using recording equipment has similar flaws, such as “field amnesia”. Jackson discusses teamwork and division of labour, noting that the fewer outsiders intrude, the better.

My fieldwork colleague Xue Yibing chats with an elderly former Daoist in an old-people’s home, and with a young ritual recruit, early 1990s.

Even I began to take Jackson’s points on board with my work on Gaoluo village, and later on the Li family Daoists. In Gaoluo I worked with one, sometimes two, Chinese colleagues, with them taking notes affably while I thought of irritating etic questions and distributed cigarettes (the latter deserving a major chapter in any fieldwork guide to China). By contrast, with the Li family Daoists since 2011 I’ve mostly managed on my own. Jackson suggests taking only as much equipment as you really need. Given that I rarely care to make audio recordings of my chats, I’ve had to develop a way of maintaining engagement while taking notes; sometimes while engaging fully, with my notebook to one side, I sheepishly go, “Hang on a mo, I gotta get this down!”

Relaxing in the scripture hall between rituals, Daoists Golden Noble and Wu Mei amused by my notebook. I know I use this photo a lot (e.g. here), but I really like it!

In detailed chapters (much of whose fine technical detail has inevitably become obsolete), Jackson then discusses recording sound, microphones, photography, and video (useful tips here). He notes the different purpose of such work (as art, and as diary), as well as the subjectivity of the eye and ear. In Chapter 15 “Records” he discusses the work of documenting one’s material in logs—along with fieldnotes, an important supplement to fragile memory.

Part Four: Ethics, consists of the chapter “Being fair”—“the most important thing of all”. Jackson covers the role of the fieldworker both in the field and later, publication in various formats, and the thorny issue of ownership, rights, and payment, much discussed since, as “communal ownership” of folklore material came to be questioned. He cites the case of the Lomaxes’ recordings of Lead Belly—who was among the first convicts they recorded in Louisiana State Penitentiary in 1933, long before Alan Lomax went on to work with Jackson.

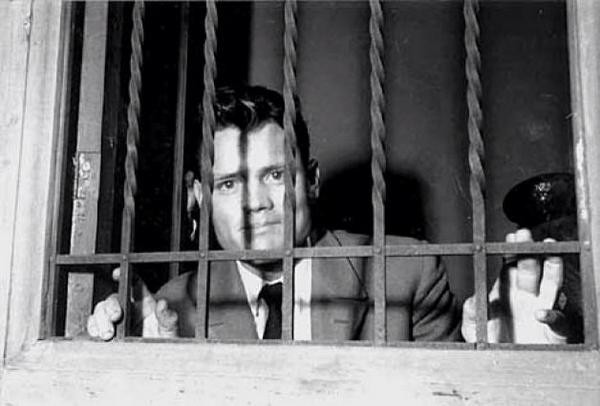

Inside the wire: Cummins, Arkansas.

In the Appendix on Death Row Jackson ponders issues surrounding his major work with Diane Christian in prisons in Texas and Arkansas. Here’s a trailer for the 1979 documentary Death Row (1979):

Jackson explains his initial fear of being voyeuristic, and the complex issues of gaining a degree of trust.

Some men talked because they wanted people to know what the place was like. Some talked because we gave them a chance to vent their grievances against the criminal justice system or the prison administration or other inmates of the row. Some talked because they thought the film might do some real good.

And he quotes Rosalie Wax:

It would be gross self-deception not to admit that many informants talked to me because there was nothing more interesting to do.

As he observes, there is no such thing as a neutral observer. And

all reconstructive discourse—a statement by a murdere waiting in a tiny cell in Texas, the autobiography of Henry Kissinger, the letter of a lover to a lover who is presently angry—is craft.

Following Jackson’s book Wake up dead man (1972), here’s an excerpt from his 1994 CD of recordings of Texas convict worksongs:

And this site has useful links to his work with the Seegers at Huntsville prison in 1966. In Chapter 6 he tells how Pete Seeger overruled Jackson’s doubts about the value of him playing for the inmates, resulting in “one of the best concerts I ever heard or saw”—and substantial gains in trust. I pause to reflect how hard is to imagine a similar fieldwork project for Chinese or Russian prisons. Meanwhile Johnny Cash was also finding how popular his prison concerts were.

* * *

While music plays a quite minor part in Jackson’s book, he came to folklore through an early interest in folk-song. Among the tasks that George List gave him in the Archive of Folk and Primitive [sic] Music at Indiana University was preparing the master tape for the 1964 Folkways LP of Caspar Cronk’s recordings in Nepal—mainly of Tibetan songs.

* * *

Many of Jackson’s approaches have since become standard; some of his comments might seem obvious, but they’re always right on the nail. And as with Bruno Nettl, it’s his engaging style that appeals to me; just as he stresses human rapport in fieldwork, he seeks to communicate in his style of writing—not always an academic priority, to put it mildly. The reader can tell that he really cares about both the work and the people he consults, and that he finds such projects important and inspiring.

The Royal College of Music, London.

The Royal College of Music, London.

Cellist, Shanghai Conservatoire, 1986. My photo.

Cellist, Shanghai Conservatoire, 1986. My photo.

Thomas Hart Benton, The sources of Country music (1975).

Thomas Hart Benton, The sources of Country music (1975).