At the heart of the funeral sequence of the Li family Daoists today is the Invitation ritual (zhaoqing 召請). This introduction is adapted from my book, pp.109–12, 298–307—and do watch the film from 58.14. For audio segments, click on ##1–3 of the playlist in the sidebar (commentary here). See also Translating Daoist ritual texts.

This is another illustration that ritual manuals don’t tell the whole story—performance is primary.

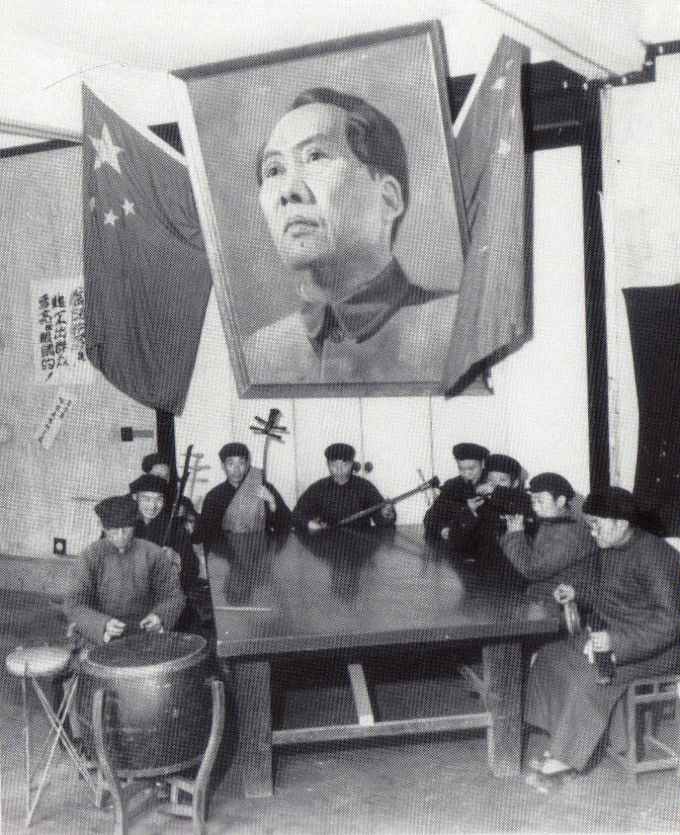

Fig. 1: Li Manshan performs the Invitation, 2009

I have two reasons to focus on the Invitation—one about simplification, one about complexity. This is one of the few ritual segments for which the Daoists still have a manual, although as usual they don’t need it in performance. It is among the longest in their collection, but they now perform only a small part of its nineteen double pages; as with Fetching Water, a comparison of their present performance practice with the manual shows a significant simplification. Perhaps the term “complete” in the title Zhaoqing quanbu suggests that it was commonly abbreviated. But only rarely can we speculate how long it may be since they used more of its text.

As to complexity, whereas today the bulk of their performance of funerary texts consists of slow choral hymns, for this Invitation sequence the a cappella rendition over a mere fifteen minutes or so is now perhaps their most densely-packed, complex, and varied segment of ritual performance, full of dramatic contrasts in tempo and dynamics—with both slow and fast choral singing and chanting, free-tempo solo singing, and a variety of styles of percussion interludes and accompaniment.

The Invitation was also a major section within the lengthy nocturnal yankou ritual, both here and in the great temples. For two-day funerals now, with the yankou anyway obsolete, the Invitation has evolved into a public ritual at dusk before the evening session of Transferring Offerings. Whereas even in the early 1990s many village onlookers accompanied the kin, creating more bustle, now it is largely a private ritual for the kin.

The sequence

First, as the Daoists arrive at the soul hall, Golden Noble faces the coffin to recite a seven-word quatrain solo.

The manual opens with the quatrain “Sandai zongqin ting fayan 三代宗親聽法言”:

Let the three generations of ancestors hear the dharma speech,

Paying homage to the previous souls by burning paper money.

May the dharma speech open up the road to the heavenly hall,

To invite the deceased souls to attend the jasper altar.

Fig. 2

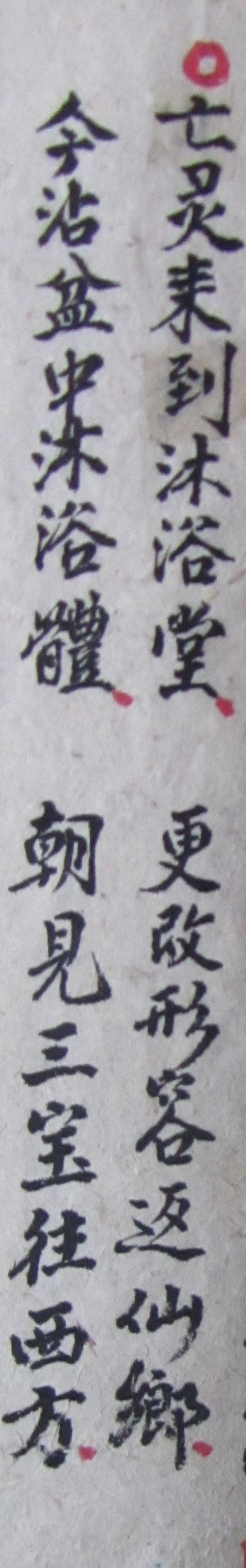

But instead Golden Noble recites another shuowen introit—which appears on the last page of the manual. That is how he learned from Li Qing, and it does the job just as well:

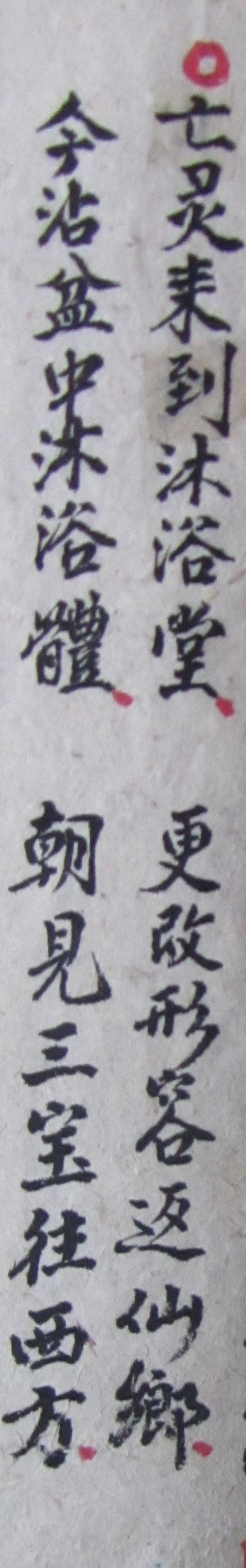

May the deceased souls come to the Bathing Hall, [1]

Transforming their shape and countenance to return to the immortal realm.

Now dipping into the bowl to bathe their bodies,

For an audience with the Three Treasures on the way to the Western Quarter.

Golden Noble then calls out “Proceed together, led by the Dao” (tongxing daoyin 同行道引), as shown at the end of the opening quatrain of the manual. If we didn’t know by observation, that would be a clue that while the preceding quatrain was performed at the soul hall, the remainder of the manual is to be performed on arrival at the site on the edge of the village.

Hereby Shaking the Bell

The next section in the manual, no longer performed, is Hereby Shaking the Bell (Yici zhenling 以此振鈴). One of several Yici zhenling texts that are a common part of the temple yankou, this slow sung hymn may also be used for other rituals, such as Delivering the Scriptures and Transferring Offerings—although the Yanggao Daoists no longer use it there either.

Song in Praise of the Dipper

Once they reach the site at the edge of the village, the altar table is set down, and the kin kneel in two rows in front of it while the Daoists stand in two rows behind it. Golden Noble presides, wielding flag, bell, and conch as he stands facing the kin. After a short percussion prelude with blasts on the conch, the first text now performed is Golden Noble’s solo chanting from the section of seven-word couplets opening Xinzhi jiguo 心知己過. Now he usually only chants the last two of the six couplets in the manual:

Fig. 3

I am the one to report the declaration of the procedures at the Jade Capital,

Vowing to save all beings and emerge from the web,

So the deceased soul may be born in the upper realms,

We sing in unison the Song in Praise of the Dipper.

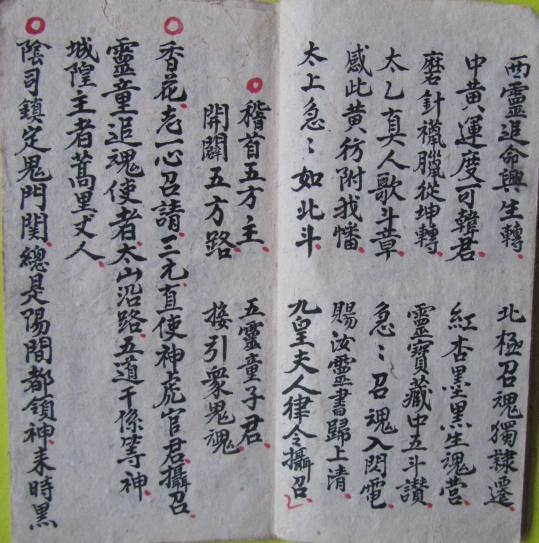

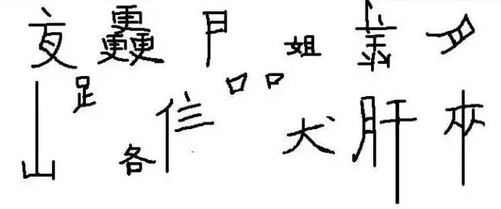

This indeed serves to introduce the Song in Praise of the Dipper (Gedou zhang), a slow choral hymn sung tutti a cappella. The title is to the Northern Dipper, otherwise not prominent in their funerary texts, explaining the respective responsibility of the five quarters for the salvation of the soul. Its seven-word couplets are each sung to the same melody; the short strophic melody has all the hallmarks of other hymns.

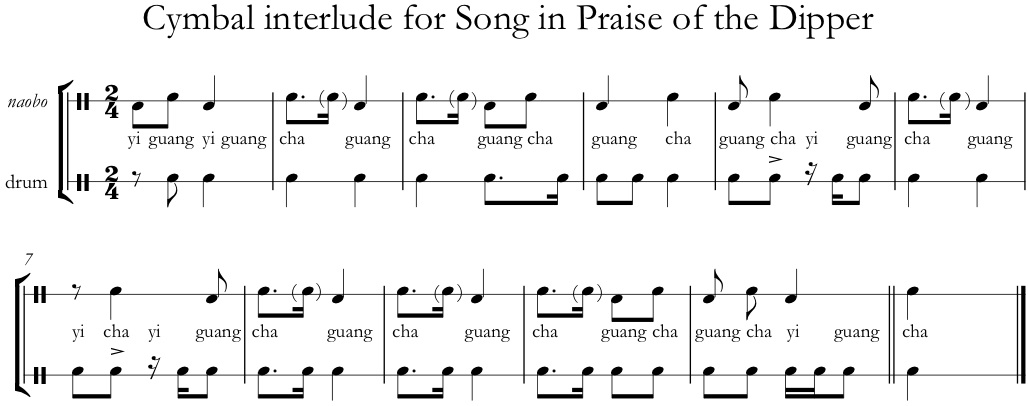

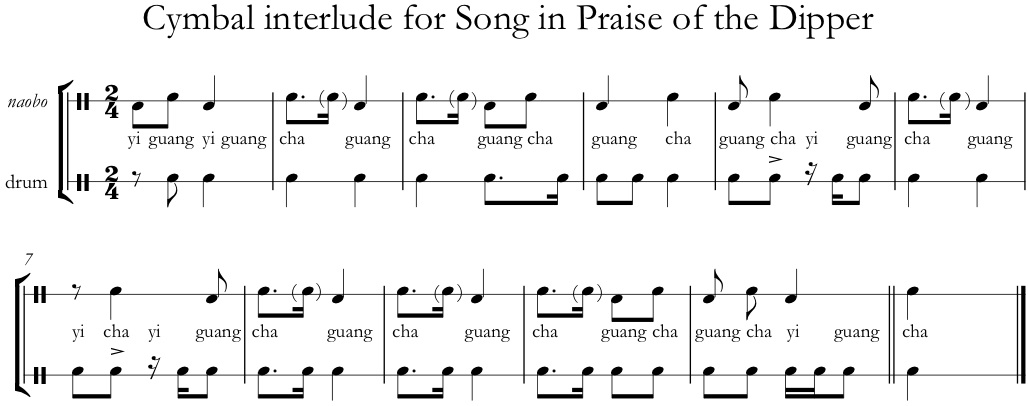

As each sung couplet ends, Golden Noble shakes the bell, waves the flag, and bows, as the other Daoists play a cymbal interlude—a variant of the pattern Qisheng 七聲 as notated by Li Qing, as you can see below from the tiny differences in the first and penultimate bars between the naobo line in practice and the Qisheng mnemonics. As ever, the line for the drumming, ever flexible, shows a typical version as played by Li Manshan.

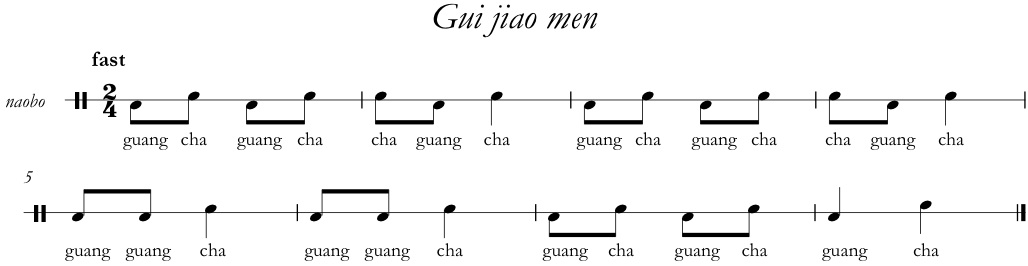

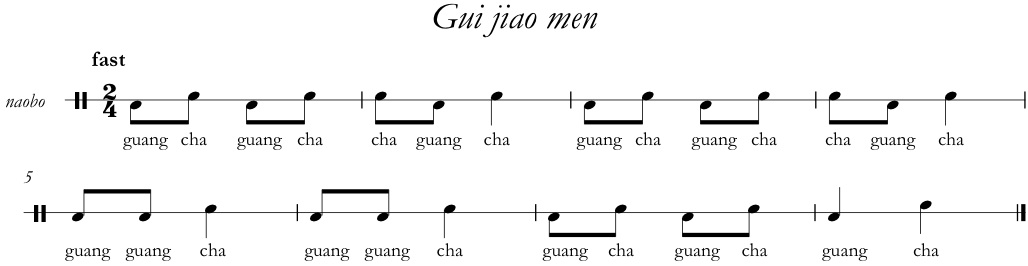

In recent years they tend to sing the hymn rather faster than they know it should go (you can hear a more majestic version in concert on track 1 of the audio playlist, and on the 2014 DVD). Anyway, with a very gradual accelerando over the verses, as they reach the seventh and eighth couplets they launch into fast isorhythmic chanting. They now play the fast cymbal interlude Gui jiao men (“Ghosts calling at the door”)—a pattern the same length as the processional Tianxia tong but differing subtly.

This leads into the five-word quatrain Jishou wufang zhu, sung tutti isorhythmically to a simple descending melody, without percussion, now slightly less hectic:

Bowing to the lords of the five quarters,

The masters of the lads of the five spirits

Open up the roads of the five quarters,

Receive and guide all the ghostly souls.

Fig. 4

Then two sections summoning a roster of gods of the local territory—now accompanied by percussion, and punctuated twice by the Gui jiao men cymbal pattern—are chanted tutti, most hectically. Prepared by the instruction at the end of the Song in Praise of the Dipper (Great Supreme, in haste like the Northern Dipper!), and in extreme contrast with the long slow melismatic hymns that now dominate most rituals, this transitional sequence flies past as black clouds swirl, purple mists coil, with complex adjustments of style, tempo, and instrumentation. This too is a rare instance in Yanggao today of the kind of fast chanting commonly heard in south China.

The Invitation verses (playlist #1)

In abrupt contrast to this rousing climax, time now stands still as Golden Noble gently begins to sing a sequence of solo verses in free tempo, accompanied only by his shaking of the bell, with Li Manshan punctuating the phrases with a brief subdued pattern on drum. Li Manshan has let Golden Noble lead this ritual since about 2003; his solo melody is modeled on the way that Li Qing sung it. Even the way he repeats words in the opening phrase (Zhiyixin zhaoqing, yixin zhaoqing, zhaoqing) is distinctive, setting a contemplative mood. We are in the middle of barren countryside, far from the bustle of the village; as night falls, the main light comes only from the little piles of paper money burned by the kin. Notwithstanding interruptions at the end of each verse by a fast loud chorus with percussion, and periodic deafening explosions of firecrackers, this exquisite solo plaint perfectly reflects the desolation of the surrounding countryside where the ancestors are to assemble.

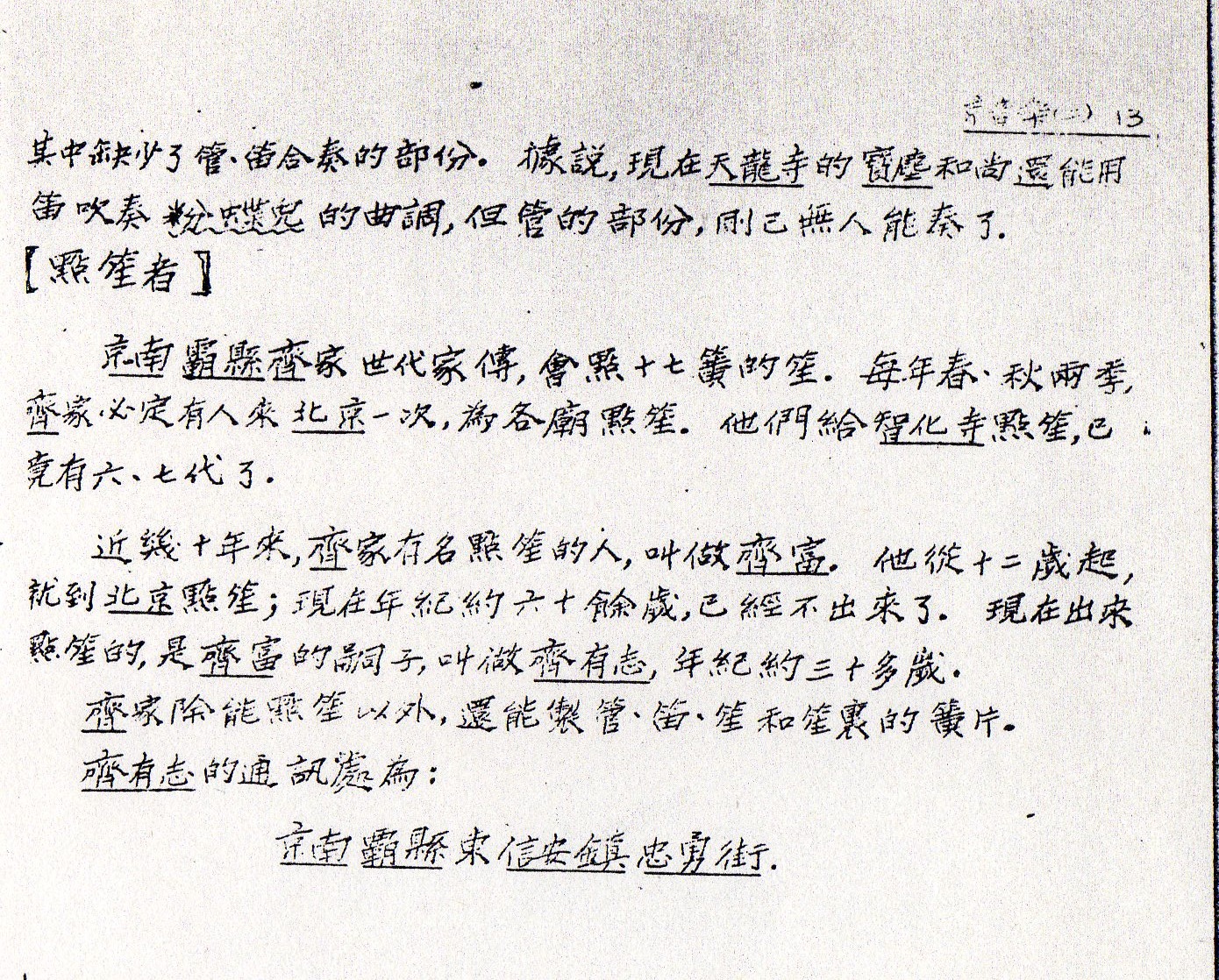

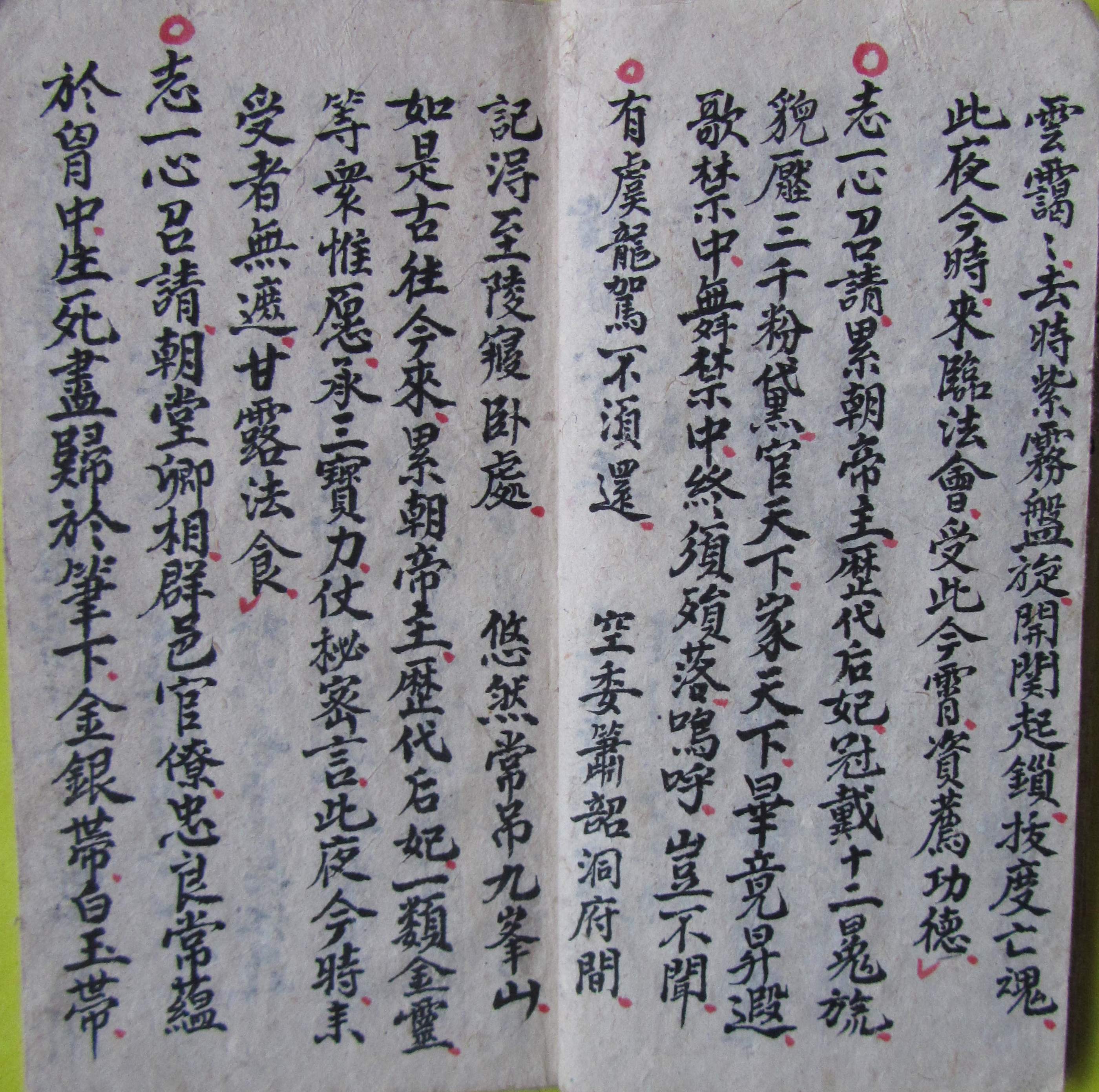

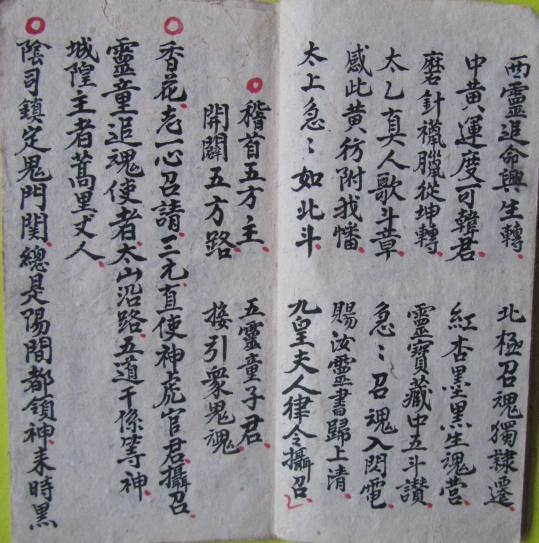

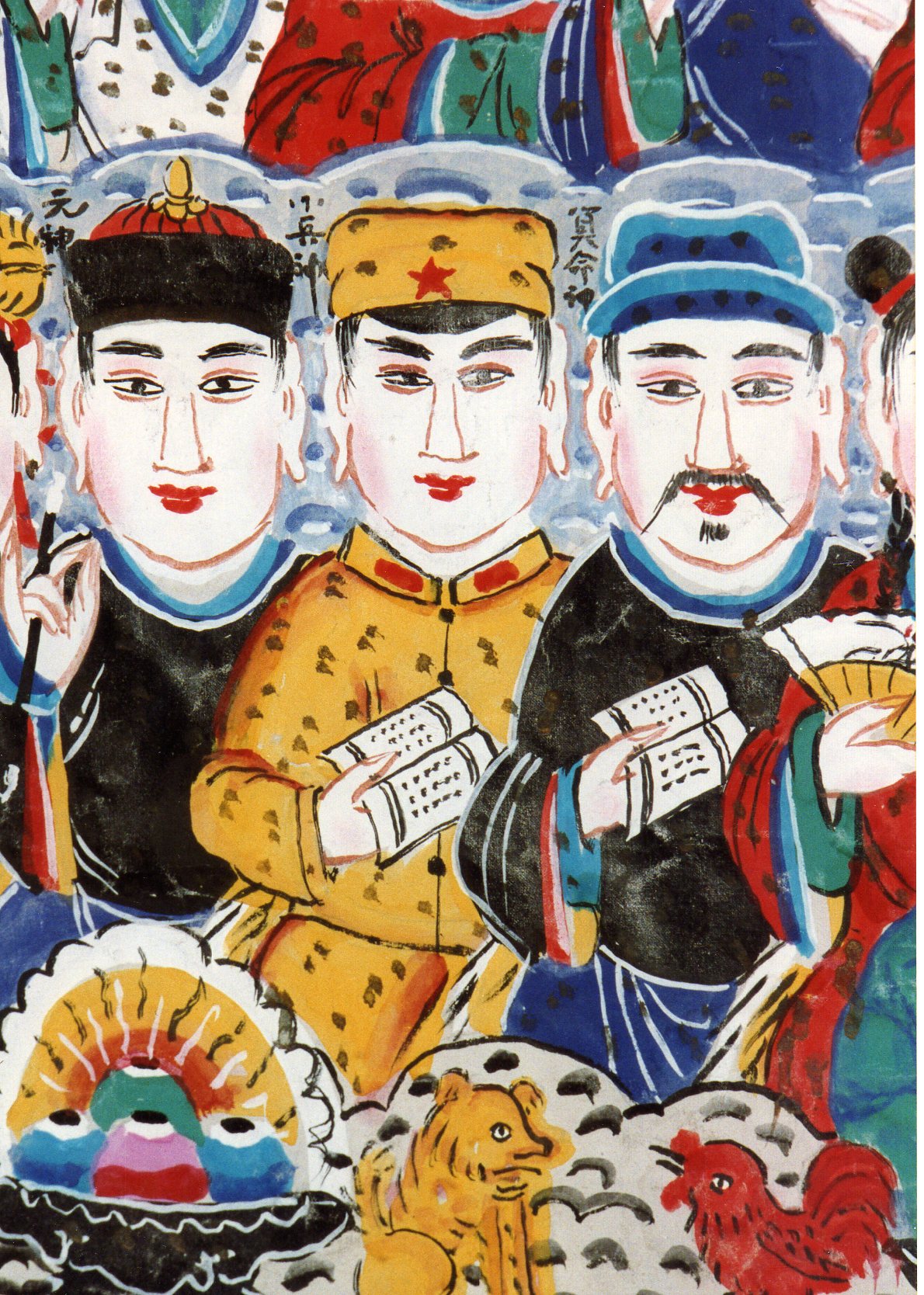

The twenty verses in the manual, each beginning “Vowing with hearts at one we Invite” (Zhiyixin zhaoqing), describe all kinds of occupations of the lost souls: emperors, ministers, generals, literati, sing-song girls, beggars, and so on. These verses are also found in the Li family’s Buddhist (not their Daoist) yankou manual—a sequence sometimes attributed to the great poet Su Dongpo (1037–1101). The twenty verses are now never sung complete; the chief Daoist chooses no more than six or seven of them. Both Li Manshan and Golden Noble agree that they should be performed complete, and were “in the past,” but even Li Manshan never heard the elders recite the whole sequence. To give an idea of the literary beauty of these texts, here is the opening verse (recto, lines 3–6):

Fig. 5

Vowing with hearts at one we Invite:

Emperors and lords of successive dynasties,

Empresses and concubines of epochs immemorial,

Bedecked in twelve-gemmed crowns,

Countenance outranking three thousand rouge-and-kohl belles.

All under heaven their remit, all under heaven their family,

Ultimately ascending.

Singing within the palace, dancing within the palace,

At the final moment they can only perish and fall.

Alas! Have you not heard?

Once astride the dragon of Yu they cannot return,

(tutti) In vain to deploy the Pipes of Shao within the Department of Caverns,

Fluttering the shadows and echoes, imperceptibly approaching!

But once rendered in exquisite solo melody, such textual beauty is multiplied.

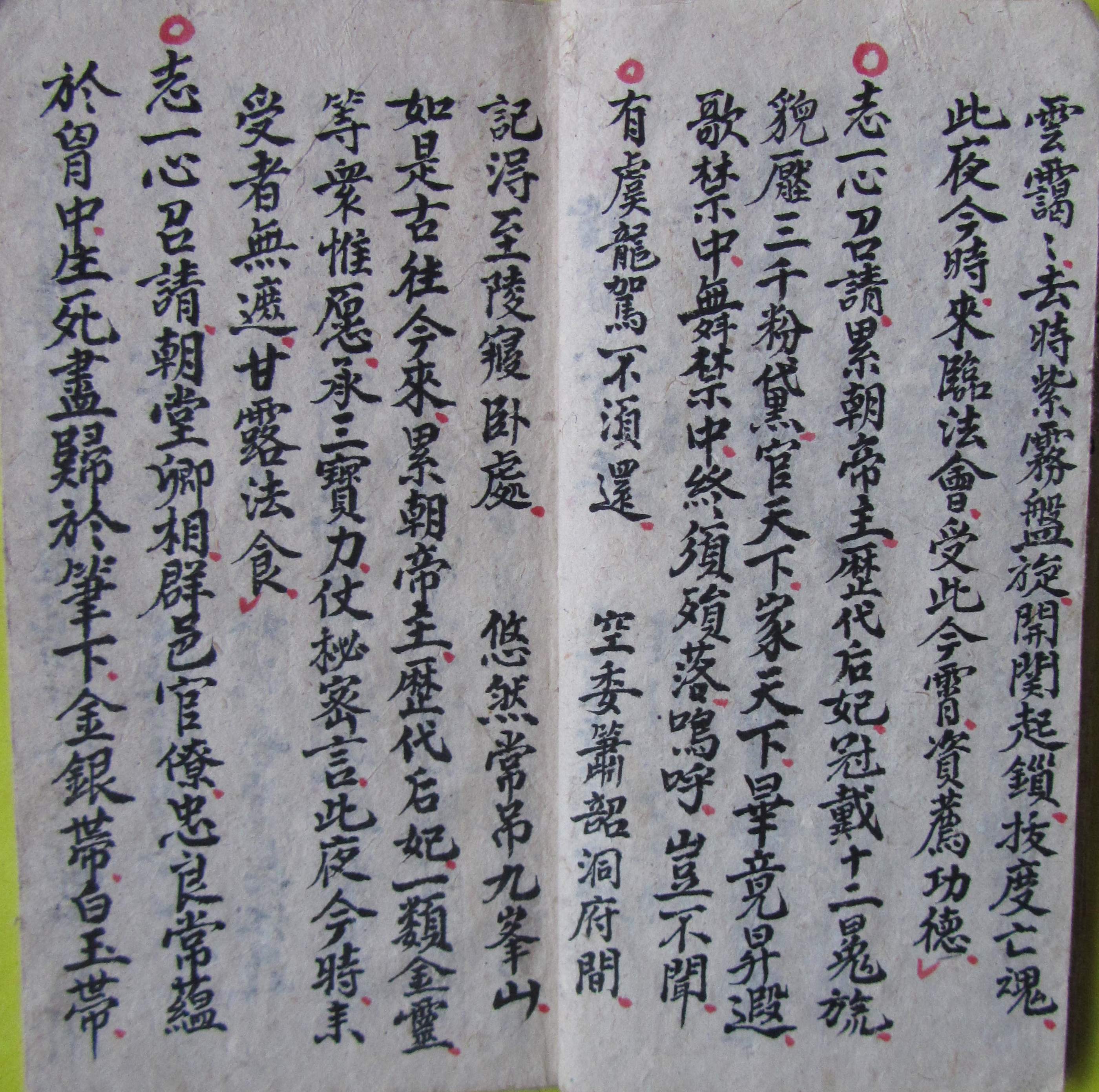

For the last two seven-word couplets at the end of each verse (last line of recto and first line of verso), the first is still sung solo, while for the second the whole group interjects to chant the text fast. But, then, instead of the manual’s elegant and long refrain (opening “And thus from time immemorial” Rushi guwang jinlai, 5th–3rd lines from end of verso above) confirming the invitation, they now substitute a single phrase “Fluttering the shadows and echoes, gradually approaching” (Piaopiao yingxiang ranran lailin 飄飄影響冉冉來臨), again sung tutti. This phrase is borrowed from the shorter sequence of a mere three Invitation texts from their other (“Daoist”) shishi manual.[2] It leads into another burst of the cymbal interlude Gui jiao men.

That is how Li Qing taught them, but they know that the two versions were once alternatives: when the older generation used the longer refrain, it was still sung solo, and they didn’t use a cymbal interlude. So using the Piaopiao phrase with cymbal interludes wasn’t Li Qing’s invention in the 1980s; but already by then, deciding that the full refrain was too long, they were generally adopting the shorter version.

Some other adaptations also have to be learned orally. In the Jinwu sijian section about the sun and moon, and again in the following verse “Gazing from afar on mountain hues” (Yuanguan shan youse), the name of the deceased has to be inserted, and another text replaces the tutti coda of the manual.

The Invitation verses in Beijing Buddhist ritual

I have to take it on trust that all twenty sections were once performed complete, including the longer refrain. The substitution of the “Fluttering the shadows and echoes, gradually approaching” phrase with cymbal interlude for the longer final refrain shortens the ritual a little; and the more recent practice of reciting only selected sections shortens it further.

Actually, the version as sung by the Li family in Yanggao is remarkably similar to that of Buddhist temples in old Beijing. In a fine initiative from the mid-1980s, the performance of the Buddhist yankou by former monks from popular temples in Beijing was recorded; later it was also transcribed and notated.[3] The Invitation sequence, virtually identical in text, is interesting.[4] All twenty sections were indeed performed for the recording. The text is divided between main and assistant cantors, both singing in free tempo with impressive beauty, accompanied only by the bell, the refrain of each section fast choral with drum. So again, it is worth pursuing temple links.

The Invitation memorial

When Golden Noble has finished singing the Invitation verses, first the short section Chenwen dadao 臣聞大道 (see Fig. 7 below) should be recited fast, either solo or tutti, with percussion, confirming the efficacity of the ritual in saving the deceased. This text is commonly omitted today.

Then (as specified in the manual, in red ink) Golden Noble presents the memorial. Having handed the bell to a colleague, who sounds it continuously, he takes out the folded document from his pocket, singing it solo in the same melodic style as the preceding “Vowing with hearts at one we Invite” verses, only more exuberantly, with muffled accompaniment on drum and small cymbals and occasional fast tutti choruses repeating a phrase. He unfolds each new section as he folds up the previous one—though he hardly needs to consult it except to check the names of the kin. In recent years, if the others start accompanying too fast on percussion then Golden Noble sometimes likes to corpse the others (especially his mate Wu Mei) by reading faster and faster, rolling his eyes rapidly up and down over the text.

The manual doesn’t contain the text of the memorial; it is not among the templates in Li Qing’s collection of ritual documents, and Li Manshan and Golden Noble write it from memory. Sometimes entitled Memorial of Rites and Litanies to Escort the Deceased (Songzhong lichan yiwen), it is addressed to the Court of Sombre Mystery for Rescuing from Suffering (Qingxuan jiuku si), and announces the details of the deceased and lists of the preceding three generations of kin. Generally Li Manshan writes the text first and fills in the names of the ancestors later when a member of the kin brings them to him. Dates, as always, are written in the traditional calendar.

Fig. 6: Invitation memorial, written by Li Manshan, Pansi 2011

Having sung the memorial complete, Golden Noble opens it out and hands it over to be burned by the kin, while the Daoists slowly and solemnly declaim a final five-word quatrain “Thousand-foot waves at Bridge of No Return” (Naihe qianchilang), another common temple text:

Fig. 7

Thousand-foot waves at Bridge of No Return,

Bitter sea myriad leagues deep.

If the soul is to evade the cycle of rebirth and suffering,

The Daoists are to recite the names of the Heavenly Worthies.

The return procession

So now after the document has been burned, if Redeeming the Treasuries is combined then the two treasuries are burned. The Daoists then lead the kin on procession back to the soul hall. Whereas the whole of the previous sequence has been performed a cappella, they now play shengguan all the way back while the kin burn paper to illuminate the way for the ancestors; on procession on the way out, they only use percussion because there is no-one to escort yet.

However, in Li Qing’s manual there follow thirteen verses for Triple Libations of Tea (san diancha). Li Manshan recalled these verses being recited on the route back, accompanied by Langtaosha on shengguan, but later they only played Qiansheng Fo without vocal liturgy. They still sometimes use a three-verse version for the solo introits in Presenting Offerings before lunch, and as a slow accompanied hymn for Transferring Offerings.

Even after the Libations of Tea were omitted, villagers used to “impede the way” (lanlu) on the return to demand popular “little pieces” from the Daoists, but by the late 1990s no longer did so—they now had plenty of other opportunities to hear pop music. Since around 2011 the kin often just stop occasionally to burn paper, not all along the route as they should. Altogether, the impetus towards simplification derives from the changing needs of the patrons.

The hymn at the gate (playlist ##2 and 3)

On the return to the soul hall, the Daoists now stand informally around the gateway to sing the Mantra to the Three Generations a cappella, as the kin again kneel and burn paper. This is the “Jiuku cizun” text in the manual. As usual, this a cappella version is sung faster than that with shengguan, though they retain the cymbal interludes. They round off the hymn with the fast percussion coda Lesser Hexi, and then lead the kin into the courtyard with a short burst of the pattern Tianxia tong. That is the end of the Invitation as performed today.

But in the manual, before the Mantra to the Three Generations, a further text Lijia quyuan 離家去遠 appears—also apparently a hymn, but unknown today. The volume then concludes with the solo recited quatrain that in current practice they recite at the initial visit to the soul hall; and then a final six-line hymn Qinghua jiaozhu, which should be sung (again, surely a cappella) while the oldest son kowtows.

Conclusion

One wonders how there was ever time for all the extra material in the manual, within what was once an even more busy ritual sequence throughout the day. The ritual in its present condensed form may have taken shape gradually, and it still makes a cogent and moving sequence that meets the needs of patrons.

Beyond just documenting which sections of text are performed today and which have been lost, we need to know how the texts are performed, and how Daoists adapt the material. It’s always hard to imagine the performance of ritual texts from the page, but here is a fine instance of variety. The text is rendered efficacious, and its drama heightened, through a varied yet cohesive sequence of slow solemn choral singing, hectic mantric choral chanting interspersed with percussion interludes, and exquisite free-tempo solo singing accompanied by conch and bell. Such a cappella rendition is of a different kind of complexity from the slow melismatic hymns that now form the bulk of their performance. Despite ritual simplification in modern times, the Daoists need to internalize complex rules—orally—in order to deliver the text efficaciously, animating it into a magical sequence.

[1] By the way, the Yanggao Daoists now have no separate Bathing (muyu) ritual, though it is part of the obsolete shezhao muyu ritual in Li Peisen’s funeral manual.

[2] It is used in the Summons (shezhao) ritual of the temples: Min Zhiting, Daojiao yifan 道教儀範 (Taipei: Xinwenfeng 2004 edn), p. 179.

[3] Ling Haicheng, Yuqie yankou yinyue foshi 瑜珈焰口音乐佛事 cassettes, with booklet (1986); Yuan Jingfang, Zhongguo hanchuan fojiao yinyue wenhua 中国汉传佛教音乐文化 (2003), pp.301–451, Yuan Jingfang Zhongguo fojiao jing yinyue yanjiu 中国佛教京音乐研究 (2012), pp.228–439. Cf. Chang Renchun, Hongbai xishi 红白喜事 (1993), pp.324–6.

[4] Yuqie yankou yinyue foshi, cassette 4b; Yuan Jingfang Zhongguo hanchuan fojiao yinyue wenhua, pp.389–395, Yuan Jingfang, Zhongguo fojiao jing yinyue yanjiu, pp.386–391.

In Wuxi, under the tuition of the American missionary

In Wuxi, under the tuition of the American missionary