*See also sequel here*

The experiences of Eastern European countries under state socialism, not to mention the Soviet Union and China, were all very different (see also Life behind the Iron Curtain: a roundup).

From a comfortable distance, looking at the GDR can seem voyeuristic, some kind of Stasi porn. But perhaps it’s more like “What would we have done?”—as Neil MacGregor asks in Germany: memories of a nation, full of insights on successive eras.

I guess I’m also trying to atone for my lack of curiosity as a touring muso on early trips to the GDR. In 1980 I played Elektra with Welsh National Opera in East Berlin and Dresden. With John Eliot Gardiner, in 1985 we did Israel in Egypt (see under Handel) in Halle, staying in Leipzig—apart from Michael Chance’s divine rendition of Thou shalt bring them in, my main memory is the whole orchestra and choir descending on Peters bookshop like locusts, to spend our over-generous Ostmark subsistence allowance (OK, unlike locusts) by buying up their entire stock of, ur, texts—sorry, I mean urtexts. In 1987 we did a memorable Matthew Passion in East Berlin (note also Hildi’s story).

My readings are also stimulated by my experience of China.

In Leipzig, I already mentioned the fine Forum of Contemporary History, and the Stasi Museum at the Runde Ecke is suitably disturbing. On the exceptional degree of surveillance under the Stasi, I can’t address the literature in German, but two books in English make useful introductions:

- Anna Funder, Stasiland, a brilliant piece of writing,

and

- Timothy Garton Ash, The file.

Garton Ash notes how Stasi is chasing Hitler fast as “Germany’s best export product”:

Ironically, this worldwide identification of Germany with another version of evil is a result of democratic Germany’s own exemplary commitment to expose all the facts about its second twentieth-century dictatorship, not brushing anything under the carpet. (229)

In 1979, when many Western observers were downplaying or ignoring the Stasi, I felt impelled to insist: this is still a secret police state. Don’t forget the Stasi! In 2009, I want to say: yes, but East Germany was not only the Stasi. (230)

The opening up the Stasi records had enormous consequences:

You must imagine conversations like this taking place every evening, in kitchens and sitting-rooms all over Germany. Painful encounters, truth-telling, friendship-demolishing, life-haunting. (105)

The file ponders the wider problems of writing about people’s lives, and memory:

I must explore not just a file but a life: the life of the person I was then. This, in case you were wondering, is not the same as “my life”. What we call “my life” is but a constantly rewritten version of our own past. “My life” is the mental autobiography with which and by which we all live. What really happened is quite another matter. (20)

He notes

the sheer difficulty of reconstructing how you really thought and felt. How much easier to do it to other people! (37)

The very act of opening the door itself changes the buried artefacts, like an archaeologist letting in fresh air to a sealed Egyptian tomb. […] There is no way back now to your own earlier memory of that person, that event. (96)

Now the galling thing is to discover how much I have forgotten of my own life.

Even today, when I have this minute documentary record—the file, the diary, the letters—I can still only grope towards an imaginative reconstruction of that past me. For each individual self is built, like Renan’s nations, through this continuous remixing of memory and forgetting. But if I can’t even work out what I myself was like fifteen years ago, what chance have I of writing anyone else’s history? (221)

Indeed, my process of writing about people’s lives in China has made me unpack the blurred lines of my own story.

As Garton Ash comes face to face with the people who had informed on him, he experiences constant moral doubts.

As I leave I can see in her eyes that this will haunt her. Not, I think, because of the mere fact of collaboration—she was, after all, a communist in a communist state—but because working with the secret police, being down in the files as an informer, is low and mean. All this is such a far, far cry from the high ideals of that brave and proud Jewish girl who set out, a whole lifetime ago, to fight for a better world. And, of course, there will still be the lingering fear of exposure, if not through me then perhaps through someone else.

I now almost wish I had never confronted her. By what right, for what good purpose, did I deny an old lady, who had suffered so much, the grace of selective forgetting? (129)

He notes the irony in the careers of West German academics:

Cultured, liberal men in their thirties or forties, they are scrupulous pathologists of history, trained on the corpses of the Gestapo and SS. Theirs, too, is a peculiarly German story: to spend the first half of your life professionally analysing one German dictatorship, and the second half professionally analysing the next, while all the time living in a peaceful, prosperous German democracy. (196)

West Germans, who never themselves had to make the agonizing choices of those who live in a dictatorship, now sit in easy judgement, dismissing East Germany as a country of Stasi spies. […]

Certainly this operation has not torn East German society apart in the way some feared it would. In an agony of despair at being exposed as a Stasi collaborator, one Professor Heinz Brandt reportedly smashed to pieces his unique collection of garden gnomes, including, we are told, the only known specimen of a female gnome. Somehow a perfect image for the end of East Germany. (199)

Two schools of old wisdom face each other across the valley of the files. On one side, there is the old wisdom of the Jewish tradition: to remember is the secret of redemption. And that of George Santayana, so often quoted in relation to Nazism: those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it. On the other hand, there is the profound insight of the historian Ernest Renan that every nation is a community both of shared memory and of shared forgetting. (200)

He recognises the accident of birth:

I was just so lucky. Lucky in the country of my birth. Lucky in my privileged background, my parents, my education. Lucky in true friends like James and Werner. Lucky in my Juliet. Lucky in my choice of profession. Lucky, too, in my cause. For the Central European struggle against communism was a good cause. Born a few years earlier, and I might have been backing the Khmer Rouge against the Americans. Born in a poor family in Bad Kleinen, East Germany, and I might have been Lieutenant Wendt. […]

What you find here is less malice than human weakness, a vast anthology of human weakness. And when you talk to those involved, what you find is less deliberate dishonesty than our almost infinite capacity for self-deception.

If only I had met, on this search, a single clearly evil person. But they were all just weak, shaped by circumstance, self-deceiving; human, all too human. Yet the sum of all their actions was a great evil. It’s true what people often say: we, who have never faced these choices, can never know how we would have acted in their position, or would act in another dictatorship. So who are we to condemn? But equally: who are we to forgive? “Do not forgive,” writes the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert,

Do not forgive, for truly it is not in your power to forgive

In the name of those who were betrayed at dawn.

These Stasi officers and informers had victims. Only their victims have the right to forgive. (223–4)

He notes people’s withdrawal into private lives:

Intelligent, well-educated, well-informed through watching Western television, they nonetheless devoted virtually all their energies to their private lives, and particularly to extending, decorating and maintaining their cottage on a small lake some half-an-hour’s drive from Berlin. […] My friend Andrea too, concentrated on private life, bringing up her small children in the charmed atmosphere of a run-down old villa on the very outskirts of Berlin. There were lazy afternoons in the garden, bicycle-rides, sailing and swimming in the lakes. (66)

The intersection of family and political history is well described in

- Thomas Harding, The house by the lake,

a microcosm of modern Germany. I’m also most impressed by

- Maxim Leo, Red Love (to which I devote a separate post)

—not least by the author’s amazing counter-cultural parents: compared to the lives of my own parents, theirs have been anything but drab. And then there’s

- Hester Vaizey, Born in the GDR: living in the shadow of the Wall

To return to The file, Garton Ash observes the insidious use of language:

The process for which English has no word but German has two long ones: Geschichtsaufarbeitung and Vergangenheitsbewältigung. “Treating”, “working through”, “coming to terms with”, or even “overcoming” the past. The second round of German past-beating, refined through the experience of the first round, after Hitler. (194)

Another distinctive mouthful with echoes of China is Parteiüberprüfungsgesprach, “a ‘scrutinizing conversation’, a kind of confession for loyal comrades” (Red Love, p.212).

And after my citation of an over-generous definition of the Chinese term dundian, in German not just words but definitions can be expansive too. Abschöpfung is

laboriously defined in the 1985 Stasi dictionary as “systematic conduct of conversations for the targeted exploitation of the knowledge, information and possibilities of other persons for gaining information”. The nearest English equivalent, I suppose, is “pumping”. (108)

Garton Ash goes on to ponder the surveillance system of his own country:

The domestic spies in a free country live in this professional paradox: they infringe our liberties in order to protect them. But we have another paradox: we support the system by questioning it. That’s where I stand. (220)

And

Thirty years ago, when I went to live in East Germany, I was sure that I was travelling from a free country to an unfree one. I wanted my East German friends to enjoy more of what we had. Now they do. In fact, East Germans today have their individual privacy better protected by the state than we do in Britain. Precisely because German lawmakers and judges know what it was like to live in a Stasi state, and before that in a Nazi one, they have guarded these things more jealously than we, the British, who have taken them for granted. You value health most when you have been sick.

I say again: of course Britain is not a Stasi state. We have democratically elected representatives, independent judges and a free press, through whom and with whom these excesses can be rolled back. But if the Stasi now serves as a warning ghost, scaring us into action, it will have done some good after all. (232)

German fictional treatments of the period include

- Christa Wolf, They divided the sky, and

- Eugen Ruge, In times of fading light.

And then there are films like Barbara (2012)

and The lives of others, perceptively reviewed by Garton Ash.

Going back a little further, among innumerable portraits of ordinary German lives compromised, warped, under Nazism, I admire

- Hans Fallada, Alone in Berlin.

Here’s a playlist of 65 English-language documentaries on the GDR:

not apparently including the 1970 BBC film Beyond the Wall, which you can still watch here. For subversive feature films made under the regime, see here; and for a documentary on WAM, here.

* * *

The nuance and detail of studies like those of Garton Ash contrast with Dikötter’s blunt and pitiless agenda in exposing the undeniable iniquities of the Maoist system.

While China and Germany were utterly different, parallels are explored by

- Stephan Feuchtwang, After the event: the transmission of grievous loss in Germany, China and Taiwan,

and by Ian Johnson.

But for China, archives, and even memory, remain hard to access. For the Maoist era, the literature on the famine is growing—note especially Wu Wenguang’s memory project. Among fictional treatments, few films are as verismo as The blue kite and To live, or (for the last throes of Maoism) the films of Jia Zhangke. Chinese novels too tend towards either magical realism or over-dramatising.

For crime fiction from China and Germany, see here; for life-stories in the Soviet Union under Stalin, click here.

Along with regions like

Along with regions like

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/A-843647-1270908146.jpeg.jpg)

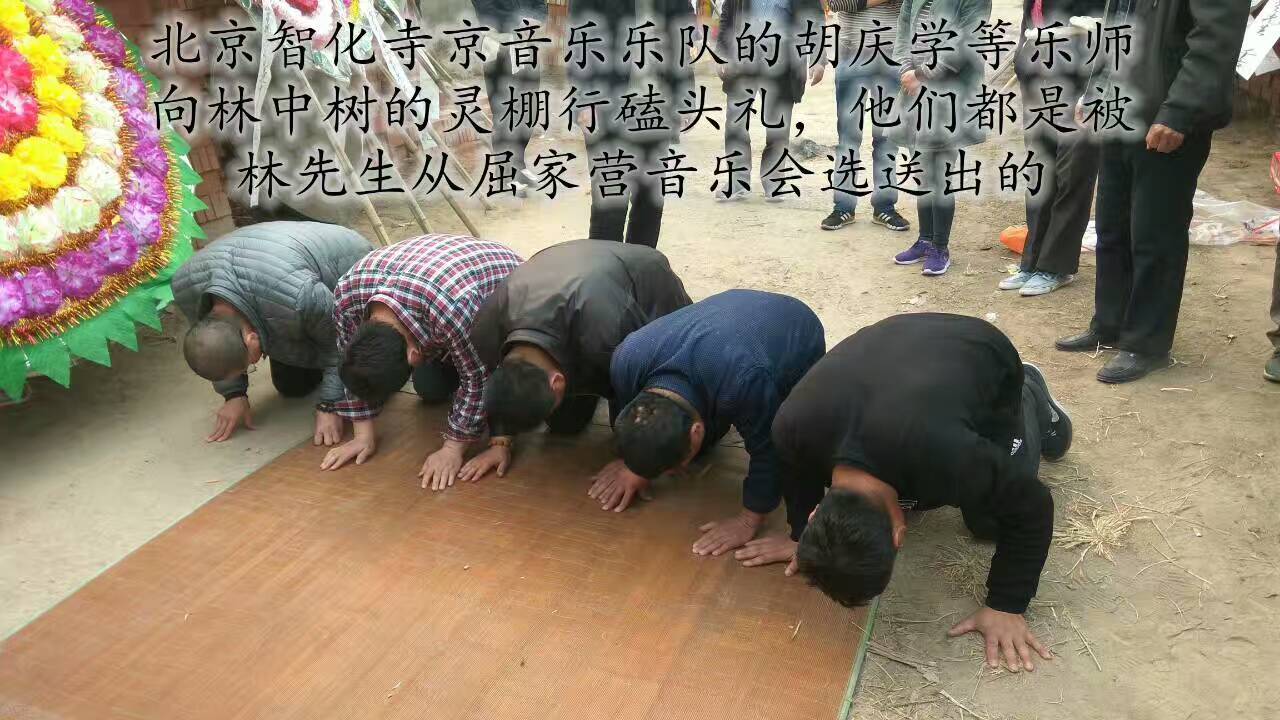

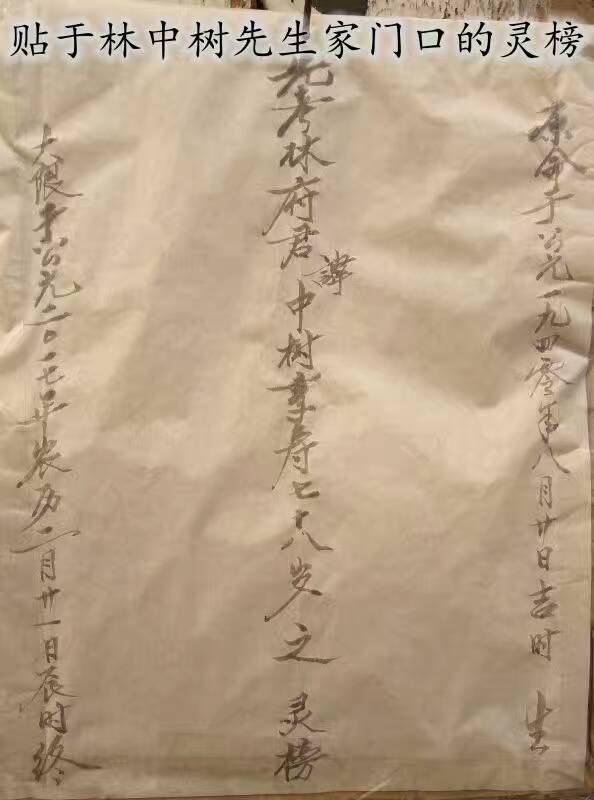

Led by Hu Qingxue, Qujiaying villagers, later trained in the Zhihua temple style, kowtowing before the soul hall at Lin Zhongshu’s funeral, and playing the classic sequence Jinzi jing, Wusheng fo, and Gandongshan.

Led by Hu Qingxue, Qujiaying villagers, later trained in the Zhihua temple style, kowtowing before the soul hall at Lin Zhongshu’s funeral, and playing the classic sequence Jinzi jing, Wusheng fo, and Gandongshan.

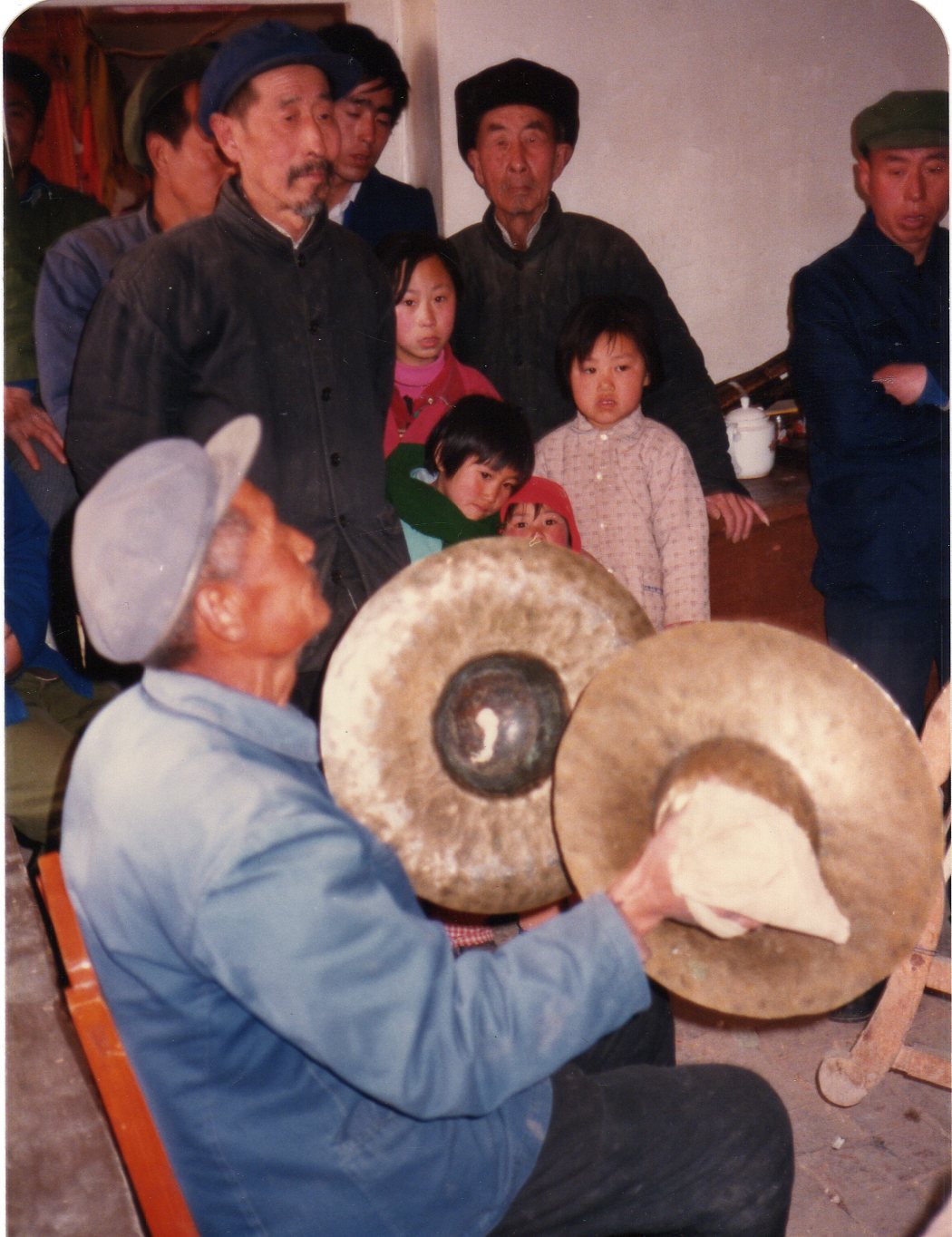

Shawm players from Mizhi county, assembled for a regional festival in 1981.

Shawm players from Mizhi county, assembled for a regional festival in 1981.

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997.

Temple procession, Xincheng, south Gansu, June 1997.