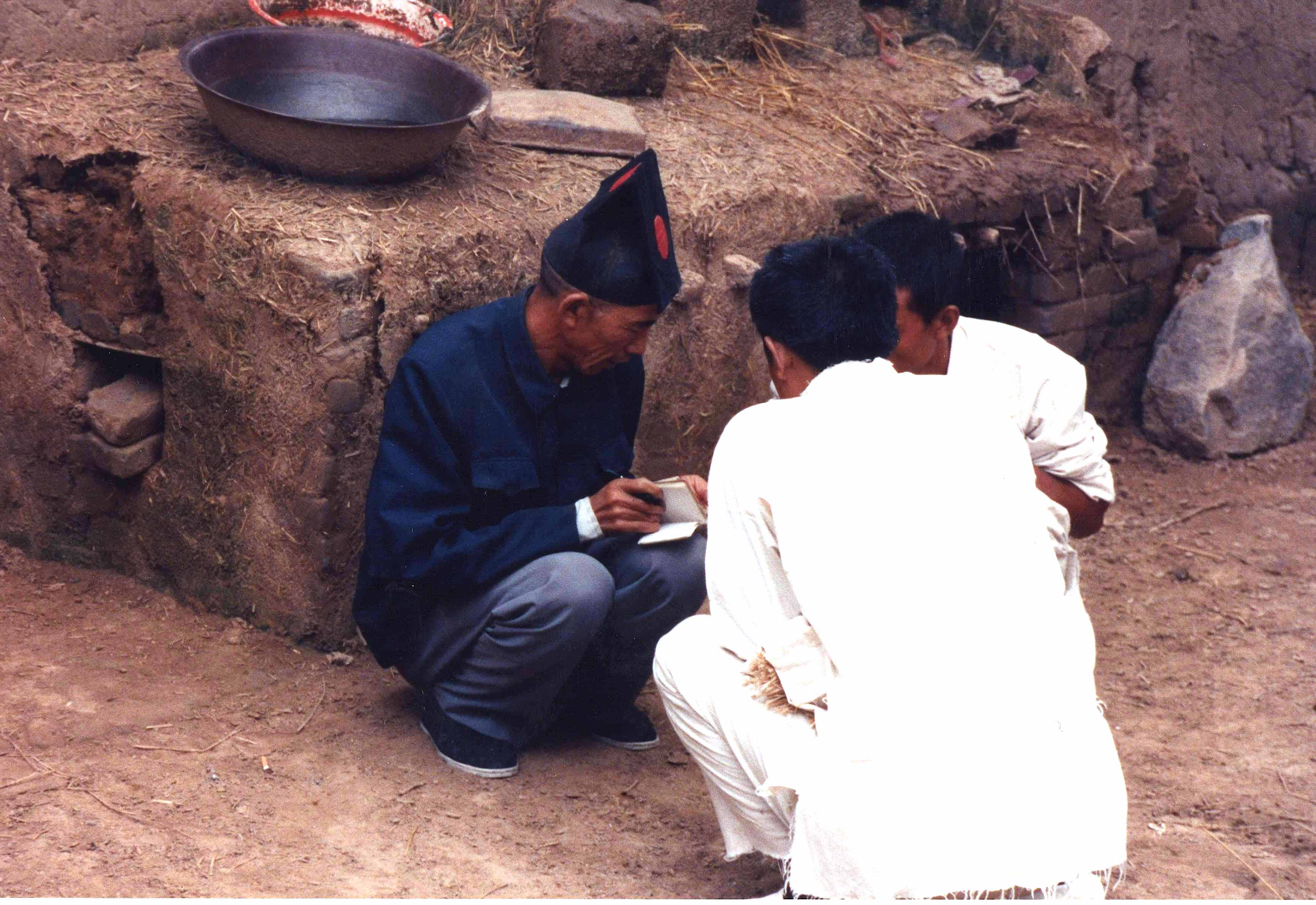

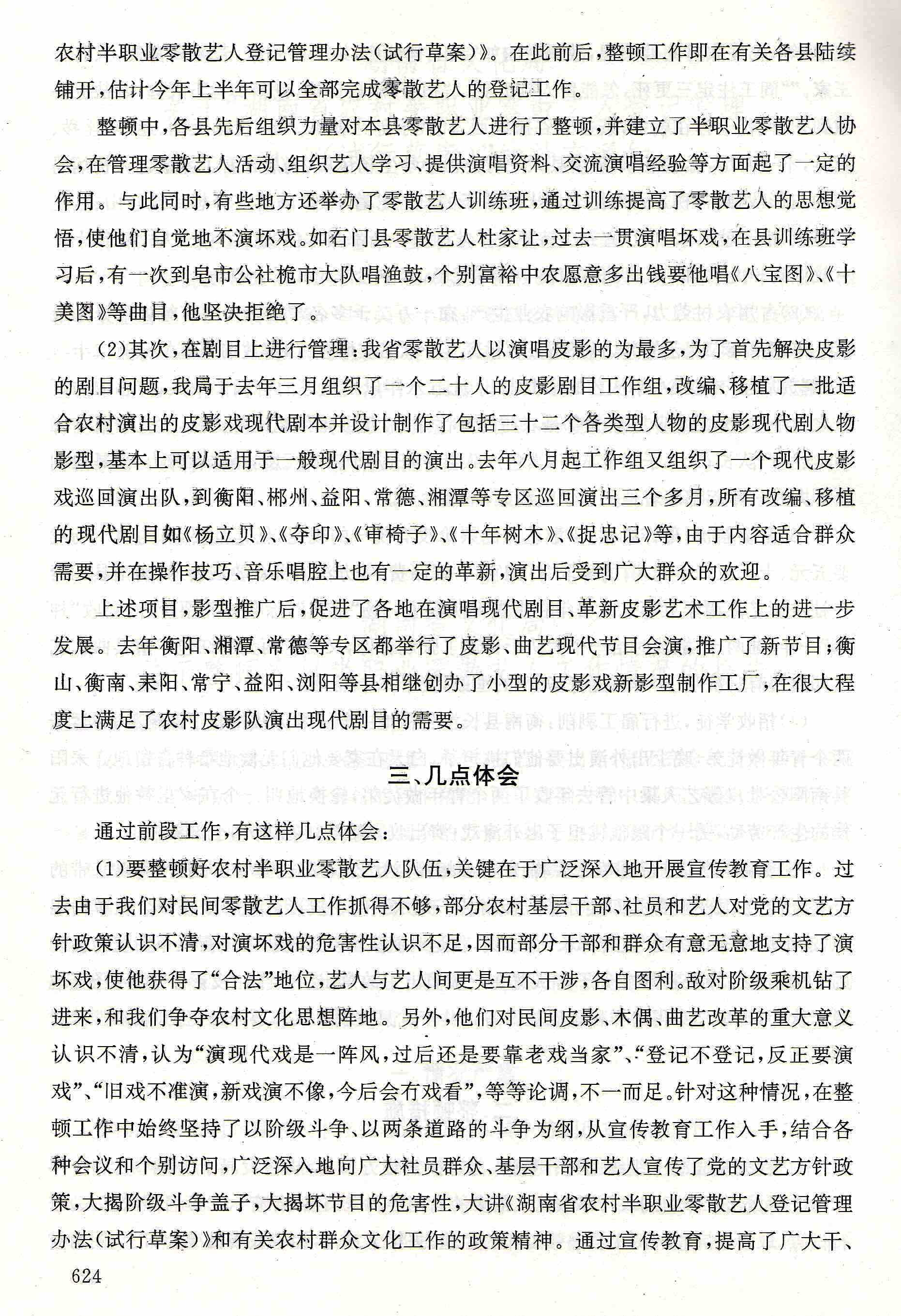

2005: Guo Yuhua chats with the last man in Jicun village still wearing the traditional headscarf of the north Chinese peasant, iconic image of the revolution. Photo courtesy Guo Yuhua.

During my recent sojourn in Beijing, as well as my lecture series at Beishida and film screenings at People’s University and Peking University, it was a great inspiration to meet up again with the fine anthropologist Guo Yuhua 郭于华 (b.1956).

She’s done an interview for Ian Johnson (latest in a fine series for the NYRB); this interview is also instructive, as well as this earlier one in Chinese, along with recent posts by David Ownby (here, here) and Jonathan Chatwin, so here I’d just like to add my own personal reflections on her extensive oeuvre, with further material on fieldwork. [1]

1 Introduction

Introduced in London by the great Stephan Feuchtwang in the 1990s, we later met up in Beijing. In 1999 she took me on a fieldtrip to the Shaanbei village that was already a major focus of her research. In March 2018, not having seen her for ages, I was keen to catch up.

Professor of sociology at Tsinghua university in Beijing since 2000, Guo Yuhua is widely admired by scholars in China and abroad, maintaining high academic repute in the innovative sociology department alongside Shen Yuan 沈原 and Sun Liping 孙立平. [2] What distinguishes them from other China anthropologists—both in China and abroad—is their rigorous critique of “Communist civilisation”.

I meet Guo Yuhua on the vast Tsinghua campus one afternoon and we go to a quiet café. I sip a bucket-sized strawberry frappé for hours as she delivers a passionate tirade/lecture, talking non-stop.

After gaining her PhD at Beishida and doing a post-doc at Harvard, by the 1990s Guo Yuhua was involved in a major project on oral history at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), documenting villagers’ personal experiences of the Maoist era—a project very far from the traditional oral history of folklorists.

Her early fieldwork focused on folk culture (as was the vogue at the time), but as she began delving deeper she moved onto the wider, and deeper, social and political systems of modern life. In 1999 she edited the influential book

- Yishi yu shehui bianqian 仪式与社会变迁 [Ritual and social change] (Beijing: Shehuikexue wenxian cbs),

with contributions from leading scholars like Wang Mingming and Luo Hongguang. Most articles explore the complex relation between local society and the state. Apart from her introduction, her own article there expounds many of the issues in her 2013 book (see below):

- “Minjian shehui yu yishi guojia: yizhong quanli shijiande jieshi” 民间社会于仪式国家:一种权利实践的解释 (陕北骥村的仪式于社会变迁研究) [Folk society and the ritual state: an interpretation of the practice of power (Ritual and social change in Jicun, Shaanbei)].

Guo Yuhua was an early blogger, later moving onto Weibo, Wechat and Twitter, where she is indefatigable in exposing injustice and defending rights.

Surveying her activist online activity, it might seem as if she’s changed paths since her early fieldwork on rural society and ritual, towards a deeper political engagement. But far from it, it’s all a continuum (“the whole dragon” again)—the social concern was always there. Amidst the current threat to our own values in the USA and Europe, many Western scholars may now be appreciating her wisdom.

But in China, such a principled stance requires more determination. Guo Yuhua’s blog and social media accounts have long been regularly blocked or censored. As she observes, in the face of constant scrutiny, it’s never clear where the line is—you just have to keep probing. The Party can’t control thought totally—the genie is out of the bottle, and China has to stay open for business; social media stills brings information and can be astutely deployed. Still, plain speaking is easier for established scholars than for younger scholars starting out.

I’m scribbling notes as she talks, but after a while my pen runs out. I suggest, “Is this one of Theirs, trying to stop me writing down your Thoughts?!”

Apart from her Tsinghua colleagues, scholars she admires include historians Qin Hui 秦晖 and Zhang Ming 张鸣; and in legal studies, Xu Zhangrun 许章润 (for the latest in a series of critiques, see here; and for Guo’s defence after his 2019 suspension, here), He Weifang 贺卫方, and Zhang Qianfan 张千帆 (individual articles also on aisixiang.com—gosh, what an important resource this site is!). Guo Yuhua is part of a chorus of scholars criticising the “New Rural Construction” campaign, with its coercive programmes of expulsion.

Complementing her through background in Western sociology, her work builds on Chinese tradition—like Fei Xiaotong’s candid account of villages evading state collective policy (Dikötter, The Cultural Revolution, p.280).

Though she is closely surveilled even when she does rural fieldwork, she never loses her sense of humour—she has lots of funny stories about her fieldwork, and being surveilled. She seems cool and open, knowing she’s doing the moral thing, saying what needs to be said, on the basis of her rich practical and theoretical experience, with careful detailed scholarly research. She speaks for truth, that of the common people among whom the CCP once gained support by espousing. She does all this not out of “bravery” but more as a duty, like the patriotic intellectuals of yore. As she comments in the NYRB interview,

Sometimes, you feel you can’t tolerate it—you have to speak out. And if you’re looking at the people in society who are suffering, well, they’re so pitiful. It’s intolerable. You feel you can’t help them in another way, so at least you can try to publicise it and get a public reaction. In fact, you aren’t really helping them, but you feel you have to speak.

And she still manages to take teaching very seriously. Her courses, with impressive reading lists, include rural sociology, research methods, and the sociology of politics. Taking students on village fieldwork, she even does livestreams.

Such Chinese scholarship doesn’t tally neatly with Western concepts of left and right. Over here, last time I looked, those who strive for social justice and speak truth to entrenched conservative power are considered on the left. But When Guo Yuhua visited the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle in 2016, making a critique of Karl Polanyi’s views on the market economy, their views were at odds.

While she understands my lament that some foreign media coverage seems to suggest that Chinese people are brainwashed automatons, she still worries that many are indoctrinated. Like in the USA, I ask? I may sometimes feel uncomfortable with foreign China-watchers’ monolithic portrayal of an evil surveillance state, but Guo Yuhua, in the thick of it, commands great authority.

* * *

Fieldwork may stimulate a social conscience (cf. journalistic reports like those of Liao Yiwu), and anthropology has a long history of activism—if less so for China. The task is to understand different lives, and speak out on people’s behalf—obvious topical instances including Syrian refugees and Beijing migrants.

I’m tempted to wonder, isn’t this a natural career path for any anthropologist (or indeed priest) working among the poor? What may seem more curious is that many, whether Chinese or foreign, don’t follow such a path. Exposure to the lives, and cultures, of rural dwellers should inevitably prompt us to ponder their situation—but that rarely surfaces clearly in the literature on China. And it does seem to lead naturally to a principled involvement with issues of social justice. So perhaps that’s why authoritarian governments are likely to be wary of anthropology, and “experts” in general.

The anthropology of ritual and expressive culture in China may seem somewhat separate from such social and political enquiry, but it needs to absorb such lessons (as I often suggest. e.g, here). So with much research on Chinese music and Daoist studies still blinkered and stuck in reification and myths of an earlier idealised past, I’ve long looked to anthropology for inspiration. Still, compared to the 1990s when one could do meaningful work, Guo Yuhua finds the current anthropological scene in China backward, with funding ever more politically controlled.

Of course, anthropologists don’t only study exotic tribes and peasants. They may also explore the lives of the legions of those who make “our” own pampered lifestyles possible—migrants, cleaners, construction workers, often from poor villages whose conditions the anthropologists may also document.

Under Maoism the Chinese Masses were thoroughly exploited even while they received empty praise as salt-of-the-earth laobaixing, but since the 1980s’ reforms state media have serially demonised them with the taints of “low quality” (suzhi di) and “low-end population” (diduan renkou). Guo Yuhua is always on their side.

2 Narratives of the sufferers

There’s already a substantial literature in Chinese and foreign languages not only on Shaanbei-ology (see also Shaanbei tag) but on the village of Yangjiagou (Guo Yuhua uses its old name, Jicun). It features prominently in my own book

Adapted from pp.xxvi–xxvii there:

In the hills east of Mizhi county-town, Yangjiagou has been the object of study for a steady stream of Chinese and foreign scholars. It is not necessarily typical, in that it was home to a dominant local landlord clan in the Republican period, and has been visited by sociologists since the 1930s; since Chairman Mao stayed there in 1947 it has become a minor revolutionary pilgrimage site. Sociologists with new agendas have made thorough restudies since the 1990s, and recently a Japanese team has published a book on its architecture, soundscape, and society. Today villagers have become all too accustomed to outsiders. However, the revolutionary connection hasn’t protected it from poverty. Though only 18 kilometres from the main road, it was a difficult journey until 1999. The village gained electricity only in the early 1980s, and its first telephone only in 2000. Though Yangjiagou’s musical traditions have been declining since the 1930s, they were maintained into the reform era. My modest contribution to Yangjiagou studies is to attempt to put the lives of its bards and its shawm-band musicians since the 1930s in the wider Shaanbei context.

By the time Guo Yuhua took me on my first fieldtrip to Shaanbei in 1999 she was already engaged in an important oral history project there. I suppose my tagging along with her confirmed my gradual shift towards the more social approach that had already been emerging in my work with Chinese colleagues in Hebei—an approach more embedded in the changing lives of people than was, or is, the fashion in either musicology or Daoist studies.

It was a great trip, instructive and fun—even if she was doubtless underwhelmed by my limited ability to behave suitably with either peasants or cadres. But I learned a lot from her, from the warmth and honesty of her rapport with villagers, right down to little practical details like buying a modest amount of incense paper as a suitable gift on attending funerals.

We spent some time around the Black Dragon Temple—another site which she and Luo Hongguang were studying, later covered in Adam Chau‘s book Miraculous response—before going to stay in Yangjiagou.

Guo Yuhua’s principled stance is shown in a nice story from our fieldwork together. In my Shaanbei book (p.147) I describe how I found some obscure tapes of shawm bands there:

I sweated blood to get hold of some of these cassettes. Few shops stock more than a couple of them, and I finally tracked down a selection on an expedition by foot to a dingy general store in the sleepy township near Yangjiagou. As I eyed the cassettes up over the counter, the dour assistant—who apparently hadn’t ever sold any of them, and certainly not to a foreigner—spotted a business opportunity. She ingenuously asked 5 yuan each for them—I had enough experience to realize they sold at around 2 yuan. My companion Guo Yuhua was indignant, and we launched into some increasingly impolite haggling. But the assistant wouldn’t budge. I generally get angry when people try to overcharge me in China, but having been searching for these tapes for years, in this case I was inclined to allow myself to be ripped off—the three tapes I had set my heart on would still cost less than a half-pint of London beer. But for Guo Yuhua the principle was clear, and she dragged me out of the shop, refusing to let me part with my money.

After some spirited exchanges as we set off back to Yangjiagou along the filthy main track, debating the balance between adhering to principle and yielding to corruption, I dashed back to the shop and bought them at the inflated price, flinging the money at the assistant with a vain display of sarcasm that went clear over her head.

Guo Yuhua reminds me how my visits to the latrine always prompted the “patriotic” family dog, chained worryingly nearby, to bark fiercely—but a visit from a district cadre also aroused its ire, so it had a certain taste. Another vignette:

One day in 1999 we visit a former village cadre—who also happens to be a spirit medium—to chat with him while his wife prepares lunch for us (“Typical!“), when in walks a young policeman from the township nearby, in search of a signature from our host for some bureaucratic trifle. I’m a bit alarmed, not so much as we’re kinda talking about some sensitive stuff here, but because as the climate relaxed through the 1990s we had reckoned we could probably economize on the laborious rounds of local permits that my forays once invited. Sure enough, the cop eyes me somewhat ferociously and goes, “What’s this wog [oh yes, there’s another story!] doing here?”

When our host explains that I’m from England, even before I can launch into some spiel about collecting the fine local folk music heritage, blah-blah, international cultural exchange, blah blah, he is open-mouthed. “Do you like Manchester United?” he asks, spellbound. Relieved, I launch into my Beckham routine, we exchange cigarettes as we discuss the prospects for the World Cup, and he leaves contented.

On my second stay there in 2001, this time accompanied by Zhang Zhentao, I spent more time with the village’s lowly shawm players (see below), and appreciated them a lot.

An important book

Propaganda is pervasive—and not just in China, as this recent attempt at debating the British legacy shows. The romantic patriotic image of Shaanbei (cf. my post One belt, one road), deriving first from Mao’s base there on the eve of “Liberation”, is now further entrenched by the bland legends of Xi Jinping’s seven years there as a “sent-down youth” during the Cultural Revolution.

Guo Yuhua’s article on Jicun in Ritual and social change already broached many of the issues expounded in her 2013 book

- Shoukurende jiangshu: Jicun lishi yu yizhong wenming de luoji [Narratives of the sufferers: The history of Jicun and the logic of civilization] (Hong Kong: Chinese University, 2013)

(for Chinese reviews, see e.g. this by Sun Peidong, herself hounded out of her post at Fudan in 2020).

If I were King of China (an unlikely scenario), it would be required reading for all. But I’m not, it’s not, and even to find a copy in the PRC may take a certain ingenuity.

As Guo Yuhua writes [Harriet Evans’s translation],

We discovered that ordinary peasants are both able and willing to narrate their own history, as long as the researcher is a sincere, respectful, serious and understanding listener.

Notwithstanding my comment that ethnography is about description, not prescription,

Bourdieu and his collaborators’ work in listening to these people’s stories and entering their lives can be seen as a fulfillment of the sociologist’s political and moral mission—to reveal the deep roots of the social suffering of ordinary people.

The peasants of Ji village where we have been carrying out fieldwork for many years refer to themselves as “sufferers”. This is not a term that we as researchers have imposed on the subjects of our research; rather it is the definition that villagers give to themselves. In the region surrounding Ji village, “sufferer” is a traditional term that peasants continue to use today to refer to those who farm the land present. In local language, the “sufferers” are those who “make a living” on the land; it is a local term that is popularly accepted and conveys no sense of discrimination. When you ask a local person what he is doing the common response is “zaijia shouku” (lit. “suffering at home”), in other words, making a living farming the land.

[from Harriet Evans’s translation].

In the Hong Kong interview Guo Yuhua explains,

Of course, in doing oral history we would never expect people to “tell about your suffering”—we’d never ask like that. Rather, we ask them to tell us their stories: how their life was when they were young, when they grew up, married and became parents. We don’t go in search of suffering, and their accounts aren’t entirely about pain. Sometimes their stories sound really painful, but they will talk very ironically. Often we find women laughing and crying at the same time—one moment crying as they talk of heartache, the next finding it funny how foolish they must have been at the time.

[…]

Scholars aren’t some Arts Propaganda Troupe [!!!]—we don’t have to extol how happy and contented we are nowadays, that’s not our job [cf. “WTF” article in n.1 below]. Our job is to view the issues in this society, to understand the painful experiences of ordinary people, and where they come from.

Citing Xu Ben 徐贲 (For what do human beings remember? 人以什么理由来记忆) and Wu Wenguang’s project on the famine, she goes on to discuss the significance of memory.

Apart from the villagers’ own accounts, the subtlety and perception of Guo Yuhua’s enquiries are a model for fieldworkers (e.g. 211–12).

As we will always find, the village’s history is utterly remote from its model revolutionary image. You might think it would take more effort to ignore what happens than to document it, but people have been effectively groomed in public amnesia. The case of Yangjiagou is all the more revealing since it is a common rosy theme online, including videos, based on the image of Mao’s sojourn there and the whole CCP myth-making. It also makes a good case because there were no excess deaths there in the “famine”; unlike the labour camp stories, it’s a story not so much of extreme degradation but rather the routine degradation of daily life—the constant hunger, duplicity, and brutality.

Breaking free of the simplistic class narrative of Maoism, Guo Yuhua’s thorough theoretical Introduction [3] is inspired notably by Bourdieu, as well as authors like James Scott, Philip Huang, and Guha and Spivak; for the stories of women, she cites Marjorie Shostak.

Clearly written and structured, the book highlights the vivid voices of the local “sufferers” (including former “landlords”, cadres, women, and so on), linked by her trenchant commentaries.

Chat with village women, 2006.

The memories of women form a major component of the story, on which she reflects thoughtfully—not least issues in eliciting their more domestic world-view (e.g. 127–37; cf. this article).

Women do recognize the social “conviviality” (honghuo) of being forced out of the house to work in the collective fields. [4] But the true impact of hunger hits home in their accounts of childcare, with the constant anguish of being unable to feed their children.

In the Hong Kong interview she expands on the changing status of women, as ever disputing the Party line:

Some scholars consider that after rural women had experienced the female liberation (elevating their status), they regressed after the reforms. But after you have done fieldwork among rural women and listened to them describing their life experiences, you will realize that it simply couldn’t be called “liberation”. However is liberation passive? To be called liberation it has to be autonomous, personal. Their status was merely changed: previously dependent on family and lineage, they were now dependent on the state and the collective. They remained tools, objects, being organized and mobilized into collective labour against their will. What they seem to be telling is how they fell sick, exhausted by labouring, looking after children, sewing, enduring famine amidst a lack of material goods. Such accounts may sound like trivial matters, but the whole background it is quite clear what it really meant to be a rural woman, and what it was that created their plight. With no room for choice, women had to do what they were told; they had to take on the most exhausting, physically demanding tasks, not even able to recuperate properly after giving birth, thus subjecting them to disease. Their condition was one of enslavement.

After the reforms, they could leave the village to work, and there were plenty of active young women able to use their determination and aptitude to change their fate to some extent. This was definitely progress, but it wasn’t an automatic process: there were still many constraints, with injustices at many institutional levels. Still, although many girls don’t appear independent, and may choose to find a good husband, at least they have this choice; or they can choose to go and study, become female enterpreneurs and independent women. All this gives them more choices than under the collective era.

Adroitly adopting the recent CCP buzzword hexie 和谐, Guo Yuhua pointedly details how—both under Maoism and since the reforms (121, 240–41)—the “harmonious” social relations of the old society were polarized and moral values poisoned.

The revolution brought to the fore the less reputable elements in local society, like the local bully who used his new power as an activist under the CCP to torture a “landlord” into giving him his young daughter in marriage (60–61). And the villagers remained disgusted despite his political power. As she notes, facing such problems in mobilizing the masses, “the use of bad people became the only choice” (112–14).

As throughout Shaanbei, infant mortality rates were high, both before Liberation and under Maoism. Apologists like Mobo Gao point out certain advances (in healthcare, education, and so on) under the commune system; the Mizhi county gazetteer (p.630) [5] claims an increase in life expectancy from 35 in 1949 to 60 by 1989. Indeed, the villagers concede that some of the economic advances since the reform era were based on the desperate projects under Maoism.

But for Guo Yuhua such defences are derisory. On my interminable bus journey back to Beijing in 2001 I chatted with a modest young guy from poor Jiaxian county who was studying for an economics PhD at People’s University in Beijing; he was one of fifteen children, of whom only three had survived.

In numerous villages like this where there was no resentment towards the landlords (they were widely considered “benevolent”), and the concept of “exploitation” was alien, the CCP had to manufacture “class hatred” by the indocrination of constant campaigns. Landlords and their children, educated and able, joined both sides of the conflict, working away from the village until they were dragged back to be punished as “sacrificial victims”, notably with the layoffs from state work-units around 1962 (another universal theme in my own studies, e.g. Li Qing in Yanggao: Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.113–18).

She concludes: “Overall, before 1946 Jicun was a relatively tranquil and serene traditional village.” (Discuss…)

The new rulers now had to foster class consciousness. With both oral accounts and substantial official sources Guo Yuhua documents the stages of land reform, with its inevitable corruption and theft. [6] Conscription, brutally enforced (108–10), added to their woes. Citing Zhang Ming (see above), she shows how the goal of land reform was not economic but political (113).

She refutes the CCP myths of “temporary problems” like the Cultural Revolution, or the “three years of difficulty”: just as I found in north Shanxi, villagers were starving for over two decades, from collectivization right until privatization.

After a brief interlude when the peasants at least nominally had their own land, a long succession of political rituals now cowed the villagers into obedience, condemning them to long-term hunger, exhaustion, and sickness. Having already suffered famine in winter 1947–8, their hunger became ever more severe as collectivization was enforced; one villager recalls that from 1958 to 1979 it got worse year by year (154). Scavenging was the only hope of survival. We may note certain parallels in the fate of a First Nation community in Canada.

Coercion was an intrinsic component of the whole system, and excessive violence was rewarded (236–8). As the objects of attack soon expanded from the landlord class to the whole rural population (114), campaigns became a life-or-death struggle.

In describing the stages of collectivization, Guo Yuhua reminds us of the traditional voluntary methods of mutual help, and the whole ethical system, that were demolished (117–21).

Stressing the militarization of society, she details the whole succession of what the villagers call “a fucked-up flim-flam” (luanqibazaode mingtang 乱七八糟的名堂)—like short-lived care enterprises for children and the childless elderly, largely unsuccessful literacy campaigns, the failure to teach revolutionary songs. After the sheer desperation following the Great Leap and the short-lived communal canteens, the interlude when private plots were tolerated from 1961, giving peasants a slender lifeline, was all too brief before the Socialist Education and Four Cleanups campaigns led into the Cultural Revolution, as hunger became endemic again. Cadres were just as clueless as ordinary villagers about the details and goals of these “rotten” campaigns; and the aims of factional fighting (180–82) were no clearer, apart from the constant cycle of petty revenge that the whole system had long fostered.

Apart from the persecution of cadres, the landlords again made inevitable scapegoats. Only two villagers met violent deaths in the Cultural Revolution (and that after the main violence of 1966–8)—but their story still haunts villagers today (182–6).

With its landlord history, the village had a wealth of fine old architecture. Nearly forty years after a stone mason was recruited to detonate “the finest archway in Shaanbei”, Guo Yuhua finds him to tell the story.

The former landlord stronghold, 1999.

As in Europe, even today the older buildings that somehow survived look picturesque—as long as you don’t dwell too much on the indignities that they have witnessed.

Village centre, 1999.

Cave-house of our host family, 2001.

By the 1960s villagers’ disillusion was complete. Still, Guo Yuhua notes their own later conflicted memories (cf. the Soviet nostalgia for Stalinism):

- the sense of conviviality (honghuo) enforced by collective labour (including singing haozi work hollers), which she compares with the “collective effervescence” of ritual;

- the sense that they were all in the same boat—scant consolation when people were all destitute and starving together, but contrasting with their later atomization since the reforms:

Out we went, voices all round, chattering away merrily, convivial all of a sudden. As soon as we got back home, there was nothing to eat, the kids were crying, clothes all tattered, nothing to mend them with—just that moment of conviviality.

[…]

Commenting on their more recent memories, she notes

Material amelioration and the deterioration of social life, as well as nostalgia for the collective life produced by their escalating marginalization, to some extent transforms and even conflicts with their memories of suffering.

- and their startling ironic “logic” that with the collapse of the commune system the CCP slogan “first bitter, then sweet” (coined to contrast the old feudal society with the Communist Utopia) had indeed finally come to pass with the present material sufficiency—albeit several decades too late, and only after the collapse of the very system that had touted the boast (156–65). For some, the transition

from collective to privatization wasn’t a retrogressive transformation of correcting the mistakes of the system, but like a natural “first bitter, then sweet” cause-and-effect.

She notes the villagers’ sullen passive resistance in showing up for collective labour without working, citing the dictum of Qin Hui (see above) that communes from which people can’t withdraw are no different from concentration camps.

Since the reforms

As the stultifying commune system collapsed (“rotted” as they say, lan nongyeshe 烂农业社; another common expression for the privatizing reforms is dan’gan 单干, “going it alone”), the book describes the long complex process of adjustment.

With villagers clamouring to overthrow the commune system, at first some cadres hesitated to stick their necks out, anxious that the political winds might change yet again.

A vivid exchange in an interview with a former cadre:

Later it became the norm, the whole county was dividing up…

[Woman interjects:] It was spring. I remember dividing up the donkeys, don’t I.

Cattle, you mean cattle.

[They argue over whether it was donkeys or cattle…]

As for villagers in north Shanxi, this was the real “Liberation”:

Going it alone was great, just great. If we’d have gone on in the collective, in a few more years there’d be no-one alive, we’d all have fucking starved to death [laughs]—really! (212)

Guo Yuhua goes on to reflect on the mechanism that had enabled such coercion, and the villagers’ own assessment of the changing times, including their reservations about the way society had gone on to evolve (213–21).

In the final chapter she draws conclusions, exploring the “logic” of both sufferers and the system that they endured, and warning that the campaign style is still active.

In an Appendix (also online) entitled “Doves occupying the magpie’s nest” she updates the story, reflecting on later visits in 2005 and 2006. The dwelling where Mao stayed from 1947–8 had been revamped as “Commemorative hall to the revolution”, and the former ancestral hall of the Ma landlords was being converted to an “Commemorative hall to the battle relocation in Shaanbei”, an “educational base on the revolution”. No room for the villagers’ own voices here.

Taking a tour of Mao’s old dwelling she suddenly realizes that two of the cave-dwellings—former residence of Peng Dehuai, no less—had become the home of the eccentric villager Liudan, whose father had made such a deep impression on Guo Yuhua that she had published an article about him in 1998:

Though from a landlord background, he was considered “enlightened gentry”, and was on the advisory team for land reform. Becoming a teacher away from the village, he was yet another victim of the state cuts in 1962, having to return home. He now became “maladjusted”, cut off from village life.

Now, amazingly, his son Liudan was still occupying the two caves in the revolutionary site, adamantly refusing the state’s handsome offer of money to move out. Never able to find a wife, he too was unable to work; most villagers understood his seeming mental deficiency as a highly astute form of passive resistance. Even recently he was still something of a down-and-out. As Guo Yuhua observes, his refusal to move out was reminiscent of both the indignant protests of evicted urban dwellers and the struggle over whose version of history will prevail; but given his mental frailty, his resistance was rather complex.

Anyway, we needn’t hold our breaths for a memorial to the victims of Maoism, to match the commemoration sites in Germany for those of Nazism and the GDR.

And Guo Yuhua still manages to go back regularly to Yangjiagou—even as year by year, fewer people remain who can recall the period before “Liberation”; before long, who will remember the Great Leap Backward?

Village chat. 2011.

As in Europe, we all visit sites where people were tortured and murdered within living memory, yet we may merely see them as picturesque—an image avidly promoted by Chinese propaganda.

* * *

Language

One feature that enriches the authenticity of the book is its direct citations of villagers’ accounts in their own words. Thus it also serves as a kind of practical handbook for Shaanbei dialect. Use of language, of course, lends insights into people’s conceptual world. [7]

Apart from having to latch on to regional pronunciations, like de (duo), hou (hao), he (hei), bie (bei), ha (xia), ka (qu), and so on, Guo Yuhua soon helped me pick up some basic expressions, like haikai 解开 “understand” and chuanka 串去 “go for a stroll”. Now I can finally savour the language of her meticulous documenting of peasants’ reflections, albeit twenty years too late—basic expressions like nazhen 那阵 “then” (jiuqian 旧前 “in the old days”); zhezhen 这阵 or erke 尔刻 “now”; laoha 老下 “dead”; yiman 一漫 “totally”; ele 恶了 “very” (not the standard feichang). The whole commune system is known as nongyeshe 农业社 or daheying 大合营; for collective labour they say dongdan 动弹.

Among the many pleasures of peasant language is its liberal use of expletives, a revealing contrast with the standard Chinese of propaganda—polished, polite, and so flagrantly false as to insult the intelligence.

Religion and ritual

Guo Yuhua’s PhD, which became the book

- Side kunrao yu shengde zhizhuo 生的困扰与死的执着:中国民间丧葬仪式与传统生死观 [The puzzle of death and the obstinacy of life: Chinese folk mortuary ritual and traditional concepts of life and death] (Beijing: Zhongguo Renmin daxue cbs, 1992),

largely concerned traditional rural mortuary rituals, and remains stimulating (note her fieldnotes from Shanxi and Shaanxi, pp.198–217). Indeed, her 2000 article on Jicun in Ritual and social change contains more material on changing temple life there than does her 2013 book.

While she has moved on from ritual to broader social issues, she recognizes the importance of both religion and religious studies in China. I think of de Martino‘s fieldwork on taranta in south Italy, also engaging with the plight of the sufferers.

Guo Yuhua sees religion and myth as behaviour with long historical roots to explain the world, a kind of survival technique. (cf. Ju Xi). In an email she notes similarities with the CCP’s enforced belief system:

If the latter is as “scientific” as they claim, then it too should be subject to corroborating or refuting; it should be explored, debated, doubted, critiqued. But the current reality is that it demands unconditional veneration as an item of faith, even written into the constitution—a totally illogical position.

Religious studies should take account of such [sociological] approaches, rather than mere descriptive documentation or “salvage”—viable cultures will endure and evolve without such measures. Given the importance of religion in society, as long as studies takes account of its social basis, then it’s a worthy discipline.

As she observed in interview, alluding to the Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft debate,

If you say, Chinese tradition is such a society of rites and customs (lisu 礼俗), not of legal rationality (fali 法理), then its distinctive feature is human governance. To be satisfied with this explanation is to shirk responsibility, because if everything goes back to the ancestors, then what is there for us to do? If one wants true reform, I think we have to start from the institutional level, so naturally we have to transfer our attentions towards institutions, or more precisely, the interactive configuration of culture and human nature.

Expressive culture

My taste of fieldwork with Guo Yuhua stimulated my own quest to relate local expressive cultures to politics and society—a common goal of ethnomusicologists, but much less commonly achieved for China (in another post I lead from the state’s persecution of human rights lawyers to the tendency of anthropologists and ethnomusicologists to speak up for oppressed minorities).

On one hand, the study of imperial China is eminently necessary, but for many Chinese scholars it has had the added attraction of being relatively safe (cf. former Yugoslavia). Studies of culture and ritual, too, tend to be an autonomous zone into which social change since 1900 rarely intrudes.

As the state has receded somewhat since the 1980s, it may seem slightly less risky to document the current fortunes of folk genres, though this too often descends into a simplistic lament about the lack of a new generation; and as the overall society certainly becomes more affluent, those stark social problems that do remain continue to be taboo. So we accumulate dry lists of ritual manuals and sequences, vocal and instrumental items, and birthdates of performers.

Meanwhile, social and political change is often seen only through the lens of “revolutionary” culture, while living (or at least only semi-moribund) traditional vocal and instrumental genres are imprisoned in museums and libraries, and their performances sanitised for the concert platform. Their history under Maoism is blandly encapsulated by listing a few isolated performances at secular regional festivals, along with a standard clichéd sentence on the “mistakes” of the Cultural Revolution.

Guo Yuhua tellingly describes the replacement of traditional ritual culture by that of political campaigns—although in my Shaanbei book I note the enduring strands of tradition even through the years of Maoism. While the lives of blind bards and shawm players feature in her account, I think my own focus on them in my book still makes a useful supplement.

Li Huaiqiang, 1999.

In my survey of itinerant storytellers in Shaanbei, my accounts of the changing fortunes of the village’s blind bard Li Huaiqiang (1922–2000, known as “Immortal Li”, Li xian) also derive from Guo Yuhua’s close relationship with him (see my Ritual and music of north China, vol.2: Shaanbei). As this article grows, I’ve written about him and other bards in a separate post.

Another major theme of my Shaanbei book, and the accompanying DVD (§B, cf. my comments on the funeral clip from Wang Bing‘s recent film), is the village’s shawm band. Such bands belong to the traditional litany of social outcasts. One of Guo Yuhua’s main informants is Older Brother, the sweet semi-blind shawm player who features in my own book and DVD (cf. blind shawm players in Yanggao, north Shanxi).

Yangjiagou funeral, 1999. Older Brother second from left.

While I was filming the procession to the hilltop grave, setting off before dawn, Guo Yuhua was taking photos:

In a society where no matter how desperate people were, even vagrancy offered no hope (p.162), Older Brother tells Guo Yuhua how, with his family starving, he reluctantly went on the road begging in the second half of 1968 (pp.133–4, 193–6), led by a sighted old man from a martyred revolutionary family. In a moving account, he tells how they went on a long march throughout Shaanbei, sleeping rough; they were treated kindly on the road, learning to beg for scraps. When conditions allowed simple funerals, he even played his shawm, his companion accompanying on cymbals. He would find people to write letters home to his father to reassure him he was still alive. By the winter he had found a rather secure village base where he was hopeful of eking a living, but this enabled his father to track him down and summon him home.

It may seem ironic to cite Mao here, but as he observed,

There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake, art that stands above classes, art that is detached from or independent of politics.

So did the socialist arts Serve the People, meeting their needs? Whose needs do state propaganda units like the Intangible Cultural Heritage serve now? Of course, while the state has its own agenda for the latter, local actors can utilize it to achieve their own requirements, as several scholars have observed (and that is perhaps the only thing that can be said for it).

As I suggested in my post on the recent film of Wang Bing, this is the context in which we blithely analyse the scales, melodies, and structures of Chinese music. Primed with Guo Yuhua’s book, you’ll never again want to read the bland reified propaganda from the ICH.

* * *

In her book, as in her whole scholarly output, Guo Yuhua makes a rational and forceful indictment based on detailed evidence, a passionate plea for heeding the voices of ordinary people and rewriting history.

All this may be a rather familiar story abroad (from individual studies like those of Chan, Madsen, and Unger (Chen village), Friedman, Pickowicz, and Selden’s two volumes on Wugong, Jing Jun’s The temple of memories, my own Plucking the winds and Daoist priests of the Li family, or the broader brush of Frank Dikötter—I hardly dare mention the few apologists like William Hinton and Mobo Gao, to whom Guo Yuhua gives short shrift). But it feels yet more incisive coming from PRC scholars, and her research is both detailed and amply theorised. The only aspect where the stories of Chen village and Wugong may make more impact is that they follow individual lives, whereas most of Guo Yuhua’s citations are anonymised.

While her work such as that on “Jicun” exposes the tragic failures and outrages of the Maoist decades, she is also relentless in denouncing current abuses—always upholding the values of social justice and the liberation of the sufferers, inspired by the same concern for the welfare of Chinese people that once made the CCP popular. (For my own nugatory contribution to Xi Jinping studies, see here, and even here.)

I seem to be suggesting a rebalancing from the newly-revived Guoxue 国学 (“national studies”: traditional Chinese culture, especially Confucianism) towards Guoxue 郭学 (Guo Yuhua studies). She bridges the gap between politics, anthropology, and cultural studies. Whether you’re interested in society, civil rights, history, music, or ritual, let’s all read her numerous publications—and do follow her on social media.

[1] Many of her important articles are collected here, including several related to her work in Shaanbei. For another major recent article, see here (or here). For a brief yet penetrating and indignant essay, try “OMG, not that stupid ‘happiness’ again?!” My thanks to Guo Yuhua, Stephan Feuchtwang, Harriet Evans, and Ian Johnson for further background.

[2] For a translation of Sun’s recent article, soon blocked from WeChat, see here. For a useful English account of the Tsinghua group, see here; and yet another fine anthropologist there is Jing Jun 景军. For Wang Mingming at Peking University just up the road, click here.

[3] §4 of which was translated by Harriet Evans as “Narratives of the ‘sufferer’ as historical testimony”, in Arif Dirlik et al. (eds.). Sociology and anthropology in twentieth-century China: between universalism and indigenism (Hong Kong: Chinese University, 2012), pp.333–57.

[4] Guo Yuhua notes that traditionally women’s main opportunity for public interaction was at the 3rd-moon temple fair for Our Lady, but I wonder if their exclusion from the ritual sphere was so severe: female spirit mediums had been, and still are, a major element in ritual life.

[5] The silence of the 1993 Mizhi county gazetteer on the privations and indignities of the Maoist decades makes the frank accounts in the Yanggao gazetteer (also 1993) all the more impressive: see my Daoist priests of the Li family, e.g. pp.100–101, 123.

[6] Hinton, in his classic Fanshen, also documents complexities, but within an overall positive tone.

[7] I’m not sure how rare this is in academia, but it has been adopted by novelists such as Li Rui and Liu Zhenyun. In Sun Peidong’s review she cites Han Shaogong’s novel A dictionary of Maqiao (Maqiao zidian 马桥词典), set in Hunan, for its unpacking of local language. For Shaanbei dialect, cf. the 2007 book Tingjian gudai 听见古代 by Wang Keming 王克明. For film documentaries, click here.

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu. But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the

But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the

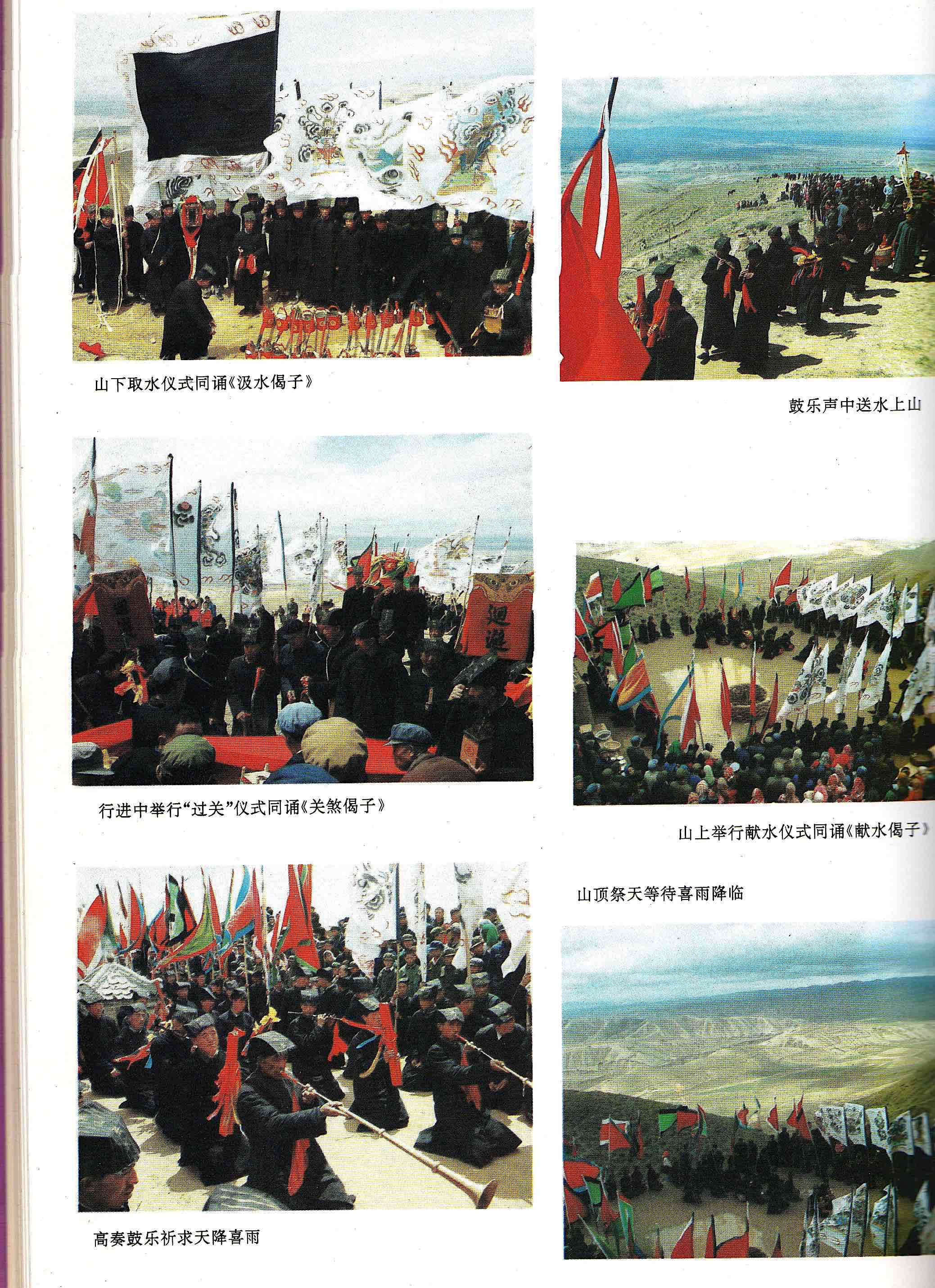

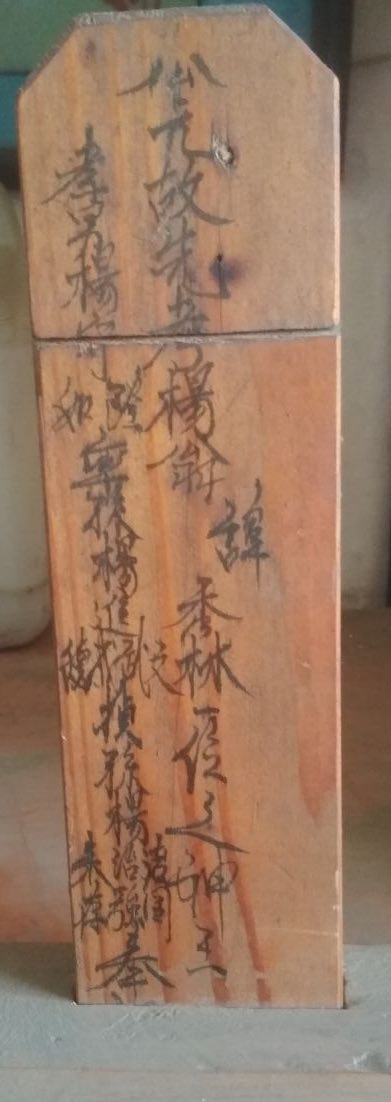

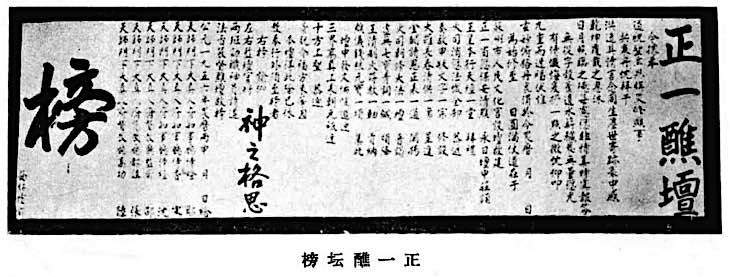

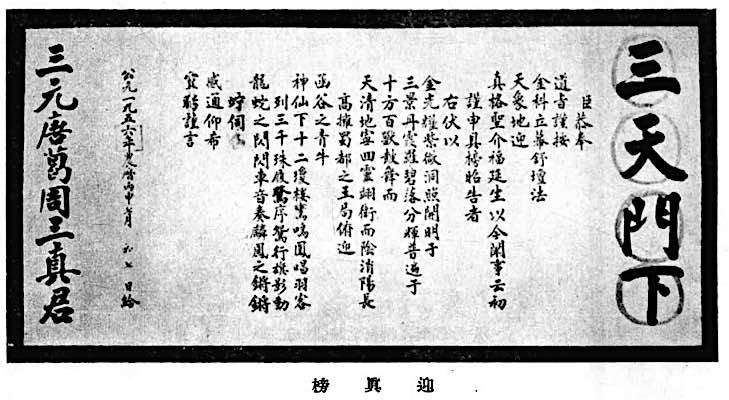

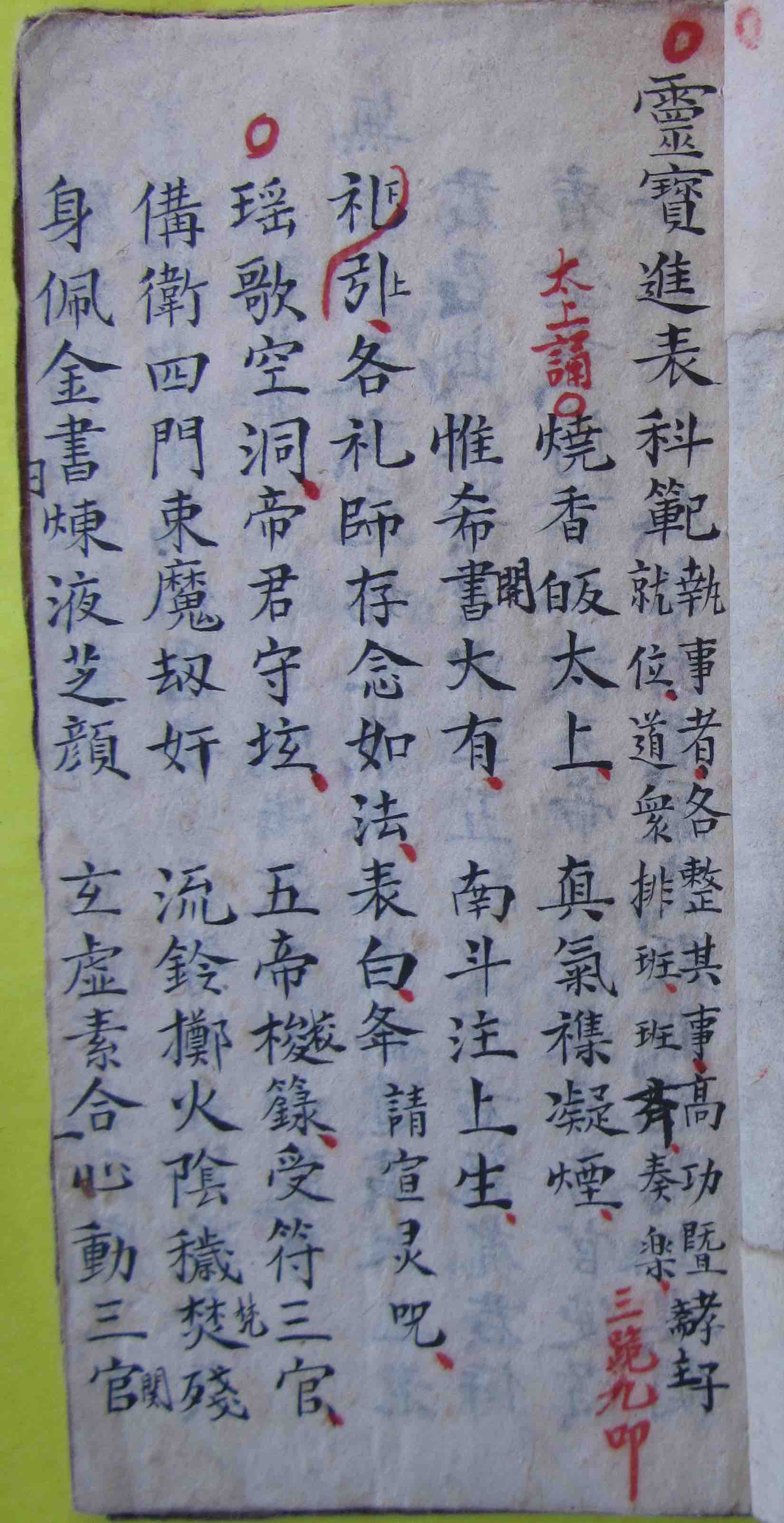

Placards proclaiming the Offering ritual.

Placards proclaiming the Offering ritual.

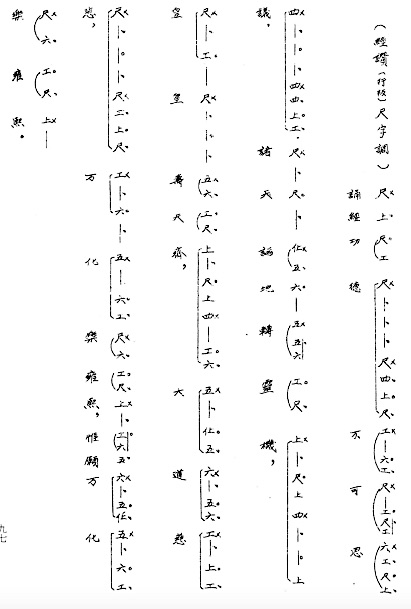

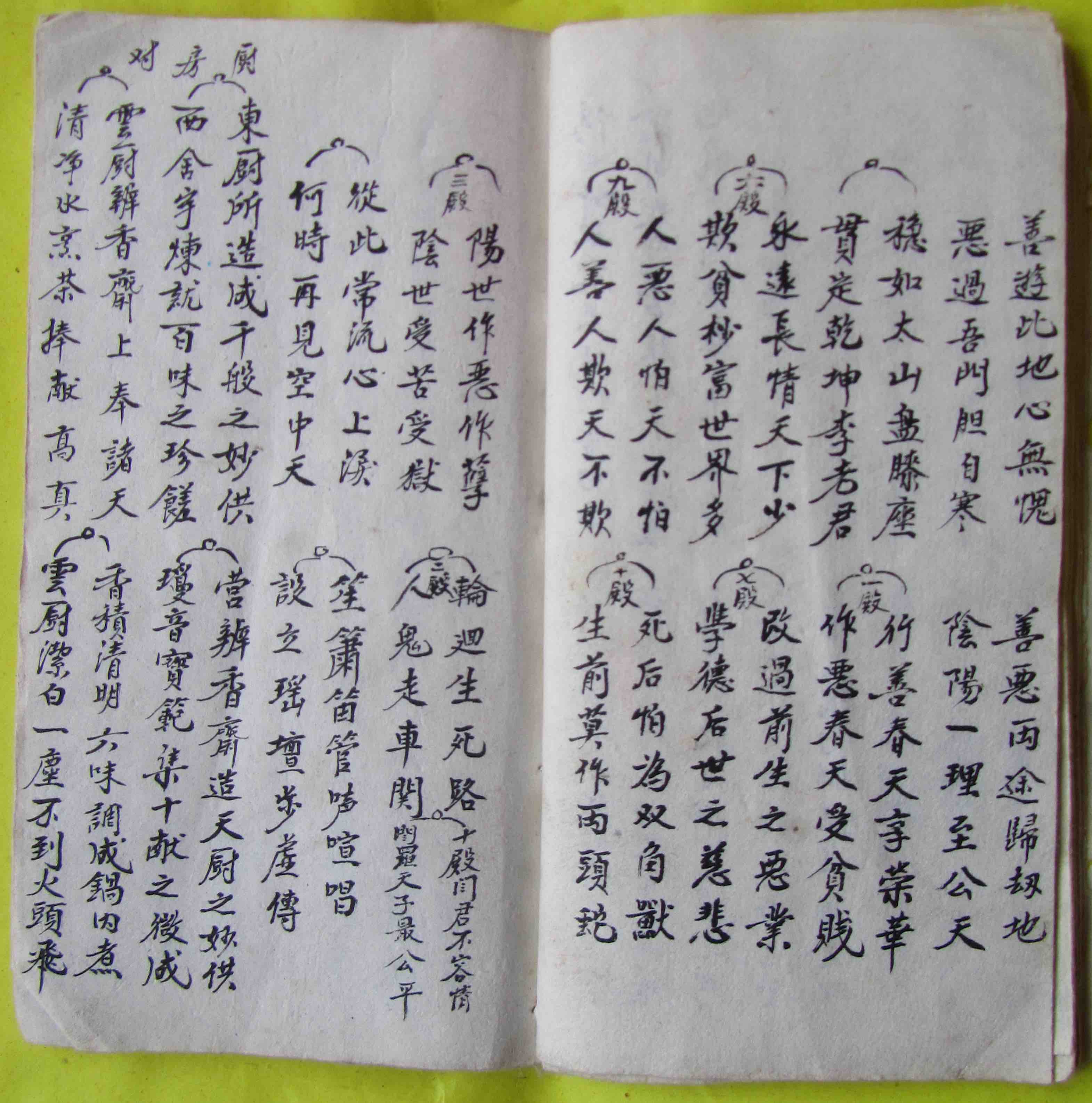

Opening of Songjing gongde, a widely used hymn in both temple and household Daoist groups.

Opening of Songjing gongde, a widely used hymn in both temple and household Daoist groups. Opening of Quanbiao ritual: instrumental Yifeng shu leading into Tianshi song hymn, whose text is the generational poem for the priestly lineage.

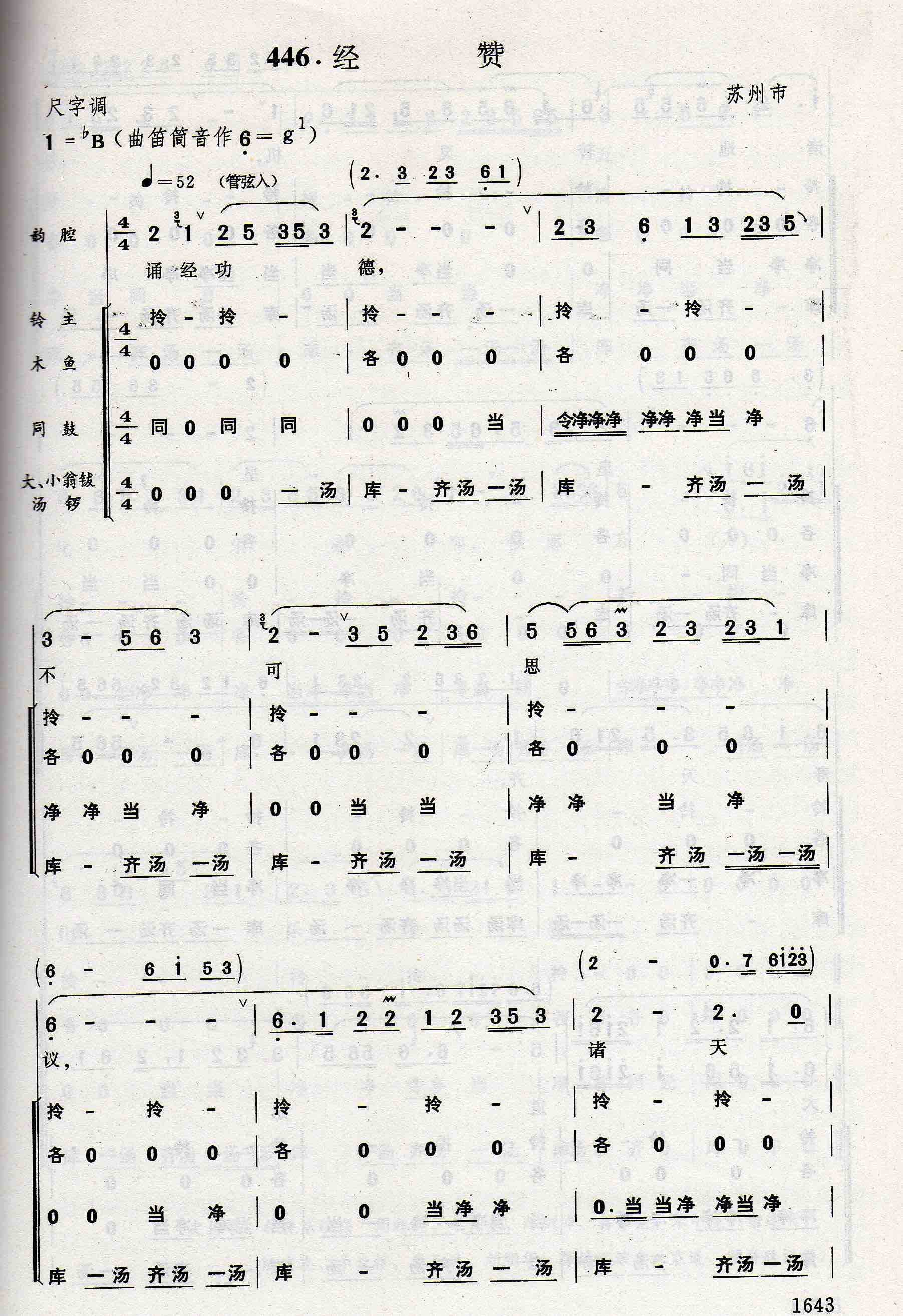

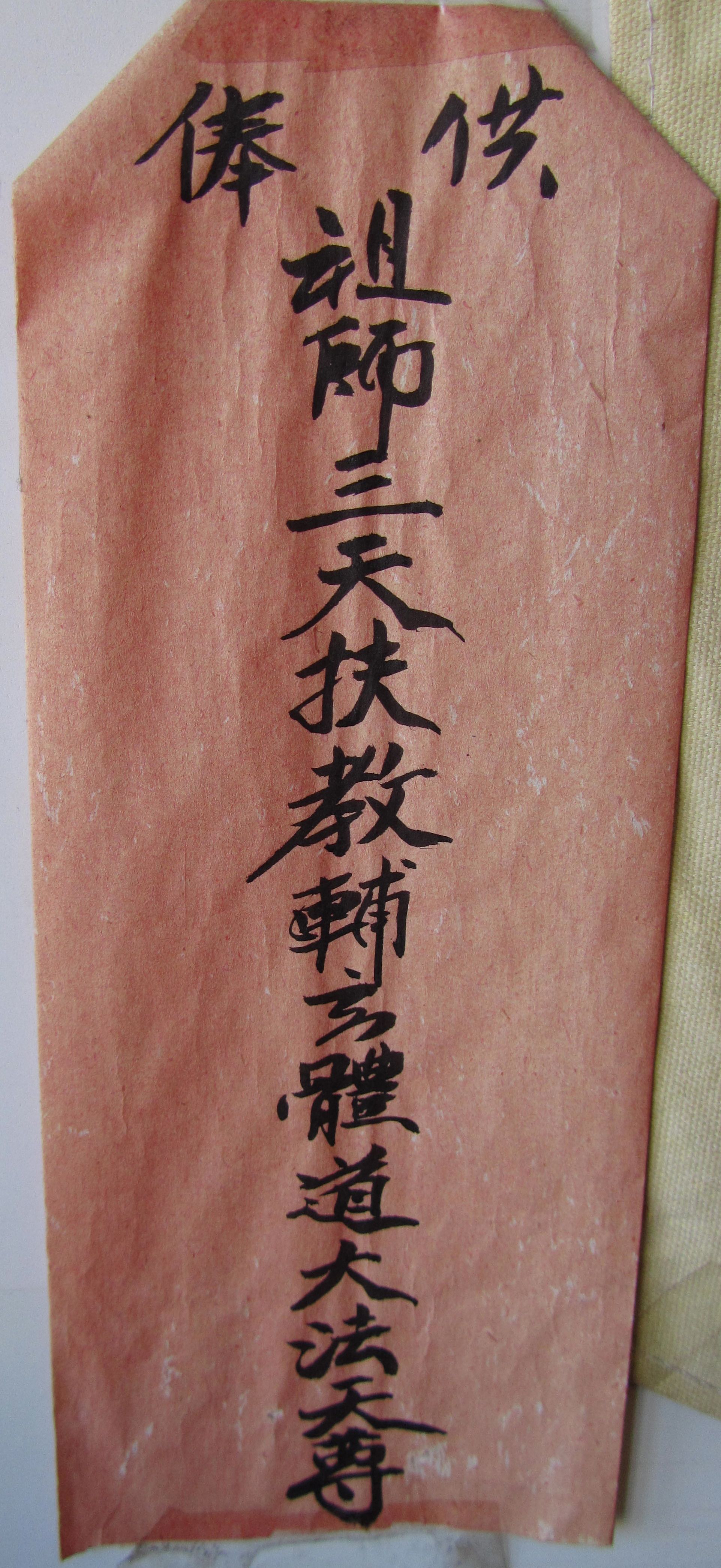

Opening of Quanbiao ritual: instrumental Yifeng shu leading into Tianshi song hymn, whose text is the generational poem for the priestly lineage. Opening of Songjing gongde hymn, transcribed by Anthology collectors from a 1990s’ rendition, also showing percussion accompaniment.

Opening of Songjing gongde hymn, transcribed by Anthology collectors from a 1990s’ rendition, also showing percussion accompaniment. Tianshi song hymn as transcribed by Anthology collectors.

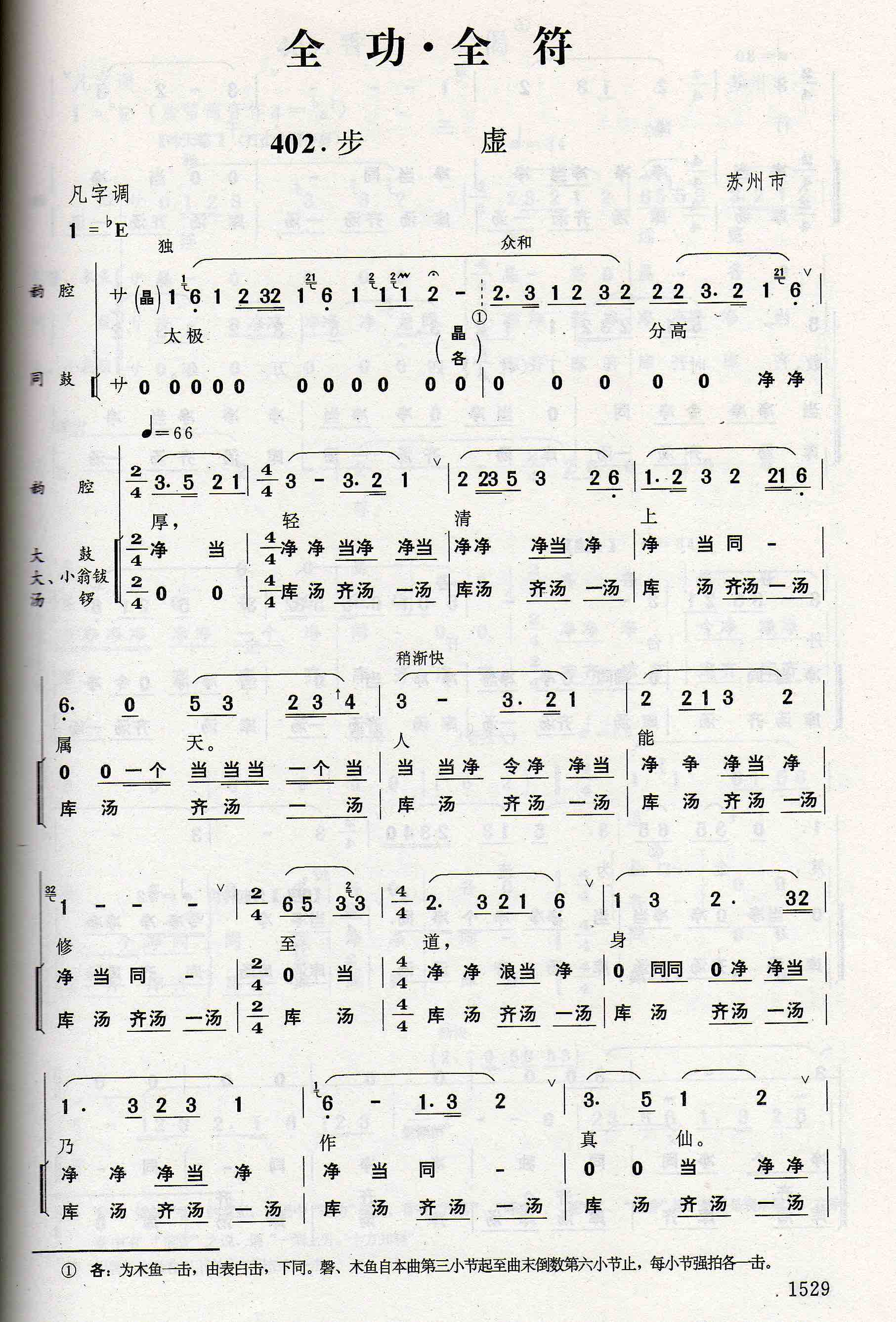

Tianshi song hymn as transcribed by Anthology collectors.

Opening of Taiji fen gaohou hymn as transcribed in the Anthology.

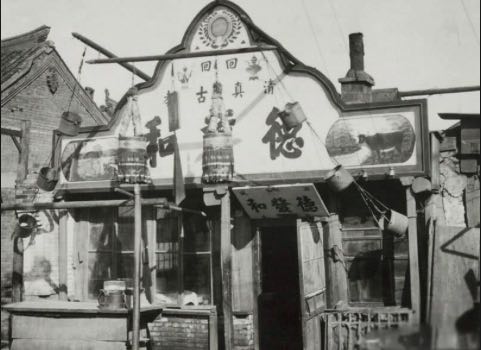

Opening of Taiji fen gaohou hymn as transcribed in the Anthology. The Wanhe tang:

The Wanhe tang:

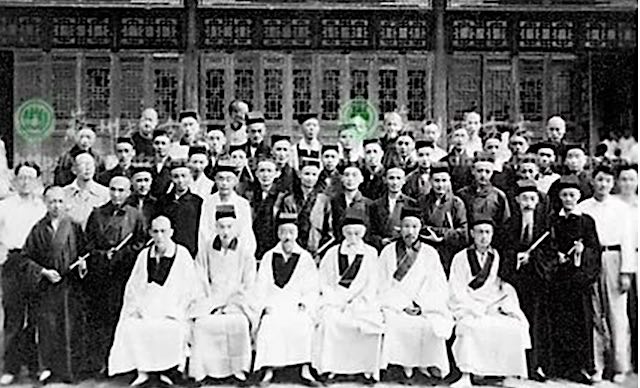

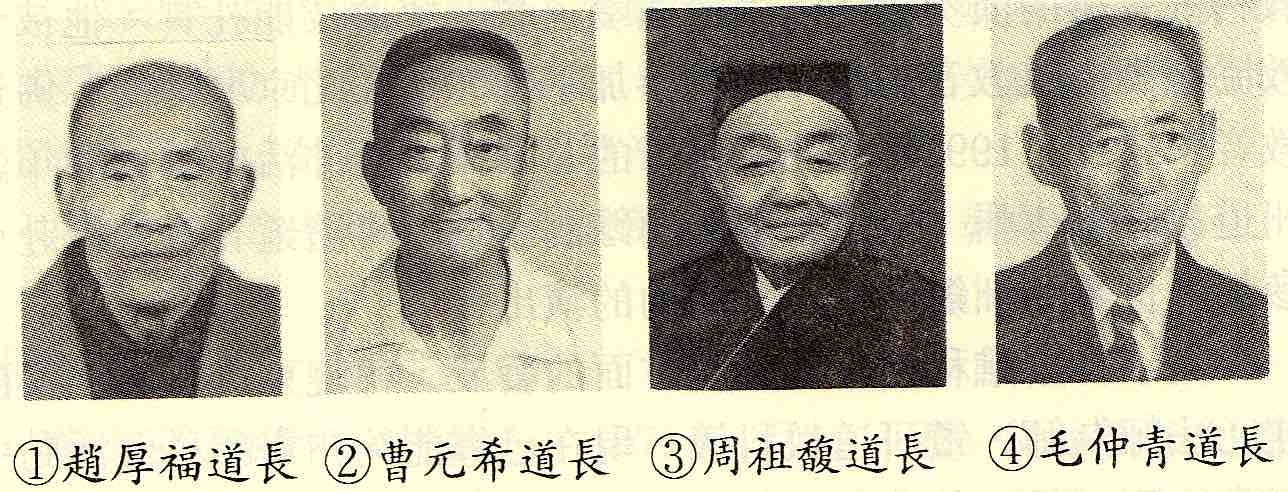

Daoists of the Daode guan temple, Zhangye county;

Daoists of the Daode guan temple, Zhangye county;