I’ve often cited Nicolas Slonimsky’s brilliant Lexicon of musical invective. So I enjoyed reading his fascinating memoir

- Perfect Pitch,

in a revised third edition from 2023, ably edited by his daughter Electra Slonimsky Yourke.

Written with wit and wisdom at the age of 94, and first published in 1988, it’s a captivating blend of substance and gossip, packed with wonderful anecdotes—a Who’s Who of figures that seemed to matter at the time, part of a niche zeitgeist.

Nicolas Slonimsky (1894–1995) (fine website, with A/V; books, including Writings on music, 4 vols., 2005; wiki) was “a typical product of the Russian intelligentsia”—in the early chapters he gives a detailed account of his Russian family history and political turmoil. Already by 1912 his early musical facility led him to describe himself as a “failed wunderkind”.

In autumn 1918 he left St Petersburg. After stays in Kiev and Yalta, in 1920 he reached Constantinople (pp.85–90), where he found many musicians among the throng of Russian refugees. Lodging with a Greek family, he accompanied Russian dancers, and played for restaurants and silent movies. He composed Obsolete foxtrot and Danse du faux Orient, later included in his Minitudes. After following a girlfriend, a Russian dancer, to Sofia, by late 1921 he arrived in Paris—also inundated by Russian emigrés. There he worked for Serge Koussevitzky for the first time, who introduced him to Stravinsky in Biarritz. Koussevitzky, sorely challenged by irregular time signatures, * asked him to rebar The Rite of Spring for him. Despite moving in cultured circles, Koussevitzky (like Tennstedt later) was not a great reader.

Slonimsky was impressed by Nikolai Obukhov, a “religious fanatic” who made a living as a bricklayer. Inspired by Scriabin, and an unlikely protégé of Ravel, his magnum opus Le livre de vie for voices, orchestras, and two pianos (Preface here) contained “moaning, groaning, screaming, shrieking, and hissing”. He dreamed of “having his music performed in an open-air amphitheatre, perhaps in the Himalayas or some other exotic place”. He developed the croix sonore, a prototype of the theremin.

In 1923 Slonimsky docked in New York, travelling on a Nansen passport, “an abomination of desolation, the mark of Cain, the red spot of a pariah”. He soon found work as opera coach for the new Eastman School of Music in Rochester, at the invitation of Vladimir Rosing. He now confronted the challenge of learning English. Indeed, the book is full of gleeful comments on language learning. Taking advertising slogans as his textbook, Slonimsky’s arrangements (particularly Children cry for Castoria!) became popular. America seemed a fairy-tale land. At Eastman he found a kindred soul in author Paul Horgan.

In 1924 Koussevitzky replaced Pierre Monteux as conductor of the Symphony Orchestra (whose musicians were mainly German, French, and Russian), and the following year he invited Slonimsky to become his secretary (feeling more like a “serf”). Koussevitzky was in awe of Rachmaninoff’s genius, and despite his withering assessments of rival conductors, he did promote Mitropoulos and Bernstein; he was dismissive of Arthur Fiedler’s Boston Pops (cf. the splendid Erich Leinsdorf story). Much as he valued Slonimsky’s talents, his insecurity meant that his young protégé always had to tread carefully, and in 1927 they parted company.

Still, he now enjoyed a “meteoric” conducting career. With no illusions about his rudimentary technique, he founded the Chamber Orchestra of Boston, promoting contemporary composers—notably Henry Cowell, Edgard Varèse, and Charles Ives. After a performance of a work by Cowell, they rejoiced in the headline “”Uses egg to show off piano”. Slonimsky introduced Aaron Copland to George Gershwin. After Cowell introduced Slonimsky to Charles Ives, they became close.

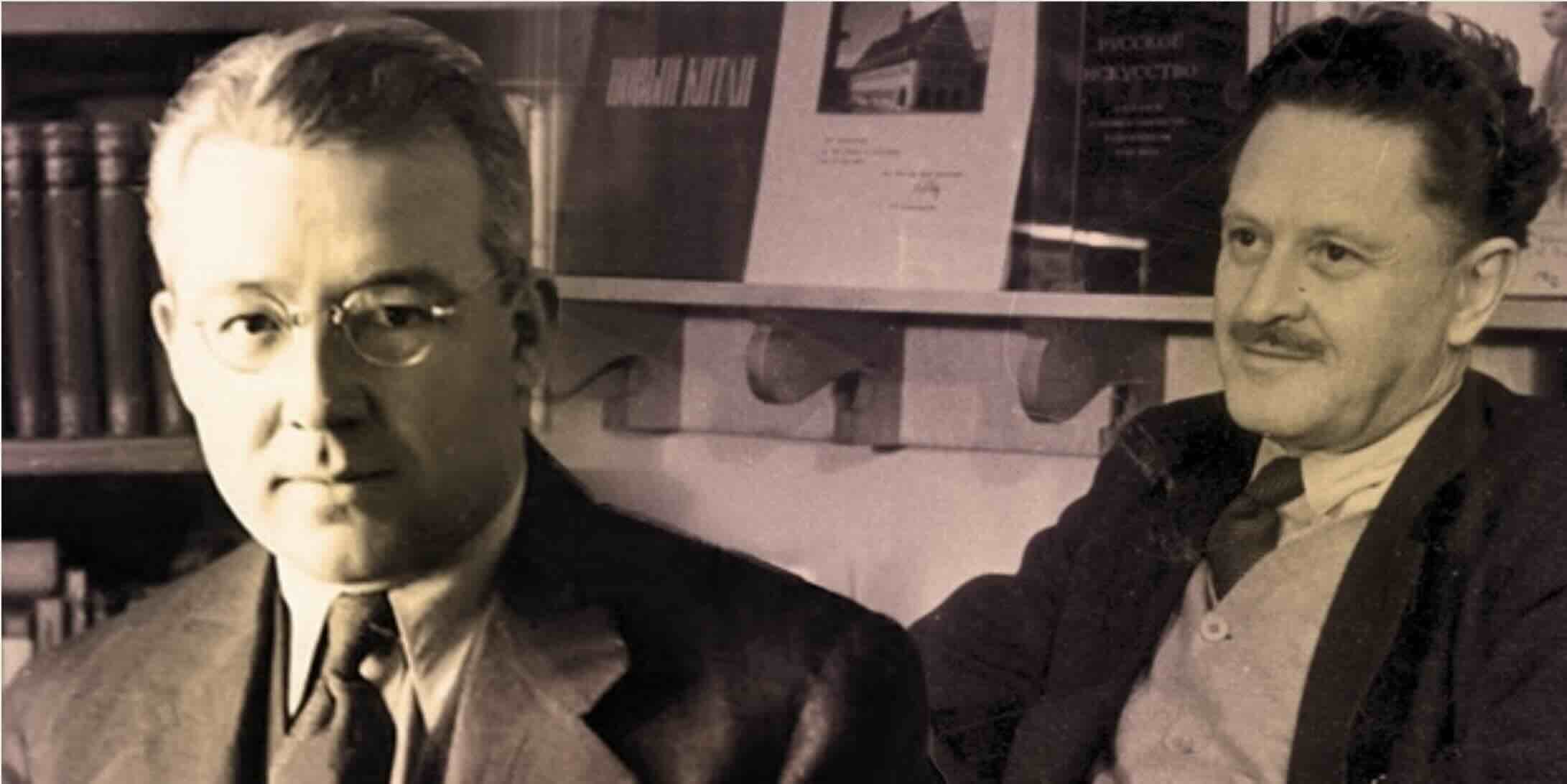

Henry Cowell with Charles Ives, 1952.

Slonimsky was full of praise for Ives:

I learned to admire the nobility of his thought, his total lack of selfishness, and his faith in the inherent goodness of mankind. […] He inveighed mightily against self-inflated mediocrity, in politics and art alike. The most disparaging word in his vocabulary was “nice”. To him, it signified smugness, self-satisfaction, lack of imagination. He removed himself from the ephemeral concerns of the world at large. He never read newspapers. He did not own a radio or a phonograph, and he rarely if ever attended concerts.

In 1931 (the year he gained US citizenship), Slonimsky gave the première of Ives’s Three places in New England in New York. Promoting the work with passion, in Perfect pitch he waxes lyrical about its genius.

Slonimsky conducting Varèse’s Ionisation in Havana.

Slonimsky conducting Varèse’s Ionisation in Havana.

He was invited to conduct in Havana, his first experience of modern Cuban music. He conducted revelatory concerts in Paris, sponsored by Ives, encouraged by Varèse. There too he married Dorothy Adlow.

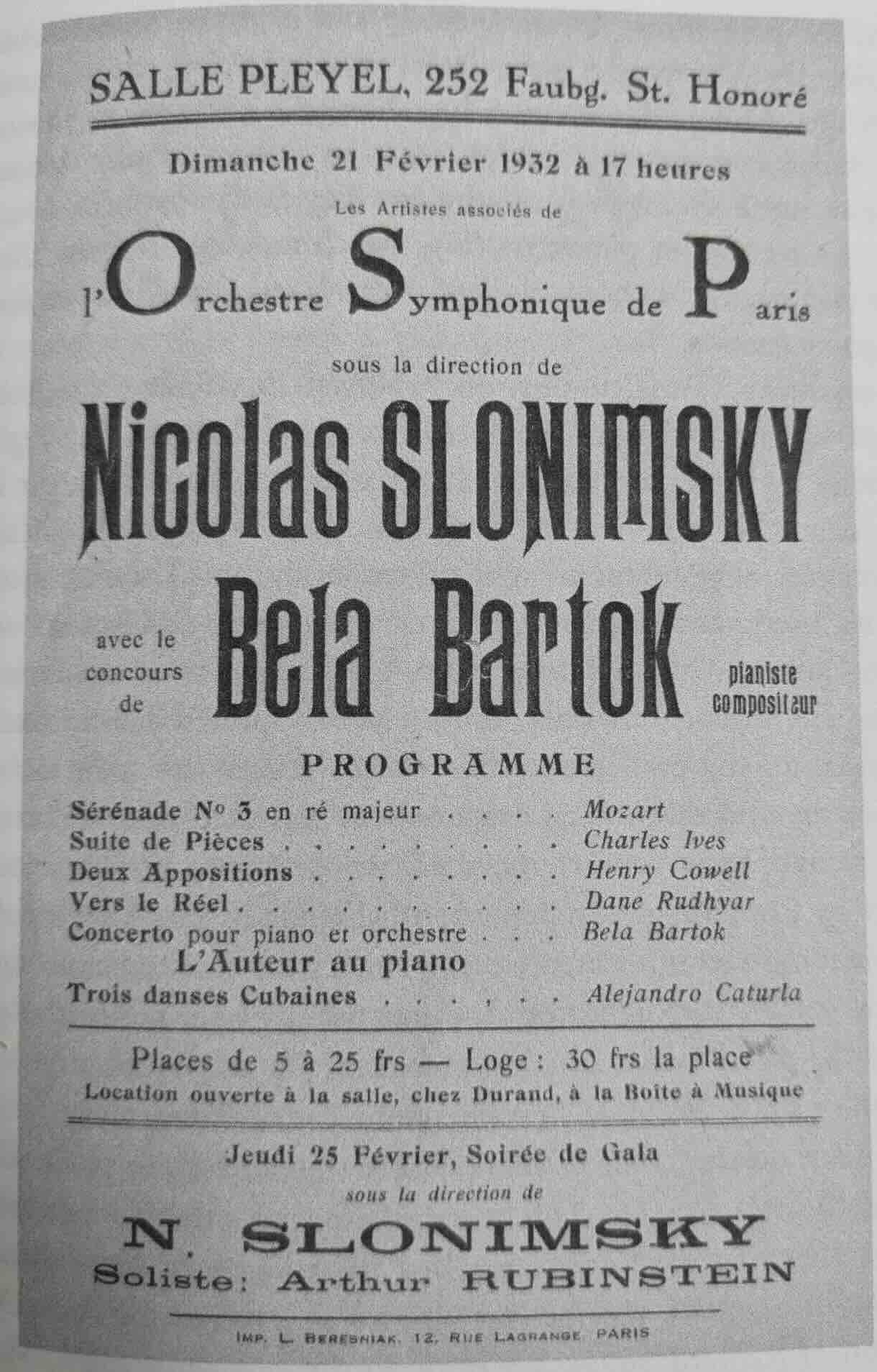

He returned to Europe for more concerts in 1932—with Bartók giving the Paris premiere of his 1st piano concerto, and Rubinstein playing Brahms’s 2nd piano concerto!!! In Berlin (in the nick of time before the grip of Nazism) he conducted the Berlin Phil in a modern programme including Three places in New England and Varèse’s Arcana. He repeated the programme in Budapest.

He reflects on this ephemeral phase of his career:

The art of conducting is paradoxical, for its skills range from the mechanical to the inspirational. A conductor can be a semaphore endowed with artificial intelligence, or an illuminating spirit of music. The derisive assertion that “anyone can conduct” is literally true: musicians will play no matter how meaningless or incoherent the gestures of a baton wielder may be. In this respect, conductors stand apart from other performers. A violinist, even a beginner, must be able to play on pitch with a reasonable degree of proficiency. A pianist must have enough technical skill to get through a piece with a minimum of wrong notes. But a conductor is exempt from such obligations. He does not have to play; he orders others to play for him.

This leads him to some wonderful stories about badly-behaved conductors (cf. Viola jokes and maestro-baiting); Toscanini, Klemperer—and this story, evoking the unwelcome posturings of many a later maestro:

Mengelberg once apostrophised his first cello player with a long diatribe expounding the spiritual significance of a certain passage. “Your soul in distress yearns for salvation,”, he recited. “Your unhappiness mounts with every passing moment. You must pray for surcease of sorrow!” “Oh, you mean mezzo forte,” the cellist interrupted impatiently.

I’m eternally grateful to Slonimsky for relating some classic Ormandy maxims (now joyously expanded here by members of the Philadelphia orchestra)—OK then, just a couple:

Suddenly I was in the right tempo, but it wasn’t.

Who is sitting in that empty chair?

In “Disaster in Hollywood” he tells how his first appearance with the LA Phil in 1932 ended in tears. When the programmes for his eight-week season at the Hollywood Bowl in the summer of 1933 proved far too challenging for the “moneyed dowagers”, his conducting career came to an inglorious end. He takes consolation in the later admission of the works that he championed to the pantheon (cf. the fine story of Salonen’s interview for the LA Phil!). Meanwhile in New York he conducted, and recorded, Varèse’s revolutionary Ionisation.

With typical linguistic flourishes, he devotes a proud chapter to the birth of his daughter Electra, editor of the volume. He rearranged a limerick:

There was a young woman named Hatch

Who was fond of the music of Batch

It isn’t so fussy

As that of Debussy

Sit down, I’ll play you a snatch.

He would have enjoyed these limericks, and one by Alan Watts, n.2 here.

“Like gaseous remnants of a shattered comet lost in an erratic orbit”, occasional conducting engagements still came his way. In “Lofty baton to lowly pen” he recalls his transition to musical lexicography. He met fellow Russian emigrés Léon Theremin (whose life was to take a very different course) and the iconoclastic theoretician Joseph Schillinger. As Slonimsky compiled his book Music since 1900 (1937!), he became interested in the savage reception of new music, leading to his brilliant Lexicon of musical invective.

Still, he was never tied to his desk. His appetite whetted by his trips to Cuba, in “Exotic journeys” he recalls his 1941–42 tour of Brazil (hearing Villa Lobos’s tales of his Amazonian adventures), Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Columbia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Mexico. His book Music of Latin America was published in 1945.

Returning to Boston, he was plunged into family duties. In 1947 he published Thesaurus of scales and melodic patterns.

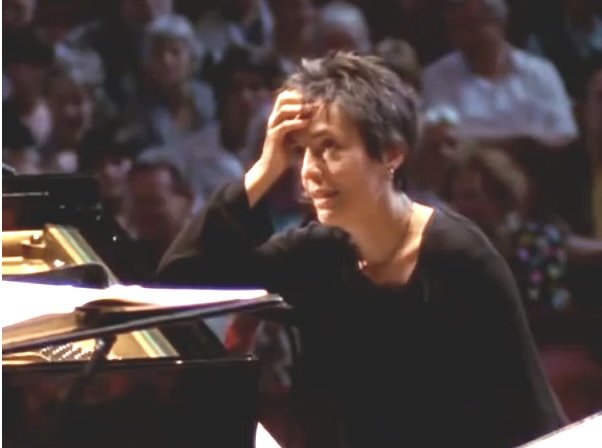

In 1935, armed with a US passport, he returned to his birthplace, now called Leningrad, visiting long-lost relatives. He reflects on the death of his mother in 1944, and the life of his aunt Isabelle Vengerova (1877–1956), who became a legendary piano teacher in the States.

After the war, with Russia in vogue in the USA, Slonimsky enjoyed revising his proficiency in his mother tongue, updating old manuals to teach students and taking on work as translator. While he was largely free of McCarthyite suspicion of sympathising with Communism, back in the USSR his brother Michael was at far greater risk for being suspected of opposing it (for Soviet life, note The whisperers).

Dissatisfied with previous compendia and nerdily meticulous, he found a new mission in updating Baker’s biographical dictionary of musicians. He was proud of his 1960 article “The weather at Mozart’s funeral”. In 1956 he achieved unprecedented celebrity through appearing on the quiz show The big surprise.

In “The future of my past” he describes another trip to the USSR and the Soviet bloc in 1962–63, funded by the State Department—an Appendix to the third edition provides a detailed account. He visited Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, as well as Greece and Israel. On his meetings with musicians, he was inspired by the energy of Ukrainian and Georgian composers.

His diary is punctuated by his curiosity about language, starting in Moscow:

To my Americanised ears, the new Soviet language sounded almost theatrical in its emphasis, deliberate articulation, and expressive caesuras. I also noticed a proliferation of diminutives….

In Prague he learned the vowel-less tongue-twister Strc prst skrz krk:

I used this phrase as the supposed title of a choral work by the mythical Czech composer Krsto Zyžik, whom I invented and whose name I was tempted (I ultimately desisted) to include as the last entry in my edition of Baker’s.

But soon after his return to Boston his wife Dorothy had a heart attack, which was to be fatal. Bereft after her death in January 1964, he welcomed the offer of a post at distant UCLA. He composed musical limericks for his students’ benefit, but was not always impressed by their aptitude, citing gems from their essays such as “A piano quintet is a piece for five pianos”.

After two seasons he reached compulsory retirement age, but he was never going to go quietly. In LA he enjoyed a wide social circle. Besides many “flaky” composer friends was John Cage, now a guru (Slonimsky cites Pravda: “His music demoralises the listeners by its neurotic drive and by so doing depresses the proletarian urge to rise en masse against capitalism and imperialism”!).

With John Cage, and Frank Zappa.

Back in LA, he made friends with Frank Zappa, who invited him to play at his gig.

Dancing Zappa, wild audience, and befuddled me: I felt like an intruder in a mad scene from Alice in Wonderland. I had reached my Age of Absurdity.

Meanwhile with perestroika in the Soviet Union, Slonimsky was becoming quite a celebrity there too, making several more visits and admiring composers’ creativity in new idioms.

* * *

Far more than a mere entertainer, Slonimsky was a major figure in promoting new music. With his eclectic tastes, I can’t help thinking that he would have enjoyed gravitating to ethnomusicology, questioning the wider meanings of “musician” or “composer” (see e.g. Nettl); but he was deeply rooted in the WAM styles of Russian classics and the American avant-garde. Still, within the world of WAM literature it makes a most fascinating memoir.

For some reason it fills me with joy to learn that a Japanese translation of Lexicon of musical invective has been published.

* Even 5/8 was too much for Koussevitzky:

He had a tendency to stretch out the last beat, counting “one, two, three, four, five, uh”. This ‘uh” constituted the sixth beat, reducing Stravinsky’s spasmodic rhythms to the regular heartbeat. When I pointed this out to him, he became quite upset. It was just a luftpause, he said. The insertion of an “air pause” reduced the passage to a nice waltz time, making it very comfortable to play for the violin section, who bore the brunt of the syncopation, but wrecking Stravinsky’s asymmetric rhythms.

To be fair, Koussevitzky did manage to conduct the 5/4 Danse générale of Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloé (1942 recording here; he first conducted it in 1928).

Source:

Source:

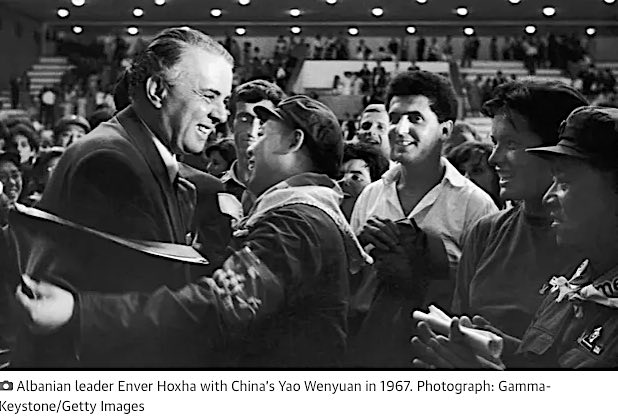

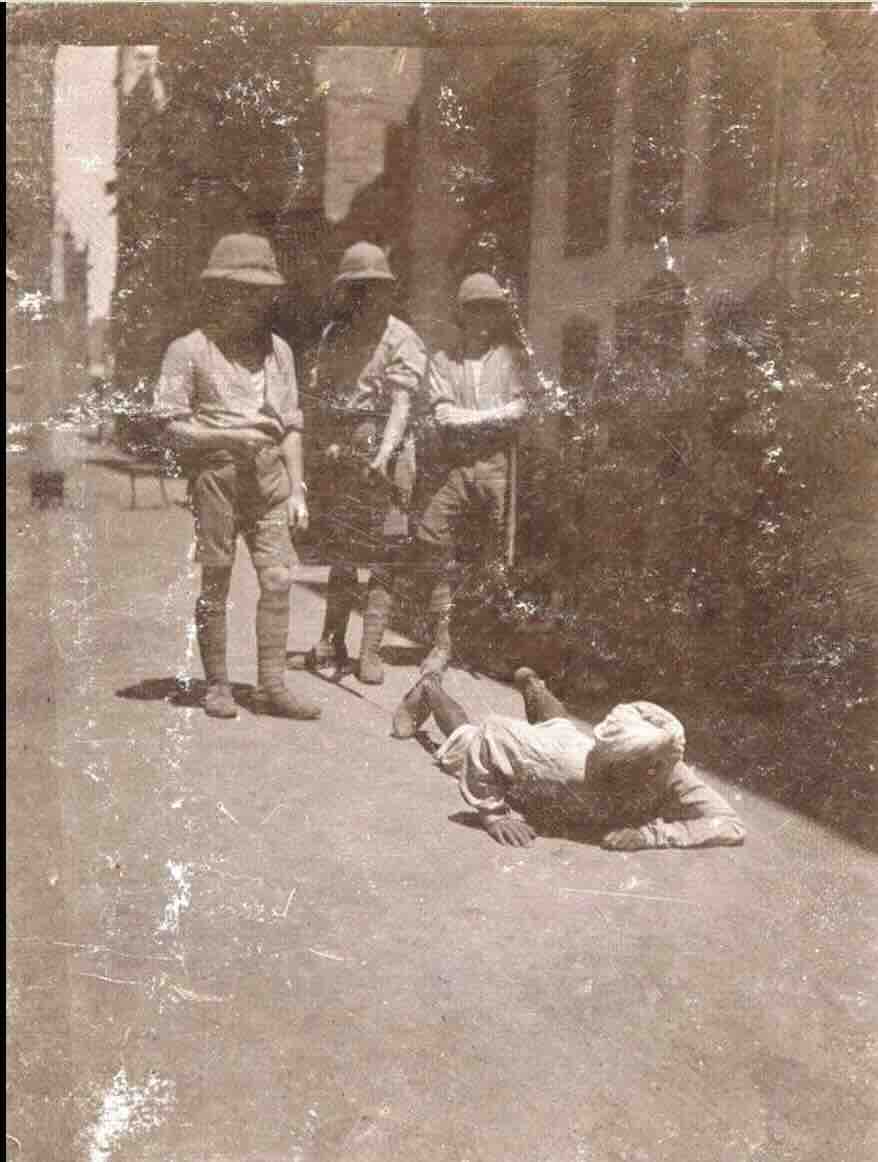

Prelude to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre (Amritsar):

Prelude to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre (Amritsar):

As to France, even I might hesitate to try out

As to France, even I might hesitate to try out

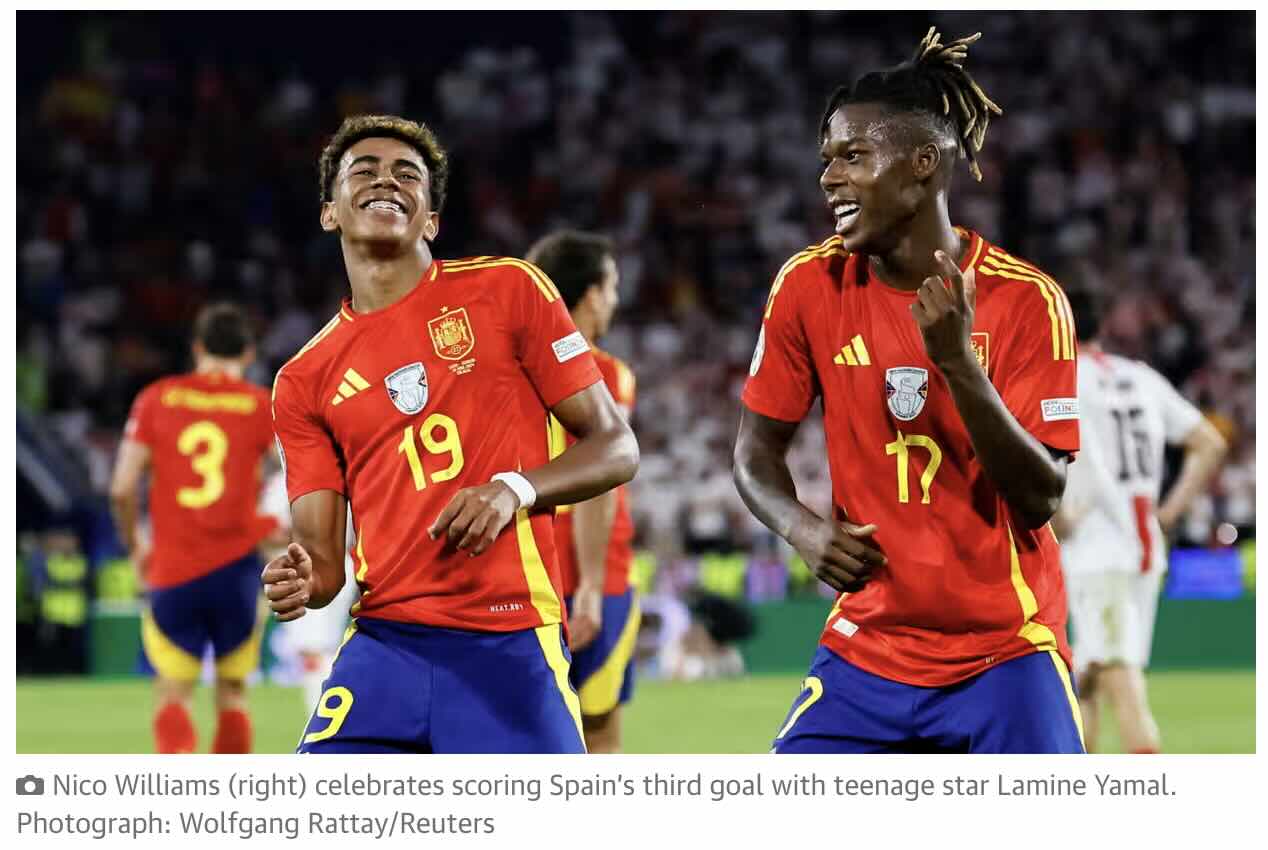

Not so much an impromptu pre-match party as

Not so much an impromptu pre-match party as

Grooving to the gaita. *

Grooving to the gaita. *

“Just dig that funky tulum“

“Just dig that funky tulum“

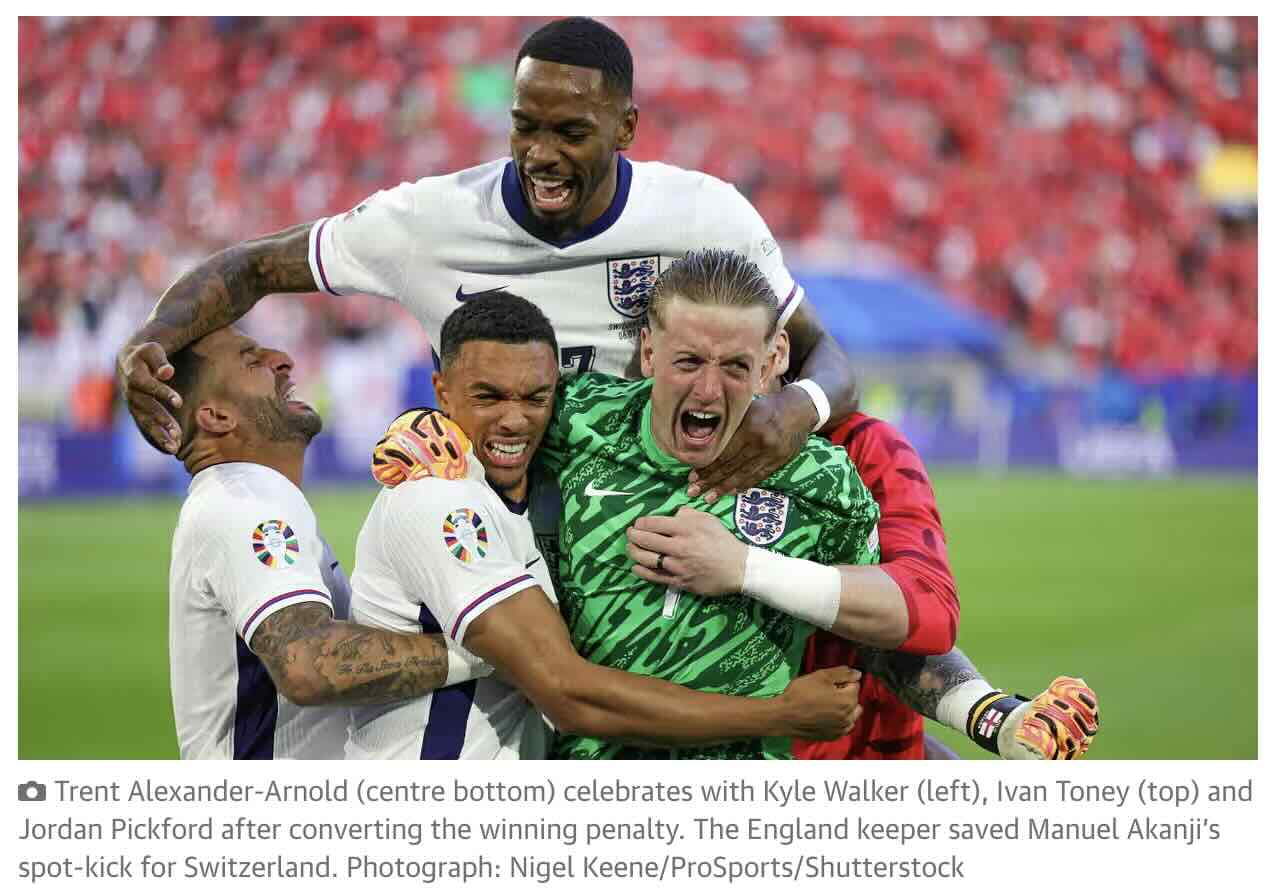

** Before England’s Great Escape from Slovakia, I was composing our own version of Caporetto, inspired by that popular classic from the

** Before England’s Great Escape from Slovakia, I was composing our own version of Caporetto, inspired by that popular classic from the

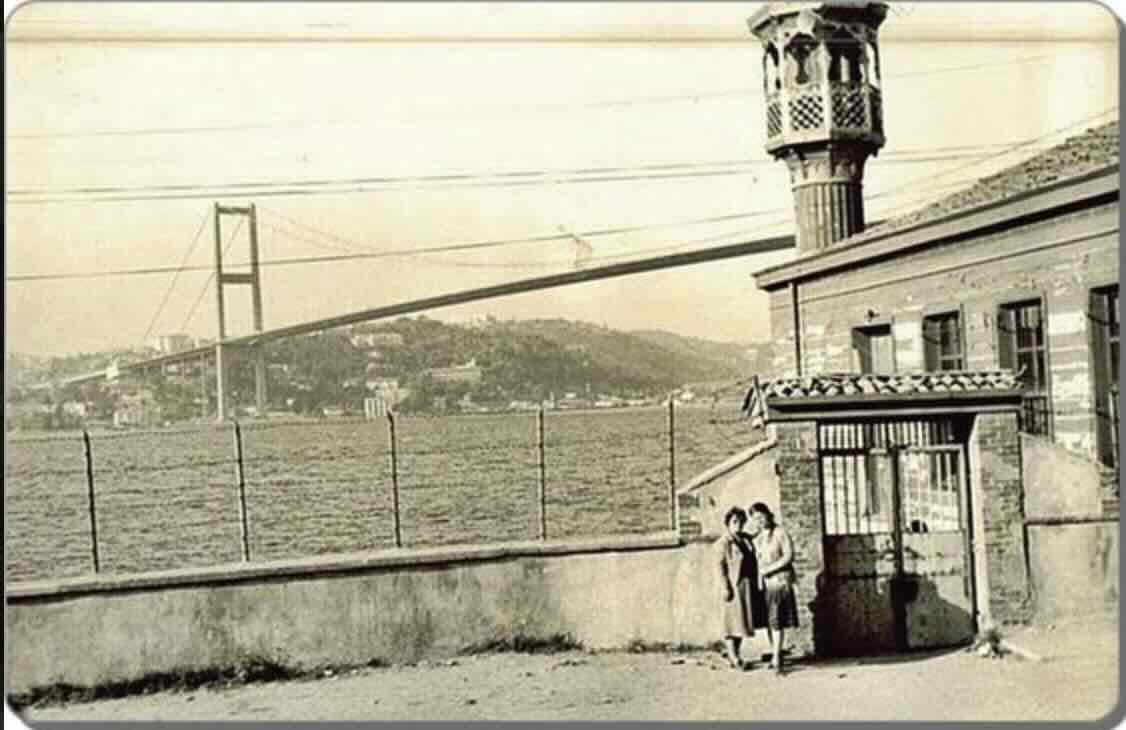

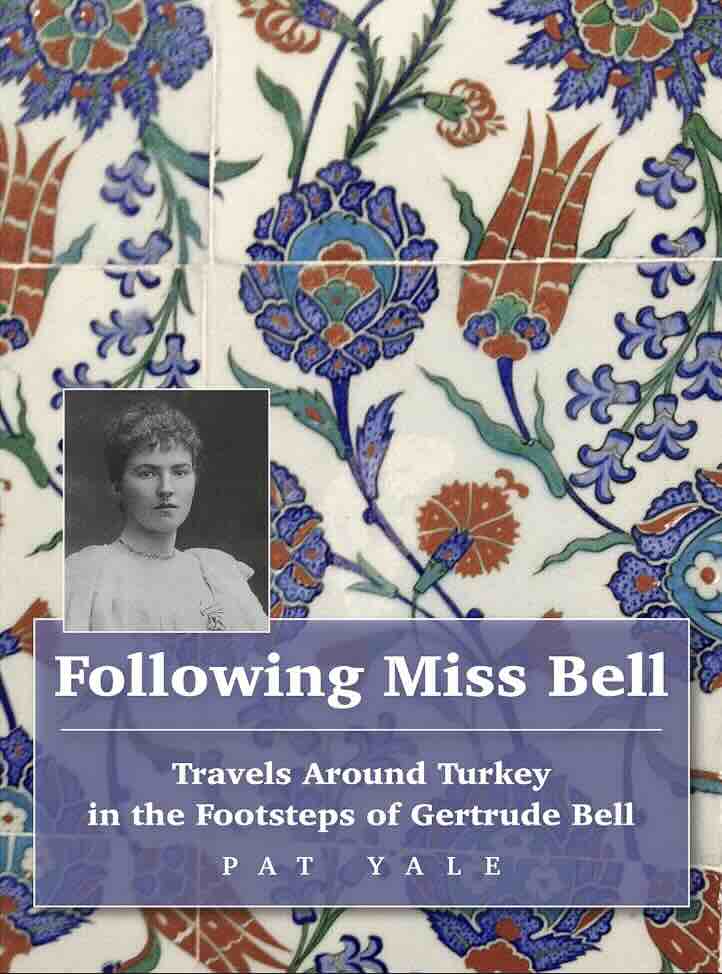

It’s taken me all this time to visit the bijou rectangular wooden mosque further up the coast towards the bridge—just below the mansion of Sultan Abdülhamid’s cultured confidant Cemil Molla (1864–1941), who sometimes served as imam there, and just past the yalı waterside residence of Sare Hanım (1914–2000), aunt of left-wing poet Nâzım Hikmet (see

It’s taken me all this time to visit the bijou rectangular wooden mosque further up the coast towards the bridge—just below the mansion of Sultan Abdülhamid’s cultured confidant Cemil Molla (1864–1941), who sometimes served as imam there, and just past the yalı waterside residence of Sare Hanım (1914–2000), aunt of left-wing poet Nâzım Hikmet (see

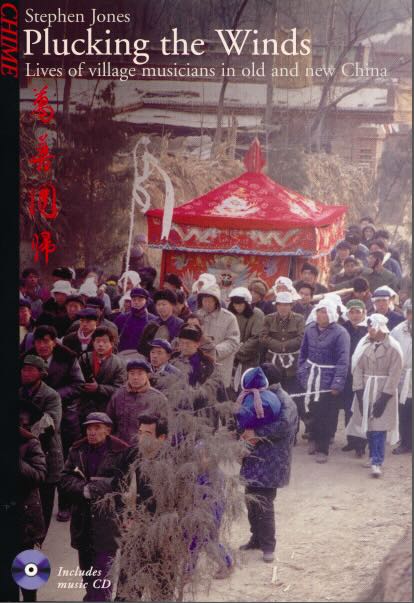

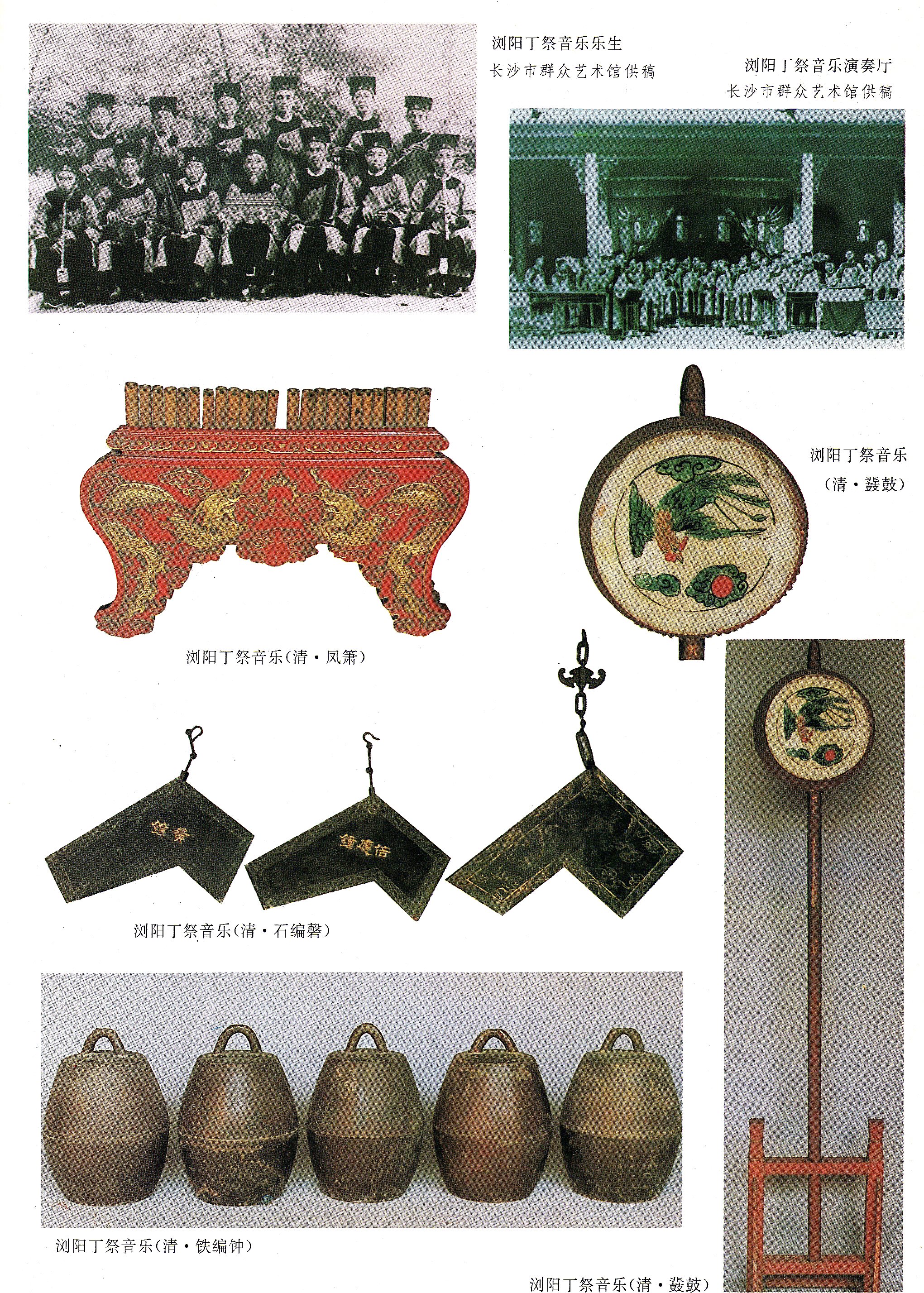

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

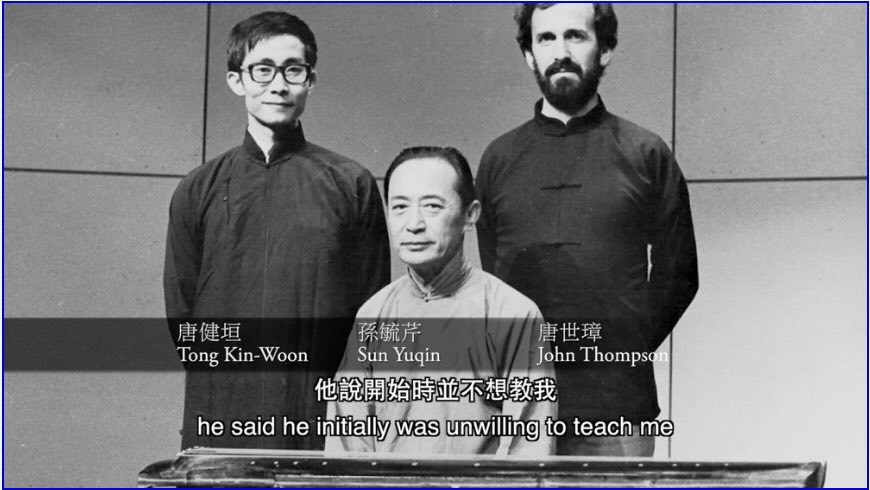

Shifan band, 1930s.

Shifan band, 1930s. Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).

Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).

Albanian zurna shawms with dauli drums, a

Albanian zurna shawms with dauli drums, a

Ukraine: Mykhailo Tafiychuk on volynka bagpipe of the Hutsuls.

Ukraine: Mykhailo Tafiychuk on volynka bagpipe of the Hutsuls.

Some association members.

Some association members.

“People were in and out of each other’s houses from dawn until bedtime.”

“People were in and out of each other’s houses from dawn until bedtime.”

The Shanhua temple during the

The Shanhua temple during the

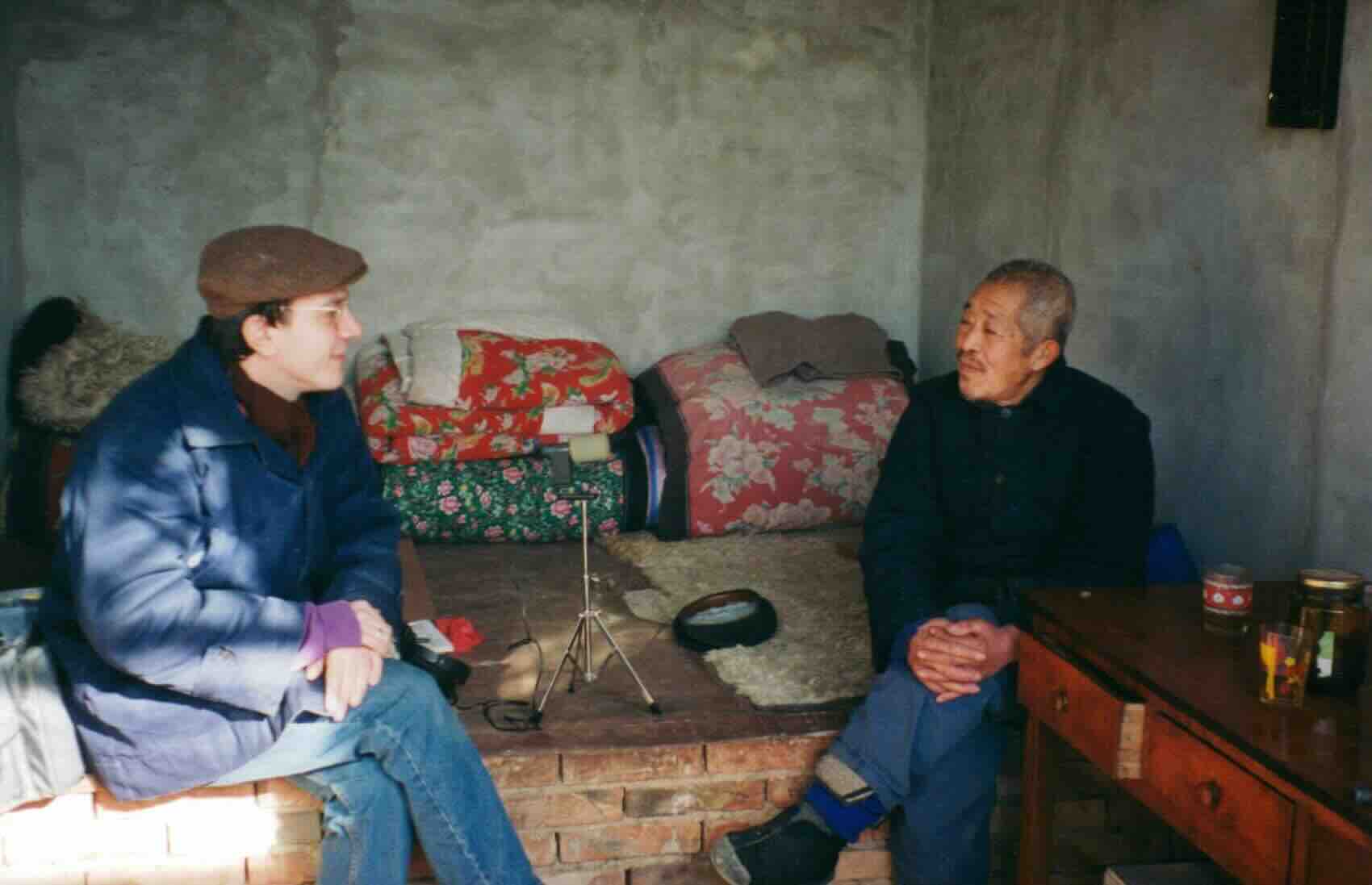

With Qiao Jianzhong (right) and Huang Xiangpeng, MRI 1989.

With Qiao Jianzhong (right) and Huang Xiangpeng, MRI 1989.

Qiao Jianzhong (left) and Lin Zhongshu (2nd left), 2013,

Qiao Jianzhong (left) and Lin Zhongshu (2nd left), 2013,

With Li Manshan and his Daoist band at the Gallerie, Milan 2012.

With Li Manshan and his Daoist band at the Gallerie, Milan 2012.

Lost Armenian monastery of Surp Asdvadzadzin at Tomarza,

Lost Armenian monastery of Surp Asdvadzadzin at Tomarza,

My photo.

My photo.

Mansur is passionate about the importance of music as a powerful tool for affecting change. Through his concept “The Laboratory of Democracy” (an open rehearsal session) Mansur engages both orchestras and audiences in issues such as co-existence, different levels of leadership, the nature of authority, of individual and collective responsibility as well as the difference between hearing and listening, leading and following. The sessions explore the basic concepts of democracy: individual worth, majority rule with minority rights, compromise, personal freedom and equality before the law, all demonstrated through the model of the orchestra as a miniature society. Mansur’s work on the peace-building role of music has also found expression of his conducting of the Greek/Turkish and Armenian/Turkish [youth] orchestras over several years.

Mansur is passionate about the importance of music as a powerful tool for affecting change. Through his concept “The Laboratory of Democracy” (an open rehearsal session) Mansur engages both orchestras and audiences in issues such as co-existence, different levels of leadership, the nature of authority, of individual and collective responsibility as well as the difference between hearing and listening, leading and following. The sessions explore the basic concepts of democracy: individual worth, majority rule with minority rights, compromise, personal freedom and equality before the law, all demonstrated through the model of the orchestra as a miniature society. Mansur’s work on the peace-building role of music has also found expression of his conducting of the Greek/Turkish and Armenian/Turkish [youth] orchestras over several years.

Éva Gauthier, 1905. All images from

Éva Gauthier, 1905. All images from

Sabahattin Ali (left) with Nazım Hikmet.

Sabahattin Ali (left) with Nazım Hikmet.

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual:

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual: The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

From The hundred thousand fools of God.

From The hundred thousand fools of God.