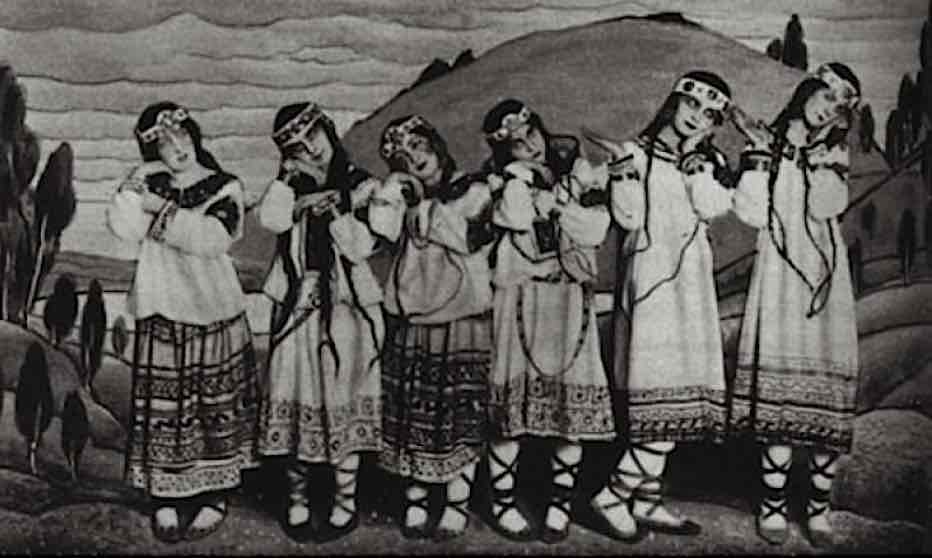

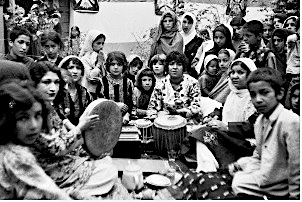

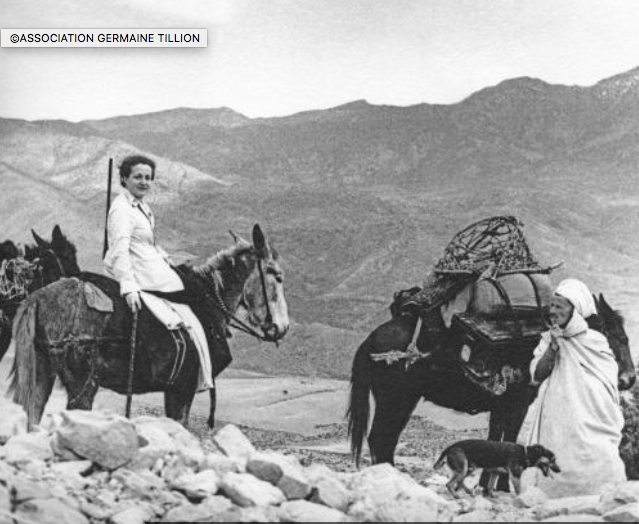

Esperance dancers. Source: EFDSS, via https://frootsmag.com/hoyden-morris.

Why bother traipsing halfway around the world, I hear you ask, when our very own Sceptered Isle offers such potential for pursuing the local ethnography of seasonal ritual?

Our folk culture may be a rich and ever-evolving topic, but Morris dancing has long been a national joke. Here I’ve churlishly suggested it as a suitably disturbing English riposte to the magnificent All-Black haka. I suddenly understand why some Chinese people may initially be reluctant to engage with their folk culture (see e.g. here and here).

Morris dancing comes round every so often as a drôle topic for media coverage—this article by A.A. Gill may not impress academics, but it’s brilliant, evocative, and strangely respectful writing.

I’m reminded of the topic again by a recent BBC4 programme, engagingly titled For folk’s sake.

One could almost mistake the May procession, with its bowery palanquin,

for a rain ritual in Shaanbei.

Now, I take a keen interest in calendrical rituals—indeed, as Easter week approaches, Bach is in store, and it’s a busy season for ritual in China too. But I’m not alone in tending to consign Morris dancing, with its incongruous juxtaposition of hankies, bells, and silly hats with beards and beer, to a long list of embarrassing genteel eccentricities of the English, along with The Archers. But like any social activity performed by Real People it deserves serious study, in the context of social change in England since the Industrial Revolution, and even a preliminary exploration is fascinating. [1]

The wiki entry makes a useful starting point. Whatever the etymological connection between Morris and Moorish, it does seem, Like Life (cf. Stewart Lee), to have come from abroad. It’s part of a group of genres that includes mummers’ plays, sword and stick dances, and so on.

Gender and class

Though there is evidence of female Morris dancers as early as the 16th century, male groups predominated. I’d like to learn more about the 19th-century decline; anyway, by the early 20th century the women who soon became the driving force of Morris learned from surviving male performers. From wiki:

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Lancashire tradition was taken up by sides associated with mills and nonconformist chapels, usually composed of young girls. These lasted until the First World War, after which many mutated into “jazz dancers” [note the cryptic quotes].

After severe losses in World War One (when some entire village sides were killed) the female dominance increased, with women now teaching men.

After severe losses in World War One (when some entire village sides were killed) the female dominance increased, with women now teaching men.

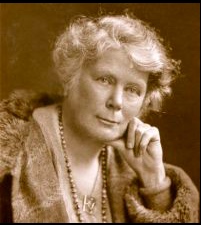

In 1895 Mary Neal (1860–1944; website here; see also Lucy Neal’s project and this nice article) founded the Espérance Club, a dressmaking co-operative and club to enrich the lives of young working-class girls in London:

No words can express the passionate longing which I have to bring some of the beautiful things of life within easy reach of the girls who earn their living by the sweat of their brow… If these Clubs are up to the ideal which we have in view, they will be living schools for working women, who will be instrumental in the near future, in altering the conditions of the class they represent.

Cecil Sharp (1859–1924) first experienced Morris at Headington Quarry in 1899. Mary Neal began working with him in 1905, but their outlooks conflicted, and she soon joined the WSPU (for the Espérance’s modern reincarnation, see here). Vic Gammon encapsulates the conflict in his review of Georgina Boyes’s The imagined village culture:

Mary Neal, middle-class reformer, socialist, and suffragette who sees the possibility of reviving folk dance among working-class girls in north London, is defeated by Cecil Sharp, professional musician, Fabian, and misogynist who spread the activity of folk dancing among the young genteel, making vernacular arts fit bourgeois aesthetics.

These clips from 1912 feature the sisters Maud and Helen Karpeles, co-founders of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, as well as Cecil Sharp, and George Butterworth, who died in the Battle of the Somme:

But as in the world of work, male groups soon came to dominate again. The all-male Morris Ring was founded by six revival sides in 1934. And between the wars, for John Eliot Gardiner’s father Rolf “mysticism, misogyny, and Morris dancing formed a coherent whole in which nostalgia was a spur to action”. Whether he would have approved of The Haunted Pencil, with his AfD comrades, I couldn’t possibly comment.

Meanwhile Stella Gibbons and Elisabeth Lutyens took a more cynical view of genteel “folky-wolky” representations of English folk culture (note also Em creeps in with a pie).

Following World War Two, and particularly in the 1960s, there was an explosion of new dance teams, with some women’s or mixed sides. A heated debate emerged over the propriety and even legitimacy of women dancing the Morris; and mainly on the left, critics disputed the method of Sharp’s work as they pondered the perilous concept of “tradition” (as they do). But as in most walks of life, despite bastions of male conservatism, the creative participation of women is again becoming a major driving force, as you can see in this fine article by Elizabeth Kinder.

Click here for a short clip from Berkhamstead in 1950, with pipe and tabor sadly mute. And this was filmed in Thaxted (“hub of the universe”), c1958—just as collectivization was leading to calamitous famine in China:

All this may seem quaint at any period, but all the more so in the Swinging Sixties. For folk’s sake shows glimpses of a 1966 festival at Thaxted—just as revolution (not least the Cultural Revolution) was in the air, alongside jazz, soul, the Beatles… The Saddleworth rushcart festival features in For folk’s sake—here’s a clip from 2014:

And as with folk traditions in China and worldwide, Morris survives alongside newer genres like punk (for punk in Beijing, see here).

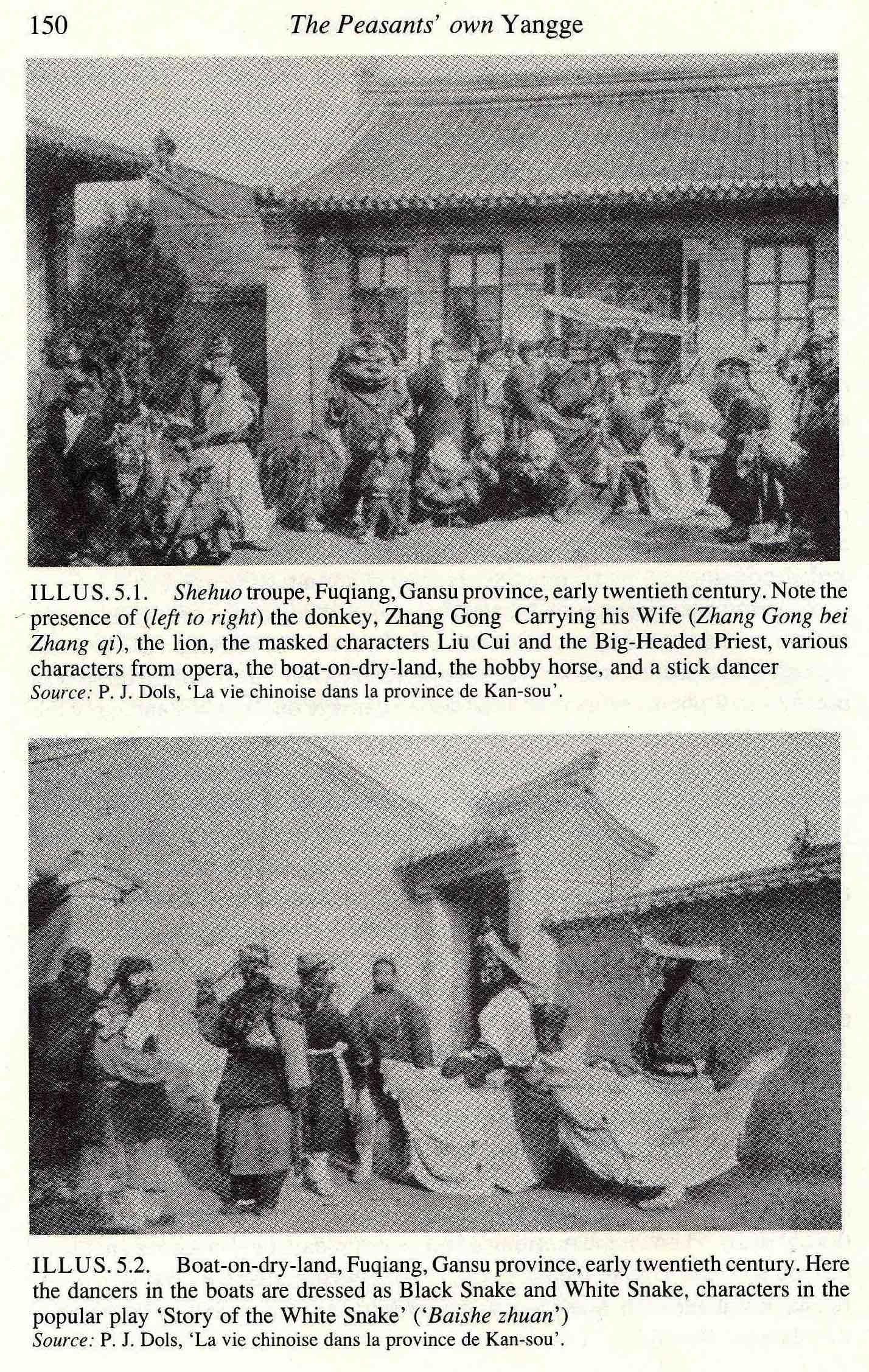

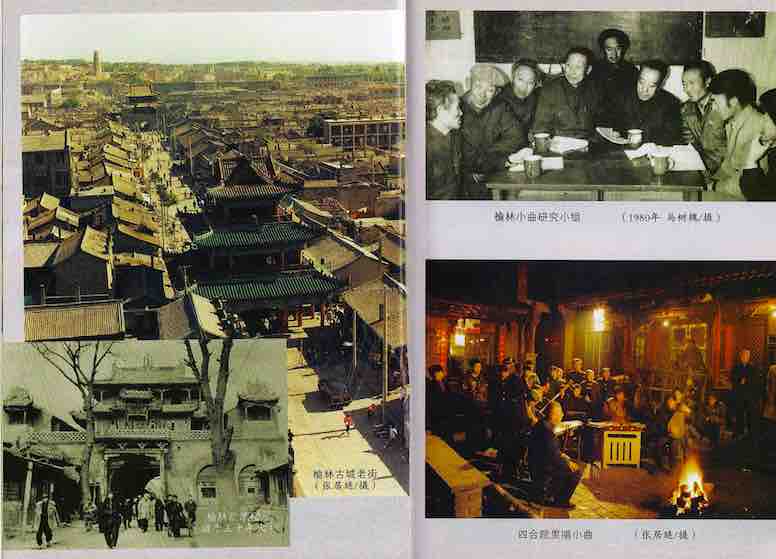

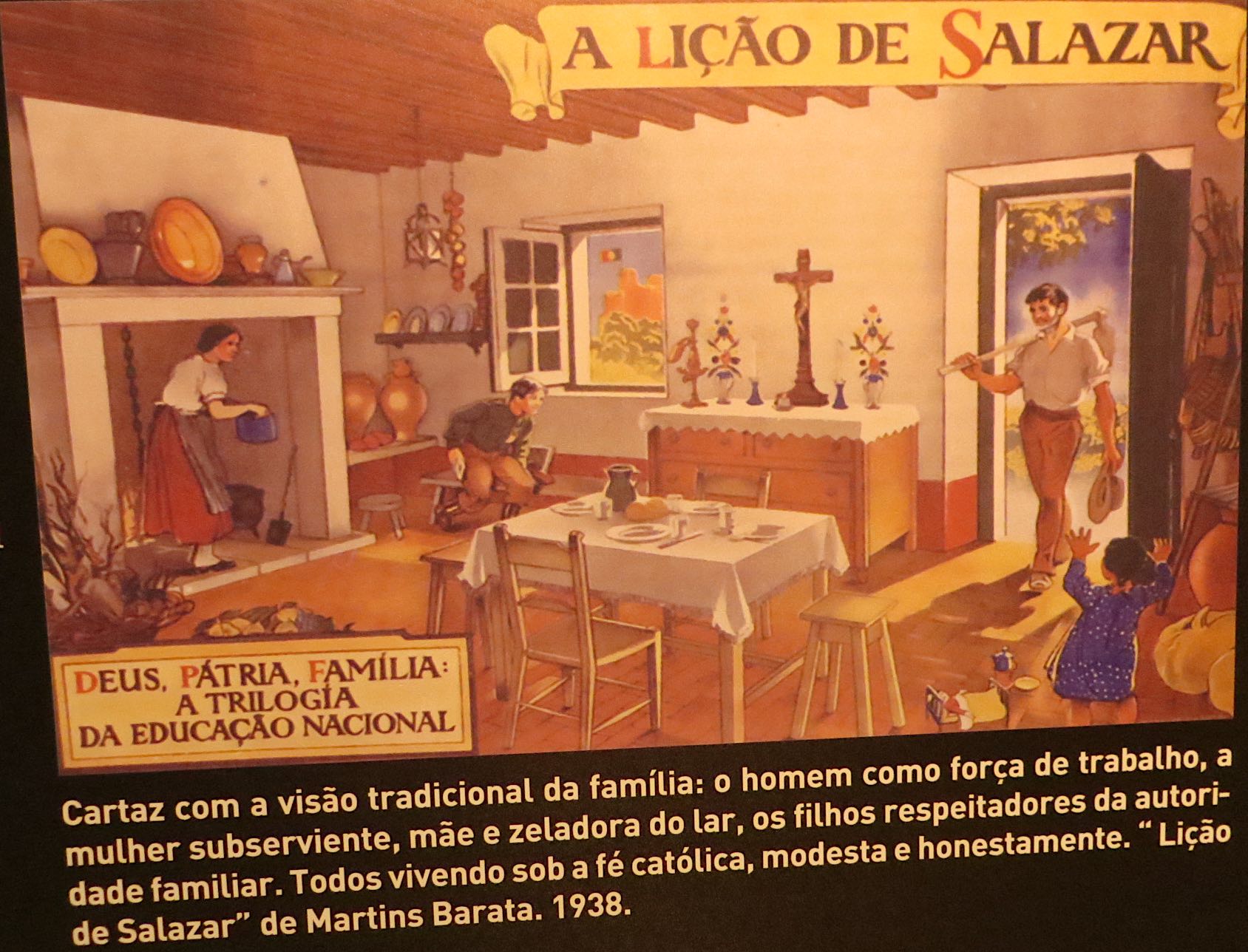

Source: David Holm, Art and ideology in revolutionary China (1991).

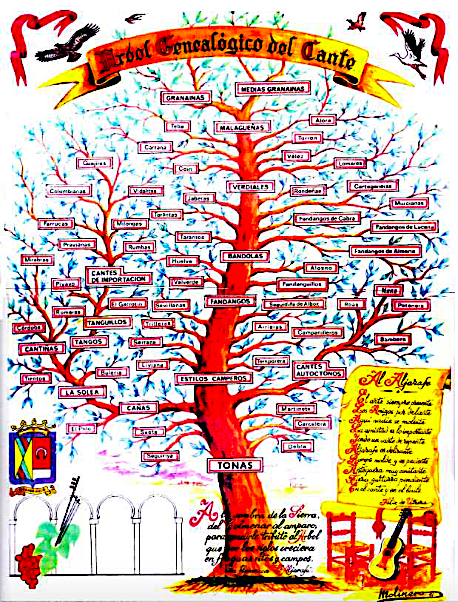

Indeed, a survey of the many English villages with teams somewhat resembles our documentation of ritual groups in particular counties of China—or the rich local dance traditions like yangge (among several genres using handkerchiefs and sticks!), Boat on Dry Land, Bamboo Horses, and so on, with their common ritual connections—covered at length in the provincial volumes of the Anthology for dance:

- Zhongguo minjian wudao jicheng 中国民间舞蹈集成,

with over 30,000 pages there alone, besides all the related material in the volumes for folk-song, narrative-singing, opera, and instrumental music.

Among the main regional Morris traditions are Cotswold, Northwest, Border, and Plough Monday groups in Yorkshire and the east Midlands (all the sides have instructive websites)—and as in China, their styles are often distinctive to individual villages. Four teams claim a continuous tradition predating the revival: Abingdon, Bampton, Headington Quarry, and Chipping Campden. In the 1930s at the important centre of Thaxted, the sinologist Joseph Needham championed Molly dancing.

Only now do I recall that my granddad took me to watch mummers in Wiltshire (at Colerne? Marshfield?). Indeed, his home village of Potterne still has a group. It’s a very blurred childhood memory, by which I seem to have been underwhelmed; but did it sow a seed?

The Britannia Coco-nut [2] Dancers of Bacup (“Nutters”; see e.g. this article) have a venerable history that inevitably attracts controversy (no less inevitably, one of the transmitters is called Dick Shufflebottom, who celebrated fifty years of service in 2006). A.A. Gill’s description of the Nutters is classic:

They are small, nervous men. And so they might be, for they are wearing white cotton night bonnets of the sort sported by Victorian maids, decorated with sparse ribbons. Then black polo-neck sweaters, like the Milk Tray man, with a white sash, black knee-breeches, white stockings and black clogs. As if this weren’t enough, someone at some point has said: “What this outfit really needs is a red-and-white-hooped miniskirt.” “Are you sure?” the dancers must have replied. And he was. But it doesn’t finish there. They have black faces, out of which their little bright eyes shine anxiously. On their hands are strapped single castanets. A single castanet is the definition of uselessness. The corresponding castanet is worn on the knee. To say you couldn’t make up the Coco-nutters would be to deny the evidence of your astonished eyes.

The dance begins with each Nutter cocking a hand to his ear to listen to something we human folk can’t catch. They then wag a finger at each other, and they’re off, stamping and circling, occasionally holding bent wands covered with red, white, and blue rosettes that they weave into simple patterns. It’s not pretty and it’s not clever. It is, simply, awe-inspiringly, astonishingly other. Morris men from southern troupes come and watch in slack-jawed silence. Nothing in the civilised world is quite as elementally bizarre and awkwardly compelling as the Coco-nutters of Bacup. What are they for? What were they thinking of? Why do they do these strange, misbegotten, dark little incantations? It’s said that they might have originally been Barbary corsairs who worked in Cornish tin mines and travelled to Lancashire, and that the dance is about listening underground, a sign language of miners. And then there’s all the usual guff about harvest and spring and fecundity, but that doesn’t begin to describe the strangeness of this troupe from the nether folk world.

Do watch the Nutters on YouTube.

Again as in China, the Morris vocabulary is suggestive, with teams, sides, squires, bagmen, fools, beasts. At least England hasn’t yet fallen for the Intangible Cultural Heritage flapdoodle (we have our pride). Still, even without it, contentious arguments about “authenticity” continue to fester. And even now there’s still considerable opposition to admitting women. FFS.

I might be tempted to make the music share the blame. Of course, it is what it is, irrespective of the impertinent tastes of outsiders; but it often seems to endow the proceedings with a twee comfy feel that conflicts with the edgy (“pagan”?!) atmosphere of the dance itself. Once mainly accompanied by pipe and tabor, fiddles and melodeons became more common. The gritty new sounds of great musos like Jon Boden don’t seem so relevant to most Morris sides—though again, see Elizabeth Kinder’s article. I’d love to hear a Bulgarian version—accompanied with suitably complex metres by zurna and davul, relatives of early English pipe and tabor.

For the BBC2 documentary Tribes, predators and me, it was a cute idea to show footage of Morris dancing to tribespeople (click here).

* * *

Of course I’m merely dabbling here. But is this the kind of thing that urban educated Chinese people think I’m doing in their country?

In a way, it is: cultures change, in China as in England. The brief of the ethnographer is the same: to document the whole history, down to today, of local traditions amidst ongoing challenges to community cohesion through social and political change. We both have blind spots about our own cultures, further muddied by patriotic posturing and our reactions against it. It’s not that I can’t see the “value” of Morris, just that I’ve inherited negative associations. While plenty of English writers have debunked the myth of an unspoilt Victorian Merrie England, in China the “living fossils” nostalgia, referring to a Golden Age of much greater antiquity that bears even less relation to rural life there, is still touted by heritage pundits. For the awful cliché of “international cultural exchange”, see here.

And whereas in China I’m keenly aware of major dates in the rural calendar when temple fairs may be held, I’m not alone in being completely estranged from the seasonal rhythms of English life; only Bach cantatas manage to educate me.

This may be a particular issue for the English. In Hungary the táncház revival has become popular; and it would seem natural enough for an American studying old-time music in Appalachia to find continuity when working on China.

The world of Morris and English folk-song culture, like that of Newcastle punks, is no more “home” to me than are the rituals of the Fujian countryside for an educated Chinese from Beijing. But whereas local ritual in China still seems to me an intrinsic component of local life, Morris dancing has long seemed a quaint byway in my whole experience of England. Of course, when pressed, I can quite see this is wrong. OK Guys, I’ll take my culture seriously if you take yours…

Anyway, just think, as you board a rickety bus to a poor Hunan village in search of household Daoist rituals, you could be sitting in a sunny Oxfordshire pub courtyard nursing your pint as you take notes on the magnificent ritual spectacle unfolding before you—complete with its “feudal superstitious colourings” 封建迷信色彩.

See also my haiku on Morris dancing. Click here for English folk-song; and for posts on Irish music, here. For a roundup of posts on the English at home and abroad, see here; and for more on Heritage movements, here.

[1] Useful background includes the research of Vic Gammon; Georgina Boyes, The imagined village culture: culture, ideology and the English folk revival (1993/2010); Trish Winter and Simon Keegan-Phipps, Performing Englishness: identity and politics in a contemporary folk resurgence (2013); numerous publications from the English Folk Dance and Song Society, e.g. here; Theresa Buckland, ” ‘Th’owd pagan dance’: ritual, enchantment, and an enduring intellectual paradigm” (2002). On class, gender, and national identity, see also this (cf. Stewart Lee!). For innovative performance-based studies of clog dancing, see the work of Caroline Radcliffe. For an accessible introduction to the English folk scene, see The Rough Guide to world music: Europe, Asia, and Pacific, “England: folk, roots”, and regular features in Songlines and fRoots.

For further refs. on the wider context, see Helen Myers, “Great Britain”, in Ethnomusicology: historical and regional studies (The New Grove handbooks in music, 1993), pp.129–48. Among many fine compilations of British folk music, note the extensive Topic Records series The voice of the people (here on Spotify).

[2] Pedants’ corner (or is it Pedant’s corner?): the form “coconut” seems more common (as on their own website)—I can’t find a ruling on the hyphen, but it seems suitably eccentric (but was it eccentric then? That’s the perennial question!).

Glorious is the Earth

Glorious is the Earth