I learned a lot from my invaluable fieldwork companions Xue Yibing 薛艺兵 and Zhang Zhentao 张振涛. Within Zhang’s prolific output, his book on the Hebei ritual associations is outstanding (see e.g. here). He has just published a perceptive review of my recent film Seated at the altar, based on his own rapport with the Gaoluo villagers:

- “Guying yu duju—Zhong Sidi jilupian ‘Zuotan: 1995 nian Nan Gaoluo cun yinyuehui zhengyue yishi’ yingping”, 孤映与独举——钟思第纪录片《坐坛:1995年南高洛村音乐会正月仪式》影评, Zhongguo yinyuexue 中国音乐学 2025.2.

No sooner had I surmised that Chinese audiences might not articulate the stark differences between my (inadvertently) ethnographic perspective and the sanitised, beautified portrayals from the Intangible Cultural Heritage (e.g. here; cf. Gaoluo film: a village screening), Zhang does precisely that.

The social context of Chinese folk musical cultures hardly appears on film. While I had blamed this on the ICH system since 2004, Zhang shows how deeply embedded is China’s history of romanticising and glamorising rural life. Despite Chinese scholars’ exposure to Western ethnography since the 1980s, his comments suggest that social realism has had little impact, and that the habit of self-censorship remains ingrained. I suppose the Party line is that while one may wish to film for one’s own research purposes, such scenes are not fit for public consumption: that we should draw a veil over poverty—over real life. In international visual anthropology the theoretical nuances of the film-maker’s “gaze” are much discussed, but this seems a particularly disturbing impasse.

Even Zhang Zhentao, who evokes village life in detail on the page, seems somewhat perplexed that we might want to display images of it. He finds the style of Seated at the altar consistent with that of my film on the Li family Daoists, and he might also have mentioned the DVDs with my two books on Ritual and music of north China. Playing devil’s advocate, he reiterates the simplistic notion that foreigners choose to depict China in ugly and shameful images, making the Chinese people “lose face”. He queries an apparent lack of “aesthetic” values (shenmei, where mei means “beauty”), adducing scenes from my films showing squalid streets and dwellings, shabby clothes, old women with bound feet, and the decaying architectural remnants of political campaigns. As he explains, such scenes are justified by the ethnographer’s search for “authenticity” and “realism”. *

To dispel China’s victim complex, it should suffice to watch documentaries filmed in India, Africa or Indonesia—and indeed on our own doorstep, such as De Martino’s films on taranta. But Zhang’s comments suggest that documentaries about other parts of the world have little influence in China.

As to fictionalised films, Zhang mentions the classic 1979 Abing biopic Erquan yingyue, as well as the movies of Zhang Yimou (and rather than the beautified images of Raise the red lantern, I much prefer the gritty realism of The story of Qiuju, or Jia Zhangke‘s depictions of small-town life). In between stand movies like Yellow earth or The old well (see here). While “underground” documentaries like those of Wang Bing, Ai Xiaoming, Hu Jie, and Jiang Nengjie, or the subaltern films of Xu Tong, boldly challenge the Party line, investigative Chinese TV documentaries show (or showed?) scenes of real village life, and brief unedited footage on Chinese websites and YouTube makes a useful resource. I wonder how Chinese audiences assess Sidney Gamble’s footage from 1920s’ Miaofengshan. Some non-Chinese scholars have issued documentaries on expressive and ritual culture in rural China, such as Chinese shadows, Bored in heaven, and the films of Jacques Pimpaneau (see this roundup). We might also adduce Ashiq: the last troubadour.

Politics: text and image

It’s impressive that Zhang Zhentao broaches the issue of gaze, but he can hardly spell out another respect in which my perspective differs. My films complement my written texts—which though full of detail on the successive social and political upheavals of the 20th century (notably the Maoist era), attract little attention in China because few of them are accessible in Chinese (though see here and here). Politics is the elephant in the room, remaining taboo for music scholars within China; and among Chinese anthropologists too, few go so far as Guo Yuhua in documenting the ordeals of villagers under Maoism (see also here).

Text allows for more detail; film makes a more vivid impact. Whereas the film could only hint at the impact of political campaigns on ritual life in Gaoluo, in my book Plucking the winds I discussed this in some depth—such as the devastating national famine of 1959–61, of which very few images are available, by contrast with propaganda films on the supposed achievements of the Great Leap Forward.

Filming ritual and expressive culture

In China, besides the official taboos on showing poverty and discussing politics, the study of religious ritual is largely confined to textual studies of pre-modern history.

Before the ICH (even during the Anthology era of the 1980s–90s), Chinese fieldworkers rarely had the wherewithal to film ritual activity; and even if they did so, such footage could hardly be published. I too filmed merely for my own research purposes, to enable me to document ritual activity in far greater detail than I could achieve through making notes, taking photos, and recording audio; my footage included all too few scenes of daily life, which significantly enhance a film.

Shaanbei: scenes from Notes from the yellow earth.

My own films include scenes of lowly shawm bands at village funerals, a blind bard performing for a family blessing, beggars singing at a wedding, and a drunken folk-singing session in a poor peasant home. There is nothing sensationalist or demeaning about all this. If we seek to document rural Chinese communities and their expressive culture, how can we then ignore the conditions in which it takes place? Even if I could think how to sanitise, beautify, and idealise such scenes, it would never occur to me to do so. The social and historical setting matters, but is airbrushed in China. While I see the differences between my approach and that of the ICH, I have no intention of being controversial: I merely seek to document traditional ritual culture as best I can.

Gaoluo: ritual, “music”, and daily life

In filming the New Year’s rituals in Gaoluo, my choices were limited, largely consisting not of any grand conceptual vision but of finding physical positions from which to frame the scene.

Knowing these villages so well, Zhang Zhentao seems both impressed and disturbed by my vignettes of daily life there—elderly people relaxing in the sunshine, Cai An at his general store, the family eating dumplings. Wearing their everyday clothes, villagers perform in simple peasant houses decorated only by pinups, or before the god paintings in their humble ritual buildings, with cigarette cartons and thermos flasks placed besides instruments on rickety wooden trestles—by contrast with the ICH format of presenting folk groups in fake-antique costumes performing on the concert stage or in tidy, arid government courtyards. Villagers smoke, they joke; they ride motor-bikes and use mobile phones. Social context is important; to censor the conditions of village life would be mendacious. It should go without saying that my films are made with the utmost respect for my village hosts, serving as a tribute to their resilience. **

“Music”

Zhang Zhentao stresses the contributions that musicologists can make to ethnographic filming, but for me the challenge is the other way round. In reviewing Seated at the altar he focuses on the recitation of “precious scrolls” and the moving performance of the percussion suite—but I see these as inevitable components of documenting the entire ritual process. What I find significant is including scenes that may appeal more to ethnographers than to musicologists, such as (in Li Manshan) choosing the date and siting of the burial, the encoffinment, and informal scenes of the Daoists relaxing between rituals; or (in Seated at the altar) worshippers kowtowing and offering incense, or preparing the soul tablet for the deceased.

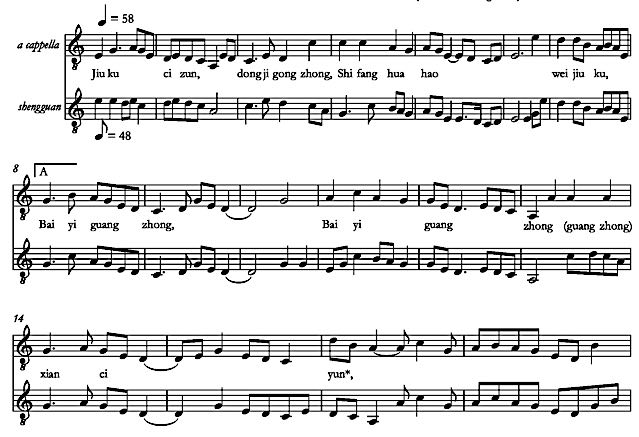

Zhang highlights the vocal liturgists’ renditions of the Houtu precious scroll before the gods in the lantern tent. Here he does well to observe that they had only been striving to recreate it in performance since 1993, at our behest; their efforts were less than ideal, and the future of the vocal liturgy still remains precarious. The recitation of the precious scrolls is most distinctive, but to me, just as crucial are the scenes that show their singing of the hymns that punctuate funerals and the New Year rituals, including The Incantation of Pu’an.

Similarly, while Zhang pays tribute to the visceral affective power of the percussion suite, I would also draw attention to the shorter percussion pieces that punctuate rituals. Still, the suite intoxicated me so much that over the years I missed no opportunity to film it during rituals, which taught me to find a suitable position and to zoom and pan at meaningful places. In China it would be unlikely to show the percussion suite within its actual function of ritual performance, but surely even Chinese audiences will find the result beautiful. True, in the Appendix that follows the final credits, our experiment with Cai An and Cai Yurun demonstrating the sections was one that might occur only to musicologists. ***

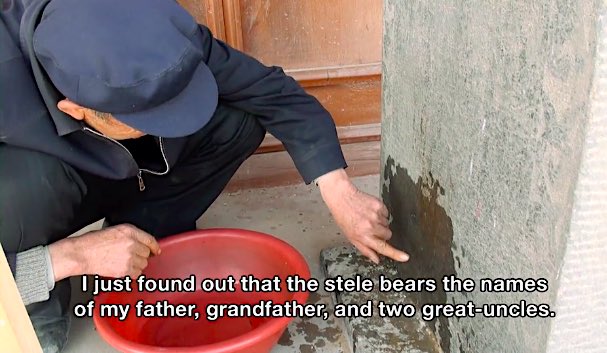

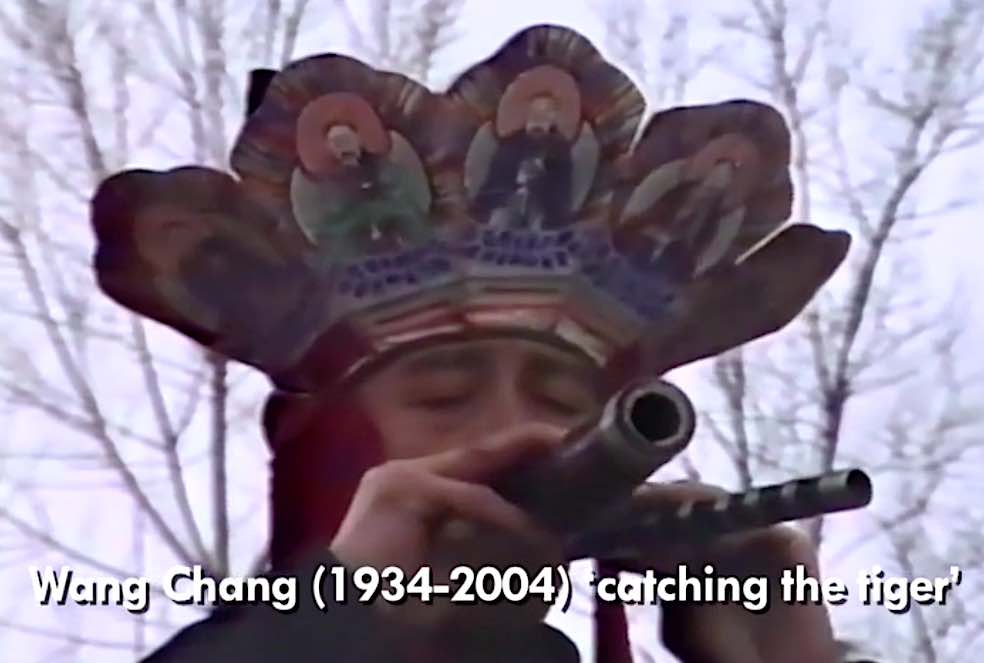

As to those final credits, Zhang notes the poignancy of the long list of performers, with their dates—many of them having died since the footage was filmed.

* * *

In sum, I simply fail to see how to evoke village ritual life, in either text or images, without providing social and historical context. Yet basic anthropological principles, that to us are self-evident, appear to struggle to gain acceptance in China—all the more under the current ICH regime. Because I’m so impressed by the work of my Chinese colleagues, I sometimes fail to register the constraints under which they operate.

Meanwhile at the Shanghai Centre for Ritual Music, Xiao Mei offers an impressive training in international approaches to ethnographic film-making, making me keen to see how they bridge the gulf—see my further reflections after my film won awards at the 4th Chinese Music Ethnographic Film Festival in Shanghai this July.

* And what if villagers actively prefer to be displayed in glamorous costumes on the concert stage?! So far I have no evidence that they are so allergic to displaying the conditions of their lives as are apparatchiks.

** Partly because I was reminded of the sad decline of revolutionary hero and vocal liturgist Cai Fuxiang, in the film’s funeral scene I included one tiny shot of the village’s only beggar at the time. I regret not chatting with him, because he would have added to our picture of village life, and our visit might have enhanced his self-esteem.

Cf. my sketch of the affable disabled ritual helper Yanjun in Yanggao, whose story I only gleaned at second hand (see under Yanggao: personalities).

In the film I allude to the Catholic minority in Gaoluo since the late 19th century, the 1900 massacre, and their re-evangelisation by Italian priests from the 1920s. Their continuing activity is a sensitive subject, but the scene of their brass band parading at New Year 1995 was so striking that it seemed acceptable to include it.

*** Cf. the complete shawm suite (with useful musical signposts in the voiceovers) at a 1992 funeral that forms the Appendix of my 2007 DVD Doing things.

The Li family Daoists perform the

The Li family Daoists perform the  Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

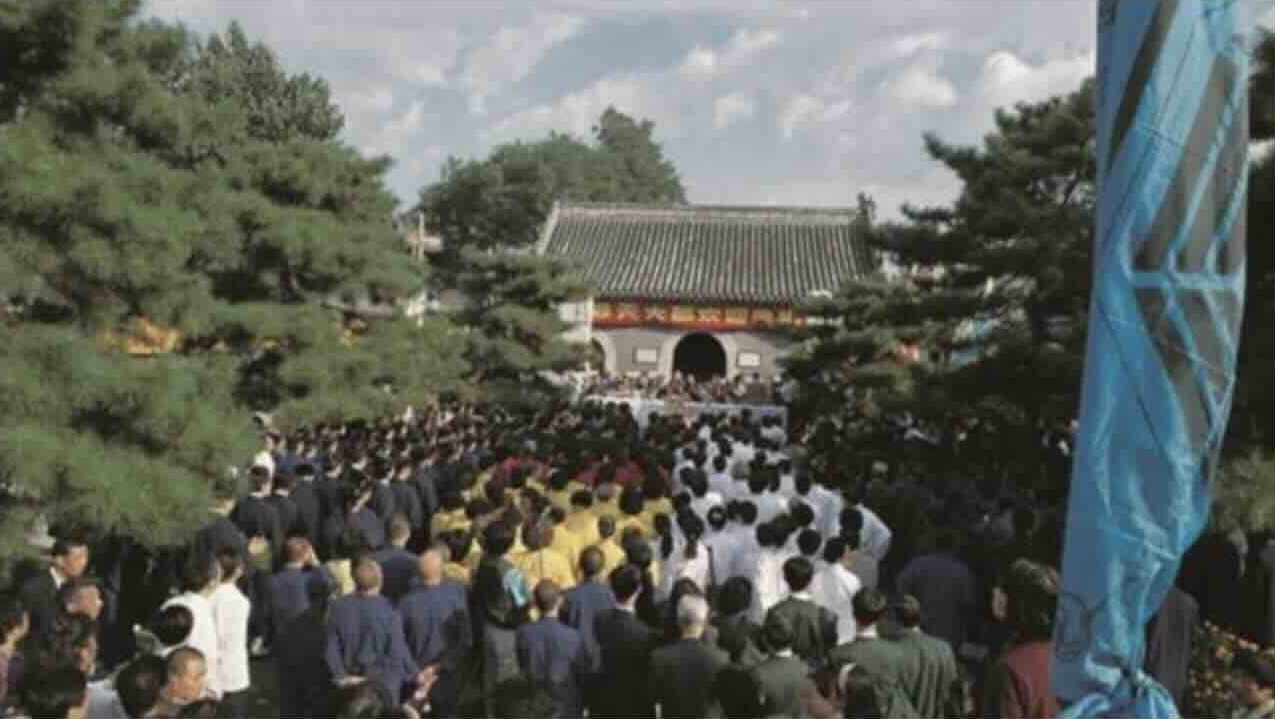

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

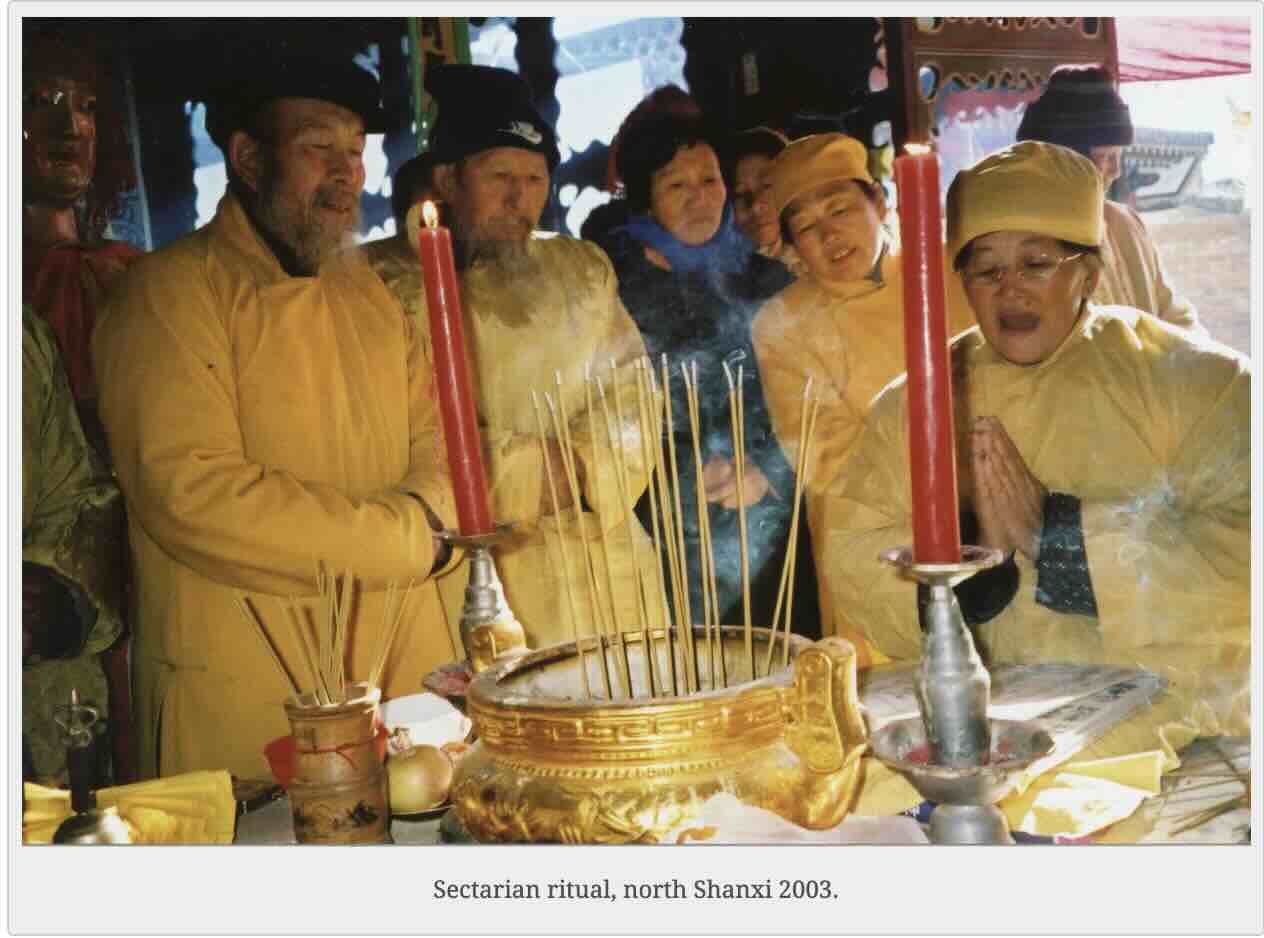

Ghost King,

Ghost King,  Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,

The Shanhua temple during the

The Shanhua temple during the

With Li Manshan and his Daoist band at the Gallerie, Milan 2012.

With Li Manshan and his Daoist band at the Gallerie, Milan 2012.

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual:

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual: The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

For both folk and art music in the time of Vermeer, click

For both folk and art music in the time of Vermeer, click

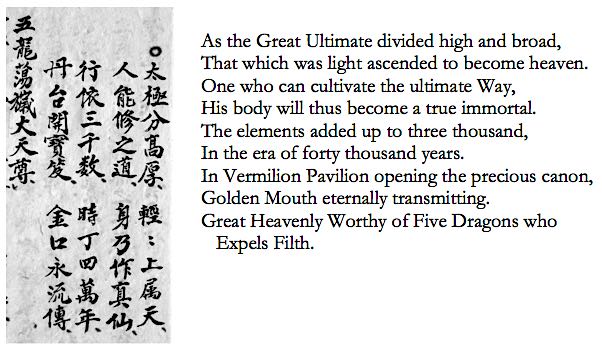

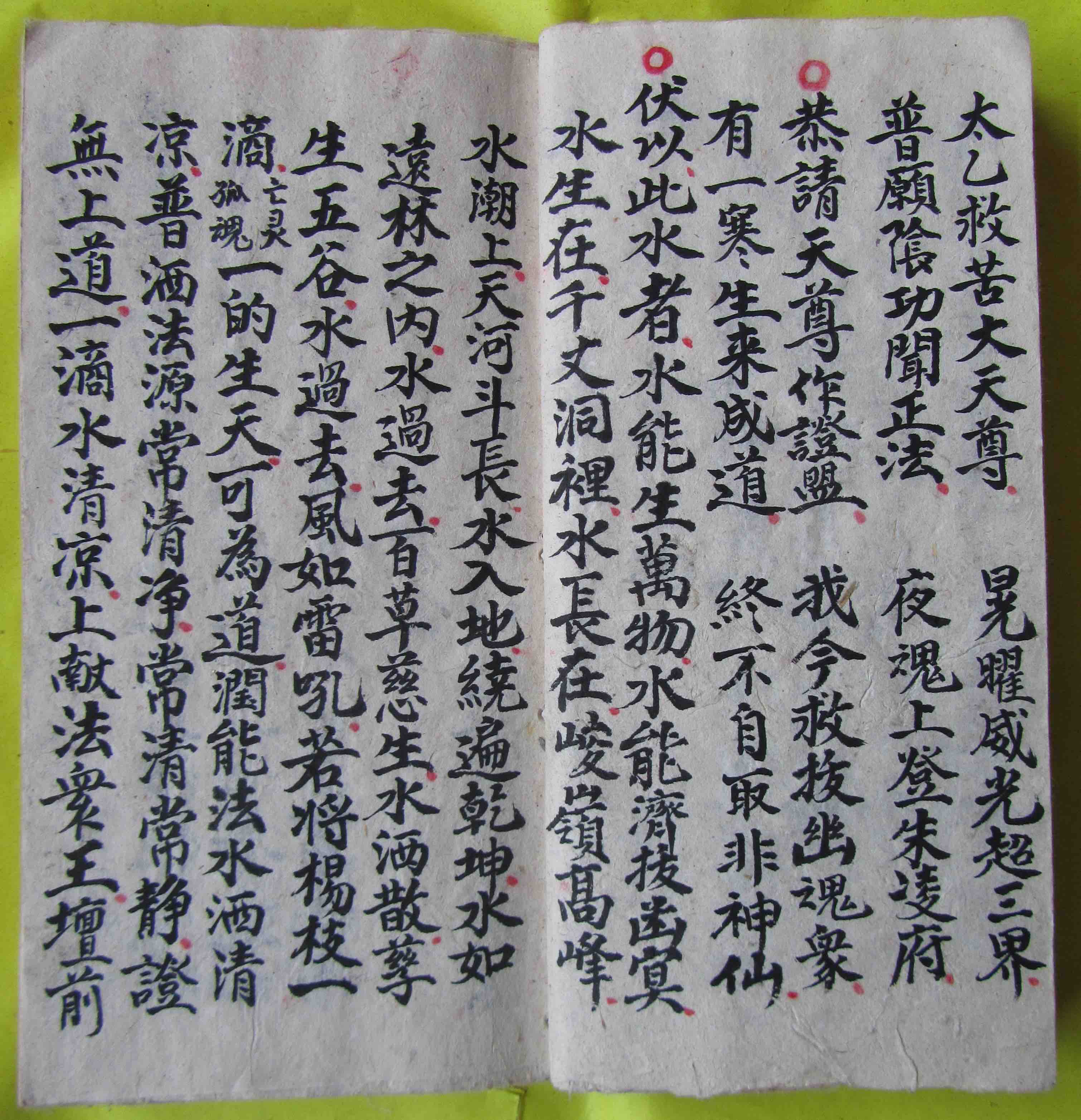

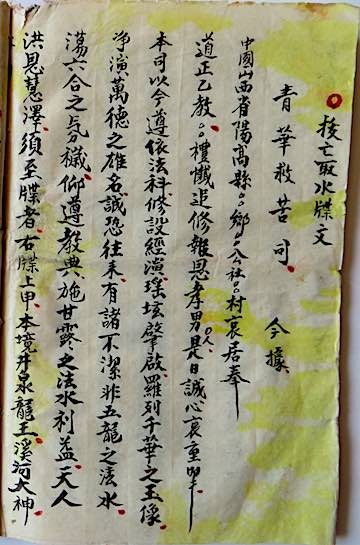

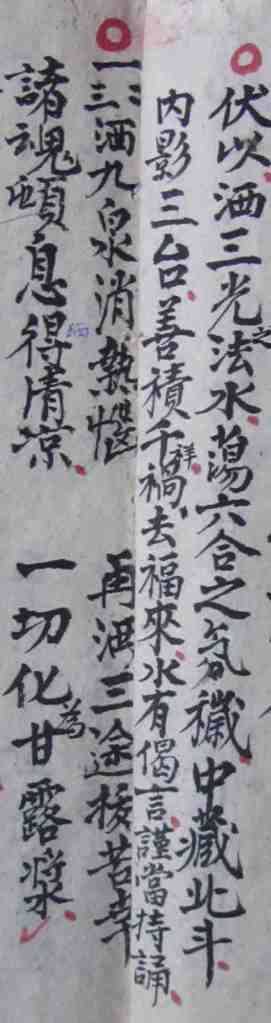

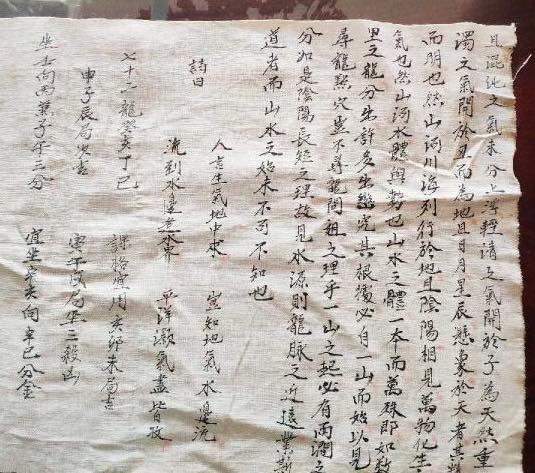

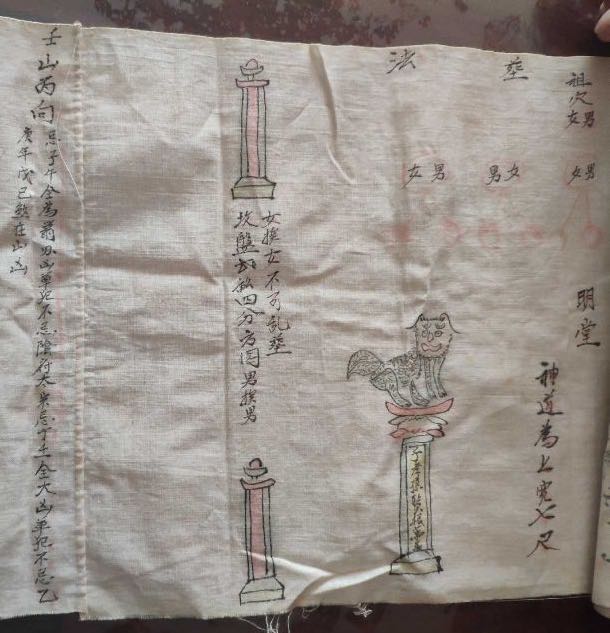

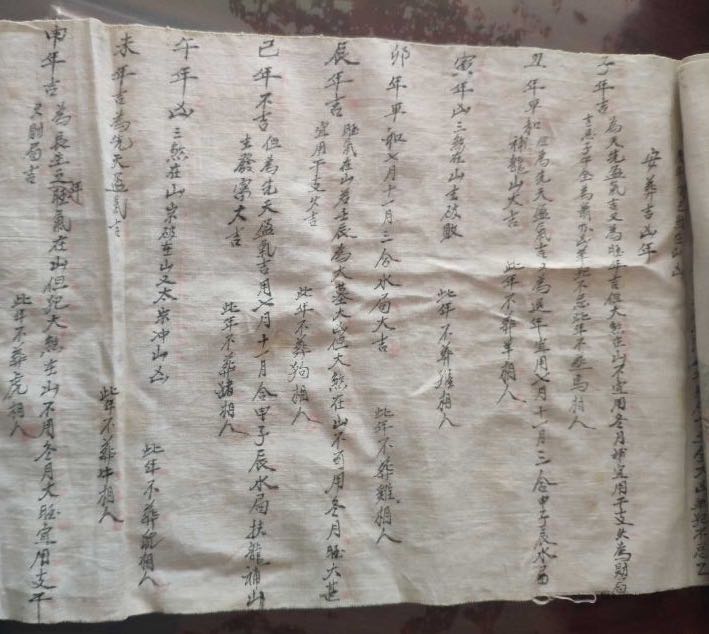

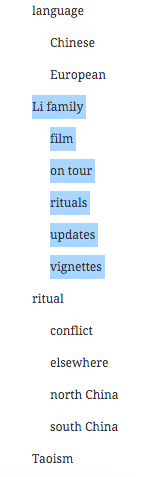

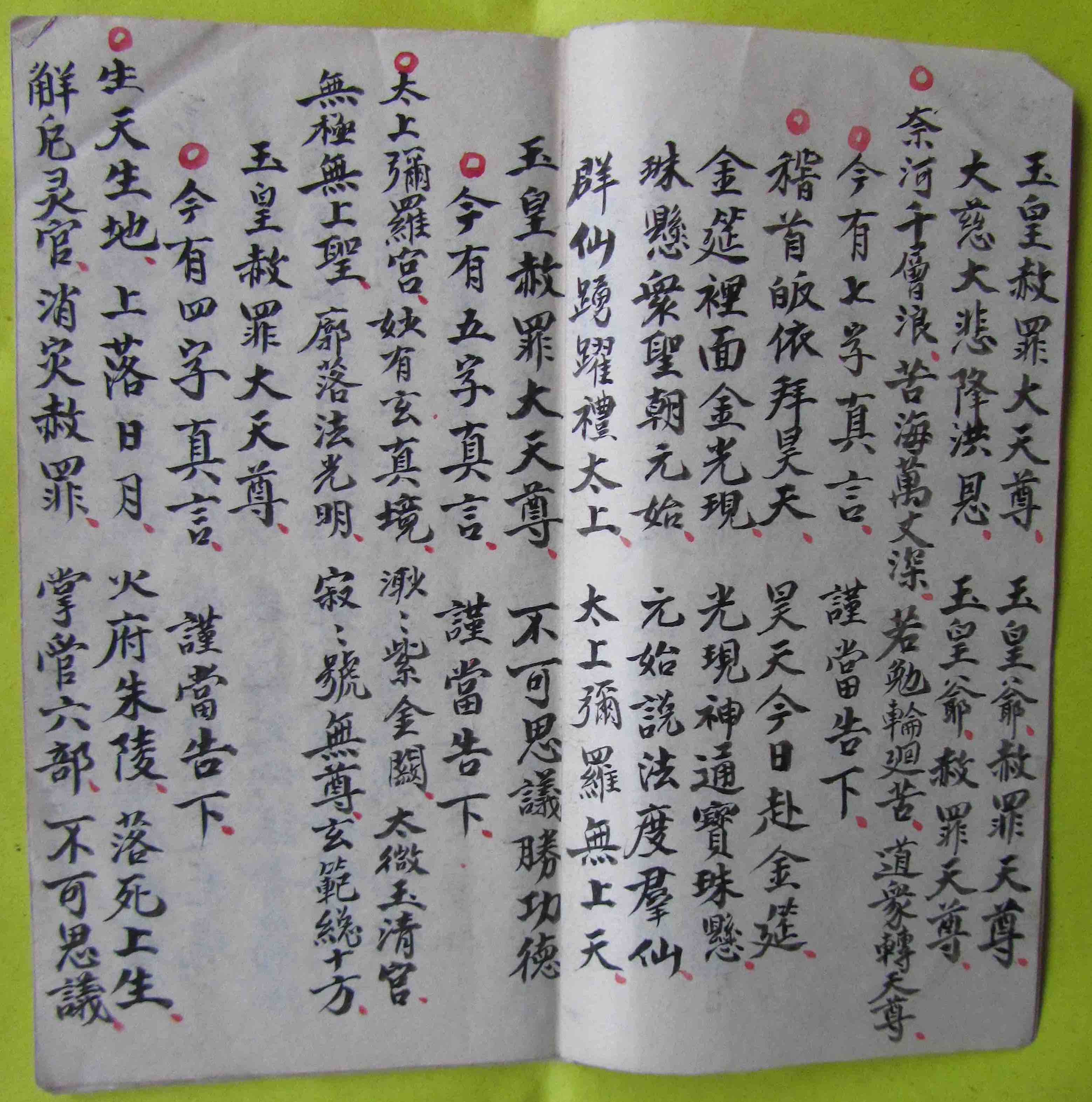

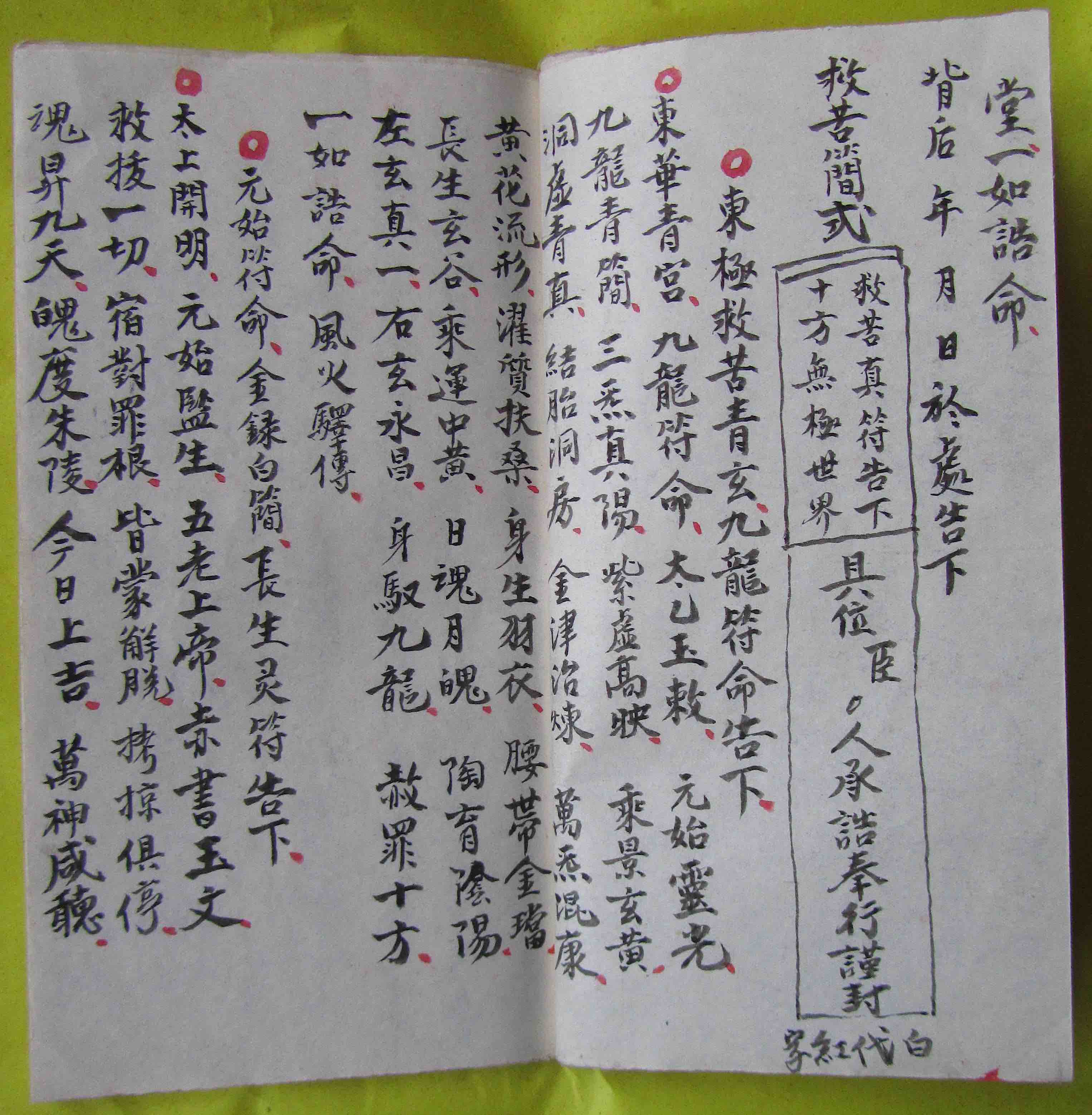

Lingbao kaifang shezhao yubao xianzhuan youlian poyu fangshe duqiao zhu baiyu rang huangwen [ke] 靈寶開放[方]攝召 預報獻饌遊蓮破獄放赦渡橋祝白雨禳蝗瘟[科]

Lingbao kaifang shezhao yubao xianzhuan youlian poyu fangshe duqiao zhu baiyu rang huangwen [ke] 靈寶開放[方]攝召 預報獻饌遊蓮破獄放赦渡橋祝白雨禳蝗瘟[科]

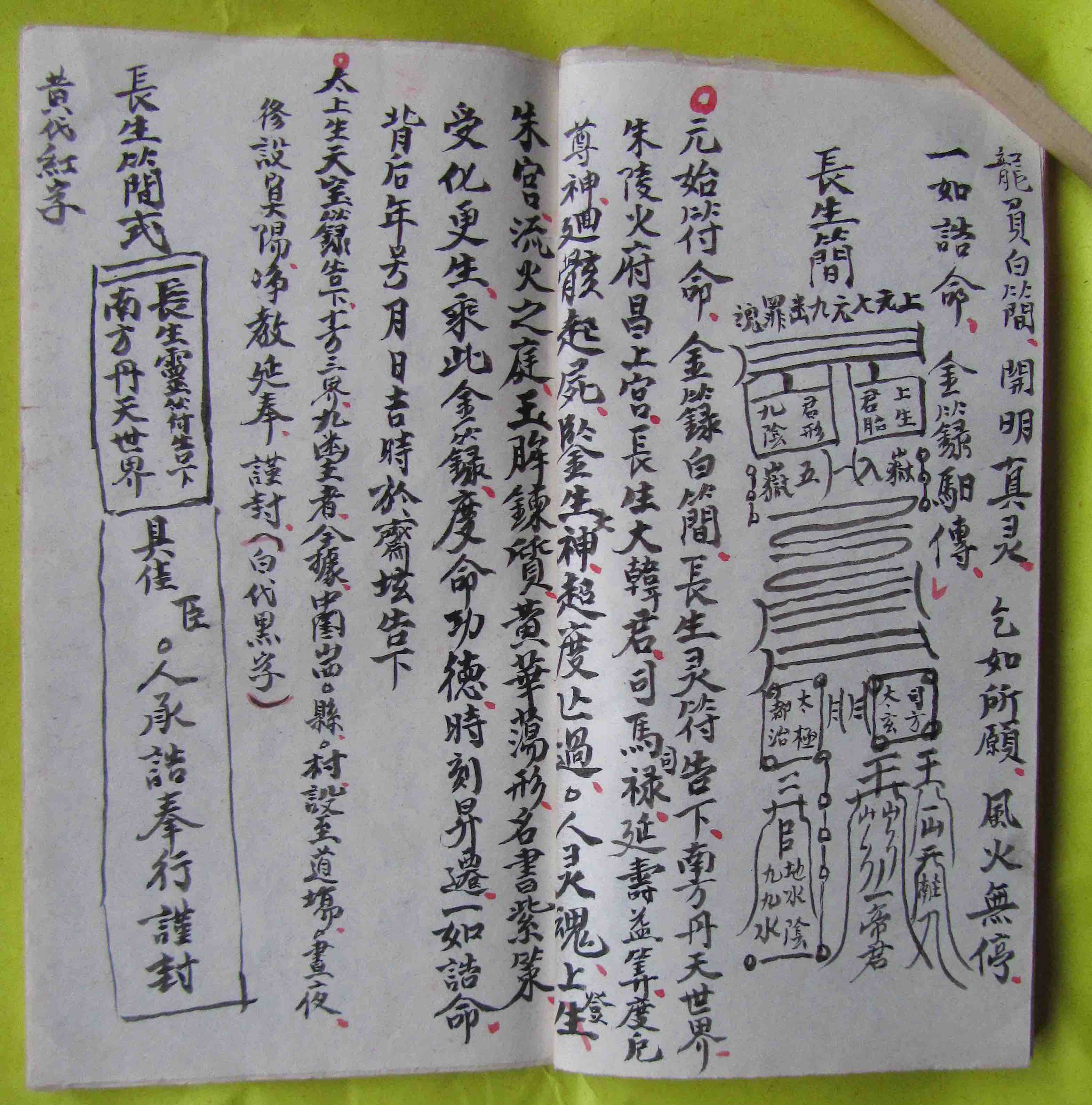

Back in north Shanxi, in

Back in north Shanxi, in