As weird holidays go, this is pretty weird…

To supplement my various articles on particular themes (a ghost village, a funeral, the murals of Artisan the Sixth, Elder Hu, In search of temples, and so on), this diary records the more domestic side of my recent trip chez Li Manshan—like my notes on our French tour last May, the kind of thing one hardly finds in inscrutable accounts of hallowed Daoist ritual.

As I land in Beijing, pausing only to catch up with my wonderful hosts Matt and Dom and to buy a SIM card, I take the midnight train to Yanggao—smashing my personal best time for Fastest Ever Escape From Beijing. You may like to begin by reading my updated description of my first couple of days there.

Catching up

Despite improved transport and smartphones, progress seems superficial. This is still another world from the skyscrapers and Party congresses touted by the international media. Like anywhere else in the world, indeed. And it’s hard to see evidence of greater repression—people are well used to it.

Li Manshan’s home village of Upper Liangyuan still has some over six hundred dwellers, which counts as a lot round here; but it seems forlorn, stagnant. It’s ever clearer that the rural population is “left behind”—elderly people sitting outside awaiting their turn. Litter remains an intractable problem, blighting what might almost be an idyllic landscape.

Having been worked off his feet for many years, now that Li Manshan is in his 70s he’s giving way to Li Bin, who’s busier than ever. Li Bin has three funerals to do today, one a solo attendance at the grave (“smashing the bowl”, “without scriptures”) for a Catholic family, who still need the procedures for the date and siting of the burial. On the 17th (or rather the 2nd, chu’er—I soon get used to the lunar calendar) he has to smash two more bowls.

So now Li Manshan only works nearby—decorating coffins, doing grave-sitings and visits to determine the date for burials, as well as the occasional funeral. Soon after I arrive he zooms off on his motor-bike to Yangguantun to decorate a coffin. I’m happy to try and sleep off my journey from London.

Visitors are always announced by a barking dog, like a doorbell. The Lis have a new doggie, rarely off its tether by its kennel in the courtyard. It’s frozen. When I tell Li Manshan’s wife (busy making funerary headgear) about our poncey UK winter gilets for dogs, she shrugs, “He’s fine, he’s got fur ain’t ‘e?!”

Li Manshan’s (only) disciple Wang Ding returns from a funeral to unload the decorations for the soul hall, now improved and more convenient. Renting out this equipment to funeral families is another source of income for Li Manshan. Giving Wang Ding a hand, I tell him I wrote a little post about him after our little French tour last year; he hasn’t got internet, so he will look at my blog at Golden Noble’s place. He can speak pretty good Yangpu, but even after all these years I find their dialect as tough as ever.

I hardly bother to wear my glasses any more—like clarinetist Jack Brymer, who when rehearsing a contemporary piece would wear his for the first five minutes, and then only keep them on if he thought it was worth it…

The domestic routine

Li Manshan’s first tasks on rising are to fold the bedding, take out the chamber pot, fetch kindling for the kitchen stove and our little stove in the west room, and boil water. He does his bit with the housework: sweeping, mopping, stoking the stove, preparing water—though he leaves most of the cooking to his wife. The little coal stove is cute and effective, but mafan. At last I learn that the central foyer is called tangdi 堂地. Both living rooms are equipped with a low wooden table, actually rather handsome but covered in plastic, to place on the kang, used for meals and writing. Plastic rules OK—and a jolly good thing too.

Our diet consists mainly of baozi dumplings, [1] noodles, crêpes, mushrooms, eggs, bits of meat, meatballs, doufu, cabbage, nuts. Sometimes our meals evoke the classic film Yellow Earth—indelible image of the fieldworker overwhelmed by the sheer enormity of poverty and traditional culture. But we giggle a lot too.

Again Li Manshan stresses how much he prefers country life. I soon get used again to its basic routines, not least visits to the latrine in the southwest corner of the courtyard—taking paper (The Thoughts of Uncle Xi would be useful, but it’s not to hand/arse), and a torch if dark, to balance on a ledge; adjusting trousers, squatting (not getting any easier)…

Amazingly, for my visit in autumn 2013 Li Manshan modified his old latrine, building a little roofed pier (so to speak) over a floor on pillars projecting from the spacious pit. Like the world, it was built in seven days. After designing it on paper, he borrowed 230 bricks, as well as stone slabs, tiles, and so on, from neighbours; then he got down and dirty over a week at the height of summer. I felt embarrassed, but he pointed out that it would be good for them too.

We refer to it as The London Embassy (Lundun dashiguan, pronounced like “Taking turns to squat in the big shithouse”). The great Beijing cultural pundit Tian Qing even bestowed his illustrious calligraphy on Li Manshan, albeit in the more polite version.

So (thanks to me) the latrine is pretty comfortable, but it makes a suitable image to imagine the poverty of the olden days (including the Maoist era—a sobering contrast with the bright propaganda posters of the time): the old and infirm trudging to an open pit in the snow, with no paper, no sanitary products, no torches in the dark.

I’m so pampered, compared to Li Manshan’s lifetime “enduring suffering” (shouku 受苦). From my book (pp.132–3):

Shoulders unable to carry, hands unable to grasp, soft and sensitive skin…

Coming across this phrase in 2013 as I made inept attempts to help Li Manshan with the autumn harvest, I thought it might have been coined to parody my efforts. Rather, it’s a standard expression used to describe the travails of urban “educated youth” in performing physical labour after being sent down from the cities to the countryside in the Cultural Revolution to “learn from the peasants”. The experience was a rude shock for such groups all over China; brought up in relatively comfortable urban schools to believe in the benefits of socialism, and often protected from understanding the tribulations of their own parents, they were now confronted not just by the harshness of physical labour, but by medieval poverty.

Li Manshan is thrilled with my little gift of a set of UK coins, working out which is which. He proudly offers me a black banana, white and tasty on the inside, but decides to eat it himself; we have a giggle over glossy modernized bananas (cf. “banana republic, but minus the bananas”). His wife passes the time by playing “matching pairs”, a kind of dominoes. A female friend of hers drops by for a chat. They’re all very humorous, beneath a somewhat dour exterior. Li Manshan and his wife seem like counsellors.

In reply to villagers’ curious enquiries about how many kids I have, Li Manshan is now in the habit of replying wu, which they hear as “five” 五 but in his creative head means “none” 无. This surprisingly shuts them up—I worry about having to embroider stories about their careers, my numerous grandkids, and so on, but no. Anyway, Li Manshan would be up for this. He observes that since my surname is Zhong 钟 (Clock), my son might be named Biao 表 (watch).

We share a nice supper of noodles, and more dumplings. The CCTV evening news is on as wallpaper [Breaking news! CCP holds meeting! Xi Jinping still in power! Old gits in suits dead bored!]. It’s ignored until the weather forecast comes on, but Li Manshan loves the nature programmes.

“Wotcha doing when you get back to Beijing?”, he goes.

“I’m going to be giving lectures (jiangke)…”

His local dialect, or his lively mind, instantly converts this to jieka “stammering”:

“Old Jonesy, you don’t have to go back to Beijing to stammer—you can just keep on stammering away here!”

I manage both.

Writing

Though Li Manshan is doing fewer funerals these days, he has always got ritual paperwork to do—whether it’s writing talismans, shaping paper for funerary artefacts, or writing mottos for the soul hall (our film, from 10.41; Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.194–200).

He’s bought big reams of thick paper from Yangyuan county. He recalls that when Li Qing recopied the ritual manuals in the early 1980s, mazhi hemp paper was available from the Supply and Marketing Co-op.

One day our siesta is disturbed by a group coming to ask Li Manshan to “determine the date”. After seeing them off he spends the rest of the afternoon writing several dozen sets of four-character funerary diaolian mottos for the soul hall (my film, from 10.43)—enough for a couple of months. Again he recalls how Li Qing used to write them in the scripture hall for each particular funeral. I devise a new game: arranging the squares in a different order to make a popular phrase or saying. For starters, how about 東方妙,西方福 (“oriental mysticism is all very well, but things are kinda cushy over here”).

A trip into town

One morning we call up the wonderful Li Jin to arrange a nice quiet lunch in town, just the three of us. Li Manshan’s wife chooses a posh shirt and jacket for him.

In 1953, when he was 8 sui, Li Manshan walked into town with his auntie to see the big xiangong parade there. Now we walk up to the main road to catch the No.2 bus into town; it arrives soon, a mere 3 kuai each, taking under half an hour—fun, and good to be independent. I go to have my head shaved at my favourite barbershop, and we meet up with Li Jin at Li Bin’s funeral shop. But then Li Manshan’s (much) younger brother Third Tiger shows up too, and he drives us in his posh car to a posh restaurant (attached to a posh hotel) up a little hutong, with no sign (which is always a good, um, sign)—we’re the only customers. But then entrepreneur Ye Lin (another old mate, formerly head of the Bureau of Culture) arrives too, and Li Bin; so altogether it’s less of a quiet meal than I hoped.

Third Tiger has brought a case of Chilean 2011 Cabernet Sauvignon from Central Valley, a gift from a friend. We polish it off, though later the ganbei toasting seems a bit unsuitable…

Third Tiger had been looking forward to early retirement from his important state job—even claiming in my film (from 55.23) that he’d like to get back to Daoist ritual—but it won’t be happening any time soon. He’s done well as a Party cadre, his only flaw being that he can’t really hold his drink—this should surely be the first question on the application form:

How much baijiu liquor can you knock back before you fall over?

Inevitably Third Tiger foots the bill. I remind my companions of the donkey joke—I’m inadvertently “cadging a free meal wherever I go” again…

After lunch, Li Bin takes us on a fruitless visit to the Cultural Preservation Bureau to learn that the compilation of Yanggao temple steles is still not published. Then we drop in on a shop up the road to sort out a standoff between my camera and my Mac; the guy is even more pissed than me, but does a fine job. We exchange cigarettes, and he refuses any money.

Li Bin is happy to take us home to Upper Liangyuan, and on the way we drop in on the grandson of the great Li Peisen at his funeral shop, to see if he can show us the three manuals not in Li Qing’s collection, which I didn’t copy. He and his wife seem affable, but he can’t find them. It’s hard to know if he’s being cagey: he does show Li Manshan Li Peisen’s thick Yuqie yankou volume, so maybe he really can’t find the others. I ask him, without much hope, to call Li Bin if he does find them. Li Manshan cares more about this than I do.

I’ve also been wondering if the related Wang lineage in Baideng has any ritual manuals we haven’t seen, but when Li Manshan calls up Wang Fei there, he says they have no more than him.

More Heritage flapdoodle

Next to the main sign above his funerary shop, Li Bin has optimistically put up a new sign: “Hengshan Daoist Music, Training Base”.

This pie-in-the-sky still has precisely no takers, but Li Bin remains involved in a mysterious project with the county Bureau of Culture. We all laugh at the emptiness of the title—but it acts like a protective talisman, a kind of insurance policy.

Pacing the Void: Old Lord Li gets online

Like me, Li Manshan got his first smartphone after returning from France last year. He can read WeChat messages, but hasn’t cared to try and get online—yet. I think he can do it. Actually, WeChat doesn’t seem such a big deal here—sure, the younger people are on it, but the main way of communicating is just phoning. So there.

Getting online with my Mac thanks to the wifi of Li Manshan’s cool shepherd neighbour, I show him the charming TV version of The Dream of the Red Chamber with child actors. He loved reading the novel in the 1980s.

I give him a guided tour of my blog, starting with the posts I wrote about our French tour last year (e.g. here), my tribute to his carpentry skills, and the trio on Women of Yanggao (starting here). We look further at the ritual paintings in Li Peisen’s collection, which leads us to seek murals by Artisan the Sixth.

Then I introduce him to my other world, telling him about Yuan Quanyou, Hildi, and the 80th-birthday party for the great Stephan Feuchtwang where Rowan and I played Bach on erhu and sanxian—after listening to the recording there (now also sounding a bit crap), I try to attone by playing him Sun Huang’s astounding Saint-Saens (or Sage Mulberry, as he’s known in China), but he’s underwhelmed—the conservatoire erhu is of even less relevance to him than to me. And he’s none too clear about the qin zither, despite painting it regularly on coffins (my film, from 18.30).

Li Manshan decorates a coffin, 2013. Top: qin zither.

I tell him again about the adorable crazy Natasha, showing him my tribute to her—it was he who helped me regain the will to live after her death in 2013.

Over the next few days Old Lord Li becomes ever more scholarly, devouring the new book on the modern history of the county (only up to 1949, alas!), the gazetteer, and all the online stuff I show him. (You may note that he has reverted to his old hat—was the baseball cap he wore in France a haute-couture choice to impress the laowai?!)

He gets into Ming reign-periods online. I show him the Baidu article on the 1449 Tumu incident (very near Yanggao), making the link with the disgraced palace eunuch Wang Zhen and the Zhihua temple. As he gets hooked on some pre-Tang story in the county gazetteer, I turn the tables on him, commenting “I dunno about that, I wasn’t even born then!”

As he gets used to scrolling on my Mac keypad, I show him the blurb for the Chinese introduction to the already-voluminous Daojiao yishi congshu series, which he reads carefully. When I show him Hannibal Taubes’ amazing site, he thinks that Yanggao temple murals are not so well preserved as those of Yuxian—but I suspect it could also be that Hannibal is really on the case.

I tell Li Manshan of the useful saying “When the rites are lost, seek throughout the countryside”, which is always a succinct way of explaining what we’re doing traipsing around poor villages.

On my blog he’s interested to pore over ritual manuals from other areas. I find an online text for the pseudo-Sanskrit mantra Pu’an zhou, which they never sang, only played on shengguan. When we listen to my recording of Ma yulang with the Gaoluo ritual association (playlist # 10, with commentary here), he’s shocked at how crap they are! I explain that they’re an amateur group, not like our occupational Daoists working together daily. But he’s curious to learn if the melody is similar to their version, a question I haven’t yet addressed.

We discuss the Kangxi yun section in the hymn volume that Li Qing recopied in 1980—I’ve often wondered what it’s doing there, as part of a series of shuowen solo recitations formerly used for the shanggong Presenting Offerings ritual segment. It was actually written not by the Kangxi emperor but by his father Shunzhi. The version copied by Li Qing is a variant.

As we read up further, we now speculate that since Kangxi saw the poem on a visit to Wutaishan, and as Buddhist ritual manuals do contain poems, it could have got into one such manual there; spreading further north, it might thence have got into Daoist manuals too—which, after all, contain plenty of Buddhist elements (my book, e.g. p.226).

As we read up further, we now speculate that since Kangxi saw the poem on a visit to Wutaishan, and as Buddhist ritual manuals do contain poems, it could have got into one such manual there; spreading further north, it might thence have got into Daoist manuals too—which, after all, contain plenty of Buddhist elements (my book, e.g. p.226).

I wonder if the title Kangxi yun is distinctive to the Li family. If Li Fu copied it from the manuals of his master in Jinjiazhuang, it wouldn’t have been at all old when it was copied by the Zhang family Daoists there. More work for a historian there… Li Manshan buries himself in the Baidu articles on Shunzhi’s mother and Nurhaci.

He knows nothing of Trump, Syria, or the Ukraine famine. While envying him his blissful ignorance, I embark on a political education session; he reads avidly when I show him the relevant Baidu articles. The article on the Ukraine famine looks rather good—though one can hardly expect Baidu to compare it to the Chinese famine following the Great Leap Backward.

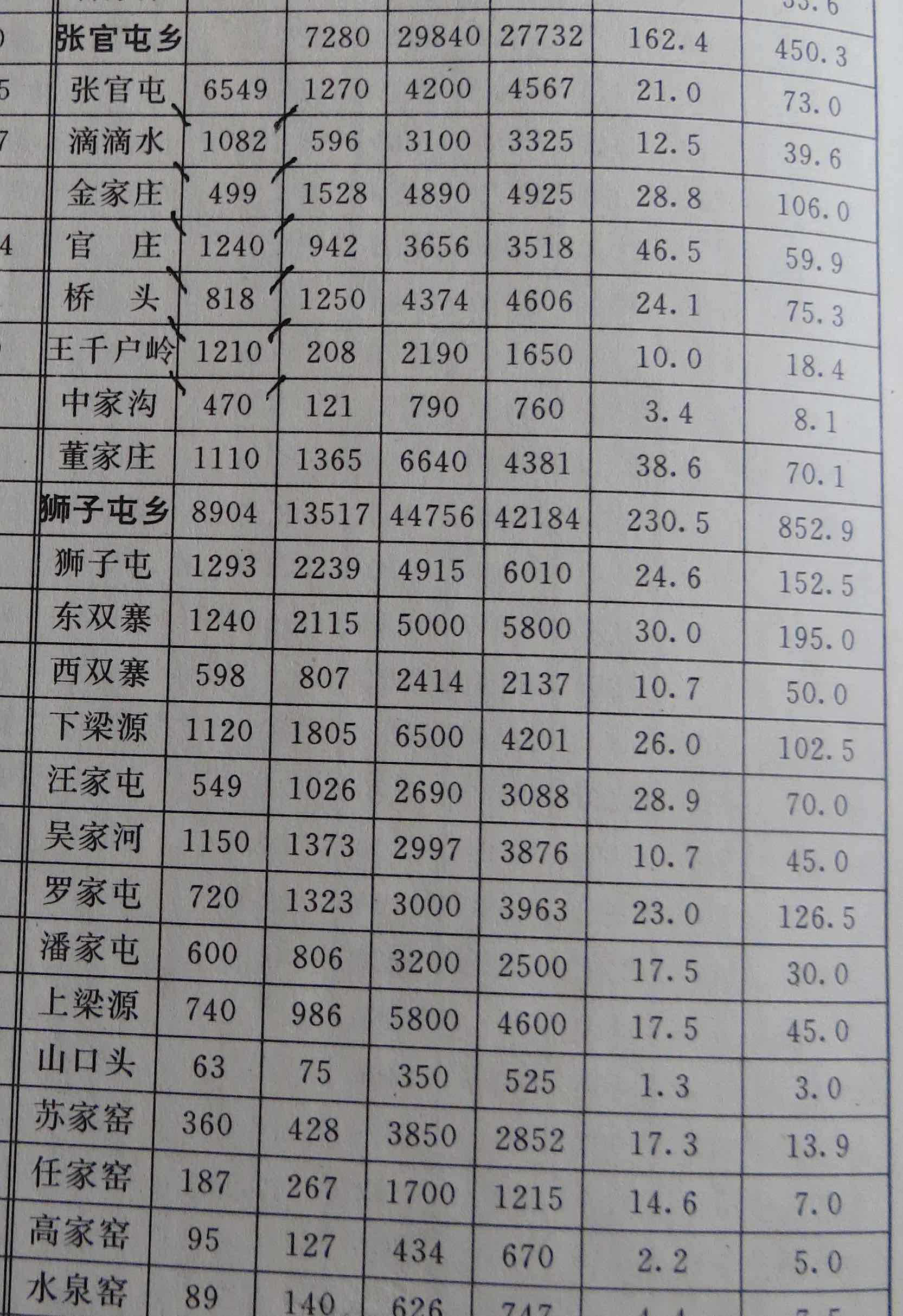

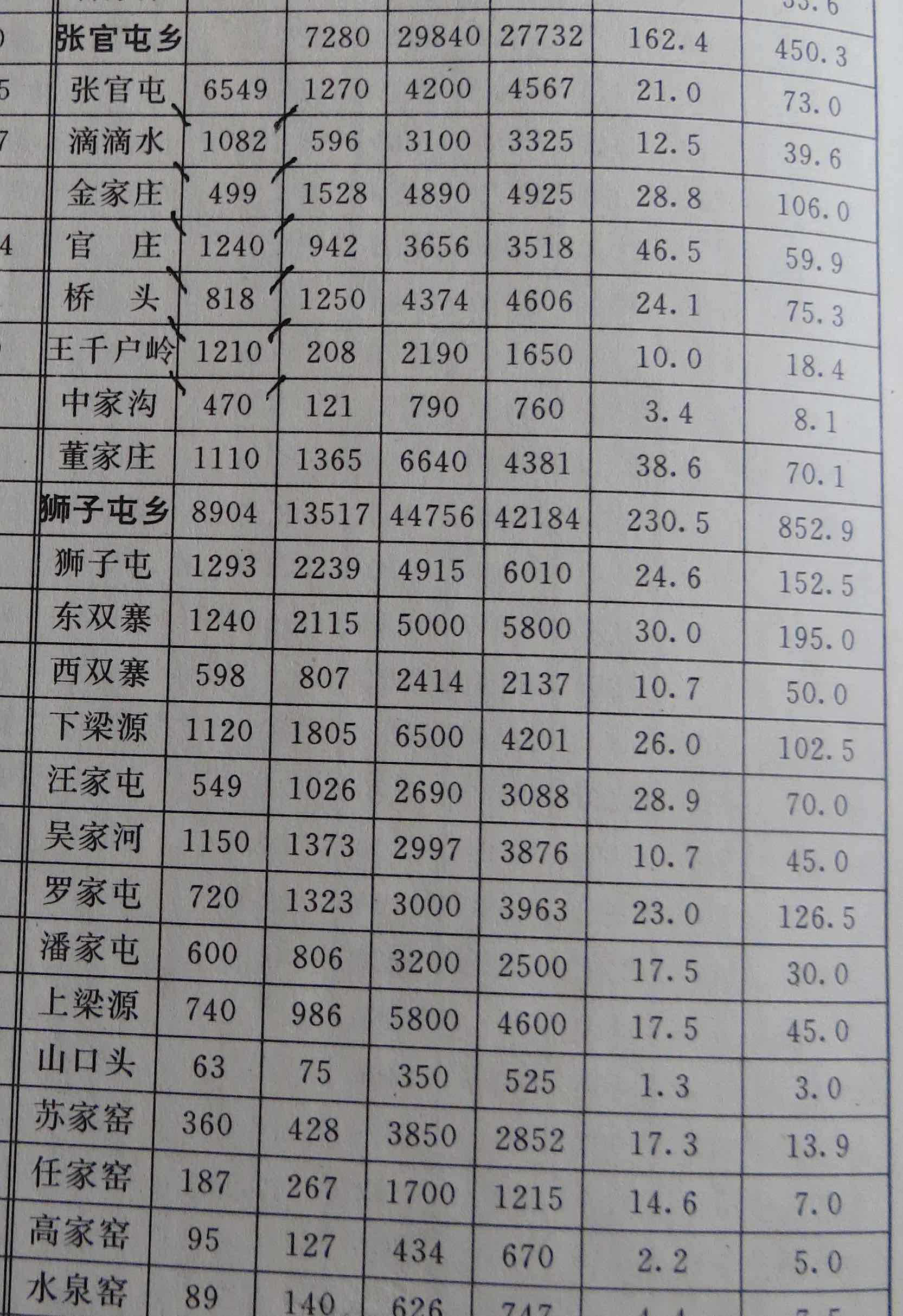

After returning from a brief trip to Waterdrop 滴滴水 village with Li Bin, I check the 1948 and 1990 population statistics (first two columns below) in the county gazetteer, but they seem incongruous. Old Lord Li inspects the table for the whole of Zhangguantun district and deftly corrects them. Clever guy!

Born at a different time in another place, Li Manshan might have become a university professor.

2nd moon 28th

As yet another idée fixe in Airplane goes, “Looks like I picked the wrong day to” get my head shaved—it’s really rather cold. Li Manshan kept reading till late last night. We stay home for a study day. He fields another “determining the date” request by phone.

Before midday a couple comes for a prescription about her illness. They’ve come all the way from Datong county, learning of his reputation on the grapevine. Sure, people may also consult mediums, and of course hospitals—the latter terribly expensive, but as Li Manshan observes, their best bet.

The mood is serious as ever when the wife throws the coins and Li Manshan writes down the results. They watch him work it all out, in silence; then she asks questions, the conversation deepening. Li Manshan feels his role (often) is to console them, to lend moral support. As he later tells me, in fact the prescription looks ominous, and mostly he trusts the coins, but he can’t tell them “You’ve had it”, can he? They persuade the couple to stay for lunch (baozi dumplings, cabbage and doufu, onions), washed down at the end with water from the pot. It’s a friendly and sincere scene. They only paid him with five cigarettes, and Li Manshan was fine with that.

Li Manshan’s siesta is devoted to further reading, and he’s only just nodded off when another guy comes for a prescription.

Another great supper: thick-sliced noodles with eggs, dunking meatballs in the broth. Li Manshan glances over at the news, nudging me—some Party bigwig is being interviewed, the caption reading:

中国人大代表 Zhongguo Renda daibiao

Representative of the Chinese People’s Congress,

which he brilliantly converts from three binomes into

中国人,大代表 Zhongguoren dadabiao

Chinese bloke, big cheese.

We fall about laughing. I just love the way this man’s mind works! The following week I’m showing my film at People’s University in Beijing, which is also abbreviated as Renda—so I manage to press the expression into service there.

I clean my teeth in the courtyard, enjoying using my fancy electric Rabbits Don’t Shit, sorry I mean toothbrush (its first outing in China). Since Li Manshan always shoves a fag in my gob as soon as I get back anyway, I beat him to the draw. Whenever I spot an unfamiliar brand, I ask him, “Landlord? Poor peasant?”

3rd moon 1st (chuyi)—which, I note guiltily, is Saturday.

Right: sunflower stalks stored for use in making funerary treasuries.

OOH it’s snowing! I’ve been hoping to go in search of more Daoists to Yingxian county with Li Bin and bright young Taiyuan ethnographer Liu Yan, but my carefully laid plans come to nought; the motorways are closed. Li Manshan sweeps the pathway to the latrine, then zooms off back to Yangguantun to smash the bowl in a simple burial for the poor family there. When he decorated the coffin on 2nd moon 25th it was the fourth (not third) day after the death. He explains that there’s no difference between rich and poor in determining the date: it may turn out that poor families also have to store the coffin for over twenty days.

I discreetly perform much-needed ablutions. Li Manshan comes home frozen, unable to see through the snowstorm on his motor-bike. Gradually it eases up.

I show him my photos of the funeral I attended yesterday. He’s always been a laissez-faire leader, but even he draws the line at Wu Mei playing drum while on his mobile. We get a riff going:

“Maybe he was following the drum patterns online?!” he jokes.

“Oh yeah, right—I always felt sorry the so-called Hengshan Daoist Music Ensemble because they were too poor to afford music stands, but now they can read from their mobiles! You’re dead keen on ‘development’, aren’t you?!”—referencing the rose-tinted cliché common in online articles about him.

“Naughty disciple!”

“Naughty master! 青出于蓝。。。”

Wang Ding turns up on his dinky sanlun truck and we help him unload more altar decorations into the south room of the courtyard, redecorated as the village Training Base of the so-called Hengshan Daoist Music Ensemble—and thus, like its town counterpart, entirely unused.

3rd moon 2nd (Sunday, known as libai ba, eighth day of the week, as on their electronic wall-clock)

Foggy at first, gradually the sun comes out. For the first time Li Manshan worries about his cough, and resolves to quit smoking—which, impressively, he manages for nearly a whole hour. Actually he’s not smoking as much as in the old days when he was busy doing funerals with the band.

Having taken a siesta after our fascinating excursion to find murals by Artisan the Sixth, I go outside to clean my teeth, but yet again my oral hygiene is thwarted by the arrival of “Fag Devil” Li Sheng, who insistently shoves another fag in my gob. Typical…

I keep up with Tweety McTangerine’s latest lunacies by consulting the Guardian online. But I dissolve in fits of laughter at Stewart Lee’s latest offering there.

3rd moon 3rd

At 7am a guy comes to discuss some work. At 8.20 the formidable wife of an old friend of Li Qing’s comes to moan about her son’s marital problems. Li Manshan is courteous, but considers her “crazy”. I understand virtually nothing, but eventually she makes an effort with me as she pours out her grievances, slapping me regularly on the arm. Village poverty and problems seem intractable, despite advances and propaganda. The only solution touted is thorough urbanization, bringing its own worrying prospects.

Li Manshan isn’t feeling too well, but he takes a break from making paper artefacts to accompany me on a visit to the temple to Elder Hu in the Lower village.

3rd moon 4th

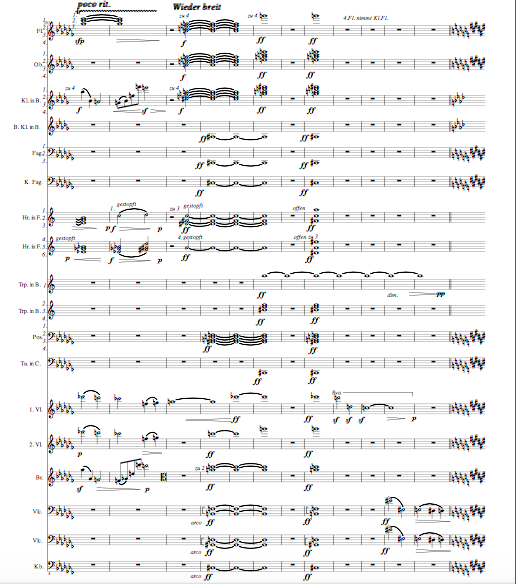

On our last day together, after returning from an intriguing trip to Jinjiazhuang, Old Lord Li suddenly thinks of the slow hymn Eternal Homage (Yong guiyi 永皈依), and we have a nice session on it. It’s one of his favourites, but they rarely use it, and now he can’t remember the opening. He can’t read cipher notation, only gongche solfeggio, so he gets me to sing it from Li Qing’s cipher-notation score. Their more recent green volume has gongche solfeggio underneath too, so he can just about follow it once I get him going.

So Li Manshan gets to record me singing a piece I barely know, but I never get to record him. Anyway he always sets off from a really low pitch, so the result tends to sound a bit like Tibetan chanting. When the band sings a cappella hymns for funerals, Golden Noble has a good ear for starting off on a pitch suitable for the range.

So Li Manshan gets to record me singing a piece I barely know, but I never get to record him. Anyway he always sets off from a really low pitch, so the result tends to sound a bit like Tibetan chanting. When the band sings a cappella hymns for funerals, Golden Noble has a good ear for starting off on a pitch suitable for the range.

In the version they learned, the first section ends after Fo you Niepan shi 佛有涅槃时. Li Qing’s cipher-notation score isn’t divided into sections, but their more recent green volume is. The latter uses the degree shang 上 as do—including the shengguan suites, which I find strange. Li Manshan is fine once he gets through the opening phrase.

We take a siesta before my journey back to Beijing, but soon wake up. Absurdly, he now asks me to transpose Li Qing’s cipher-notation score of the major shengguan melody Yaozhang into gongche solfeggio. Without thinking to consult the precious photos of Li Derong’s old score (which Li Manshan no longer has) I wrongly assume that it would use the early shengguan system with he 合 as do, but hey. After singing it for him as he records it on his phone, I explain to him that he’ll need earphones to play it back…

Li Bin has another busy day today, having to do two reburials as well as decorating a coffin, so I’ll take a cab to the station. This no longer feels so distant. Li Manshan insists on coming along to see me off, and we leave before 4, dropping his wife off at Baideng township for a hairdo. He refuses to let me pay for the cab. My total expenses for nine inspiring days in Yanggao came to 24 kuai—just over £2.

We take the ring road, passing loads of new high-rises, and bid each other a fond farewell. The station is virtually empty, and the train isn’t busy either.

Back in Beijing, I feel like a country bumpkin. Showing my film three times over the next week, I’m happy to make Li Manshan a big star there. After the last screening I call him up to report, and to wish him well before I go back to London.

[1] As in the poseur’s celebrated line (Fieldworkers’ joke manual No.37), useful when someone asks if you know any classical Chinese:

[smugly] “I studied the Four Classics and Five Scriptures—Confucius, Mencius, various dumpling shapes, I’ve studied them all!”

Wo xuedeshi sishu wujing—Kongzi Mengzi baozi jiaozi, dou xueguole!

我学的是四书五经。孔子孟子包子饺子,都学过了!

Oh well, it’s funny in Chinese—Trust Me I’m a Doctor (there goes another 200 kuai).

Similar story here!

As to Arsenal’s young star, I’m keen to get this headline in early:

As to Arsenal’s young star, I’m keen to get this headline in early:

“I am opposed to the death penalty,” he said without emotion, “except for my father.” […] “He was a criminal.”

“I am opposed to the death penalty,” he said without emotion, “except for my father.” […] “He was a criminal.”

As we read up further, we now speculate that since Kangxi saw the poem on a visit to Wutaishan, and as Buddhist ritual manuals do contain poems, it could have got into one such manual there; spreading further north, it might thence have got into Daoist manuals too—which, after all, contain plenty of Buddhist elements (my book, e.g. p.226).

As we read up further, we now speculate that since Kangxi saw the poem on a visit to Wutaishan, and as Buddhist ritual manuals do contain poems, it could have got into one such manual there; spreading further north, it might thence have got into Daoist manuals too—which, after all, contain plenty of Buddhist elements (my book, e.g. p.226).

So Li Manshan gets to record me singing a piece I barely know, but I never get to record him. Anyway he always sets off from a really low pitch, so the result tends to sound a bit like Tibetan chanting. When the band sings a cappella hymns for funerals,

So Li Manshan gets to record me singing a piece I barely know, but I never get to record him. Anyway he always sets off from a really low pitch, so the result tends to sound a bit like Tibetan chanting. When the band sings a cappella hymns for funerals,