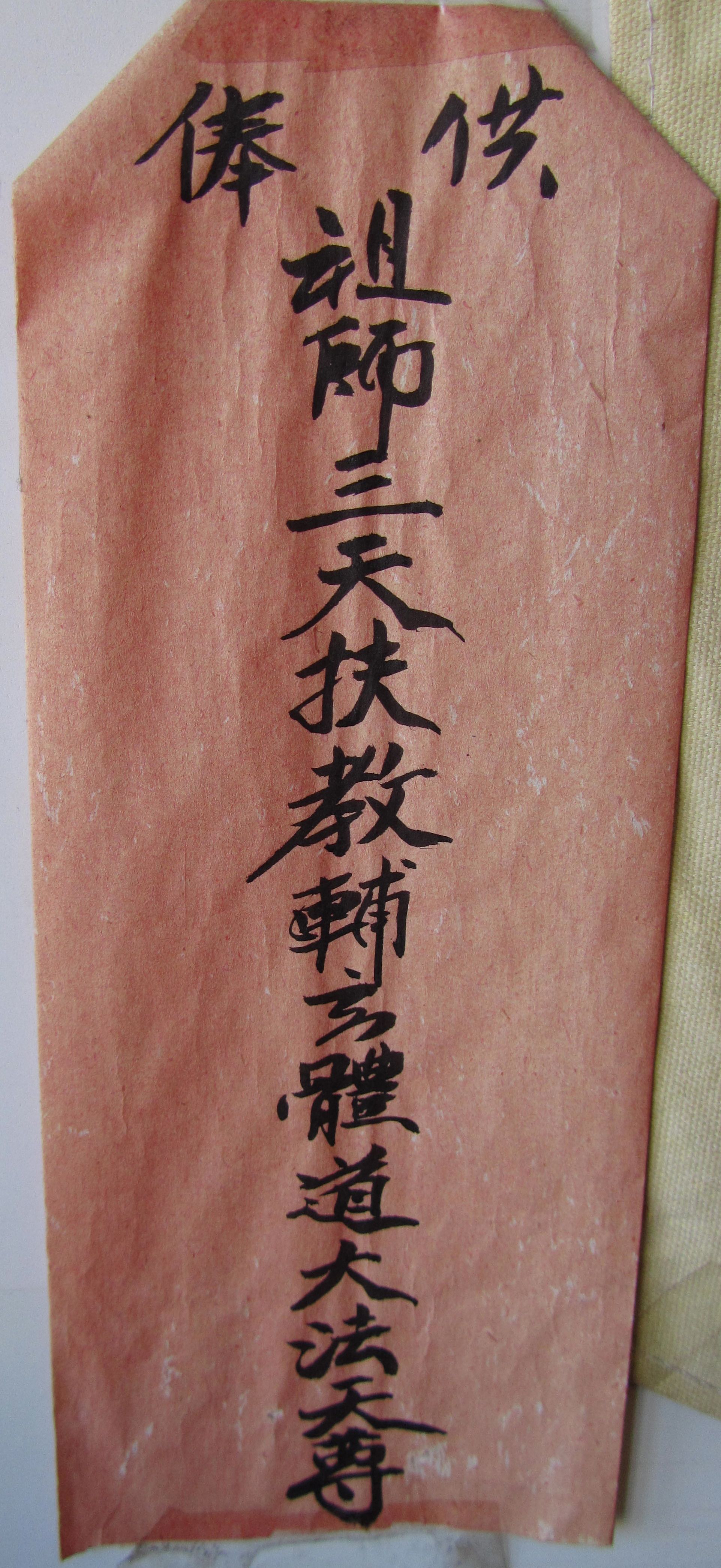

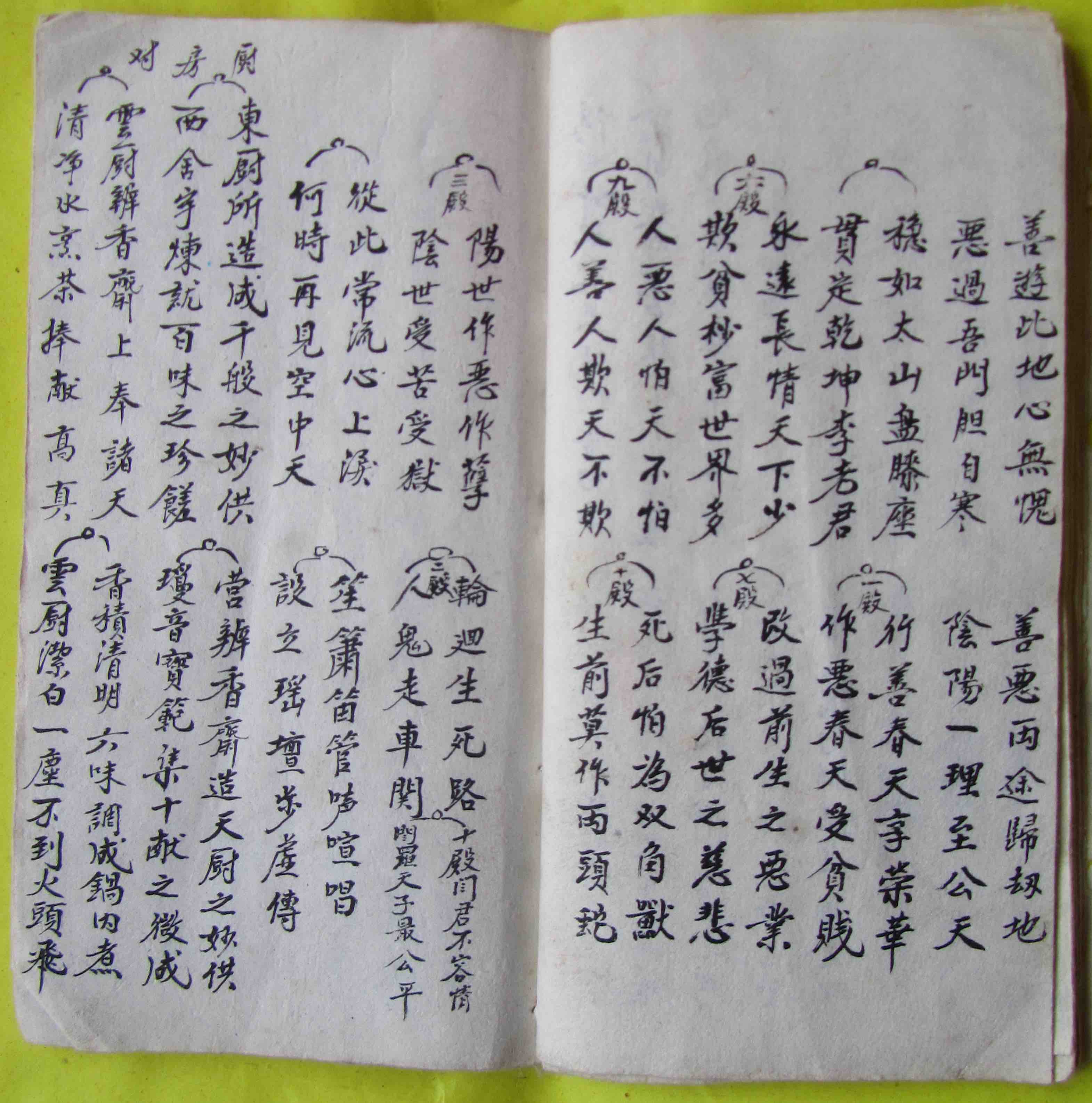

Ritual manuals of Li Manshan, handed down by Li Qing.

In 2013, as we survey a growing haul of over forty ritual manuals in Li Manshan’s collection, I exclaim: “Wow—I never realized you still had so many scriptures!” He chuckles whimsically: “Ha, neither did I!”

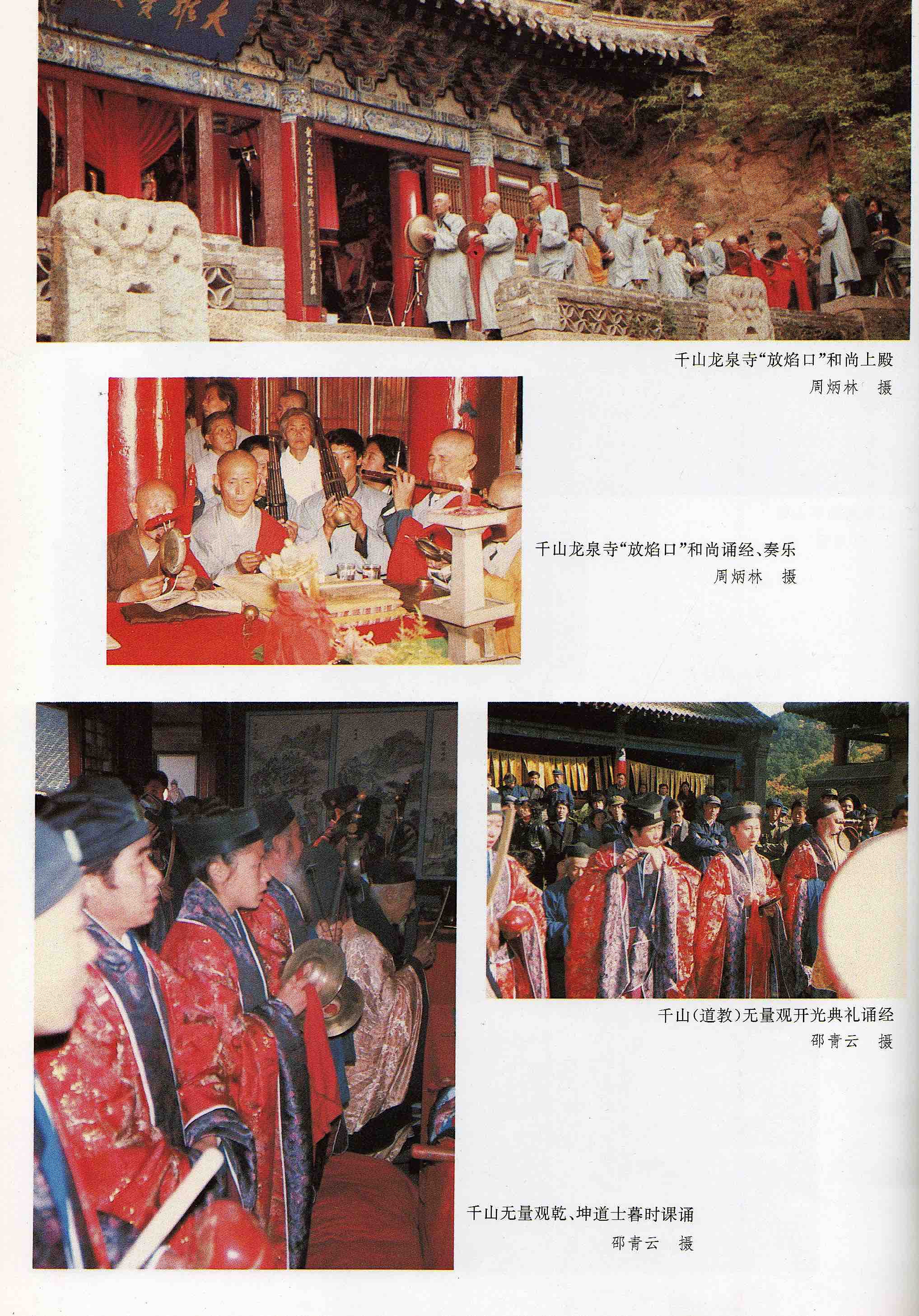

In the early 1980s, as the commune system crumbled, the religious revival of the 1980s began again to revolve around the performance of rituals for local communities keen to restore the “old rules”.

At the same time, scholars of Daoism tend to be more concerned with silent texts. But performance is primary—as I often remark on this blog, e.g. the Invitation and Presenting Offerings. As I observed here, giving primacy to ritual manuals is akin to having a fine kitchen and loads of glossy cookbooks, but drawing the line at handling food or cooking.

Further, ritual manuals were widely recopied, but we don’t always unpack the process, or the relation of the manuals to actual changing practice.

I described all this in detail in ch.8 and Part Four of my book Daoist priests of the Li family, which I summarize and adapt here (cf. my film, from 39.33).

From the late 1970s, as ritual was gradually coming back to life—families again able to observe funeral propriety, Daoists reuniting to recite their beloved scriptures—Li Peisen and his nephew Li Qing were also busy at home, painstakingly recopying the family’s old ritual manuals that had been lost or hidden away for fifteen years. This was part of a process then going on all over China, with Daoists piecing together as much as they could of local traditions that had long been under threat. [1]

You might suppose that for a group like the Li family, re-assembling a set of ritual manuals would be an essential condition for reviving their ritual practice in the 1980s. But it wasn’t. It was an important aspect of the personal striving of Li Peisen and Li Qing to reconfirm the tradition, but once they and their colleagues began doing funerals again, they had little need for manuals. Most of the texts they needed—for Delivering the Scriptures, Hoisting the Pennant, Transferring Offerings, and so on—were firmly engraved in their hearts after decades of practice, and there were no manuals for those rituals anyway. One might surmise that under ideal circumstances before the 1950s (itself a dubious concept) when the Daoists were performing ritual frequently without interruption, most of the manuals would be largely superfluous, as today.

As it happens, most of the manuals that Li Peisen and Li Qing copied (notably the fast chanted jing scriptures) were either for temple fairs, which were only to resume a few years later in a modest way, or for Thanking the Earth rituals, which hardly revived at all. So very few of these manuals were to be performed again. Can we even assume that they had once performed all the manuals that they now copied?

Li Manshan’s collection

Our discovery of the manuals has been a gradual process. [2] Over several centuries in medieval times, there were successive miraculous “revelations” of Daoist scriptures—from grottoes, or dictated by immortals. But our revelations of the Li family manuals were more prosaic. At the first funeral I attended in Yanggao back in 1991, I found Li Qing in the scripture hall consulting the old manual of funeral rituals copied by his uncle Li Peisen, and I photographed some pages—hastily and somewhat randomly. By the time of my visit in April 2011 I had still only seen two of Li Qing’s manuals. Over the course of successive stays with Li Manshan he rummaged around in cupboards and outhouses and discovered more and more volumes (for a complete list of titles in the collections of Li Manshan and Li Hua, see Daoist priests of the Li family, Appendix 2).

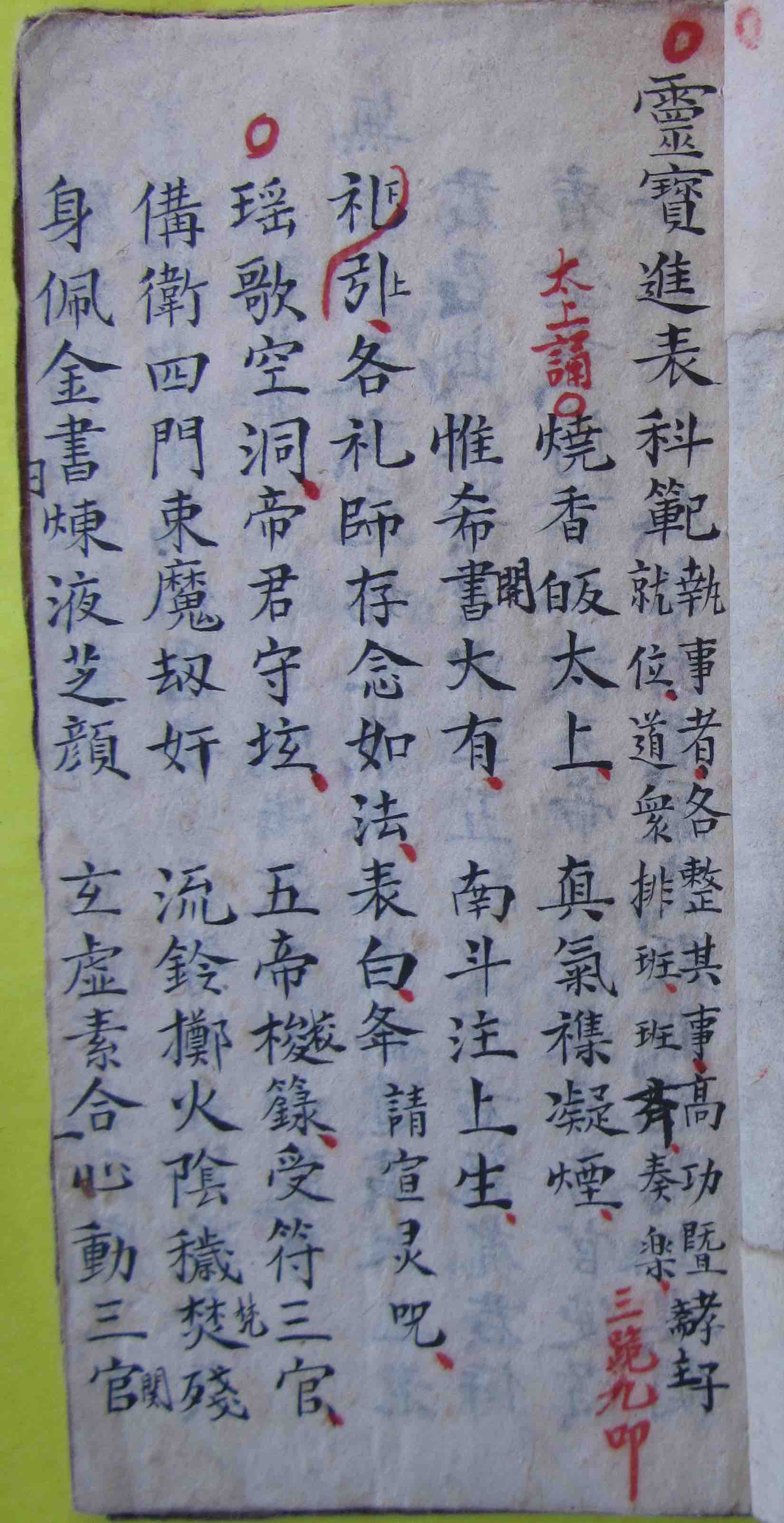

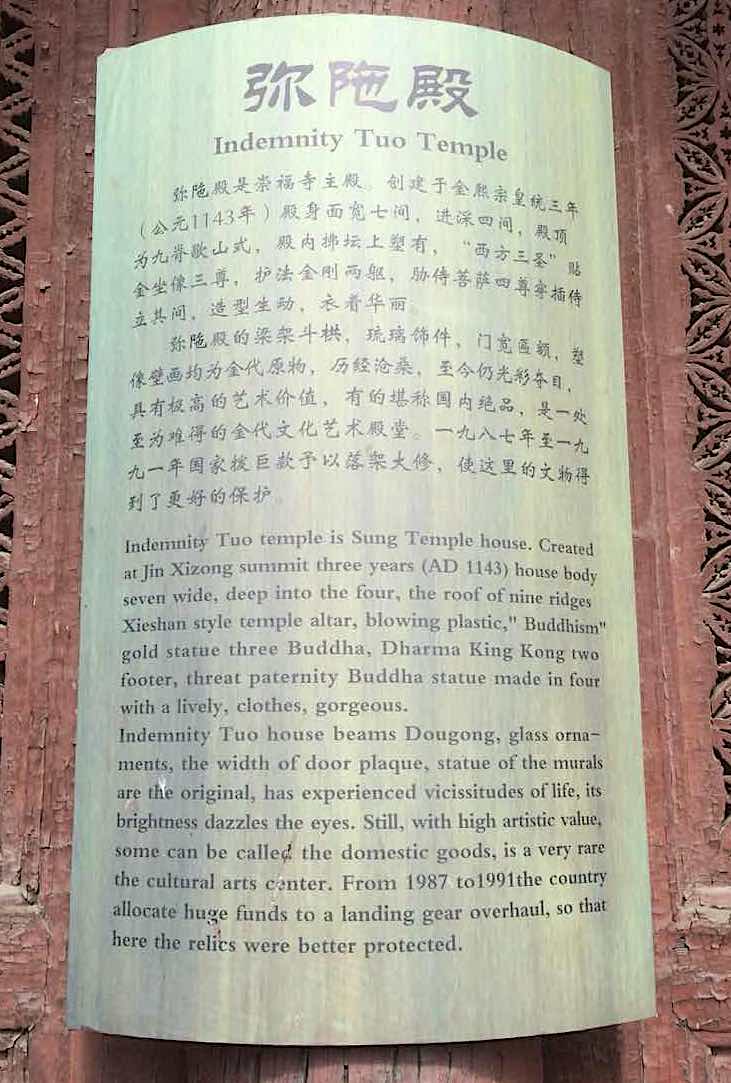

Pardon manual, Li Peisen, pre-Liberation. My photo, 1991.

The reason why so few manuals surfaced until I began enquiring in detail was not any conservatism on Li Manshan’s part. They are simply not used in current ritual practice, so he really never needed them, and they were just casually stashed away and forgotten. Now that I show interest, he too takes considerable pleasure in delving into them, but they are of no direct relevance to his current practice.

Each time that Li Manshan discovers more manuals, I busy myself taking complete photographs. This not only serves as valuable study material for me, but once we have copied them onto Li Bin’s computer it helps the family preserve them against any future mishaps.

Apart from their content and the historical significance of the undertaking, the manuals that Li Qing now copied move me because his personality leaps off the page in the assured elegance of his calligraphy. I have pored over hundreds of manuals copied by peasant ritual specialists since the 1980s, but few of them can compare to Li Qing’s hand. From the inscription that he wrote on the final page of the bulky Bestowing Food manual we can sense his pride and growing confidence:

Recorded by Li Qing, disciple resident in Upper Liangyuan village, the Complete Numinous Treasure Comprehensive Ritual for Bestowing Food manual in 69 pages, completed on the 3rd day of the 5th moon, 1982 CE.

Left: last page, shishi manual, 1982; right, Li Qing writing, 1991.

Li Hua’s Collection

In 2013 I learned that Li Hua has a collection of his father Li Peisen’s manuals, largely overlapping with that of Li Manshan.

Li Hua takes me and Li Bin to his son’s funeral shop, where they keep their scriptures and paintings. They bring them out and seem happy for me to take photos; but it’s getting late, so, reluctant to try their patience, I don’t ask to photo any complete manuals—most are identical to Li Qing’s copies anyway.

Ritual manuals of Li Hua, handed down by his father Li Peisen.

We go off together for lunch, all very friendly. I feel as if I am making a bridge between them; Li Bin agrees this has been a useful experience, and thanks me. But over the following days we visit Li Hua’s shop in vain; it has been locked ever since our first visit, and he isn’t answering his mobile. He seems to regret having shown us so much the first time. Later, after digesting my photos, we find there are at least four manuals in Li Hua’s collection that Li Manshan hasn’t yet found in his own.

Shelf-life of manuals

So the ritual manuals of the Li family Daoists that I have seen come from the collections of Li Peisen and Li Qing, handed down to Li Hua and Li Manshan respectively.

The earliest surviving manuals are by Li Peisen’s grandfather Li Xianrong (c1851–1920s) (left: his Presenting the Memorial manual). If manuals from the 19th century can survive all the destructions of the 20th century, then Li Xianrong and his colleagues in turn might have had a collection going back right to the lineage’s early acquisition of Daoist skills in the 18th century. And those manuals must in turn have been copied over successive generations of the lineage in Jinjiazhuang from whom Li Fu first learned. And so on.

Throughout the two centuries of the Li family tradition, ritual manuals had occasionally needed recopying. There are at least two reasons for copying a manual: when the old one becomes too decrepit, or if there are several Daoist sons. Daoists needed to recopy individual manuals occasionally as the older ones became dog-eared through use.

In south China scholars have found a few manuals from the 18th century, and even the Ming dynasty, but for the north even 19th-century ones are quite rare. Whether, or how long, Daoists kept the old manuals after copying them must have depended on their condition and on the taste of the custodian. Li Manshan observes that a Daoist may also copy manuals when he has more than one Daoist son. This seems simple, but presumably refers to a situation where the sons are likely to work separately—not necessarily long-term, but when there is simultaneous demand for more than one band.

So we can read the attempt by Li Peisen and Li Qing to recreate the complete textual repertoire in the early 1980s as a unique labour of love after an unprecedented threat of extinction, a reaffirmation of the family’s identity as Daoist masters. For over three decades during the Maoist era no-one had copied any manuals; “No-one was in the mood,” as Li Manshan reflected—another hint at the depression of the times. [3] As ritual practice slowly revived, Li Peisen and Li Qing now decided to do so because they realized the new freedoms brought hope. Their purpose was not to reflect current practice, which was still embryonic; thankfully, they sought to document as much of the heritage as they could, irrespective of which manuals had been used in their lifetimes or might now be needed.

So what was going through Li Qing’s mind as he put brush to paper? One surmises that for him, copying the manuals was partly a kind of atonement for having had to sacrifice so many old scriptures in 1966. But one also feels a great sense of optimism. The manuals he set about copying included many that even he had hardly performed. After all the false starts since 1949, was he so sanguine as to assume all these rituals would now become common again? Or was his instinct as archivist dominant?

Once again I kick myself to think that I could have gone through the manuals with Li Qing himself. When I met him in 1991 and 1992 I had no idea that he had copied so many—anyway I wasn’t yet expecting to study the family tradition in such detail. So now the main interest of going through the manuals with Li Manshan is to assess what has been lost. But that isn’t so simple either: it’s unclear how many of the manuals that Li Qing copied he himself could, or did, perform by the 1980s. I can’t even be sure he could perform all the texts in the lengthy hymn volume. When I casually comment to Li Manshan, “Shame you didn’t sit with Li Qing as he copied the manuals!” he replies, “I’m not a good son.” He is being neither ironic nor maudlin.

Of course, there may yet be some missing manuals that would further augment our picture of their former ritual repertoire. But impressively (given the usual stories of the decimation of ritual artifacts in the Cultural Revolution), Li Manshan now reckons that the surviving titles represent the bulk of those handed down in the family before 1966.

I can glean few clues about how this ritual corpus, and the texts within individual manuals, might have been modified over time. In the exceptional circumstances of the 1980s, Li Qing must have copied some manuals that he had never performed; and even for those rituals that he did perform, the version in the manual may differ substantially. Of course that was a special time, but a ritual manual from a given period doesn’t necessarily prove that the ritual was performed then, or in that form—not that the manuals actually tell us how to perform them anyway!

Moreover, early Daoists must have known a lot of texts from memory, as their descendants do today. Sure, they had a much larger ritual repertoire, and some lengthy texts required them to follow the manual. As it happens, the rituals that have fallen out of use are precisely those for which they needed to consult the manuals.

The process of copying

Li Qing may have inherited even more scriptures than Li Peisen, but he could retrieve only a few of them after the Cultural Revolution. With political conditions in Yang Pagoda more relaxed, Li Peisen had managed to hang on to his scriptures (and indeed his ritual paintings); so after he returned to Upper Liangyuan around 1977 it was these manuals that formed the basis for him and Li Qing to copy.

Li Peisen now lived not in his old home near Li Qing, but in another house just west of the site of the Palace of the Three Pure Ones. Li Peisen would copy a manual first, then lend it to Li Qing for him to copy too. Li Qing wrote alone, without help from anyone; no-one recalls them consulting.

On the covers, after his name Li Qing mostly used the word “recorded” (ji 記); only at the end of a couple of manuals did he write the word “copied” (chao 抄). The choice of term isn’t significant. The only manual in which Li Qing specifically wrote “copied from Li Peisen” is the Qian‘gao, dated the 21st of the 4th moon in 1982.

From collection of ritual documents, copied by Li Qing, early 1980s: template for funeral placard, including “China, Shanxi province, outside the walls of XX county,

X district, XX commune, at the land named XX village”.

When they began putting brush to paper, Li Peisen was 70 sui, Li Qing in his mid-50s. Having been taking part in rituals since the age of 6 or 7 sui, Li Qing would have been even more experienced had it not been for the interruptions since 1954; and by 1980 he had not performed rituals since 1964. Remember he had lost his father in 1947; since then he still had plenty of uncles and other senior Daoists to work with, but through the early years of Maoism he was beginning to rely more on his own knowledge.

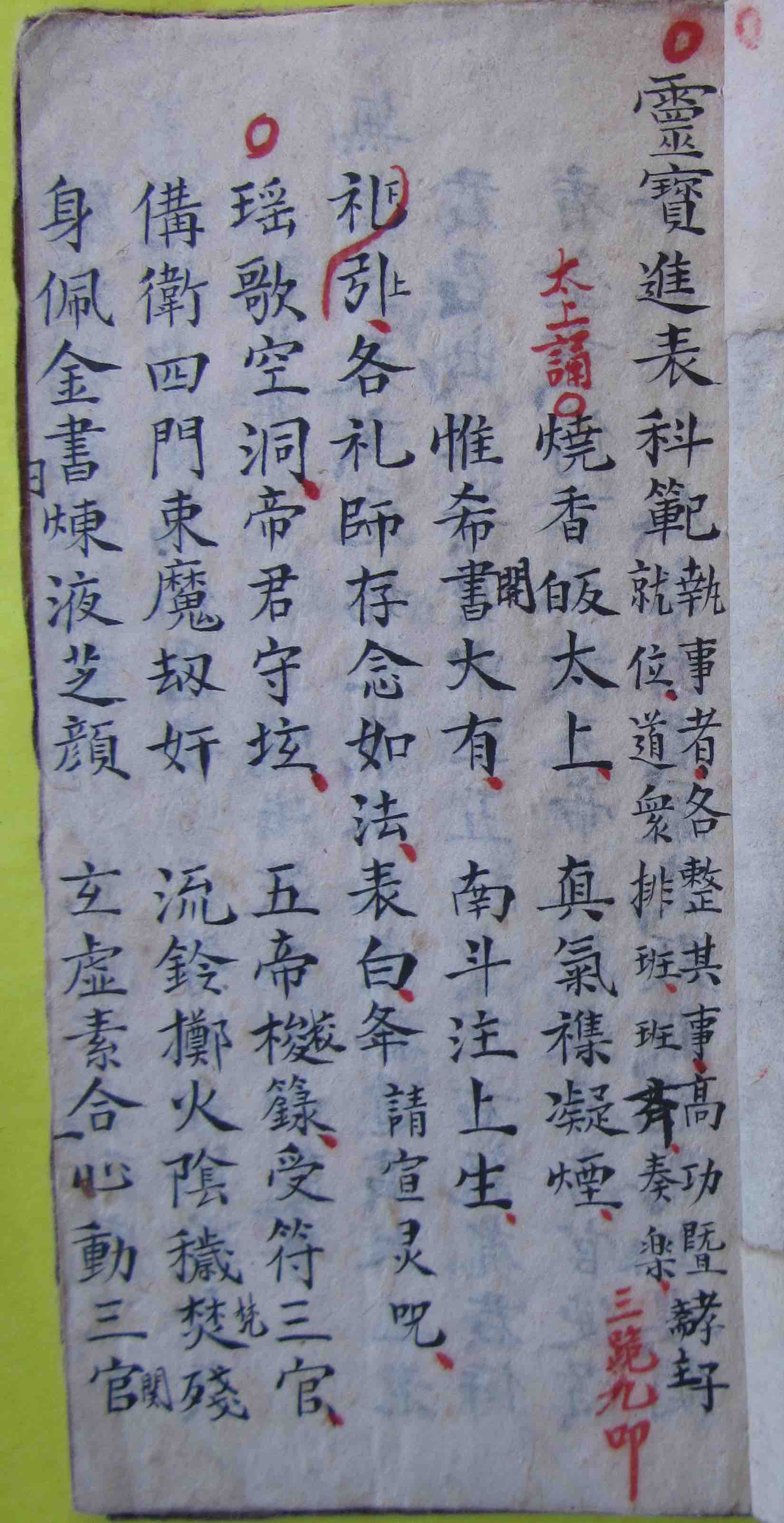

Writing was unknown to the great majority of the population, but despite ongoing material shortages there was no problem buying white “hemp paper” (mazhi). One summer day in 1980, with the sun pouring through the latticed windows of his main room, Li Qing took a low wooden table and placed it on the kang brick-bed. Removing his cloth shoes, he climbed onto the kang and sat cross-legged at the table. Putting on his thick black-rimmed glasses, he took out his brushes, inks, and inkstones, with the old manuals to hand, as well as a thermos of hot water. After folding some paper to make guidelines as he wrote the characters, he opened it out again; carefully dipping his brush in the ink he began to write, pausing as he went over the texts in his head, phrase by phrase. First he completed the whole text in black ink, laying each page on the kang to dry. Then, changing his brush and mixing some red ink in a separate receptacle, he drew circles showing the head of each new segment, and added punctuation.

Zouma score, written for me by Li Qing, 1992.

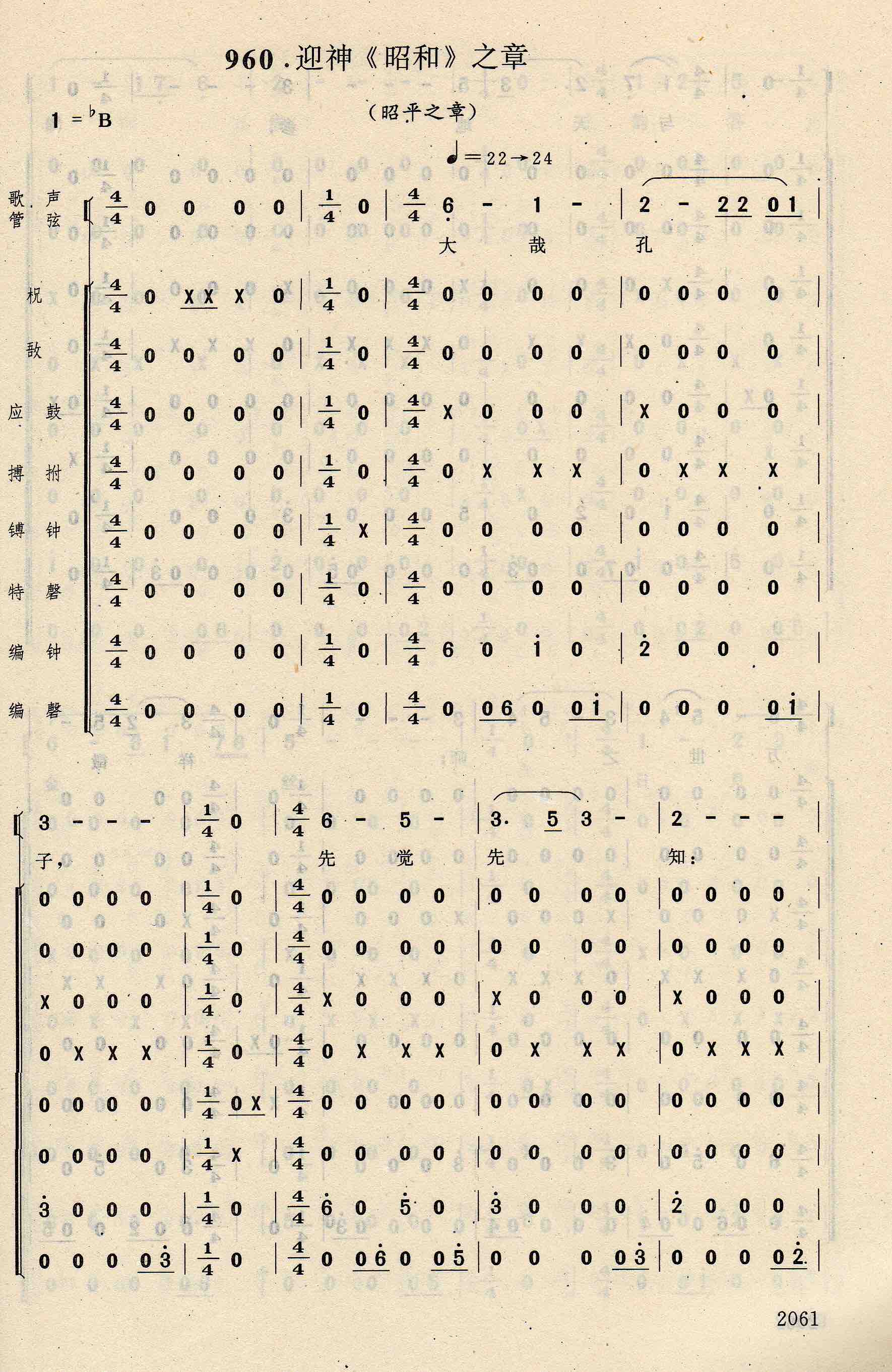

They do the same when writing a score of the gongche instrumental melodies—first writing the solfeggio notes in black, then later adding red dots that show the basic metrical pattern, rather like punctuating a text. I treasure a page of gongche notation of the exquisite shengguan melody Zouma (over opening titles of my film: playlist, #4, discussed here) that he wrote before my eyes in the summer of 1992, inscribing it for me at the end. When Li Qing finished writing a manual, he carefully folded each page in half, and then stitched them all together. Li Manshan tells me that it takes around three days to write a typical manual of around 15 to 20 double pages.

Incidentally, while the shengguan wind ensemble is a vital aspect of ritual performance, it was only later in the 1980s, after he had achieved the main task of salvaging the ritual texts, that Li Qing set to work recopying the gongche scores.

Formats

I don’t know if there was a standard size of paper in the late imperial period, or if folk copyists followed temple practice. The paper that Li Peisen and Li Qing used was mostly around 23 x 12 cm, but varied somewhat in both height and width. For the Communicating the Lanterns (guandeng) manual Li Qing used a larger format (29.5 x 14.5 cm), since this was one manual that they all consulted while reciting it together, so the larger characters would make it more convenient—and for the same reason, multiple copies were written. Other minor differences in size just depended on the availability of paper.

Since they were mostly copying existing old manuals, they followed the layout of text on the page of their models, beginning a new line for each couplet in regular verse and leaving spaces where suitable. Older manuals such as those of Li Xianrong are similar in size, with similar numbers of lines and characters. So old and new manuals alike have 6, 7, or 8 lines per (half) page, each full line allowing for 16 or 17 characters. [4]

They used the same paper for the cover pages, writing a title on the front cover, generally only an abbreviated one; the full title often appears within the volume, usually at the end. Some volumes contain several scriptures, and the title thus summarizes the contents, like Scriptures for Averting Calamity (Rangzai jing), which contains four scriptures. Li Qing didn’t write a title at all for what they call the hymn volume (zantan ben 讚嘆本)—Li Manshan only wrote the two characters zantan (“hymns of mourning”) on the cover when I wanted to take a photo of the manuals complete in 2011. We may never know its proper title.

The older manuals of Li Xianrong and Li Tang were in this same format, although in a few earlier volumes the title and the name of the copyist are written in two red strips pasted onto the cover page. One Thanking the Earth manual by Li Peisen from before Liberation has slips of red paper for the title and his name, followed by the characters yuxi 玉玺 “by jade seal,” suggesting some rather exalted ancestry.

But even these older manuals had no sturdier protection like wooden or cardboard covers. Nor do they use the concertina form that one sometimes finds on older scriptures elsewhere; this system is used not only in elite temples—I found it in use by amateur folk ritual associations in Hebei. The opening pages of such more elite early manuals also often show a series of drawings of gods. I found a substantial collection of such manuals—printed—in Shuozhou not far south, in the hands of Daoists whose forebears had spent time as temple priests. The concertina format is convenient to use if one is following the text while performing, turning the pages with a slip of bamboo between them. Another advantage of the format is that the pages don’t get so worn—the paper is so flimsy that with constant fingering it can soon get torn. But most of Li Qing’s manuals are in pristine condition, showing that they have hardly been used. Even Li Xianrong’s manuals, dating from around 1900, are remarkably well preserved.

Li Xianrong numbered the pages of his Presenting the Memorial manual, but the only time that Li Qing used pagination was for the melodic score in modern cipher notation that he wrote later. Li Qing wrote the date of completion at the end of a manual more often than Li Peisen. He usually wrote the CE (gongyuan) year, though sometimes he signed off with the two characters of the traditional sexagenary cycle; he always used the lunar calendar for the moon and day, as villagers still do today.

The manuals and ritual practice

The very first manual that Li Qing completed was apparently the hymn volume, whose date in the traditional calendar is equivalent to the 16th day of the 6th moon, 1980. Over the next few years he would sit down and copy a manual whenever he had a couple of free days at home.

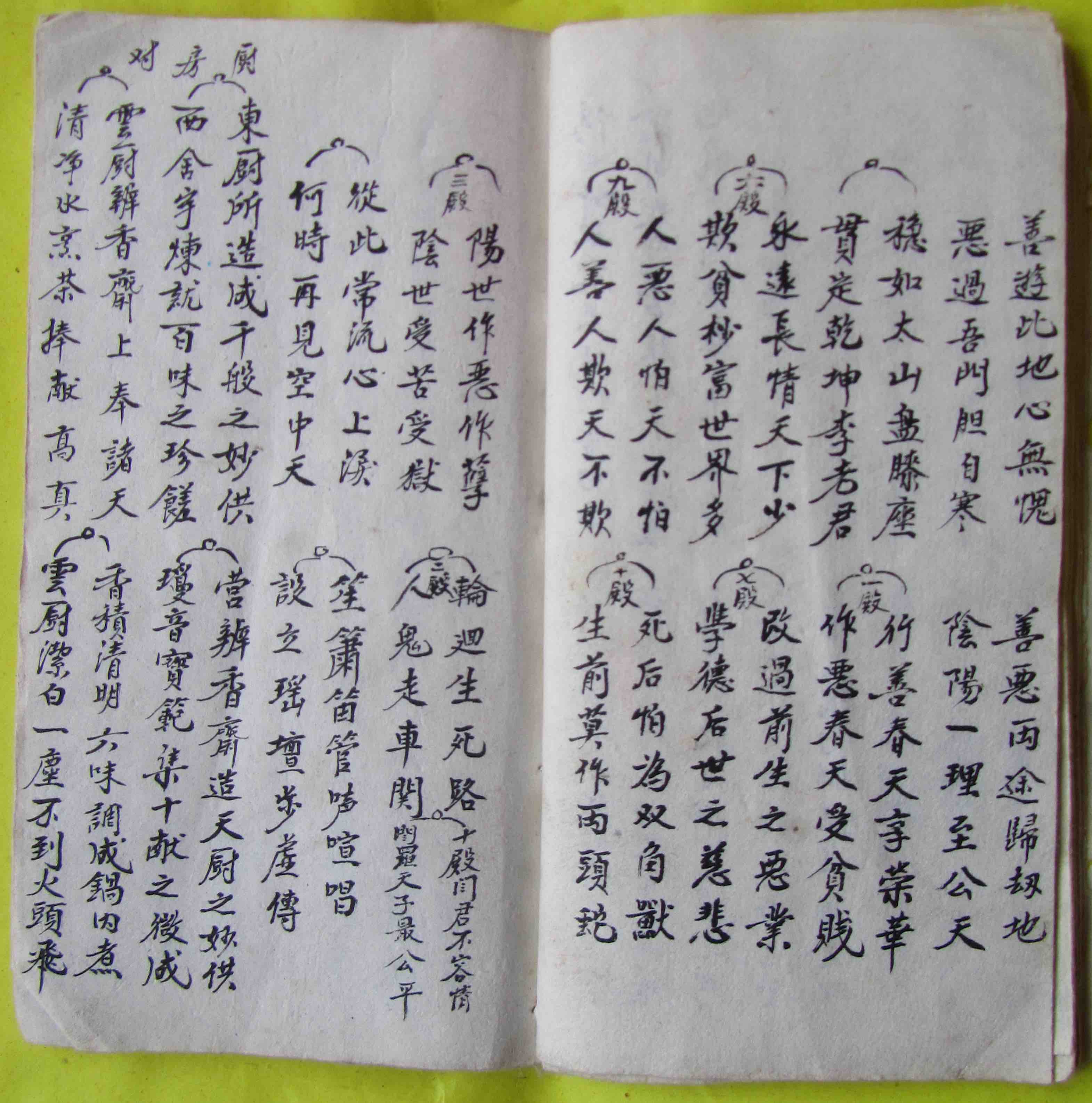

That first manual was not for one specific ritual segment, but a general-purpose collection of funerary texts. At 60 double pages, it is the second longest of all the manuals that he was to copy. Though giving a few texts for individual ritual segments, it is mainly a collection of shorter texts whose ritual use is not specified. Later Li Qing copied a similar compendium of texts for Thanking the Earth. These two compendiums suggest the practical basis of what the Daoists do: not long abstract texts, but individual lyrics to be adopted as required.

Similar collections of hymn texts, not specific to particular rituals, are found in early ritual collections within the Daoist Canon, and elsewhere among household groups in north and south China. Such volumes are often the most practical manuals for Daoists today. Li Qing’s hymn volume includes most of the texts that the Daoists need for the rituals they now perform. Many of the hymns, performed for both Delivering the Scriptures and the fashi public rituals, are not in any of the other ritual manuals, only in this separate volume.

However, looking more closely at the hymn volume, it is not merely a succinct practical list of texts for use in rituals, like those in the little notebooks that Daoists carry around with them. While it may be significant that this was the first volume that Li Qing wrote, he was apparently not compiling a new volume consisting of random texts recalled off the cuff, but copying out an existing one.

We need to exercise similar caution in studying the funeral compendium that Li Peisen copied, apparently before 1948. This manual is snappily entitled

Numinous Treasure Manual for Opening the Quarters, Summons, Reporting, Offering Viands, Roaming the Lotuses, Smashing the Hells, Dispatching the Pardon, Crossing the Bridges, Precautions against Hailstones, and Averting Plagues of Locusts

靈寶開方攝召預報獻饌游蓮破獄放赦渡橋祝白玉禳蝗瘟[科].

Here is another salient lesson in the importance of fieldwork and observation of practice. When Li Qing made his own copy in the 1980s, he divided it up into two volumes of 17 and 25 double pages. Perhaps he found the old manual too bulky (even the title is quite a mouthful)—he did copy more lengthy manuals, but this collection of rituals divided conveniently. Now imagine if we only had this manual, preserved in a library somewhere. If we were lucky enough to know that there was a Li family of whose collection it formed a part since the 1980s, we might suppose it was a faithful and rather complete description of the segments in their funeral practice, if not in the 1980s then perhaps in the 1930s. But we can’t use ritual manuals as a guide to performance. Until I began working more closely with Li Manshan, this single manual was almost my only clue to funeral practice as preserved in texts, and I found it bewilderingly irrelevant to their current practice.

Of the ten segments in the manual, only Opening the Quarters, the Pardon, and Crossing the Bridges were very occasionally performed in the 1980s; the others may well have been obsolete by the 1940s. The two rituals at the end (against hailstones and locusts) may have been not for funerals but for temple fairs. Moreover, the volume contains none of the standard segments of a funeral; some of those have their own separate manuals, but most have (and need) no manuals at all. And the texts of the seven visits to Deliver the Scriptures can be found only in the hymn volume—if you know where to look.

So one might suppose, “OK then, so Li Peisen’s manual shows the very different, more rigorous structure of funerals before the impoverishment since the 1950s.” That would be quite wrong! I now deduce that Li Peisen (or his forebears) put those ten rituals in a volume together precisely because they were rarely needed even before Liberation; it reveals not the then norm but the then exception. It doesn’t even quite match the “inner and outer five rituals”. Li Peisen’s generation may have been more able to perform these rarer rituals than either Li Qing or Li Manshan, but we mustn’t assume that the manual represents the standard practice of some ideal earlier age.

Apart from manuals for particular ritual segments (Invitation, Pardon, and so on), around half of the forty or so volumes handed down in the Li family are jing 經 “scriptures” or chan 懺 “litanies”. These have not been performed since the early 1960s, since they are not used for funerals or (at least in the current sequence) temple fairs, and Thanking the Earth is obsolete. They were mostly to be chanted fast rather than sung slowly.

The role of memory

Before we saw Li Peisen’s collection, Li Manshan claimed that Li Qing wrote many of the manuals on the basis of his memory. Blinkered by my background in Western art music, I was sceptical; and now that we have seen Li Peisen’s manuals, it does indeed begin to look as if they were mostly copying, not recalling. But a doubt nags. Li Peisen’s collection did include several old manuals, but I haven’t seen older originals for most of those that he and Li Qing wrote. So is it possible that memory did play a considerable role after all?

We may easily neglect the depth of folk memory—further afield, for instance (Tibet, the Balkans), epic singers might have huge unwritten repertoires. Chinese elites memorized vast passages of classical texts, as did the scions of the Li family both in private school and when learning the ritual manuals at home. Li Manshan, not easily impressed, is amazed to recall the knowledge, energy, and memory of the elders with whom he did rituals until the 1990s.

I can believe that Li Qing could recall the texts of rituals that he hadn’t performed much for a couple of decades; frequent practice since youth would have engraved them indelibly in his heart, and there are innumerable instances of this in China after the end of the Cultural Revolution. Li Qing’s perceptive granddaughter Li Min points out that he loved the scriptures so much, he would always have been reciting them silently in his heart, even in periods of forced silence like his sojourn in the troupe or the Cultural Revolution. He performed them almost daily from 1932 to 1953, less from 1954 to 1957, not from 1958 to 1961, then from 1962 to 1964, but not from 1964 to 1979. Was that enough? In many cases I now tend to think it was, but it would depend on the scripture; some of them he would hardly have performed since 1953. Li Peisen, sixteen years Li Qing’s senior, had even longer experience. Also, the degree of serial repetition in Daoist texts is such that one could recreate a lot just by filling in the titles of a series of gods and offerings, much of the remaining content being identical for whole long series of invocations. Where phrases are of regular length, that would give further clues.

I supposed that the lengthy scriptures chanted fast to the regular beat of the muyu woodblock might be hardest to recall, especially since these were the only ones that they recited with the manuals on the table in front of them. But even these, Li Manshan observes, they largely knew by heart—Kang Ren whipped through them so fast that he couldn’t keep up; he hardly referred to the manual at all, just turning the pages as a backup.

And how about a lengthy and complex manual like the Lingbao hongyi shishi quanbu? I would be amazed if Li Qing could have rewritten it from memory having hardly performed it since at least 1957, but Li Manshan points out that by then his father would have taken part in the ritual often enough for over twenty years. I still demur: how often would that have been, actually? It was only performed for three-day funerals, and even there it was an alternative to Hoisting the Pennant and Judgment and Alms.

And surely it is one thing to recite such scriptures from memory, another to commit them to paper without frequent miswritings. Li Qing’s manuals contain few corrections—only occasionally do we find an extra character or line in black or red added between the columns where he had accidentally omitted it, or slips of paper pasted over a short passage that he later realized was inaccurate. And characters are rarely miswritten. Folk transmission over a long period often produced minor variants, but in general the texts are written meticulously, and where we can collate them with the manuals of the great temples they are basically identical.

Sharing manuals

One sweet vignette offers a glimpse of the energy for copying scriptures in the 1980s. Li Peisen’s disciple Kang Ren evidently copied many of his manuals too, perhaps after Li Peisen’s death in 1985. He borrowed the Lingbao hongyi shishi quanbu manual from Li Peisen’s son Li Hua, but when he took it back Li Hua was out, so on its back cover he wrote him a message to ask for four more manuals:

Younger brother Li Hua, can you bring me the Xianwu ke, the Shenwen ke, the Dongxuan jing, and the Shiyi yao? Please please!

As it turned out, none of those scriptures would be performed again; like Li Peisen and Li Qing, Kang Ren was just being enthusiastic, excited at the potential for restoring the scriptures that they had all recited constantly throughout his youth, after a long silence.

Kang Ren’s access to the manuals was exceptional. They were generally transmitted only within the family, not widely shared among disciples, even within Li Qing’s group. Daoist families are always in competition, and while they may often collaborate for rituals, there is an innate conservatism about revealing the core of a family heritage. Apart from the few manuals that they needed to consult while performing rituals, some of Li Qing’s senior colleagues from other lineages might never see them. When Golden Noble and Wu Mei were learning in the 1990s they hardly got to see the manuals; Li Qing wrote them individual hymns on slips of paper one at a time, just as Li Manshan did more recently for his pupil Wang Ding. Li Qing lent his manuals to the Daoists of West Shuangzhai in the 1980s so they could copy them, but in general there was little borrowing between rival Daoist families, even those on good terms. But the ritual tradition is remarkably oral.

However, Kang Ren, as well as Li Yuanmao (whose father was a Daoist anyway), copied manuals too. If any of their scriptures survive, they would be copied from Li Peisen. But since Kang Ren’s death in 2010 his son has sold them, and Li Yuanmao’s son is cagey.

The identity of the copyists

As we saw, the bulk of the two surviving collections was copied in the early 1980s by Li Peisen and Li Qing, as well as some earlier manuals written by their forebears. Manuals are almost always signed, usually on the cover, sometimes also at the end.

The earliest manuals we have now were written by Li Xianrong around 1900. We have clues to manuals by his younger brother Li Zengrong. And we have one manual said to be in the hand of their cousin Li Derong, as well as his precious early score of the “holy pieces” of the shengguan music. For a genealogy, see Daoist priests of the Li family, p.5; for the family’s own genalogies, see photos here; note the alternation by generation of single- and double-character given names.

Li Xianrong’s second and third sons Li Shi and Li Tang both copied manuals. Li Shi’s manuals were among those that his grandson Li Qing sacrificed in 1966, but Li Peisen preserved those of his father Li Tang, two of which are still in Li Hua’s collection. Li Peisen himself wrote many manuals. So did his cousin Li Peiye (1891–1980)—but his son Li Xiang took them off when he migrated to Inner Mongolia in 1959.

Authorship may not be quite so simple. Li Qing wrote his own name on the cover page, almost always adding the character ji 記, “recorded by.” But in some cases a father would write a manual for his son, writing the son’s name on the cover—again, almost always with the character ji, in this case meaning “recorded for.” For instance, most of Li Peisen’s manuals from the early 1980s bear the name of his son Li Hua; Li Qing only wrote Li Manshan’s name on one manual, the Treasury Document and Diverse Texts for Rituals, written in 1983 or soon after; and on the cover of Li Manshan’s only manual he wrote the name of his son Li Bin. When there is a name at the end of the manual, it is that of the copyist himself. Most earlier manuals (Li Xianrong, Li Tang, and so on) were signed by the copyists themselves.

Why did Li Peisen often write his son’s name, whereas Li Qing almost always wrote his own name? It wasn’t so much that Li Qing still saw Li Manshan’s future mainly in determining the date, but that he had two other sons who were potential Daoists, so perhaps he was avoiding favoritism. Of Li Peisen’s two sons, the older, Li Huan, was only going to specialize in determining the date; but Li Peisen must by now have earmarked his second son Li Hua (30 sui in 1980) as a Daoist. Perhaps a more pressing reason was that Li Peisen was getting on in years, and wanted to feel he was leaving his manuals for posterity, whereas Li Qing was still only in his mid-50s.

Anyway, it’s worth bearing in mind that a manual bearing someone’s name may have been copied by his father. Expertise in calligraphy may help, but it takes me time even to distinguish the calligraphy of Li Peisen and Li Qing—Li Peisen’s brush ever so slightly more cursive, Li Qing’s more bold. The styles of Li Qing and Kang Ren were virtually identical.

The manuals of Li Xianrong

I have only seen four manuals by Li Xianrong, most written in the early 20th century, when he was around 50: in Li Hua’s collection, Lingbao shiwang guandeng ke (1901), Lingbao shanggong ke, and probably Lingbao hongyi shishi quanbu (1912); and in Li Manshan’s collection, the Lingbao jinbiao kefan (see above). Li Hua claims to recall two whole trunks of scriptures by Li Xianrong, but says that only a quarter now survive. If so, then he hasn’t shown us all of them—and if Li Peisen didn’t have to sacrifice them, then why have so many been lost since?

Li Xianrong’s “style” (zi) or literary name was Shengchun, only used in one manual that I have seen, the Lingbao shiwang guandeng ke. The very fact that he had a literary name suggests his superior social status. He wrote in a more elegant hand than either Li Peisen or Li Qing; Kang Ren liked to consult his scriptures.

Li Peisen’s own manuals

The manuals that Li Peisen inscribed for his son Li Hua (b.1951) are evidently the new copies he made from around 1980 after returning to Upper Liangyuan. He wrote some manuals earlier, but it is hard to guess when; even if Yang Pagoda was quite undisturbed under Maoism, it seems unlikely that he wrote any over that period. He was only 39 sui in 1948, perhaps a bit young to write manuals before then, but he evidently did so. He was also known as Li Peisheng, the name he wrote at the end of the Yushu chan.

The Lingbao shiwang bawang dengke is one of the earlier manuals bearing Li Peisen’s name on the cover. It is dated on the last page with the inscription

23rd year of the Republic [1944], 6th moon, 3rd and 4th days,

Bingshan picked up the pen to finish copying.

Indeed, this page doesn’t look like Li Peisen’s hand. No-one can be sure who Bingshan was—there was one in Xingyuan village, but he was only born in the 1920s; was there another one? And why did Li Peisen hand it over to Bingshan to complete? Perhaps he got busy with his work as village chief—but why ask someone from another family (presumably a disciple) to complete it, rather than shelve it until he had time? Did they need it in a hurry for a funeral? This was one manual that they did need to follow from at least two copies while performing it.

The couplet volume

Among the volumes that Li Qing copied in the early 1980s is a collection of 21 double pages listing around 300 matching couplets (duilian, see Daoist priests of the Li family, Ritual 7) to be pasted at either side of a doorway or god image. Such volumes are often part of both temple and household collections. Again, this one is evidently copied (or edited) from an earlier volume. Perhaps it originates from a temple, since many of the contexts listed seem unlikely to have been part of the Li family tradition even before the 1950s.

Temple collections often list couplets for particular types of temples, and Li Qing’s volume has some for particular deities—though not for those of the Upper Liangyuan temples, nor for any local gods like Elder Hu. Most are single couplets, but there are over thirty for the Dragon Kings (Longwang). There are eight for the God Palace (Fodian)—not necessarily for the village’s own Temple of the God Palace.

A couplet for the “meditation hall” (chantang) further suggests the temple connection, as do couplets for bell tower (zhonglou) and several for the opera stage (xitai). But I can’t be sure if this implies an earlier derivation from temple priests, or simply that couplets were required for the unstaffed temples of the area when they held temple fairs. There are twenty-two couplets for the scripture hall, and fourteen for the kitchen. There are couplets for each of the Palaces of the Ten Kings, perhaps to adorn existing paintings or murals, and fifty couplets for Thanking the Earth. There are verses for each of the “seven sevens” after a death, the hundredth day, and for all three anniversaries, and over fifty couplets for the burial itself.

Couplets for the scripture hall, including series for the Ten Kings.

There is a couplet for seeking rain, and fourteen for raising the roofbeam. There are many for more general social life, such as those for archways, cattle sheds, and carts; for carpenters and metal workers, and for the “wine bureau” and pharmacy. Six further verses marked “treasury couplets” are for the funerary treasuries. The volume opens with a series of over twenty couplets for weddings, the only instance of any Daoist component for this context.

Near the end of the volume there is a series of four-character mottos—the diaolian large paper squares to be hung on the lintel where the coffin is lodged. Li Manshan has to write these regularly for funerals, but again he never needs to consult the volume: he’s been writing them from memory for over thirty years.

In all, the couplet volume suggests how pervasive Daoism was in the daily life of a previous era, but we can’t deduce how many of these couplets Li Qing or even Li Xianrong commonly used.

The fate of the new manuals

Despite all this energy in recopying, once Li Qing and his colleagues began performing ritual again, few of the segments that require the use of the manuals were to be restored in practice.

Most rituals in common use for funerals consisted of relatively short texts that could be memorized. When the manuals are needed, it is mainly for rituals that are rarely performed; and until the early 1960s, they would also have been used for the lengthy fast recited chanted scriptures that were part of temple and earth rituals, like Bafang zhou and Laojun jing. Li Peisen and Li Qing devoted considerable energy to recopying these chanted scriptures, but their optimism that they would be restored in performance under the new more liberal conditions turned out to be misplaced. So while we may treasure the manuals that they copied in the early 1980s (not least since they provide clues to former practice), we must observe that after they had been copied they were hardly consulted.

Notebooks

More prosaically, Daoists now often transcribe the texts they need into little exercise books, copying them horizontally in biro. For the sinologist they may seem unpromising: small, with plastic covers (a welcome innovation with regard to preservation), sometimes bearing cheesy pinup-type photos. Through the 1990s I myself had something of a fetish for using such kitsch notebooks for my fieldnotes, but eventually I resigned myself to the posher ones that had replaced them in the shops. But such notebooks copied since the 1980s are an important resource. They are probably the most useful guide to their current practice, even if their older manuals, elegantly copied with brush and ink, look more elegant and archaic. Household Daoists in Shuozhou county nearby have copied some long complete ritual manuals into such notebooks. Apart from convenience, after the traumas of recent times, perhaps Daoists also took instinctively to small easily-stashed notebooks, rather than more bulky old tomes.

Like all men who determine the date, Li Manshan has several small notebooks that serve as almanacs for all his complex calendrical calculations. But sometime in the 1990s he copied a little blue notebook in the traditional vertical style, with a set of ritual texts densely written over twenty-five pages. Later he wrote a black notebook with a mere fifteen texts in 21 pages, this time copied horizontally. This briefer volume may now meet most of his needs for funerals, such as Delivering the Scriptures and Transferring Offerings, but it by no means shows the full extent of his recent practice; he still performs many texts not copied there. And some of them don’t even appear in Li Qing’s lengthy hymn volume. Li Manshan may have written his blue notebook to remind him of the texts, but the black one served a different purpose (as he says, “I don’t need them, they’re in my belly”)—“Because if someone tells me I’m making it up as I go along, I can take it out and show him it’s the real deal!” So it wasn’t an aid to memory so much as a kind of certificate, almost like a license.

Li Manshan recalls that Li Qing had a similar notebook for various such texts, which we haven’t found. Did Daoists always use something similar? Of course, the beauty of the Mao jacket is that it can store such a notebook. When did notebooks become available in Yanggao? Going back through imperial history, what kind of equivalents might Daoists have used? And, if you’ll allow me a further sartorial query, what kind of pockets would they have put them in?

Perhaps the Dunhuang religious manuscripts from around the 10th century offer a clue. They include some small booklets, “the size of a pack of Lucky Strikes”, as Teiser describes them, going on to speculate nicely: “Easily transported? Hidden in a sleeve? Used surreptitiously? Studied in private?” As he remarks, “a booklet this size would serve as a perfect study guide for an officiating priest.” But with our experience now, we would wish to unpack a term like “study guide”.

* * *

In my book I go on to explore the ancestry of the texts contained in the ritual manuals. This bears on the complex issue of the relation between Orthodox Unity and Complete Perfection (for an outline, see here).

Some scholars have traced rituals still practiced in Jiangnan or south China to early, whole, ritual manuals in the Daoist Canon. At least in north China, this is unlikely to be at all common. Few of the texts sung there by modern household and temple Daoists appear in such early sources; many can only be documented since the late imperial period. Such a conclusion may help us modify an antiquarian tendency in Daoist studies.

All this suggests merely that these texts are part of a broad tradition related to modern temple practice. And since many of them are common to household groups over a wide area of north China, we have to take the temple link seriously. Even poor household Daoists, quite remote from urban elite traditions, with no clues in their oral history to any temple connection, turn out to have a substantial link to the nationally promulgated texts of the major temples. We can only guess at the ritual repertoires of smaller regional temples that were the links between the major temples and rural household groups.

Still, having traced a few isolated texts, it is frustrating that parallels with most of the ritual manuals remain elusive, like Communicating the Lanterns or Dispatching the Pardon (see my book, ch.13). Such repertoires look like a patchwork assembled from various sources, few of which may ever emerge. We have a few pieces of a few jigsaws, and none at all for others.

So in a ritual corpus like this we have three types of text, some highly standard and national, others apparently distinctive and regional, even local:

- Ritual manuals: now hardly performed; few sources in the Daoist Canon or elsewhere, either whole or in part.

- Individual hymns still in use today: few appear in the Canon, but many are found in modern temple sources like the daily services and yankou—which are now known mainly in Complete Perfection versions.

- Scriptures: no longer performed; nationally standard, ancient, and found in both the Daoist Canon and modern temple sources.

The contrast between ritual manuals and scriptures is absolute. The scriptures, “in general circulation,” can easily be found in the Daoist Canon, their titles and contents identical. But the ritual manuals can’t be found—neither their titles nor the great bulk of individual texts within them. However, many of the individual hymns, as well as scriptures, are common with the current practice of temple priests, who happen to be Complete Perfection—notably those found in the Xuanmen risong and yankou. This doesn’t mean that the Li family tradition is or was mainly based on them, since the great bulk of the other texts in the ritual manuals cannot be traced; but the fact that “standard” temple Complete Perfection texts are the single most fruitful match with the Li family’s current repertoire should remind us that the superficial dichotomy of “folk Orthodox Unity versus temple Complete Perfection” is a mere academic fantasy.

* * *

So we do indeed need to document ritual manuals, but it is performance that is primary. Daoists aren’t dependent on the manuals, relying on much knowledge that can’t be reflected in them; so rather than being the main object of study, they should be an adjunct to our study of changing performance practice.

While it is with the Li family that I collected most ritual manuals, for other such texts see the many pages under Shanxi and Hebei in the Menu.

[1] For fine accounts of the whole process in south Fujian, see Kenneth Dean, “Funerals in Fujian” Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 4 (1988) and his Taoist ritual and popular cults of southeast China (1993).

[2] With the study of ritual manuals dominated by south China, the general term keyiben 科儀本 has become standard in scholarship. I don’t know if this term is commonly used by southern Daoists, but it isn’t heard in the north. In Hebei they often refer to ritual manuals as jingjuan, but in north Shanxi the more prosaic term is jingshu or jingben, or even the innocent-sounding shu “books.” Since manual titles often end with the term keyi, they could notionally call those manuals “keyiben”—but they don’t. For such vocabulary, see here.

[3] Cf. amateur ritual associations in Hebei, where many manuals were copied in the short-lived restoration of the early 1960s: see Zhang Zhentao, Yinyuehui, pp.67–396, and many posts under Hebei in the main Menu.

[4] For the production of early Ten Kings scrolls from Dunhuang, see Stephen Teiser, The Scripture of the Ten Kings and the making of purgatory in medieval Buddhism (1994), pp.88–90, 94–101. 16 or 17 characters per line seems common down the ages, but the number of lines per page is variable—some modern printed scriptures produced by the Baiyunguan in Beijing have only 5 lines per page (half of a folded page of 10 lines).

The Wanhe tang:

The Wanhe tang:

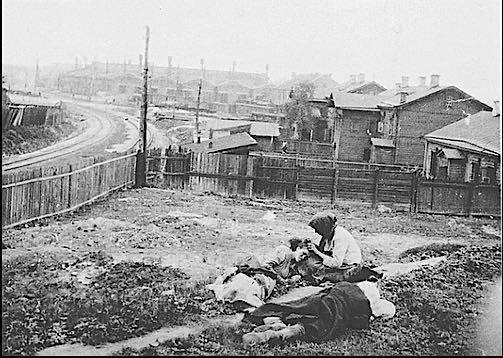

Exiles in a “special settlement” in western Siberia, 1933.

Exiles in a “special settlement” in western Siberia, 1933. “Kulaks” exiled from the village of Udachne, Khryshyne (Ukraine), early 1930s.

“Kulaks” exiled from the village of Udachne, Khryshyne (Ukraine), early 1930s. Yevdokiia and Nikolai with their son Aleksei Golovin (1940s).

Yevdokiia and Nikolai with their son Aleksei Golovin (1940s).

Nikolai Kondratiev’s last letter to his daughter, 1938.

Nikolai Kondratiev’s last letter to his daughter, 1938. Elena Lebedeva with her granddaughters, Natalia (left) and Elena Konstantinova,

Elena Lebedeva with her granddaughters, Natalia (left) and Elena Konstantinova, Left: Zinaida Bushueva with her brothers, 1936.

Left: Zinaida Bushueva with her brothers, 1936.

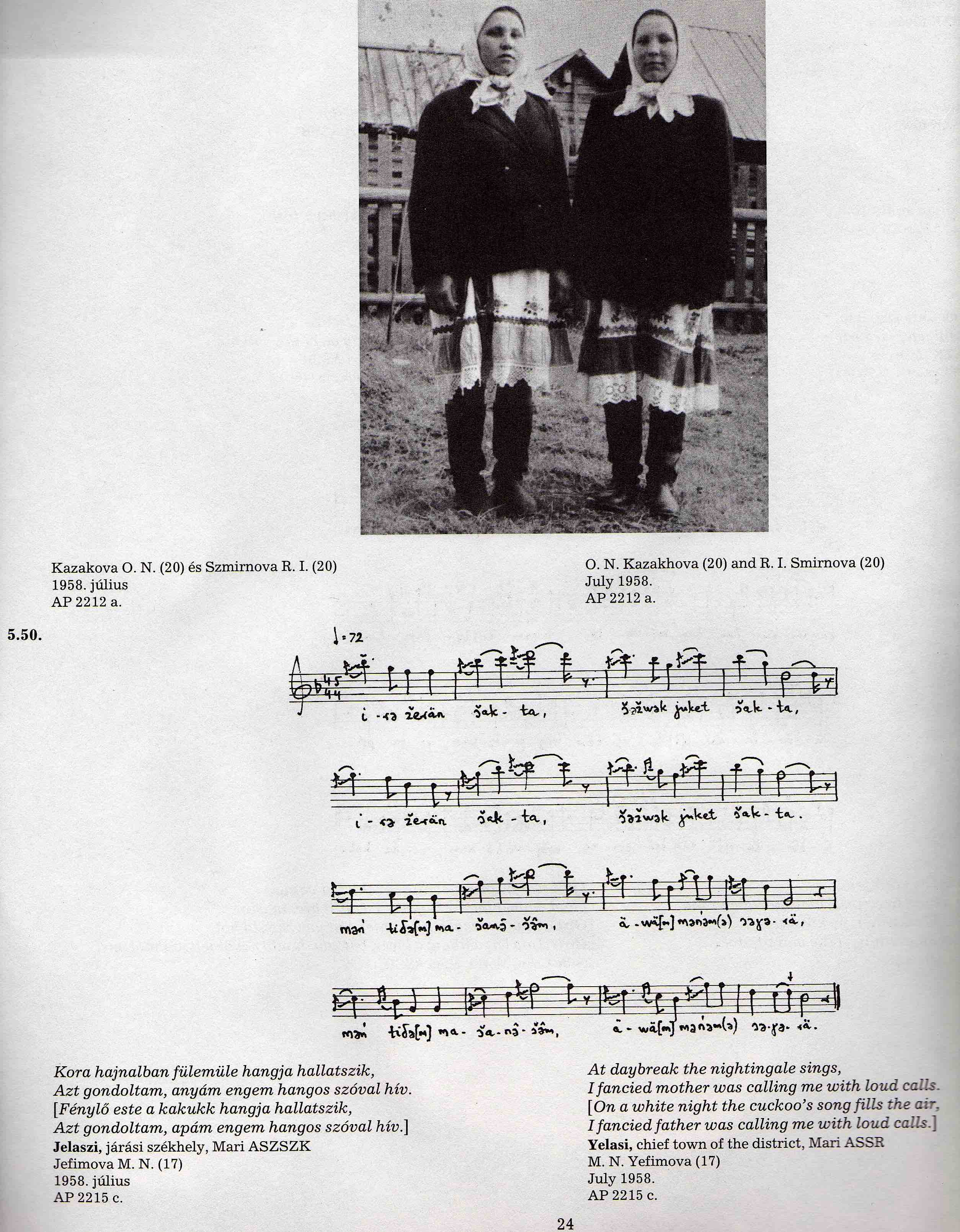

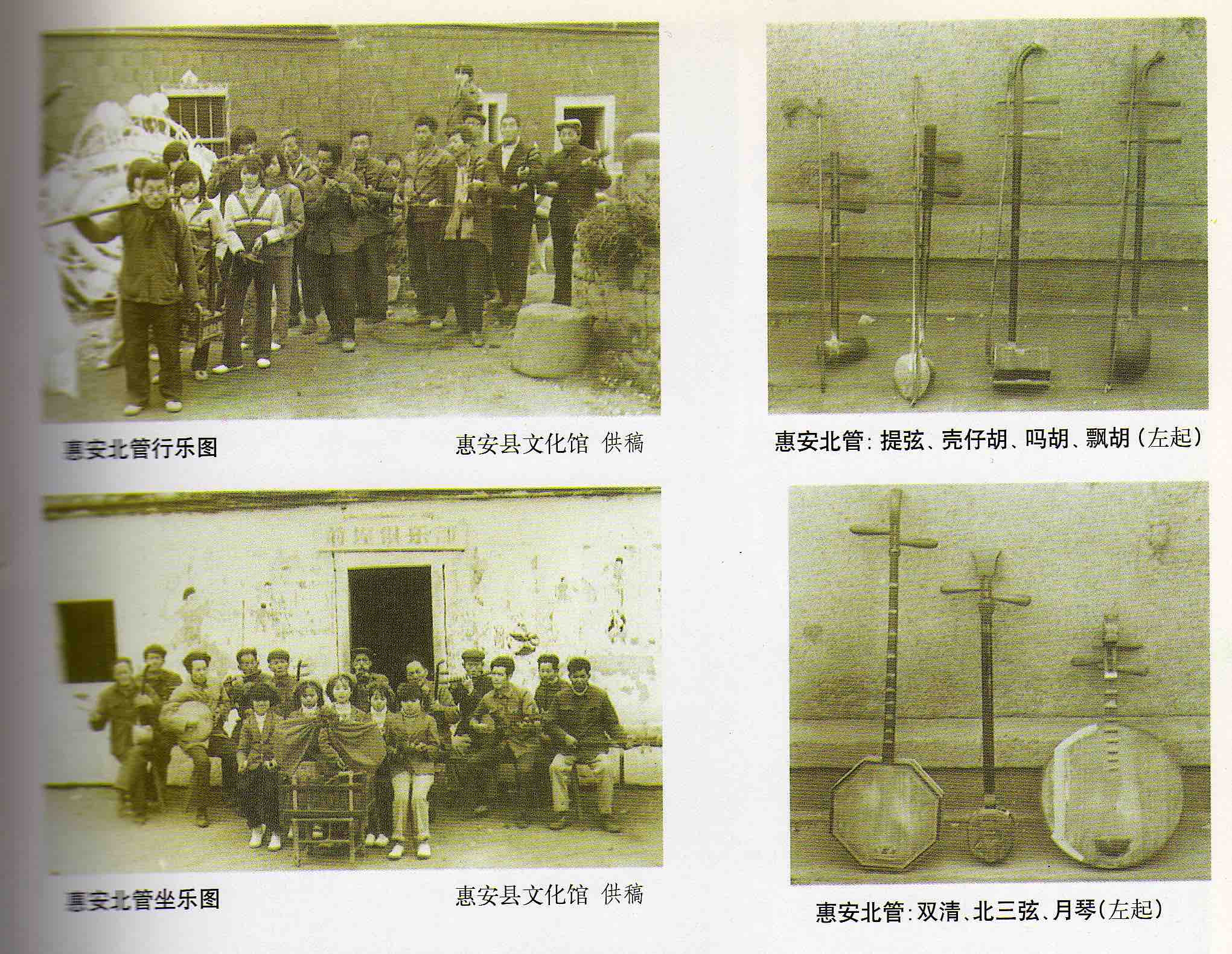

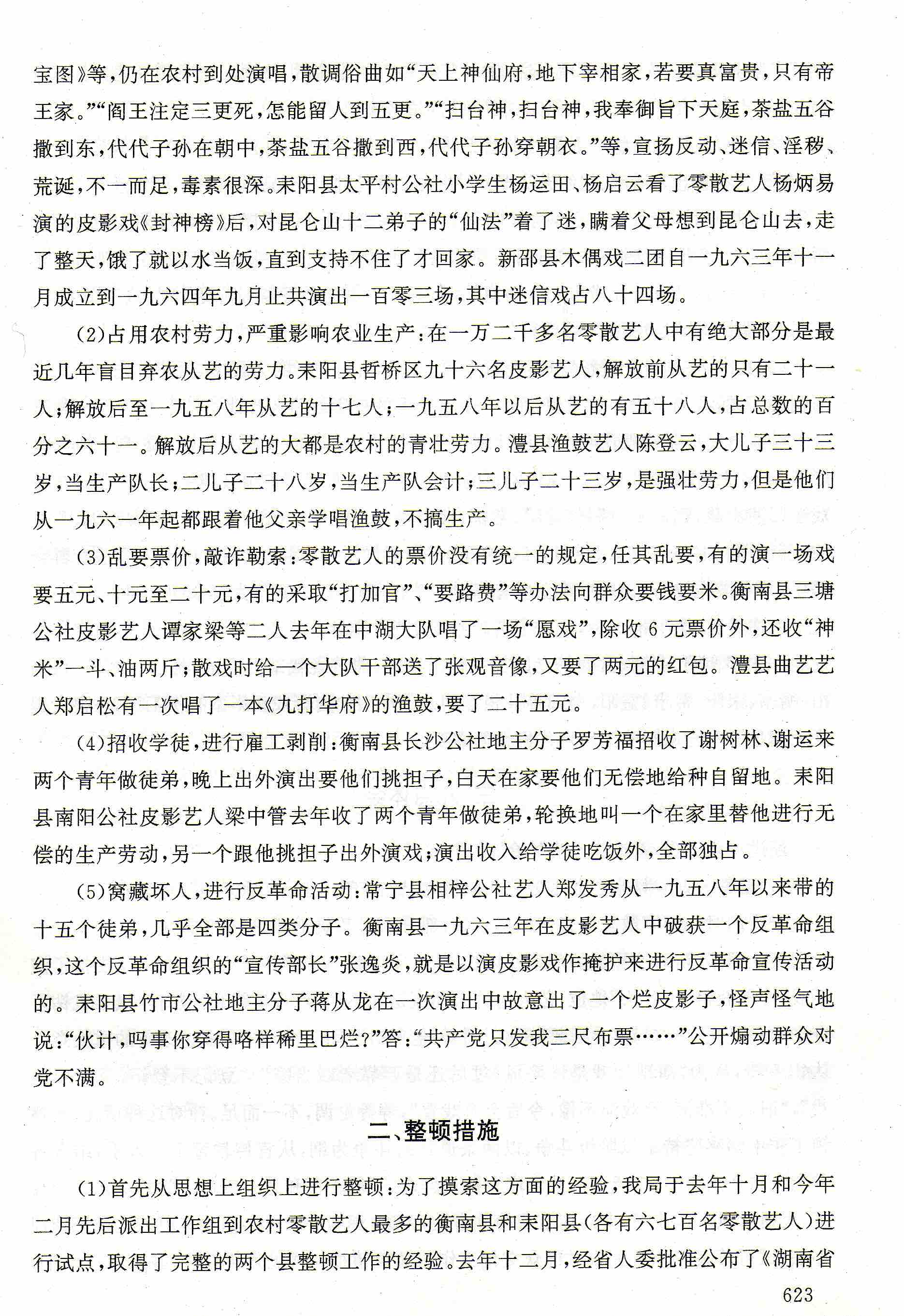

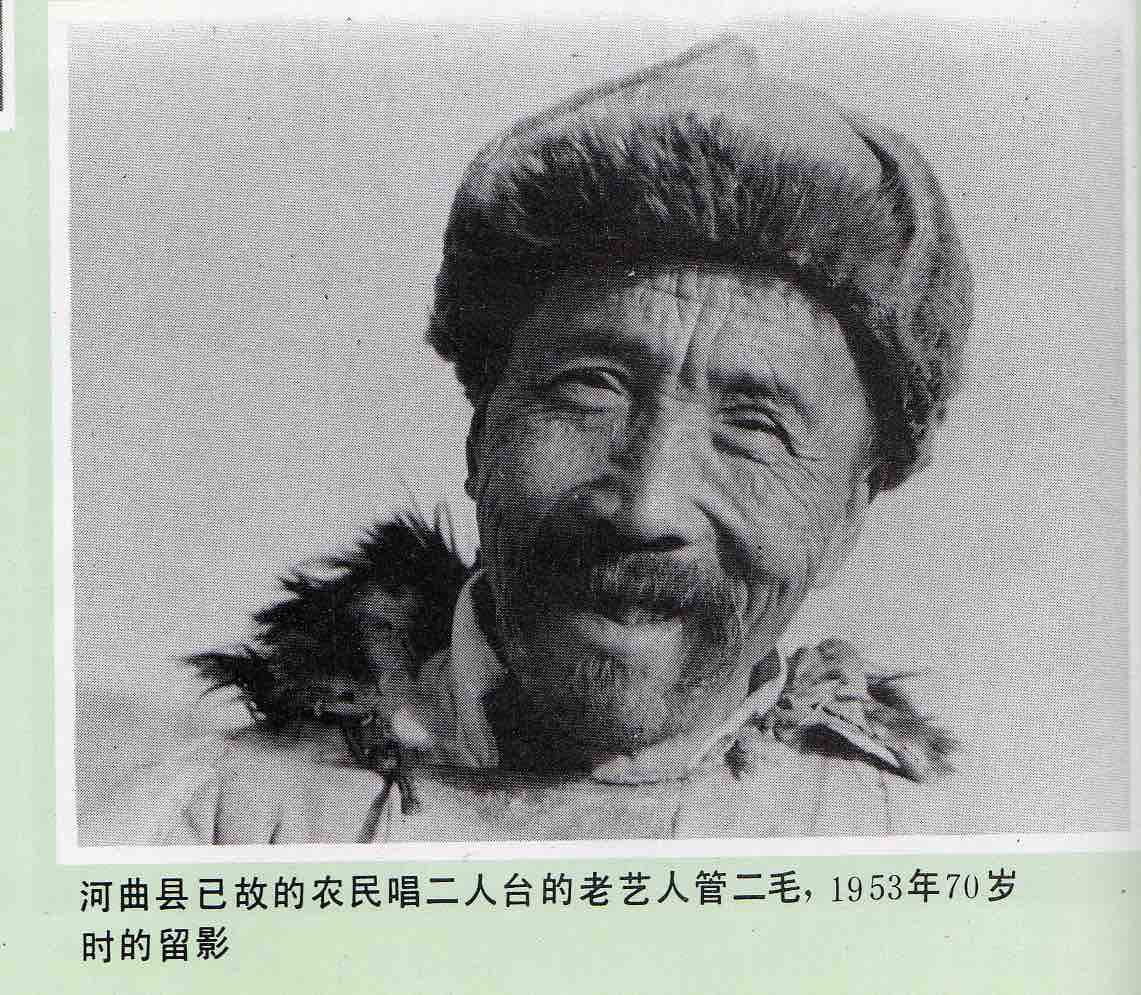

To accompany my new post outlining diverse performance genres of

To accompany my new post outlining diverse performance genres of

After

After

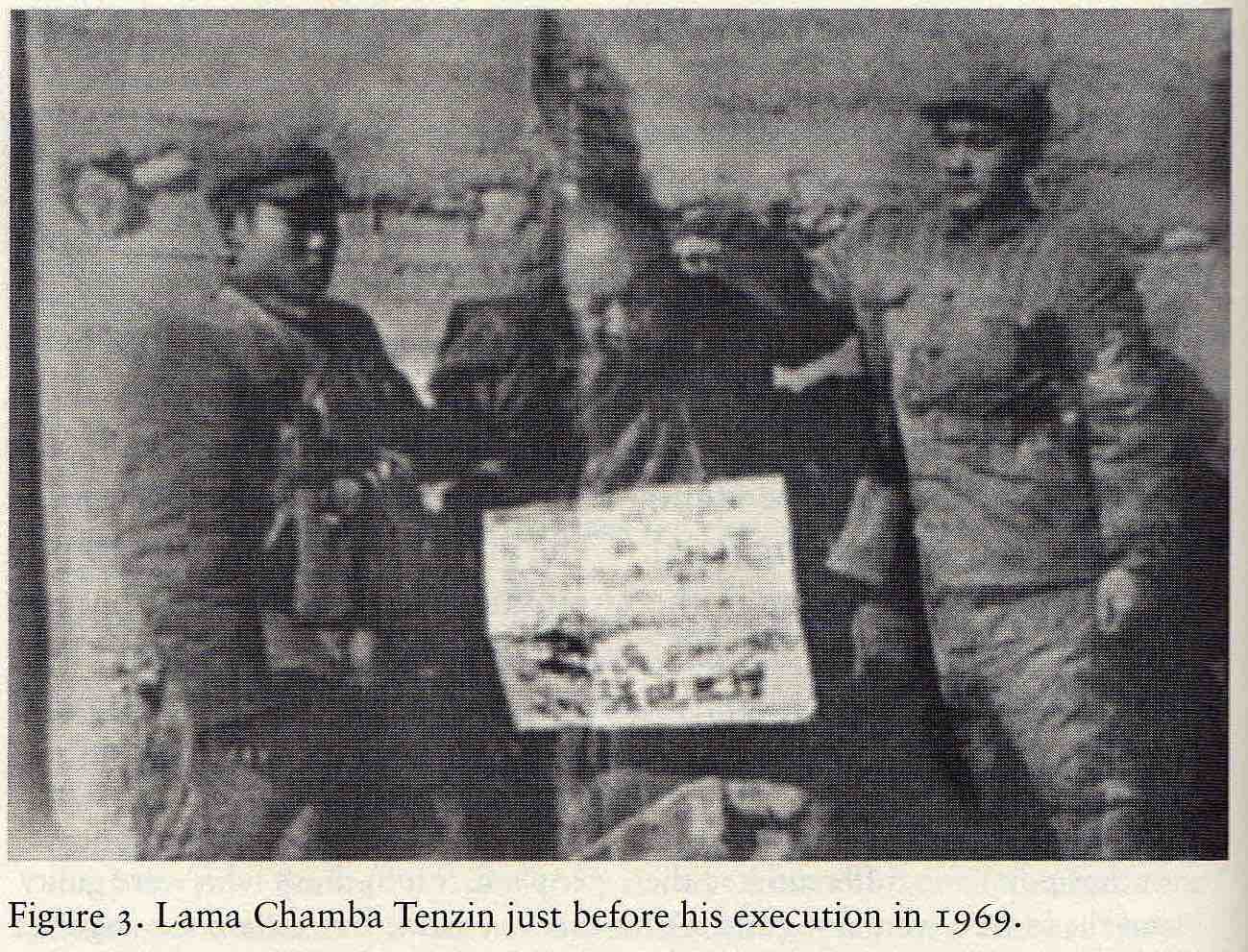

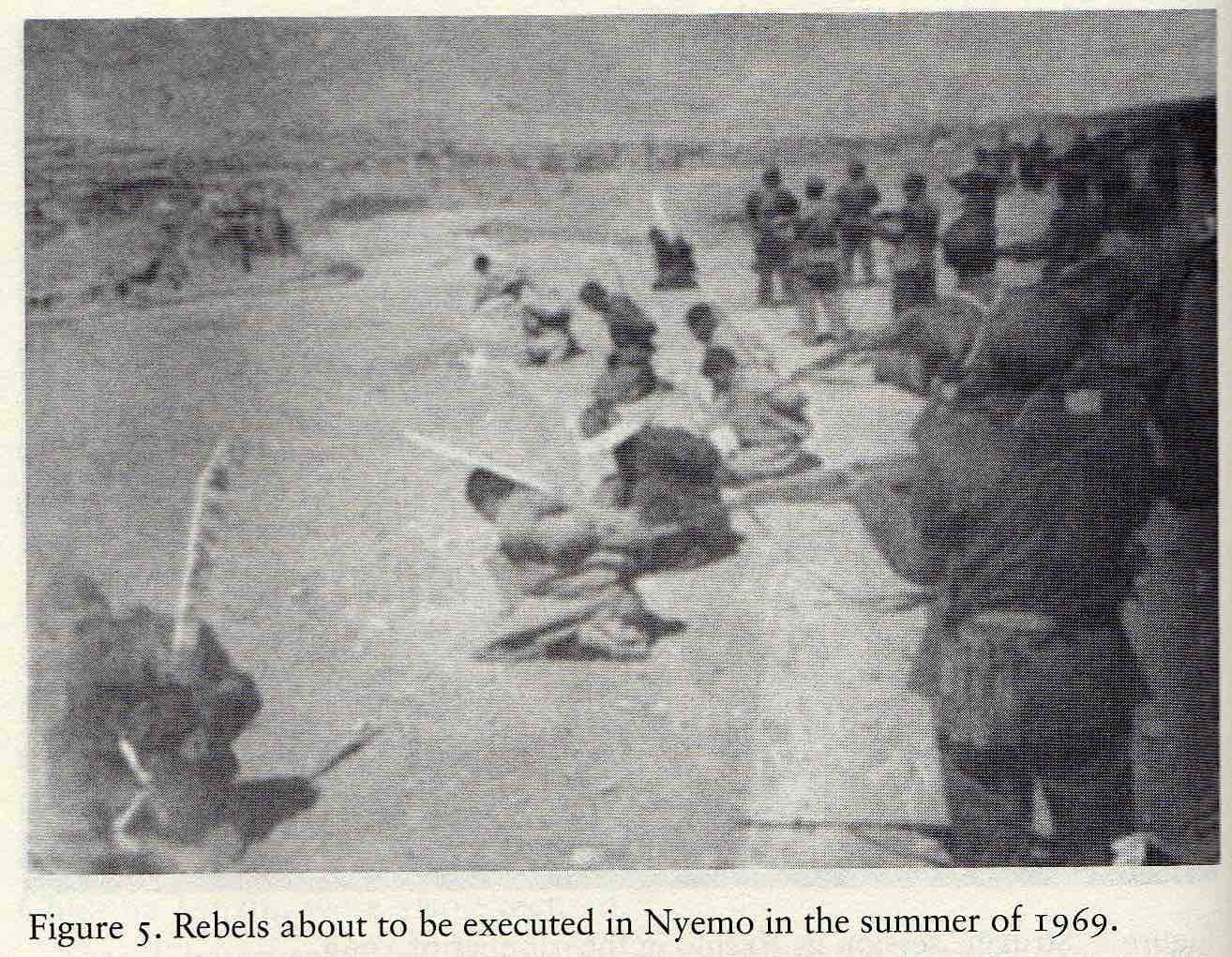

The authors seek to assure the reliability of interviews by collating a wide range of accounts (including but not limited to interrogations and confessions), from victims and perpetrators, members of both factions, ordinary people caught up in the events, officials and soldiers.

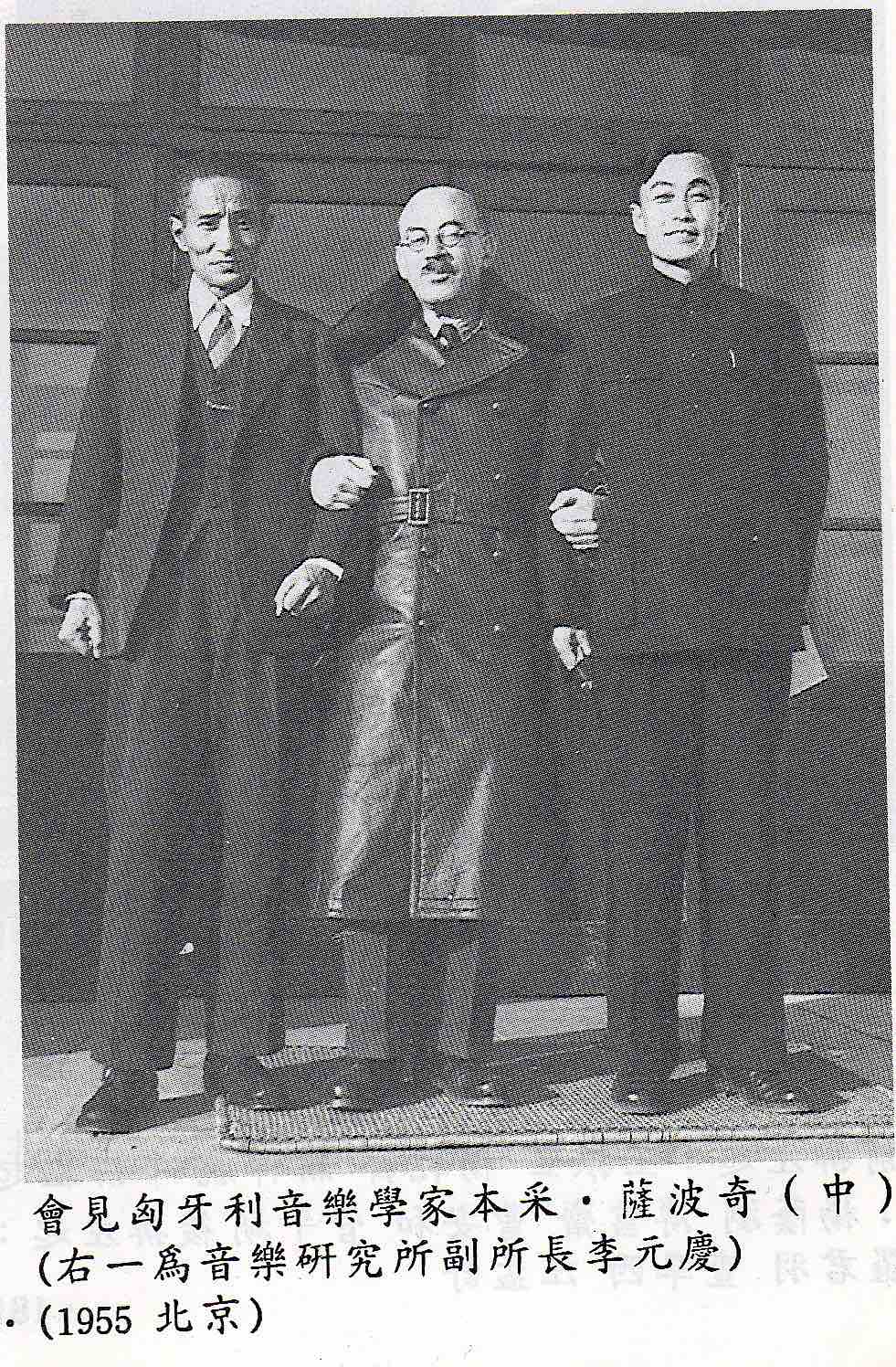

The authors seek to assure the reliability of interviews by collating a wide range of accounts (including but not limited to interrogations and confessions), from victims and perpetrators, members of both factions, ordinary people caught up in the events, officials and soldiers.