*Part of my extensive series on Tibet*

- Keila Diehl, Echoes from Dharamsala: music in the life of a Tibetan refugee community (2002)

is the fruit of ten months that the author spent from 1994 to 1995 in the hillside capital of the Tibetan government-in-exile in northwest India, “perched in the middle of one of the world’s political hotspots”. Despite the presence of the revered Dalai Lama, Dharamsala is no mystical paradise.

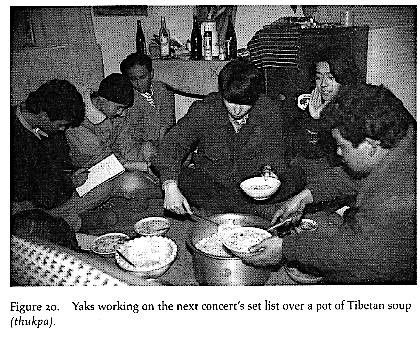

As Diehl explains in the Introduction, Dharamsala felt somewhat over-subscribed as a topic, and she had hoped to study Tibetan refugee communities elsewhere in India; but she was drawn back there by circumstance, and soon became a participant observer playing keyboards with The Yak Band. This informs her thesis on the performance and reception of popular music and song by Tibetan refugees—including traditional folk genres, Tibetan songs perceived as “Chinese”, Hindi film songs, Western rock, reggae, and blues, new Tibetan music, and Nepali folk and pop.

In the Introduction she notes a contradiction between scholarship on displacement and the people whose experiences generated it. Whereas anthropological theory tends to celebrate “transgression, displacement, innovation, resistance, and hybridity”,

it became clear that many of the displaced people I had chosen to live among and work with were, in fact, striving heartily for emplacement, cultural preservation, and ethnic purity, even though keeping these dreams alive also meant consciously keeping alive the pain and loss inherent in the exile experience rather than letting or helping these wounds heal.

Further, much of the scholarship that does include ethnographic case studies tends to emphasise

the richness, multivocality, dialogism, and creativity of their subjects rather than their deep conservatism, xenophobia, and dreams of emplacement.

Diehl gives cogent answers, in turn, to “Why study refugees?”, “Why refugee music?”, “Why refugee youth?”, and “Why Tibetans?”. Exploring “zones of invisibility” (and inaudibility), she seeks to

fill in some of the gaps left by the many idealised accounts of Tibetans. Through its generally uncomplicated celebration of political solidarity and cultural preservation in exile, much of the available information on Tibetan refugees exhibits a troubling collusion with the community’s own idealised self-image. […]

After four decades in exile, many Tibetans realise not only that the utopian dream is still an important source of hope but also that it can be a source of disappointment and frustration that has very real effects on individuals and communities who are raised to feel responsible for its actual, though unlikely, realisation.

She introduces the “Shangri-La trope”, analysed by Bishop, Lopez, and Schell, and notes the “disciplinary bias within Tibetan Studies towards the monastic culture of pre-1950 Tibet”—a bias that applied also to Tibetan music, largely interpreted as “Buddhist ritual music” until the mid-1970s (cf. Labrang 1). Since Diehl wrote the book, the whole field has been transformed by new generations of scholars at last able to document Tibetan culture within the PRC.

She notes Dharamsala’s position at the “literal yet liminal intersection” of a “geographical and conceptual mandala”:

What complicates this apparently cut-and-dry native point of view is the fact that […] sounds and musical boundaries are, ultimately, immaterial and are therefore felt and experienced in personal and varied ways.

Chapter 1, “Dharamsala: a resting place to pass through”, depicts the town as both a centre and a limen, a destination for pilgrimage which refugees hope eventually to leave. Besides them, the ever-shifting population also includes civil servants, nomads, traders, aid workers, dharma students, and tourists.

Members of the oldest generation in exile came to India from Nepal, Bhutan, or India’s North East Frontier Area (now Arunachal Pradesh) after escaping from Tibet in 1959 on foot over the Himalayas, travelling in family groups under the cover of darkness, following their leader into exile. Since then, for forty years, Tibetans have continued to escape from their homeland in a procession whose flow varies with the seasonal weather, the attentiveness of Nepali border patrols, the effects of specific Chinese policies in Tibet, and the varying intensity with which these policies are implemented in different regions of the country and different times.

Diehl identifies three general waves of migration:

The first escapees (between 1959 and the mid-1960s) came from Lhasa, Tingri, or other southern border areas of the country. Few Tibetans escaped during the worst years of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), but in the 1980s a second wave of refugees, a number of whom had been imprisoned during the first decades of Tibet’s occupation, fled Tibet. Since the early 1990s, a third wave of refugees from Amdo in the northeast, known as sar jorpa (“new arrivals”), have arrived in exile, putting the greatest demands on the government-in-exile’s resources and institutions since the first months spent establishing tent camps, clinics, and schools in 1959.

Besides regional aspects, I note that there are political and class considerations here too, as the old generation that included aristocrats and former monks from the Lhasa region was replaced by commoners (and former monks) from a wider area, brought up under the routine degradations of de facto Chinese occupation. At first the shared plight of exile tended to homogenise interactions:

It was irrelevant, even laughable, to insist on special privileges or respect because one’s father had been a regional chieftain in Tibet, when you had no more power to set foot in Tibet than your neighbour, the son of a petty trader from Lhasa.

But social, regional, and sectarian divisions later re-emerged.

Some refugees in the diaspora avoid Dharamsala altogether, specifically because of the ambition, materialism, self-consciousness, and conservatism engendered by its status as an international hub of activism, tourism, and bureaucracy and because of its overcrowdedness and uncleanliness.

Refugees (and the Indian population) depend to a large extent on the influx of tourists, including the transient “dharma bums” and those on more committed spiritual or welfare missions. The new refugees find themselves

outside the rigid structures of Tibetan society, perched at the margins of Indian society, and inferior to all around them owing to their utter dependence.

Chapter 2 explores the notions of “tradition” and the “rich cultural heritage of Tibet”, which “authenticate the past and largely discredit the present”. The chapter opens at a Tibetan wedding, with a group of older chang-ma women singing songs of blessing and offering barley beer in toasts to the couple and the guests.

Groups like this had been common in Tibet before 1959, but only became popular in Dharamsala in the 1980s. The women performing for the wedding had all fled from the Tingri region of Tibet, working in Nepal as day labourers, petty traders, or wool spinners before reaching Dharamsala. They had recently pooled their memories of weddings in old Tibet to create a suitable repertoire.

At some remove from such non-institutional groups, Diehl examines the role of government-sponsored community and school events in “cultural preservation”, headed by the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA).

In exile the official drive was inspired both by the dilution of Tibetan culture after exposure to Indian society and by fears over the destruction of traditional culture inside Tibet after 1959 (this mantra, still repeated by rote, probably needs refining in view of research on the state of performing traditions in Tibet since the 1980s). The reified cause of “preservation” required perpetuating a sense of “loss and victimisation” among the second and third generations, who had no experience of the homeland.

But the nostalgic canonisation of certain genres

does little to account for (or respect) the complex mosaic of cultural practices that are continually being constructed in exile through the choices and circumstances of even the most “traditional” Tibetan refugees and that constitute their day-to-day realities.

Nor does it reflect the diversity of culture inside Tibet before the 1950s, and since the 1980s.

Diehl scrutinises the annual ache-lhamo festival of the TIPA Tibetan opera troupe (see here, a post enriched by wonderful videos), as well as TIPA’s international touring activities. But locals note that the school appears demoralised, its performances lacking vitality—the emphasis on preservation apparently leading to “cultural death”, just as in China.

Diehl notes the uncomfortable position of the sar-jorpa “new arrivals” from Tibet:

Rather than being valued as fresh connections to the increasingly remote homeland, as might be expected, these Tibetans more frequently cause disappointment by failing to validate the hopeful dreams of those living in exile. Instead, their apparent foreignness only confirms dire thirdhand news of cultural change (namely, sinicization) in Tibet.

Still, educated Tibetans in Dharamsala told Diehl that

the children escaping nowadays from Tibet (rather than those carefully schooled in exile) are the most likely to maintain a strong commitment to the “Tibetan Cause”, since they have personally experienced the consequences of living under Chinese occupation.

She illustrates the conflict with a telling scene at the Losar New Year’s gatherings. Besides the chang ma singing songs of praise and dancing, a group of new arrivals from Tibet were also taking turns to sing namthar arias from ache-lhamo opera, with loud amplification—a performance shunned by the locals.

It seemed a perfect illustration of the separate worlds refugee Tibetans and Tibetans raised in the homeland inhabit, even when living and dreaming in the same close physical proximity. No Tibetan in the temple that morning wanted to be celebrating another new year where they were, and all knew exactly where they preferred to be, but the differences between their relationships to those reviled and desired places [were] being expressed in ways that exaggerated the temporal, spatial, and cultural experiences that had been their karmic destiny, seemingly muting their commonality.

Diehl goes on to ponder the competing claims to cultural authority in Tibet and in exile. The singers visiting from Tibet were not making explicit claims to “tradition”, but, rather,

employing the range of their musical knowledge […] to express conservative and religious sentiments. Because they had recently come from the physical homeland, their potential space-based authenticity was actually a liability in the context of Dharamsala rather than a resource for claims to cultural propriety. […]

Young Tibetans in Tibet and in exile are not faced with a simple either-or choice between traditional or modern “styles”. […] It is difficult to assess most traditions as simply “preserved” or “lost”. *

Still, cultural pundits in Dharamsala see the risk of Chinese influence as more pernicious than that of other kinds of foreign music such as rock-and-roll. Exiles have criticised the vocal timbre of Dadon, a Tibetan pop singer who escaped Tibet in 1992, as sounding “too Chinese”; even more strident was the controversy over Sister drum.

Chapter 3, “Taking refuge in (and from) India: film songs, angry mobs, and other exilic pleasures and fears”, discusses refugee life in the here and now of contemporary India, when

few voices in the conversation grapple with, or even acknowledge, the Indian context in which the exile experience is actually taking place for the great majority of Tibetan refugees.

The shared disdain of many Westerners and Tibetan refugees for the day-to-day realities of India—hardship, corruption, poverty, and filth—is an important ingredient in the often-romantic collusion between these groups.

The Indians’ resentment of the refugees is “restrained by considerations of economic self-interest”, but ethnic conflicts sometimes arise, as in April 1994, when a fight between a Tibetan and a local gaddi led to a rampage against the refugees. The Dalai Lama’s offer to move out from Dharamsala was clearly in no-one’s interest, and so peace-making gestures were made.

Living in India, Tibetan refugees are no more immune than the rest of the subcontinent to the ubiquitous Hindi film music, with all its “fantastic dreams of sin and modernity”, in Das Gupta’s words. Commenting on the wider consumption and production of such songs among Tibetan refugees, Diehl reflects in a well-theorised section on the similarities and differences between the original and the mime.

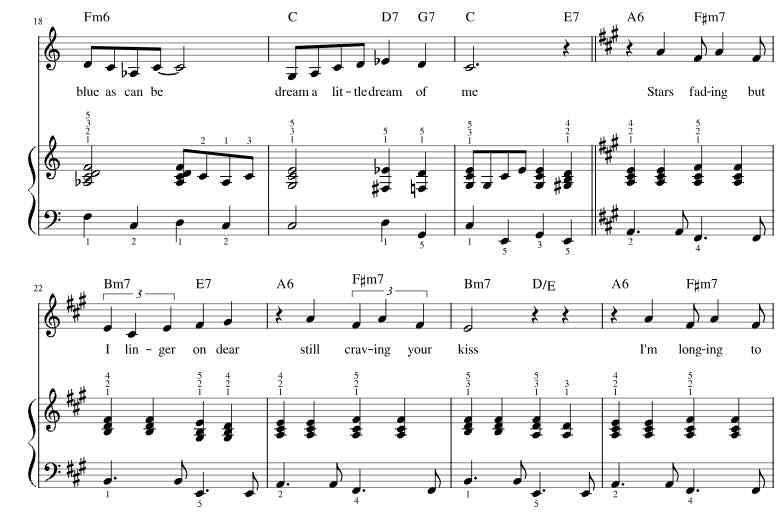

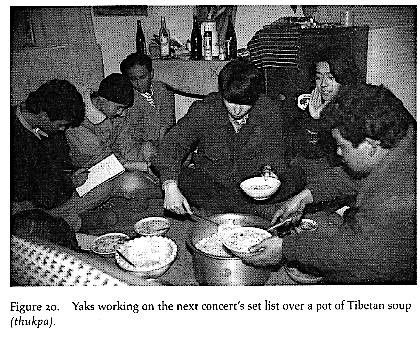

Although Hindi film songs had long been adopted by Tibetan refugees as “spice” (or “salt-and-pepper”) at weddings and other events, they were to make a more conflicted choice for Tibetan rock groups. Diehl takes part in the Yak Band as they perform concerts that include some such songs, featuring the demure young schoolteacher Tenzin Dolma, who imitates the voice of Lata Mangeshkar, “the Nightingale of India”. Tibetans’ enjoyment of this repertoire is a guilty pleasure. The Yak band were aware of the risk that the “salt-and-pepper” might become “bread and butter”.

Having added India into the mix, Diehl reflects further on her time with the Yak Band in Chapter 4, “The West as surrogate Shangri-La: rock and roll and rangzen as style and ideology”, exploring the often-idealised romance with the West, and the quest for independence.

Paul McCartney and Eric Clapton have been part of the lives of Tibetans born in exile since childhood. Western rock brings as much cultural baggage as the soundscapes of traditional Tibet, modern India, and socialist China. Diehl notes the scholarly tendency to interpret youth culture in terms of “resistance” or “deviance”, downplaying cases where it may be conservative or centripetal. Referring to Bishop and Lopez, she surveys the Western fascination with first the “spirituality” of Tibet and then the high profile of the Tibetan political cause.

Social divisions in Dharamsala are further amplified when Tibetans who have gained residency in the USA return for a visit; those still left behind in India, not realising the hardships their fellow Tibetans have had to endure in the States to gain a foothold there, envy their apparently affluent lifestyle. But as refugees continue to arrive from Chinese-occupied Tibet, opportunities for those still in India remain limited; the lure of the West is strong.

Still, plenty of Tibetans of all ages in Dharamsala (including “new arrivals”) felt that Western pop and rock “have no place in a community engaged in an intense battle for cultural survival”.

On the one hand, there are very strong, politically informed reactions against any Tibetan music that sounds too Chinese, too Hindi, or too Western. On the other, many Tibetan youth respect traditional Tibetan music but find it boring.

In Chapter 5, “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down: making modern Tibetan music”, Diehl ponders the challenges of creating a modern Tibetan music. She provides a history of the genre from its origins around 1970, introducing the TIPA-affiliated Ah-Ka-Ma Band before focusing on the Yak Band.

Paljor was brought up in Darjeeling, trained by Irish Christian missionaries. His late father was a Khampa chieftain who had been trained by the CIA in the late 1950s to fight Chinese incursion. Thubten, grandson of a ngagpa shaman, had escaped as a small child from Shigatse to Kalimpong in 1957, going on to spend seventeen years in the Tibetan regiment of the Indian army. Phuntsok was born in Dharamsala; Ngodup was an orphan schooled in Darjeeling.

In a community wary of innovation, even traditional musicians have a lowly status. Whatever people’s private tastes within the family, public musicking is subject to scrutiny.

Chapter 6 turns from sound to the crafting of song lyrics, with their narrowly solemn themes such as solidarity for independence, and nostalgia for the loss of a beautiful homeland—themes which demand expression in a language that is largely beyond the literary skills of the younger generation. Diehl talks with the official astrologer for the government–in-exile, who provided poetic lyrics for the local bands, and introduces the early work of Ngawang Jinpa, Paljor’s teacher in Darjeeling. Diehl cites a rather successful lyric by Jamyang Norbu (former director of TIPA, editor of the 1986 Zlos-gar, an important resource at the time; see e.g. The Lhasa ripper, Women in TIbet, 2, and The mandala of Sherlock Holmes), “poetic yet accessible, evocative rather than boring”.

She gives a theoretically nuanced account of what song lyrics communicate, and how; and she explains the refugees’ rather low level of literacy, official efforts to create a standard language among a variety of regional dialects, and the link with sacred sound. Love songs are also composed, but hardly performed in public. It is considered more acceptable to write lyrics in bad English than in bad Tibetan, but such songs are rarely aired in public.

Chapter 7 unpacks public concerts that “rupture and bond”. In January 1995, the Yak Band made a major trek to the Mundgod refugee settlement in south India to coincide with the Kalachakra initiation ceremony there, with the Dalai Lama presiding. Their choice of repertoire over fifteen nightly performances revealed “a comfort with cultural ambiguity and a passion for foreign culture that is disturbing to some in the community”.

Over the course of the concerts the band agonised over their set list. While their inspiration was to share their songs of praise for the Dalai Lama, their longing for a homeland they had never seen, and compassion for their compatriots left behind in Tibet (exemplified in their opening song Rangzen), they varied the proportion of modern Tibetan songs, “English” rock songs, and Hindi and Nepali songs in response (and sometimes resistance) to the reactions of the multi-generational audiences—which included, at first, young monks, before their abbot imposed a strict curfew on them. While hurt that the audiences preferred “silly Indian love songs” to their core Tibetan offerings, the Yaks reluctantly succumbed to popular demand.

One of the Yaks’ reasons for their visit to Mundgod was to get their tenuous finances on their feet by selling their cassettes, but they returned to Dharamsala having made a loss. Moreover, they now suffered from hostile public opinion about their repertoire.

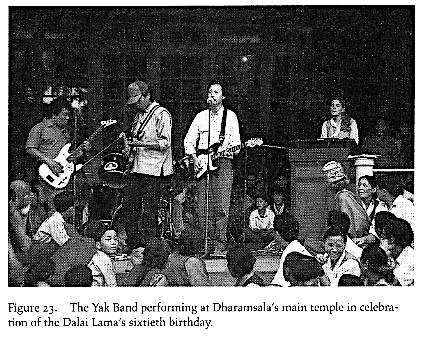

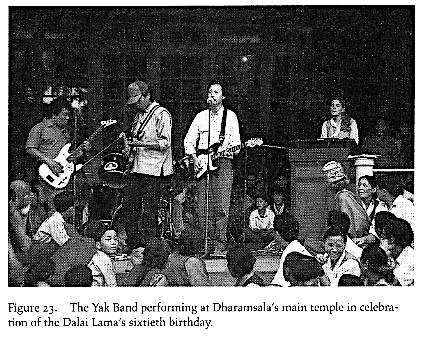

Disillusioned by the lack of support in Dharamsala, the band drifted apart, but they were able to put on a reunion gig for the Dalai Lama’s 60th birthday—when their preferred Tibetan set list was eminently suitable.

Disillusioned by the lack of support in Dharamsala, the band drifted apart, but they were able to put on a reunion gig for the Dalai Lama’s 60th birthday—when their preferred Tibetan set list was eminently suitable.

In the Conclusion, Diehl reminds us of the importance of musicking

as a crucial site where official and personal, old and new, representations of Tibetan culture meet and where different notions of “Tibetan-ness” are being confronted and imagined.

In a brief coda she updates the stories of the Yak Band.

* * *

For all the book’s excellent ethnographic vignettes, some sections bear the hallmarks of a PhD, with little adaptation to a more reader-friendly style—which is a shame, since the topic is so fascinating. I’ve already confessed my low tolerance threshold for heavily theorised writing (see e.g. my attempts to grapple with Catherine Bell’s outstanding work on ritual).

From within the goldfish bowl of Dharamsala, Diehl only touches in passing on the changing picture inside Chinese-occupied Tibet. While repression there has been ever more severe since 2008, research on regional cultures there had already become a major theme, with a particular focus on Amdo (see e.g. here, including the work of Charlene Makley, Gerald Roche, and others, as well as chapters in Conflicting memories). For the pop scene, useful sources are §10 of the important bibliography by Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy (including work by Anna Morcom), and the High Peaks Pure Earth website (see also Sister drum, and Women in TIbetan expressive culture). Within occupied Tibet, performers of popular protest songs have been imprisoned, such as Tashi Dhondup; in another thoughtful article, Woeser explores the shifting sands of prohibited “reactionary songs” and the challenge of keeping track of subtle allusions.

Diehl refers to a variety of publications such as those of Marcia Calkowski and Frank Korom, and I cite some more recent sources in n.1 here—among which perhaps the most useful introduction to the topic is

- Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy, “Easier in exile? Comparative observations on doing research among Tibetans in Lhasa and Dharamsala”, in Sarah Turner (ed.), Red stars and gold stamps: fieldwork dilemmas in upland socialist Asia (2013).

For contrasting lessons from occupation and exile, see also Eat the Buddha. Despite the presence of the Dalai Lama, Dharamsala has begun to occupy a less iconic position in our images of Tibetan culture. For all the growing disillusion with the political promises of Western countries, refugees continue to move on, while “new arrivals” have come to make up a significant component of the town’s Tibetan population—see e.g. Pauline MacDonald, Dharamsala days, Dharamsala nights: the unexpected world of the refugees from Tibet (2013), critically reviewed here. The growing popularity of satellite TV from the PRC, and the issue of Tibetan culture in the growing Western diaspora, further complicate the story.

Ethnographies, however definitive they may seem at the time, are always overtaken by more recent change. While soundscape is always an instructive lens on society, more general studies of Dharamsala lead us to a wealth of research on Tibetan refugees in south Asia by scholars such as Jessica Falcone, Trine Brox, Rebecca Frilund, and Shelly Boihl.

See also Lhasa: streets with memories, and The Cup. For the perils of “heritage”, see this roundup, and for a broad discussion of “authenticity”, note Playing with history.

* One of my own more disconcerting moments came while hanging out with young performers from TIPA on their tour of England in May 2004. Several of them were refugees from Chinese-occupied Tibet, but they were quite happy to speak Chinese with me. Much as I am attracted to Tibetan culture, apart from lacking the language skills, my whole background in Chinese culture has always made me wary of doing fieldwork in Tibetan areas. Whenever I meet Tibetans I am at pains to point out that my Chinese peasant mentors have also suffered grievously at the hands of the state, but I’m still anxious that they might consider me tarred with the brush of the invaders. Still, incongruously, several of the TIPA performers who had fled the PRC were now keen that I should sing them some Chinese pop songs to remind them of their old home, and were somewhat disappointed when I couldn’t oblige.

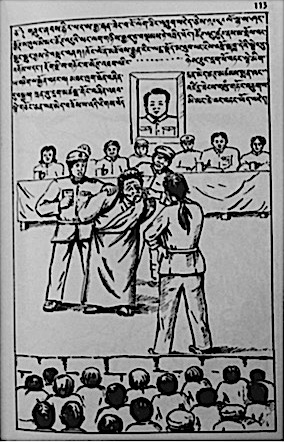

This detail is particularly fine:

This detail is particularly fine:

For more recent Uncle Xi pinups, and incentives to display them, see

For more recent Uncle Xi pinups, and incentives to display them, see

Orgyen displays his “shrine”.

Orgyen displays his “shrine”.

The night we visited, the club—founded by Zuhal Focan (left) with her husband Önder—was hosting the Swiss drummer Cyril Regamey, with François Lindeman (piano) and Andreas Metzler (bass), who came together with local jazzmen Bora Çeliker (guitar) and Can Ömer Uygan (trumpet) to pay homage to the amazing creativity of

The night we visited, the club—founded by Zuhal Focan (left) with her husband Önder—was hosting the Swiss drummer Cyril Regamey, with François Lindeman (piano) and Andreas Metzler (bass), who came together with local jazzmen Bora Çeliker (guitar) and Can Ömer Uygan (trumpet) to pay homage to the amazing creativity of

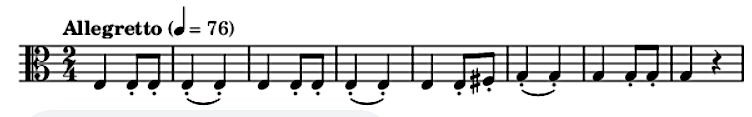

Chandrima Misra directing students, Founders’ Day, March 2022.

Chandrima Misra directing students, Founders’ Day, March 2022.

From Blue kite (Tian Zhuangzhuang, 1993).

From Blue kite (Tian Zhuangzhuang, 1993).

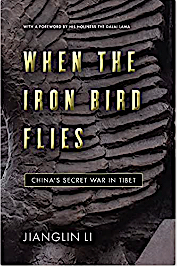

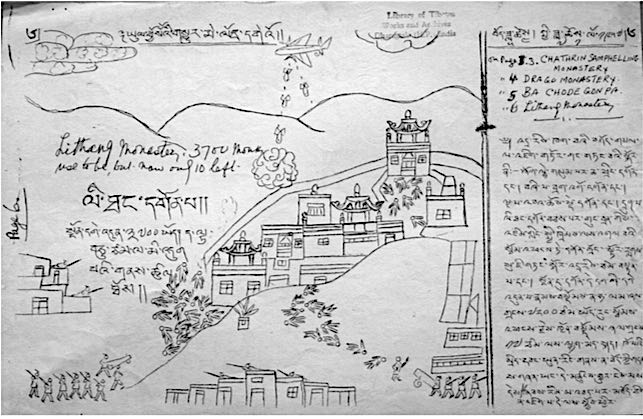

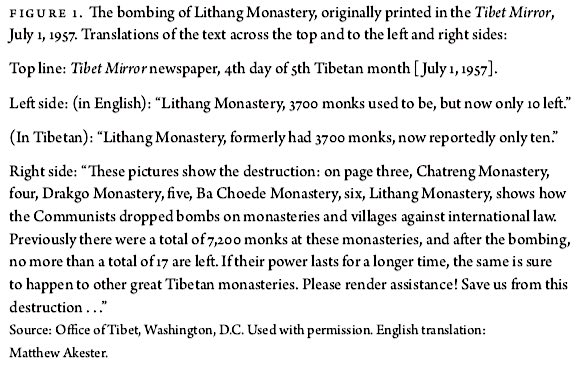

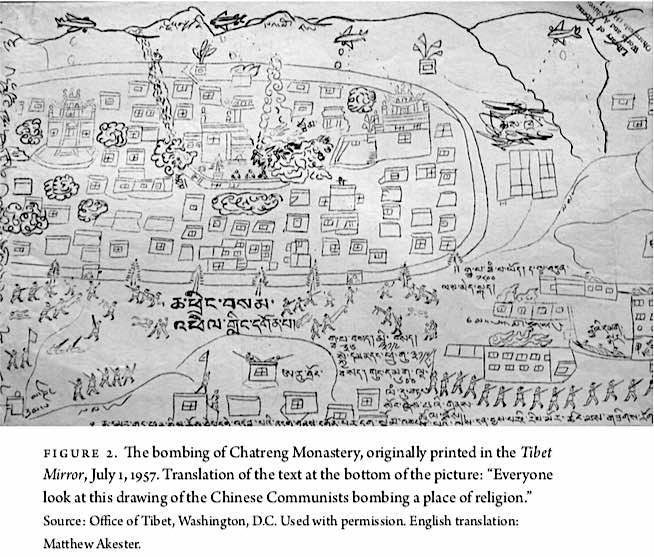

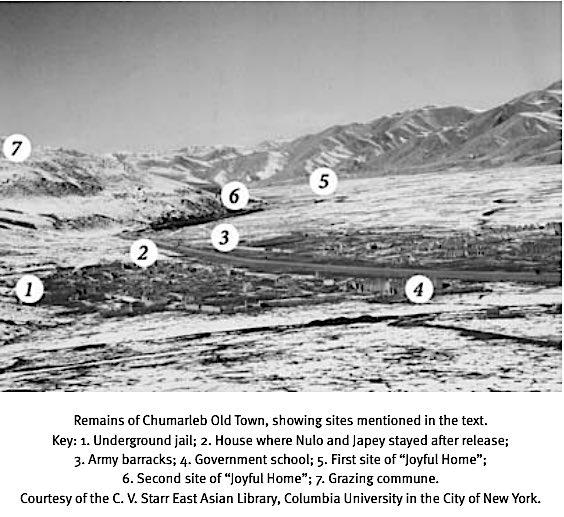

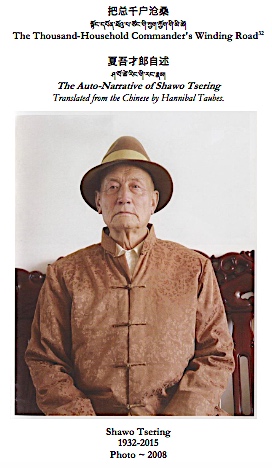

Another account of the catastrophe that befell the Tibetan region of

Another account of the catastrophe that befell the Tibetan region of

Large queues formed for the National Gallery concerts.

Large queues formed for the National Gallery concerts.

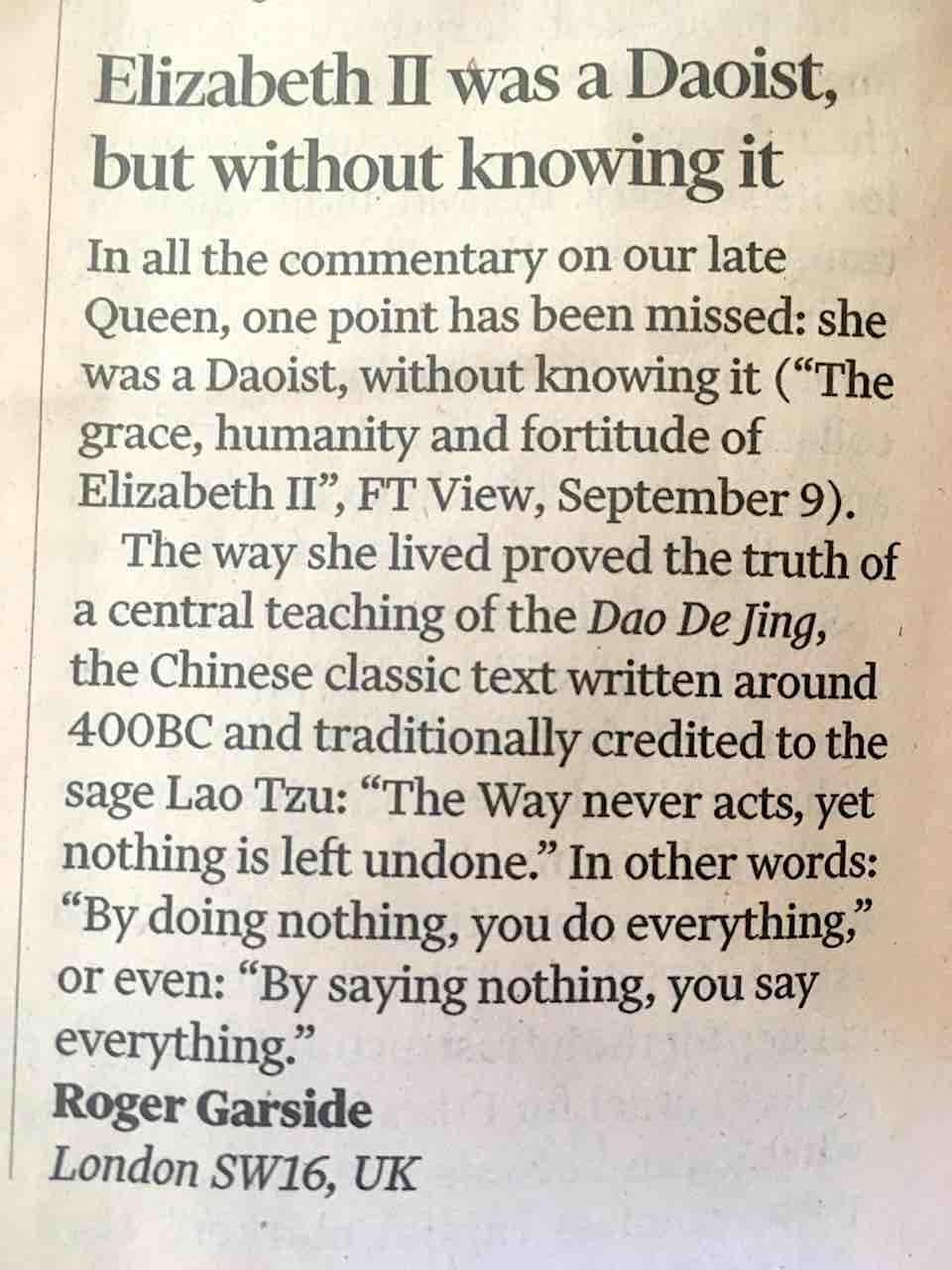

Sadly, we perhaps need to list some other pastimes that don’t necessarily qualify for the status of “Daoist”:

Sadly, we perhaps need to list some other pastimes that don’t necessarily qualify for the status of “Daoist”:

Shortly before

Shortly before

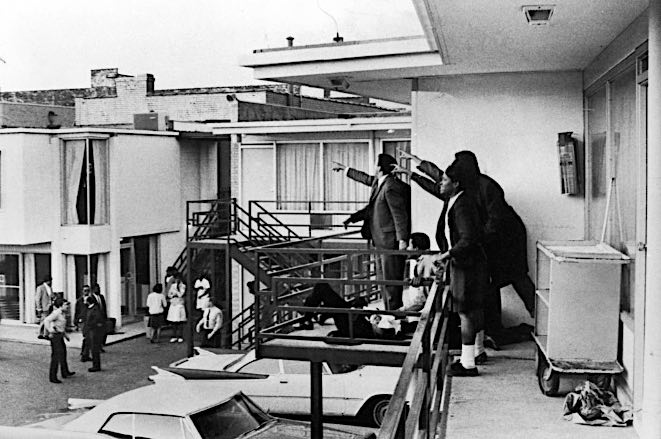

Dr King’s supporters point in the direction of the shooting.

Dr King’s supporters point in the direction of the shooting.

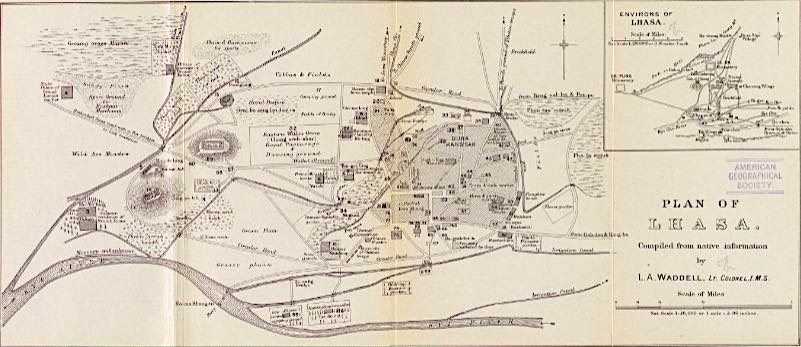

Plan of Lhasa, 1904, by L.A. Waddell.

Plan of Lhasa, 1904, by L.A. Waddell.

Disillusioned by the lack of support in Dharamsala, the band drifted apart, but they were able to put on a reunion gig for the Dalai Lama’s 60th birthday—when their preferred Tibetan set list was eminently suitable.

Disillusioned by the lack of support in Dharamsala, the band drifted apart, but they were able to put on a reunion gig for the Dalai Lama’s 60th birthday—when their preferred Tibetan set list was eminently suitable.

Le mépris (Contempt, 1963), with Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli, is so overladen by Godard’s already signature style that it hardly seeks to do justice to the “humiliation and sexual frustration” of

Le mépris (Contempt, 1963), with Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli, is so overladen by Godard’s already signature style that it hardly seeks to do justice to the “humiliation and sexual frustration” of