Further to Dream songs, I’ve been admiring

- Amanda Harris, Representing Australian Aboriginal music and dance 1930–1970 (2020).

The perspective of non-Indigenous art-music composers writing for the public stage may seem niche:

From a music history or musicology perspective the music and dance events that feature would commonly be perceived as peripheral to the main story. They are not the events that have contributed to the canon of important moments in Australia’s music history, itself a minor player in the canon of (European) Western art music. In the histories of Western art music taught in Australia’s conservatoria and high school music courses, the events which feature here are not even a blip on the radar of music history.

Thus Aboriginal culture itself has been marginalised, as has Australian composition within the wider sphere of WAM; and within the latter, Aboriginal-inspired works may seem even more peripheral. However, Harris puts in focus many important issues underlying the encounter between the broad categories of “folk” and “art” musics, making a fascinating story.

The period from 1930 to 1970 was characterized by government assimilationist policies aimed at “protection” and “welfare”. The book is focused primarily on the southeast and the ways that representation of Aboriginal music and dance linked urban centres to Australia’s Top End and its Red Centre.

Many of the works described here tap into “an appetite for representations of Aboriginality devoid of Aboriginal people”:

Non-Indigenous Australians have engaged more readily with works that could be disembodied from the people who created them, than they have with living, singing, moving Aboriginal people. […]

As Linda Tuhiwai Smith reminds us, Indigenous peoples have long been appalled by the way “the West can desire, extract, and claim ownership of our ways of knowing, our imagery, the things we create and produce, and then simultaneously reject the people who created and developed those ideas and seek to deny them further opportunities to be creators of their own culture and own nations”.

Importantly, Harris listens to the accounts of Aboriginal people themselves, “disrupting” the chapters with three essays. While these commentators partly share the values of the settler majority, they are attuned to the ways of their forebears.

Australian Aboriginal people’s rich oeuvres of song and dance point to the importance of embodied and auditory modes of knowledge transmission and continuance in the same way that the West’s libraries of books and reams of paper archives reveal the dominance of the visual and the written in European epistemologies. […]

Under protection/assimilation regimes, immense pressure was exerted upon Aboriginal people to abandon culture by banning the speaking of Indigenous languages and performance of ceremony and by rewarding actions that showed Aboriginal people were adopting mainstream behaviours like residing in a single house, in a nuclear family unit. These pressures were not just notional, but rather, punitively enforced—people who grew up under this regime remember mothers, aunts and grandmothers obsessively dusting and keeping a clean house, knowing that untidiness could lead to allegations of neglect of children, and that children were routinely removed from their families and placed in institutional care, sometimes indefinitely.

Nevertheless, at moments of national nostalgia, events commemorating European settlements sought to memorialise and celebrate the lost arts that had been actively repressed.

Such events go back to the start of the century, becoming more common from the 1930s. Aboriginal people were presented to gawping non-Indigenous audiences as “noble savages”.

Chapter 1 a general introduction, opens with the 1951 Jubilee of Federation, featuring the Corroboree, a symphonic ballet composed in 1944 by John Antill with new choreography by Rex Reid.

Instead of the dozens of Aboriginal people proposed by the publicity subcommittee, Corroboree presented dozens of orchestral musicians from the symphony orchestras of each state and dancers from the National Theater Ballet Company. No Aboriginal people were involved in the production. The show was acclaimed as a landmark Australian work. […]

Non-Indigenous Australians have appropriated this language to stake a claim in Aboriginal culture and to represent Aboriginal music and dance to non-Indigenous audiences. […] But what relationship do these songs bear to those that Aboriginal people were singing?

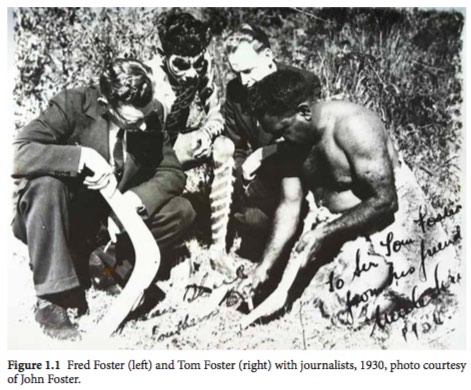

In the Prelude that follows, D’harawal scholar Shannon Foster recalls her great-grandfather, the activist and songman Tom Foster, who spoke out on Aboriginal rights at the Day of Mourning in Sydney in 1938.

As she observes tellingly,

The archival research space is full of contradictions for Aboriginal people. I cannot help but feel a forging of my cultural identity when the archives unveil another piece of “evidence” of who we are and who I come from. I do not need Western research to validate who I am, though it still performs this task, whether I want it to or not. I can use the archives to tell the stories of the destruction of colonization and the violence that has been inflicted on my family, and I need people to know that it is there and not deny it. But I do not want others to misuse this information and to paint us as victims or use our damage to sell their research: to perversely and voyeuristically indulge in our pain and damage. […]

Every time I relish another crumb of information about my grandfathers, the joy is tinged with despair at not knowing or seeing this information until it is delivered to me through a white man’s colonial archive, stained with the blood and pain of our ancestors.

And

I am told by a prominent historian in the audience that they had always seen boomerangs like Tom’s as nothing more than kitsch, cultural denigration, humiliation, and damage. They had never considered (nor thought to ask) how we feel about them. It had never occurred to them that what we see is physical evidence of our existence in a world where we have been consistently erased. Tom’s boomerangs speak to us of survival, resistance, and cultural fortitude and strength.

This account makes a bridge to Chapter 2, on the 1930s. Though Tom Foster took part in the troubling silent film In the days of Captain Cook (1930), he was among those asserting the enduring presence of Aboriginal people in society.

As various official commemorations were staged through the 1930s, Harris describes the Aboriginal presence at the opening of the Sydney Harbor Bridge in 1932. The 1938 reenacting of the First Fleet landing was attended by historical pageants—and the Day of Mourning protests. By contrast with the quotidian limitations on their mobility, the performers were coerced into travelling to Sydney.

Anthropologists had long been recruited to government agencies. They now acted as cultural brokers between performers, the arts sector, and the media; under A.P. Elkin a shift occurred from protection to assimilation.

A major actor in cultural agendas and the new “Australian creative school” was the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC), founded in 1932. Alongside visits by Percy Grainger, composers building on European explorations in harnessing folk styles included Clive Douglas, John Antill, and Margaret Sutherland.

Chapter 3, “1940s: reclaiming an Indigenous identity”, surveys wartime performances for recruitment rallies; and after the war, the forming of groups like the radical New Theatre, whose productions included the 1946 Coming our way and the ballet White justice, with Eric and Bill Onus coming to the fore.

Ted Shawn, co-founder of the modern American dance movement, was deeply impressed by the performance culture he witnessed on a visit to an Aboriginal community in Delissaville (now Belyuen) in 1947. Still, when dancers were recalled for his trip, “many Darwin housewives found themselves without domestic labour”.

I note that in 1950s’ China too, under the avuncular eye of the Party, dance made a forum for modern experiments, as in the Heavenly Horses troupe in Shanghai (see Ritual life around Suzhou, under “Mao Zhongqing”).

Harris refers to the short 1949 documentary Darwin: doorway to Australia (filmed in 1946), which includes footage of a tourist corroboree in Darwin Botanic Gardens (from 6.23):

As Aboriginal activists continued to meet obstacles, the Aboriginal tenor Harold Blair was exceptional with his recital tours of the USA. Meanwhile the ABC was promoting non-Indigenous composers in “representing an Aboriginal idyll”.

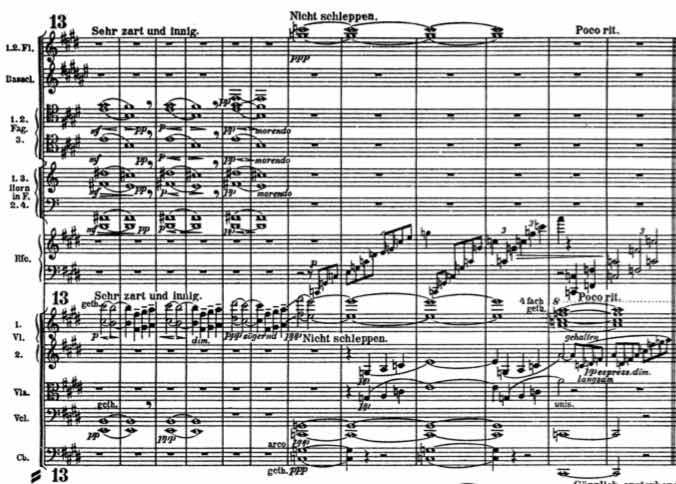

Within this niche, John Antill and his Corroboree, with its clapstick beat persisting amidst the “modernist antics” of the orchestra, made a considerable impact, suggesting comparisons with The Rite of Spring:

New organisations supplementing the cultural work of the ABC included the Arts Council of Australia. Echoing Chinese clichés, “international cultural exchange” now “took Aboriginal music to the world”—specifically to the USA, as Australia’s ties with its imperial parent were downgraded. Ironically,

Just as Aboriginal people were increasingly steered away from maintaining their own cultural practice, non-Indigenous people turned new attention towards it.

But Aboriginal performers still met with obstacles in touring abroad.

Chapter 4 sets forth from the debates surrounding the 1951 Jubilee celebrations. The official cultural initiatives of these years were accompanied by strikes and protests. Performances took on a political dimension, with Bill Onus and Doug Nicholls taking leading roles in asserting Aboriginal rights.

As others have noted, Aboriginal visual and material arts are more readily packaged, reified, than their expressive culture. Despite their sincere aim of enhancing Aboriginal status, the Jubilee committee’s proposals for massed corroborees didn’t come to fruition, being replaced by Antill’s Corroboree. Still better received was the new dance drama Out of the dark: an Aboriginal moomba.

Linking Corroboree to the political, economic, and social exclusion suffered by the Aboriginal owners of the cultures that had inspired it, Margaret Walker of the New Theatre movement proposed her own alternative. She saw Aboriginal people as both a society of “primitive communism” and an oppressed group to be liberated through socialism. In 1951 the Unity Dance Group even toured to East Berlin. In 1958 Aboriginal soprano Nancy Ellis toured China, just as convulsive political campaigns were intensifying there.

Among arts bodies in the 1950s, the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust was founded in 1954—looking forward to a cultural renaissance of a type later ridiculously promised by Brexiteers. The Adult Education Boards sponsored major tours by Beth Dean and Victor Carell, whose ethnographic shows introducing song and dance from around the world gave a role to Aboriginal culture—albeit based, until their 1953 “expedition”, on reading anthropology rather than any acquaintance with the people themselves. In 1954 Dean did a new choreography of Corroboree. For events to mark newly-crowned Queen Elizabeth’s 1954 visit, Aboriginal performers again had to travel large distances to perform.

Debra Bennet McLean brings us down to earth:

We asked ourselves how many Aboriginal people could ever really contemplate, let alone afford, to attend the ballet in the era of the “colour bar”; most Aborigines could not walk freely into an Australian town without an exemption form or “dog tag” at the time of Antill’s composing Corroboree, nor could they even sit in the same milk bar or use public toilets at the time of the premiere of the ballet Corroboree.

Harris writes with such empathy about all the diverse actors in these encounters that the following Interlude is timely, refocusing on the people who were the object of all this well-meaning attention, with Tiriki Onus thoughtfully reflecting on his grandfather Bill (for whose films, see here).

In Chapter 5: 1960 to 1967, Aboriginal performers begin to take the main stage. Harris discusses opportunities for public performance and the limitations imposed by state agencies. She begins with talent quests from 1961, the North Australian Eisteddfod, and tours of northern companies in the south—notably the well-received Aboriginal theatre, presented in Sydney by Aboriginal people from north Australia in 1963. Such shows

aimed simultaneously to engage those interested in Aboriginal performance from an ethnographic and/or historical perspective and those creating and producing new works of modern dance, music, and visual art on Australian stages.

As Harris notes, a defining feature of these new contexts was the way that performers from different traditions were brought together into a scratch ensemble, or into competition with one another.

In an interview Harris draws attention to a film about the 1964 North Australian Eisteddfod:

Yet international tours remained elusive. In Australia (as in New Zealand and Canada), with Indigenous and European genres competing for resources, the authorities of settler colonies still preferred to highlight their European heritage—by contrast with countries from which British colonisers had withdrawn (Pakistan, India, Kenya, Ghana).

Expatriate Australian Dudley Glass addressed the Royal Society of Arts in 1963,

writing that though Aboriginal people had given little to music [sic!] with their monotonous music and crude instruments [sic!], the “ingenious” John Antill has given a ballet suite “the flavour of aborigine music”, portraying native dance ceremony and using different totems for different parts of the ballet.

This contradictory sentiment, in which Aboriginal music was deemed to have little value and yet non-Indigenous composers were praised as innovative for evoking it in their music, permeated decisions about how Australia should be represented overseas. […]

In representing itself to international audiences, the Australian government sought to maintain a narrative of Aboriginal people as something old and static, not modern and constantly transforming. Tangible art works were sent overseas—works standing in for the artists who had created them, but live performers were excluded from events like the Commonwealth Festival in favour of non-Indigenous composers and performers who would represent Australia as a culture in dialogue with European modernity.

Here, as often, I hear echoes of the Chinese authorities towards their folk culture.

All this leads back to an update on Antill and Dean, with their 1963 Burragorang dreamtime, using non-Indigenous performers. Harris notes the bitter irony that the people whose displacement by the settler colonists was romanticised in the ballets, and embodied by the performers, had themselves just been displaced by a dam project to supply the Sydney population.

Interestingly, Beth Dean reported on Antill attending Aboriginal theatre:

This was far different from anything Antill had seen before. It was not the rather impromptu “tourist version” by Aborigines who had not been living a tribal life for many years, sometimes generations, as they survived on the outskirts of towns. John was thrilled. One may wonder what Antill might have done if he had experienced this kind of Aboriginal music in his early days, rather than on his 60th birthday.

Chapter 6 dicusses the end of the assimilation era—from the 1967 constitutional referendum, which led quickly and decisively to a shift to Aborigines representing their own culture, to the 1970 Cook Bicentenary, marked by protests.

The referendum belatedly paved the way for full rights of Aborigines as citizens. In the performing arts, they now gained greater rights of self-determination, as groups such as the Aboriginal Theatre Foundation and Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre were formed. Although I imagine that such developments had a tangential impact for poor dwellers of the remote Country,

Groups like the Aboriginal Theatre Foundation would be momentous in localising the performance of Aboriginal culture internationally, bringing a regional focus to owned and self-represented cultural practice, in dialogue with global contexts for performance.

In Australia’s music (1967), largely a study of contemporary art music, Roger Covell allowed some space for Aboriginal traditions—recalling the prophetic remarks of Percy Grainger in the 1930s:

What would we think of a Professor of Literature who knew nothing of Homer, the Icelandic sagas, the Japanese Heiki Monogatori [sic], Chaucer, Dante and Edgar Lee Masters? We would think him a joke. Yet we see nothing strange in a Professor of Music who knows nothing of primitive music and folk-music, and music of mediaeval Europe, and the great art-musics of Asia, and who knows next to nothing of contemporary music.

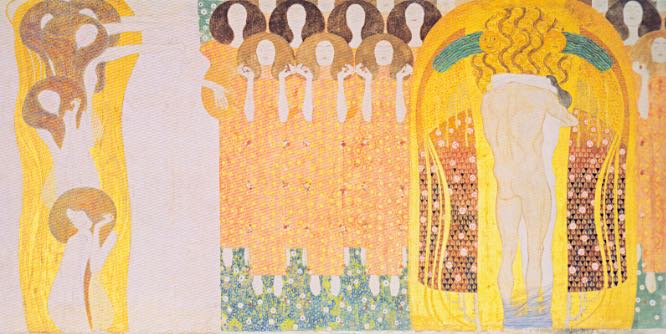

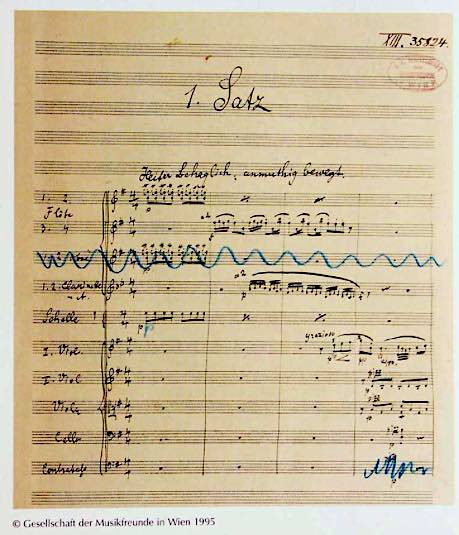

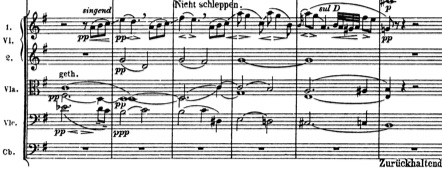

One fruit of this new mindset was the impressive 1971 Sextet for didjeridu and wind instruments, in which composer George Dreyfus collaborated with Aboriginal cultural leader George Winunguj (see cover image above):

For the Mexico Cultural Olympics in 1968, Beth Dean presented the new ballet Kukaitcha, using taped recordings from Arnhem Land, still propagating non-Indigenous representation of Aboriginal culture abroad. Harris comments:

Performing the role of the woman who had transgressed cultural law by witnessing ceremonies forbidden to her in Kukaitcha, while publicly proclaiming her ability to dance men’s dances that women should not even see, Dean seemed more enamoured of the sensationalism of these transgressive actions than of the richness and complexity of the cultures she aimed to represent.

However, new international opportunities for Aboriginal performers were arising, such as performances of the Aboriginal theatre for the 1970 Expo in Japan, amidst complex negotiations.

The 1770 Cook landings, and modern protests over commemoration, are much-studied topics.

Despite the involvement of Indigenous performers, Dean and Carell’s 1970 show Ballet of the South Pacific was now at variance with the prevailing mood. Corroboree was still dusted off, to ever lesser impact.

The re-enactment for the Cook bicentenary, attended by the Queen, with Aboriginal performers among the cast, were now controversial. Protests were a feature of nationwide events.

After the “Too many John Antills?” of Chapter 1, Chapter 7 considers the legacy, progressing elegantly to “Too many Peter Sculthorpes?” and pondering the failure of Australian art music to engage with Indigenous cultures, always (inevitably?) remaining at a remove from Aboriginal performances.

Harris offers a balanced assessment of the inescapable Corroboree:

Antill did not appropriate Aboriginal musical culture. He successfully represented it in a way that settler Australians continued to experience it—as a background presence, a remembered soundscape from childhood, one that was not well understood, was constant, but which would always be subject to inundation by the productivity of nation building. In evoking Aboriginal soundscapes, Corroboree may have appeared to celebrate Aboriginal culture, but the action it performed did the opposite, replacing Aboriginal performance cultures on public stages.

Considering her topic in the light of settler colonial (and post-colonial) theory, she notes that composers’ representations of Indigenous culture “aimed to tame Aboriginal Country and define its value in economic terms”.

Antill’s position as composer of a work that would found a national creative school was not just produced out of his own creative industry and good fortune, rather, it capitalised on the state agenda for representing Aboriginal culture without the messiness of engaging with Aboriginal people and their political demands and physical needs.

As Anne Thomas noted in 1987,

Public dances and performances of folk musics that had been so active in the assimilation era fell away once Aboriginal people were able to advocate for their rights in explicit ways.

Harris goes on to describe later collaborative projects that seem to resist narratives of replacement.

Yet as ethnomusicologist Catherine Ellis observed,

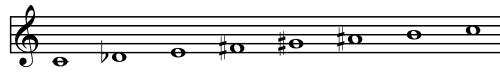

very few composers have taken the trouble to examine the structural intricacies of Aboriginal music. They have preferred to look at the superficialities: a descending melody, a regularly repeated stick beat, a didjeridu-like sound.”

Thus

Though the public rhetoric around these works claimed that they aimed to persuade listeners of the value of Aboriginal culture, value (through public recognition, commissions for new works, performances, and recordings) was attributed to the composers and their works rather than to the cultures that ostensibly inspired them.

Peter Sculthorpe (1929–2014) went on to become the leading figure on the WAM scene in Australia. Inspired at first by Japanese Noh drama, by the 1960s his music showed greater Australian Aboriginal influence. But as Harris comments, his works have such a unique voice that “they no longer resemble the Aboriginal music on which their performative capital is dependent.”

She also surveys recent works by composers such as didjeridu player William Barton.

Harris never loses sight of the perspective of Aboriginal people, or their maintenance of traditional ritual life under trying conditions. In a lively Coda, Aboriginal storyteller Nardi Simpson reflects further on the encounter. She makes a simple, pithy statement:

I want to do something that hasn’t been done before with the tools and knowledge that I have and who I am and where I’m from and that’s what I want to do.

* * *

This is a most thoughtful, compelling study. For a survey of the timeline, see also Harris’s Storymap site.

For the period since, one might also turn to Indigenous pop and rock music, another hybrid forum for creative representation with a more far-reaching influence, less constrained by officialdom. Meanwhile, anthropologists and ethnomusicologists have been ever more active in documenting the enduring ritual life of Aboriginal communities—and protests over Invasion Day continue.

See also Grassy Narrows, Native American cultures, First Nations: trauma and soundscape, and An Indigenous peoples’ history of the United States. For a remarkable vision, cf. Alan Marett’s 1985 Noh drama Eliza. And note What is serious music?!

“What shall we do with all these balls?”

“What shall we do with all these balls?”

The Scherzo is a Totentanz, inspired by Arnold Böcklin’s 1872

The Scherzo is a Totentanz, inspired by Arnold Böcklin’s 1872

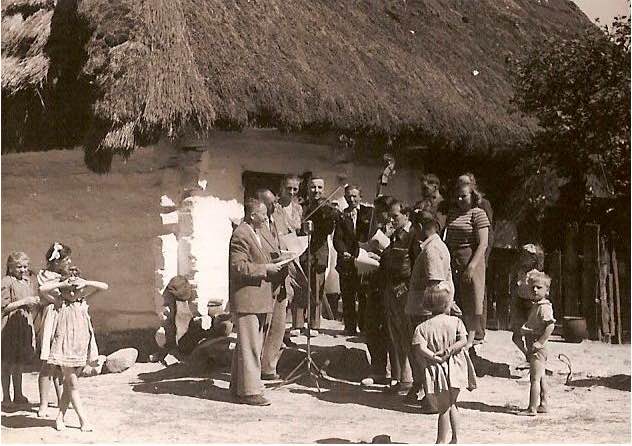

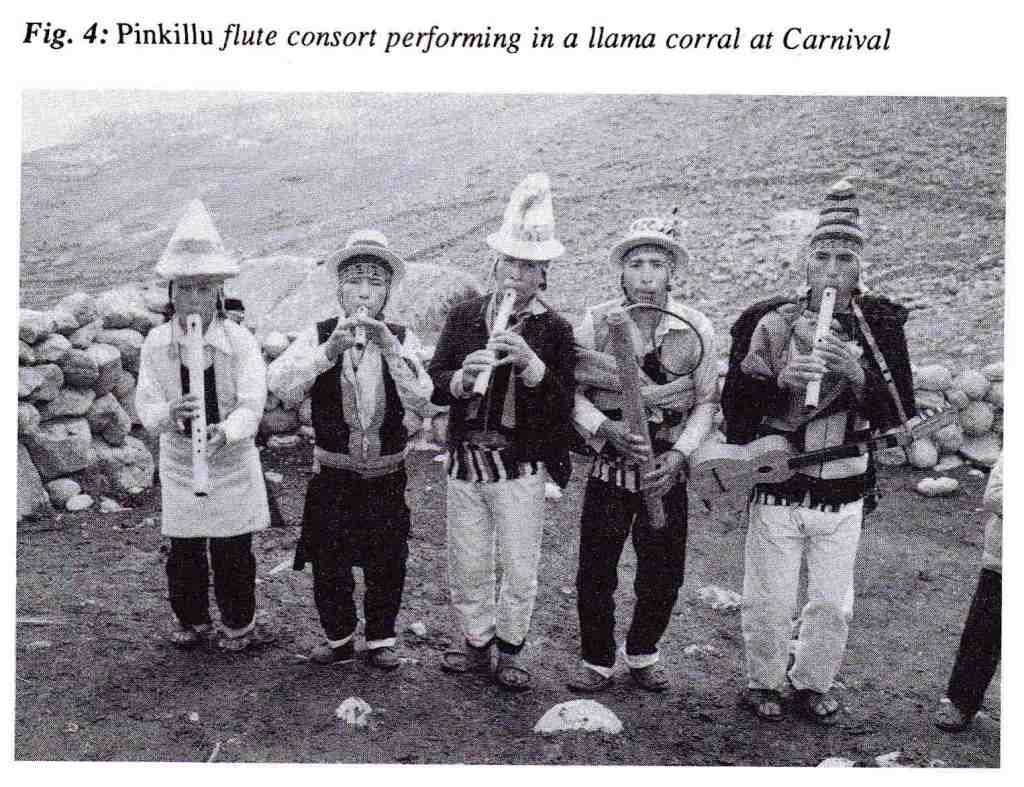

Fieldwork project, early 1950s. Source

Fieldwork project, early 1950s. Source

Anna Mahler. Source

Anna Mahler. Source

Soon I would even learn to tie my own shoe-laces—which stood me in good stead for joining the

Soon I would even learn to tie my own shoe-laces—which stood me in good stead for joining the

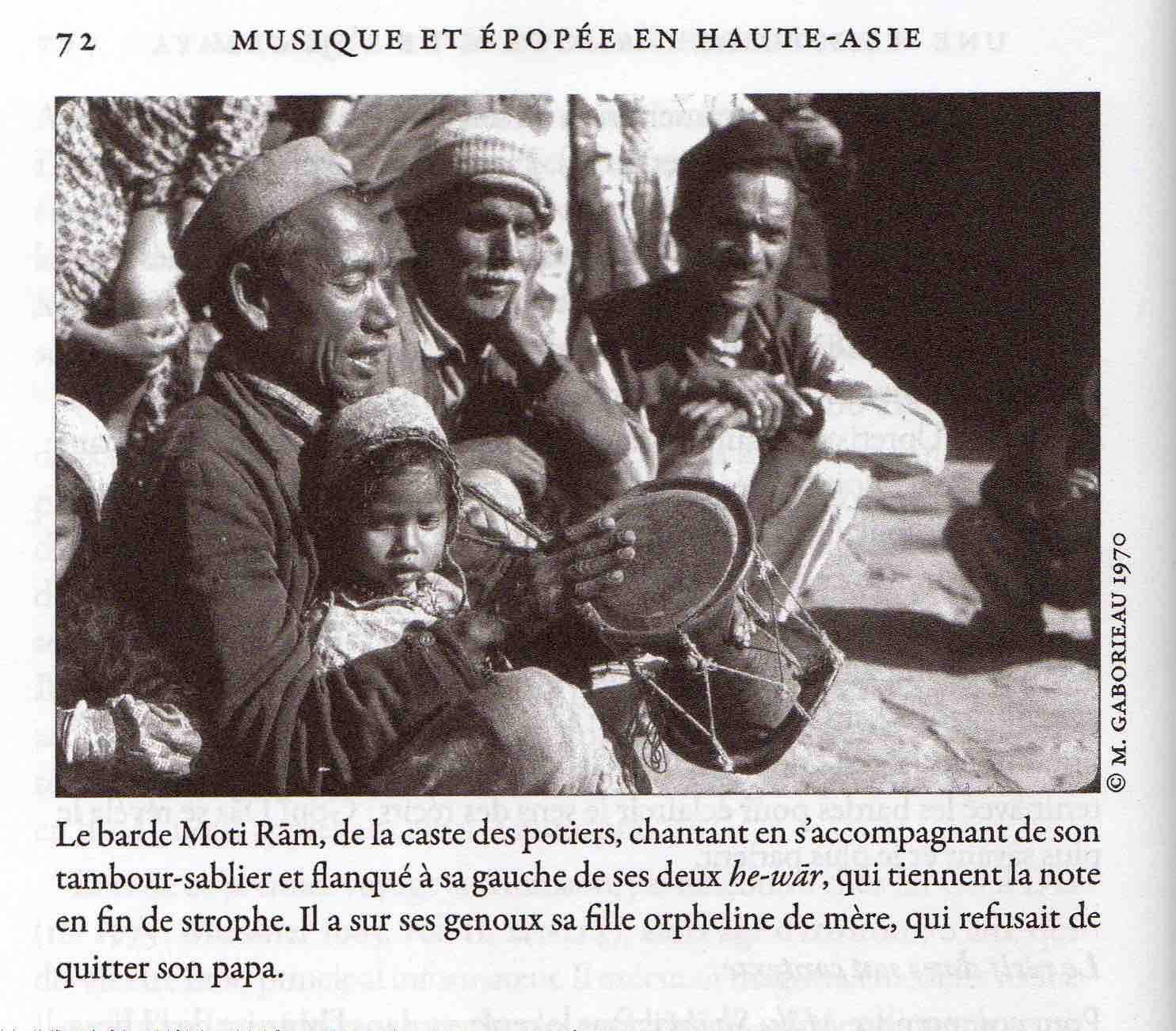

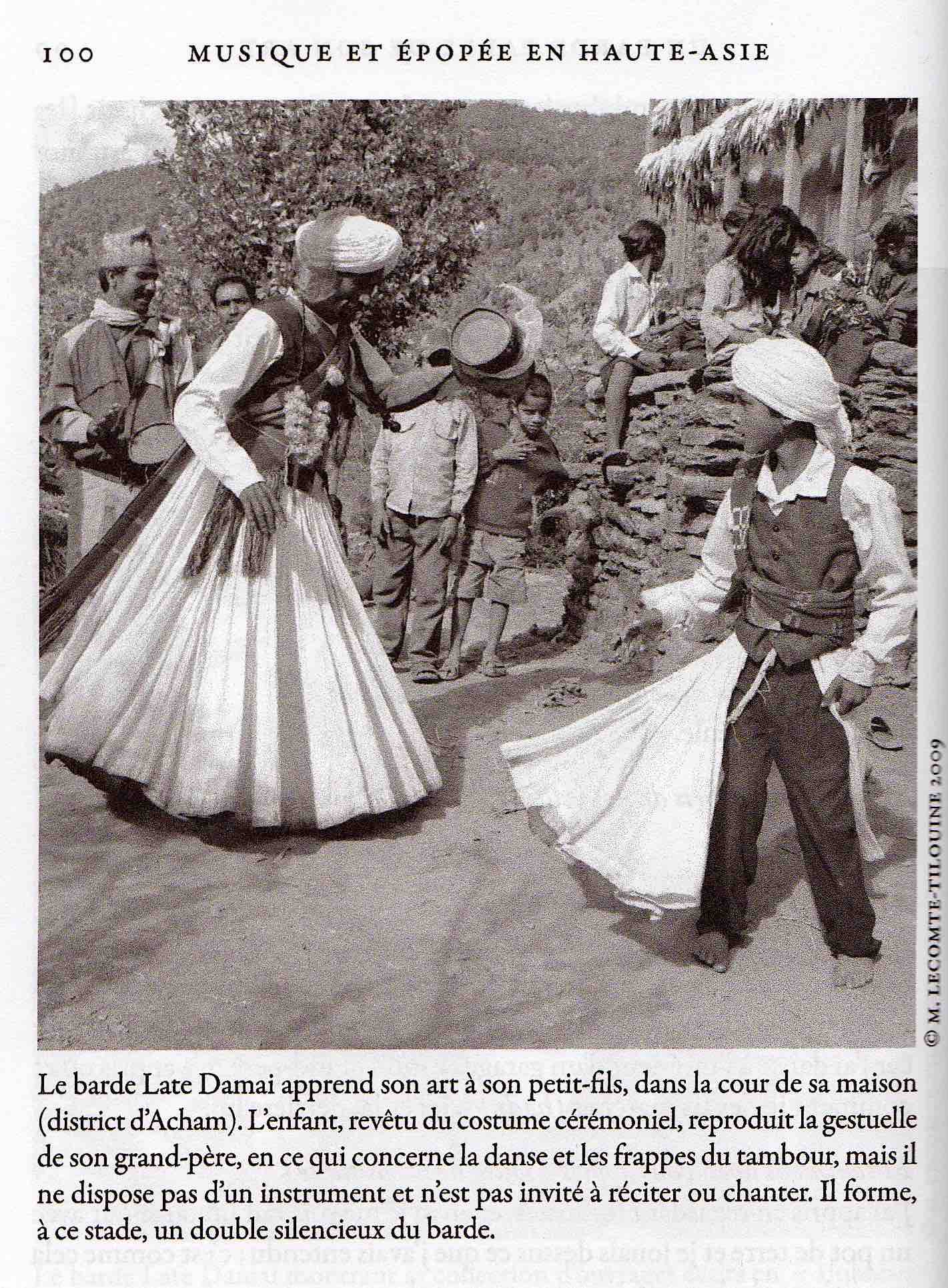

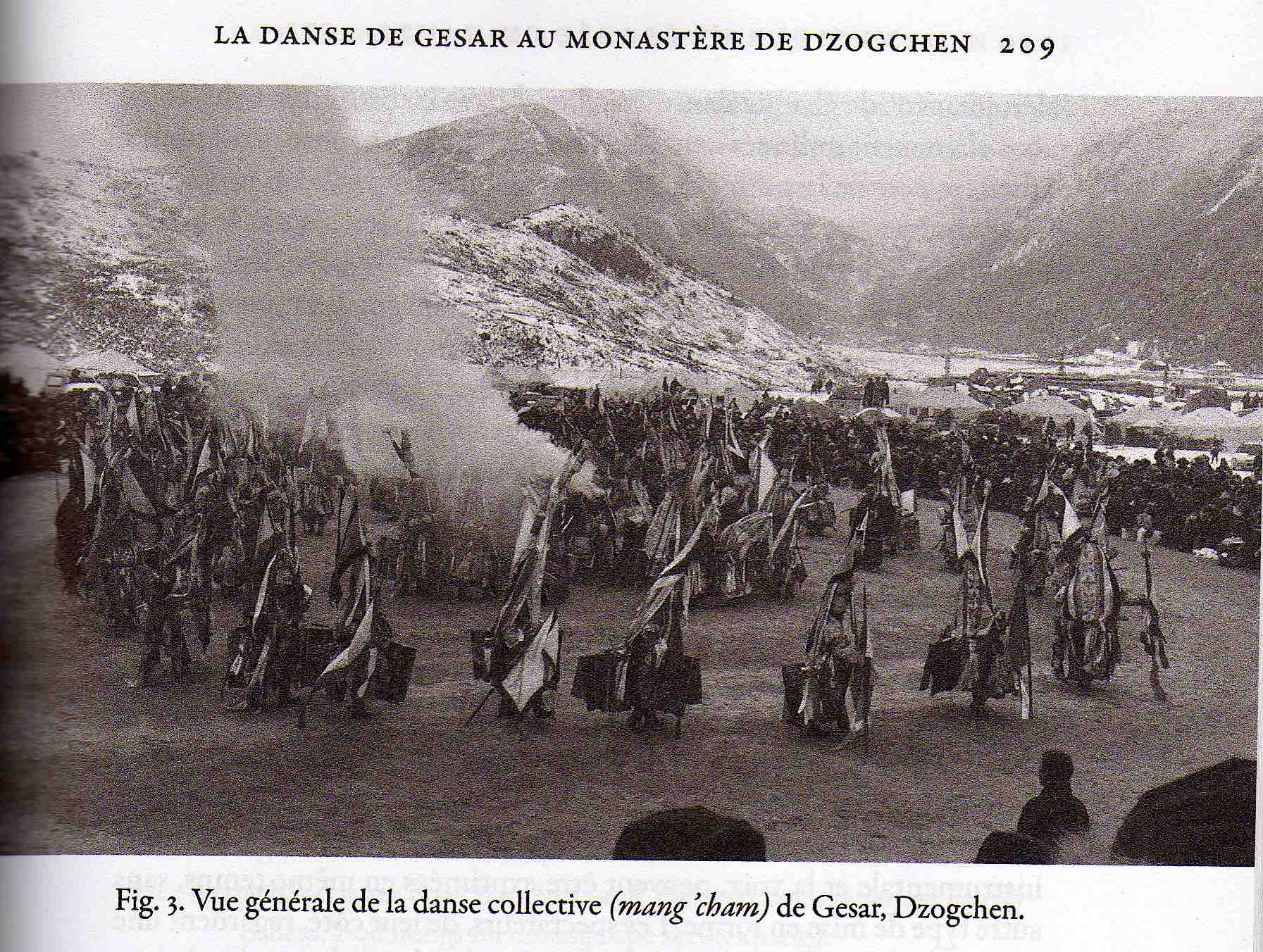

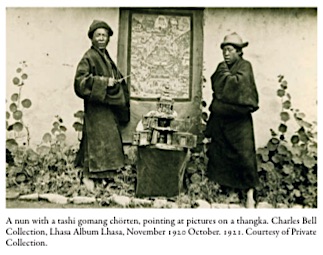

Also belonging within this diverse rubric are the drekar (in Chinese, zhega 折嘎: see

Also belonging within this diverse rubric are the drekar (in Chinese, zhega 折嘎: see