In my summary of Guo Yuhua’s fantastic book on a Shaanbei village, I mentioned the blind bard Li Huaiqiang. The complex fortunes of these bards under Maoism and since the reforms require a nuanced approach, and deserve a separate post. [1]

As I edit my old material from around 2000, I’m aware that fieldwork is always of its time. I haven’t sought to update it, but the period since then will also have seen rapid change—which I discuss further below in my review of a more recent book.

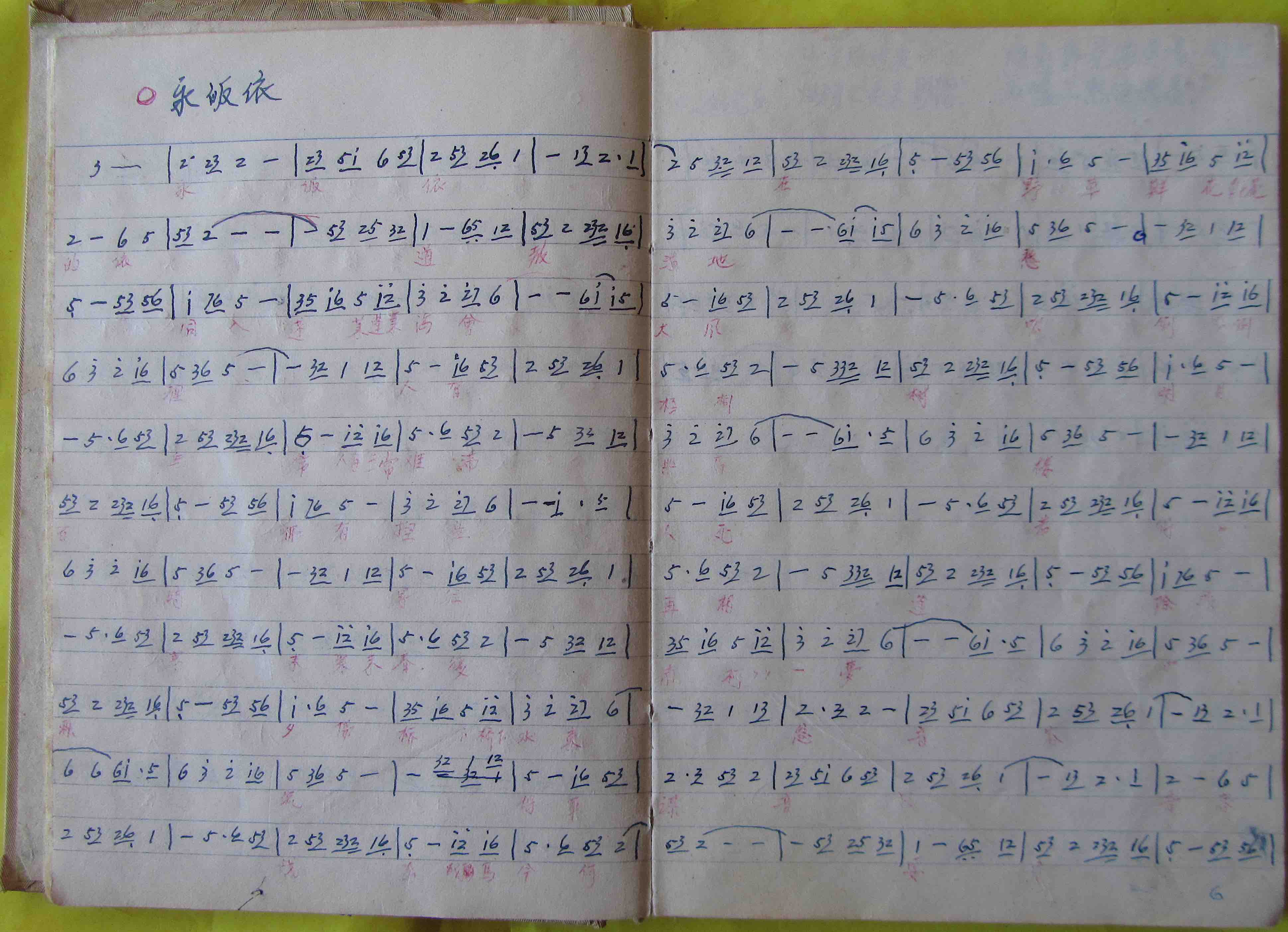

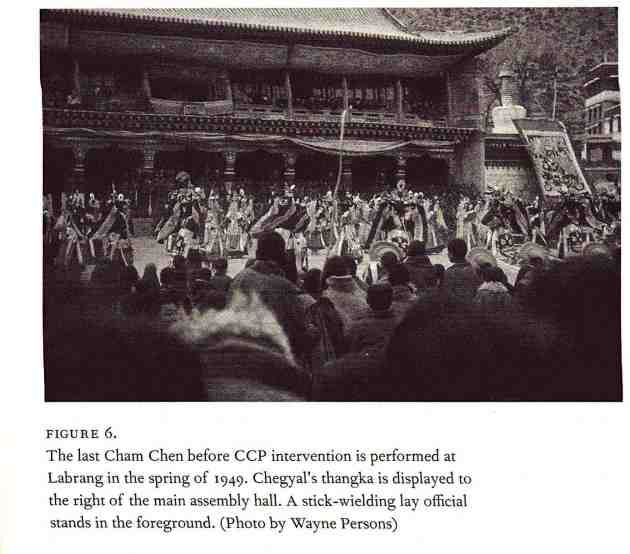

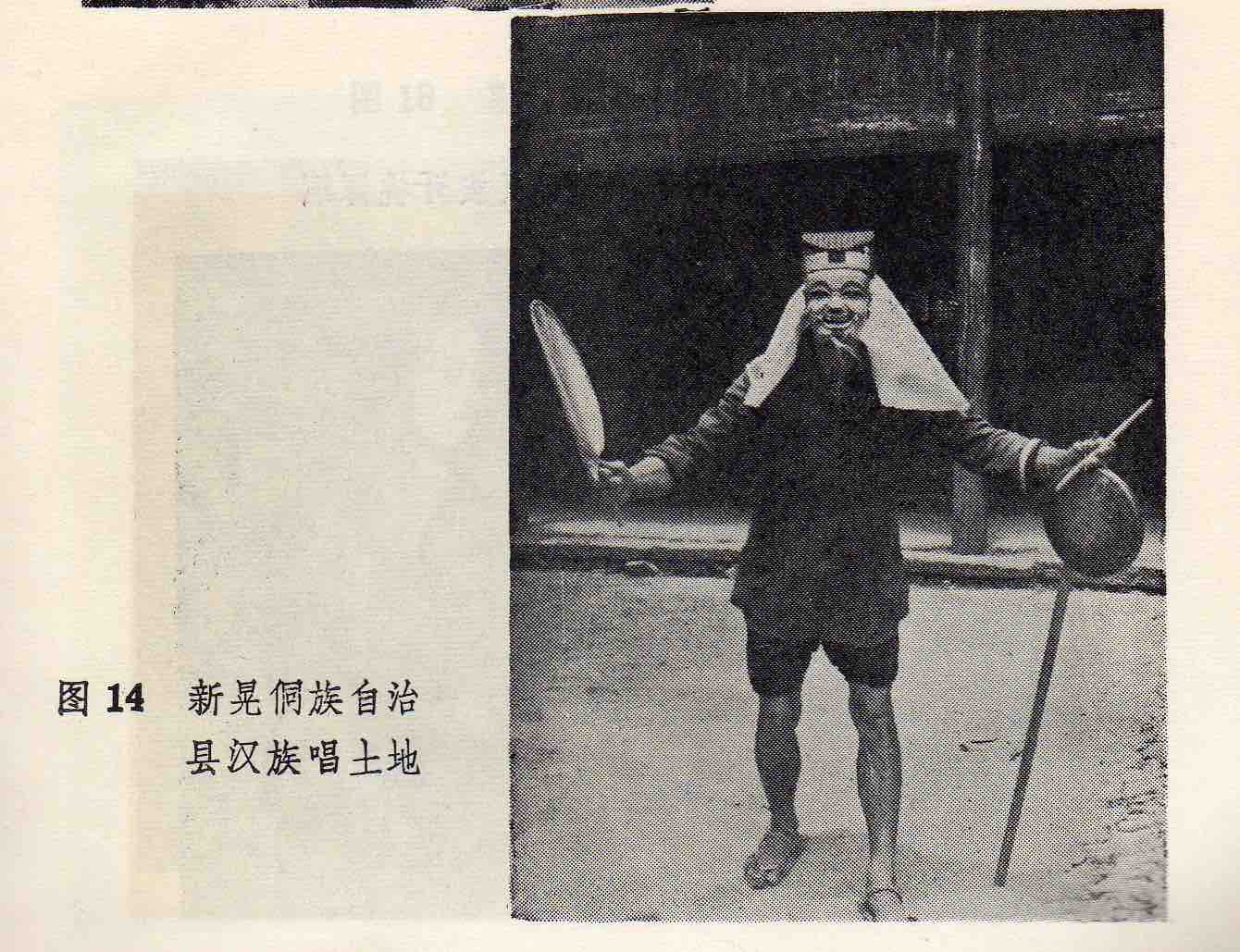

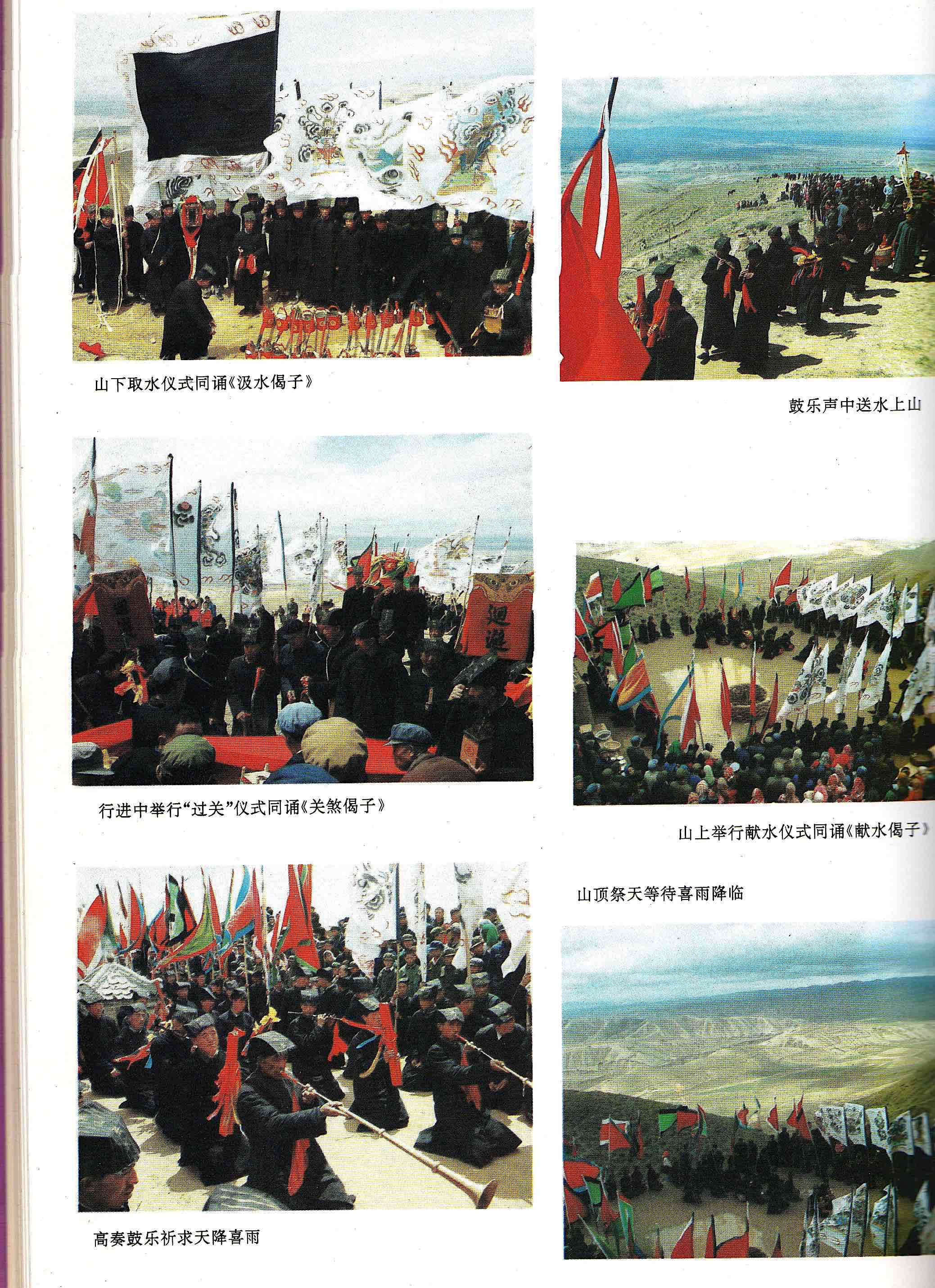

Sighted bard Li Wenjin performs a “story for well-being” to protect the son of the host family, first inviting the gods in the courtyard and then narrating a sequence of stories before the altar inside the cave-dwelling.

See DVD §C4 with my Ritual and music of north China, volume 2: Shaanbei,

and pp.83–4 there).

Photos: Guo Yuhua, 1999.

Introduction

In Shaanbei, as in much of rural China, while many blind men earn a living by taking up the shawm (on which see my post on Guo Yuhua, and here, as well as this post on north Shanxi), others have also long served as protectors of children, acting as godfathers and healers, and telling fortunes—as well as singing “stories for well-being”, accompanying themselves on a plucked lute and clappers, a kind of one-man band. They are itinerant, going by foot over quite a wide area.

Though in decline since the 1960s, the bards appear to have adapted rather little in context or sound. Under the Maoist collectives, some spent brief periods being taught new stories in the county-town “propaganda teams”, but this hardly affected their repertory or performing contexts. Since the 1990s, the popularity of the genre has been further threatened by the media of TV and pop music; and little bands now increasingly supplement the solo performers.

Social background

Blind bards also tell fortunes, cure illness, and act as godfathers—occasions when they do not necessarily perform stories. As godfathers they perform ceremonies protecting children (including hanging the locket, the annual Crossing the Passes ceremony at temple fairs, and opening the locket). These ceremonies have doubtless become rather less common since the 1950s, though neither campaigns against superstition nor any gradual improvement in healthcare entirely explain this.

Li Huaiqiang, in his 70s, had hung the locket for three or four hundred children; Guo Xingyu, in his 50s, for “over 290”.

Like geomancers and mediums, the blindman performs healing in a ritual called Settling the Earth or Settling the Earth God. For this he recites incantations and depicts talismans, but does not perform stories.

These occupations were a lifeline for males only: the fate of blind females was pitiable.

Occupations for blind men in Shaanbei

- begging (yaofan 要饭)

- playing in a shawm band (guyue 鼓乐, chuishou 吹手)

- telling fortunes (suangua 算卦)

- exorcism / healing (antushen 安土神, zhibing 治病)

- hanging the locket (baosuo 抱锁, daisuo 带锁), opening the locket (kaisuo 开锁), Crossing the Passes (guoguan 过关)

- narrative-singing (shuoshu 说书).

Contexts for narrative-singing

- Stories for vows (yuanshu 愿书), to fulfil a verbal vow (huankouyuan 还口愿):

household (jiashu 家书), for well-being (ping’an shu 平安书)

temple fairs (huishu 会书: miaohui 庙会)

parish (sheshu 社书)

- less common: weddings (hongshi 红事), moving into a new cave-dwelling (nuanyao 暖窑), going off to the army (canjun 参军), official meetings (jiguan 机关).

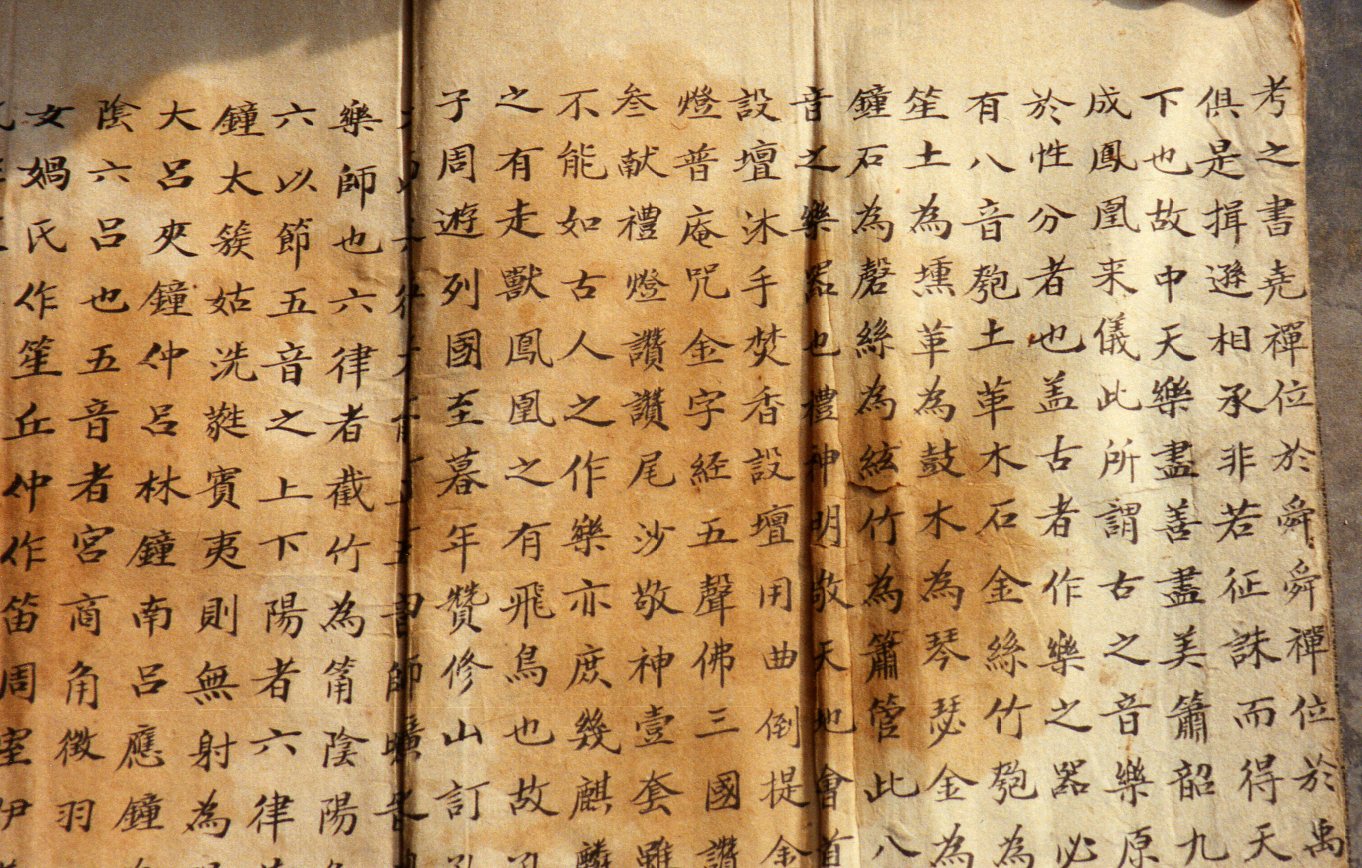

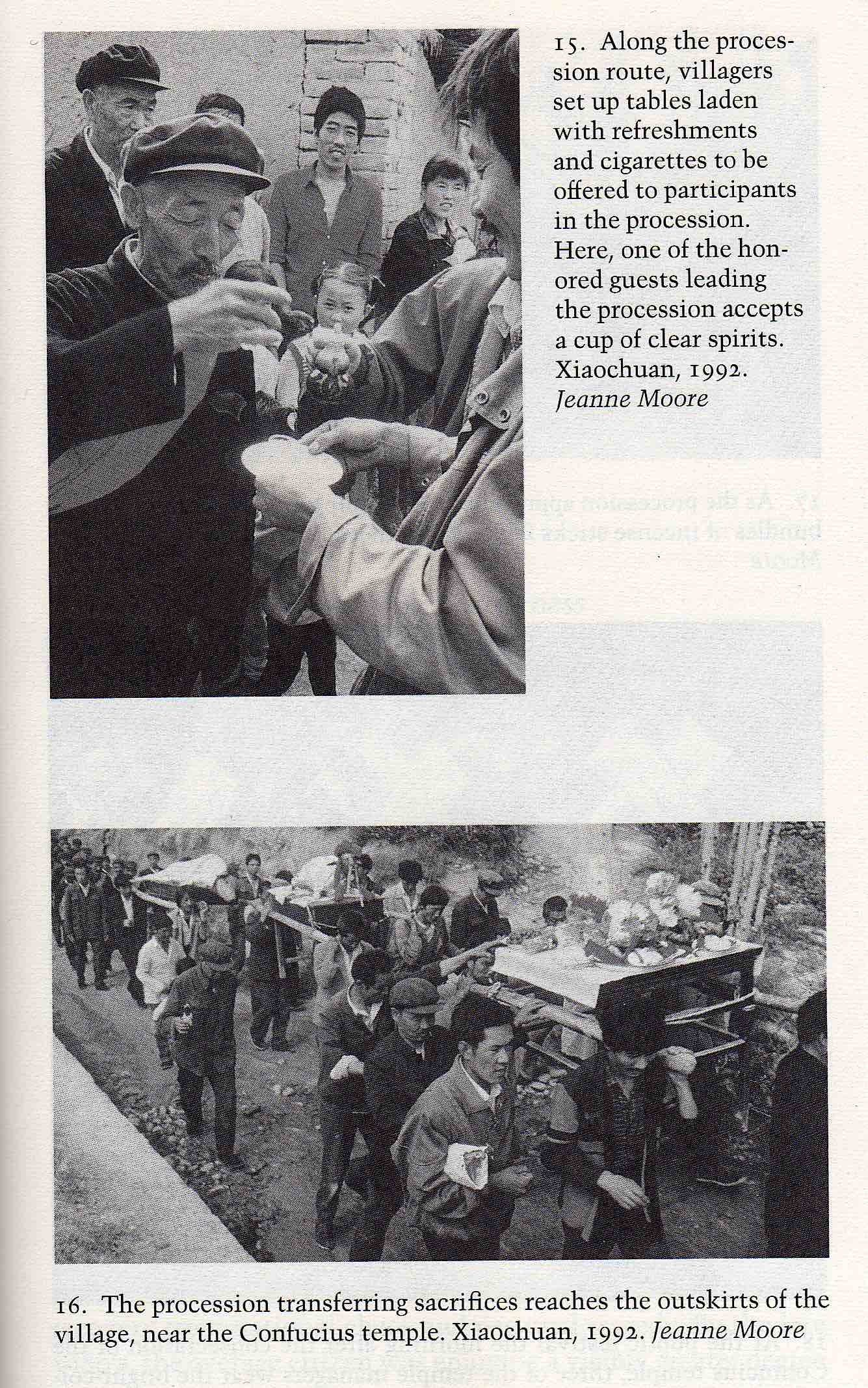

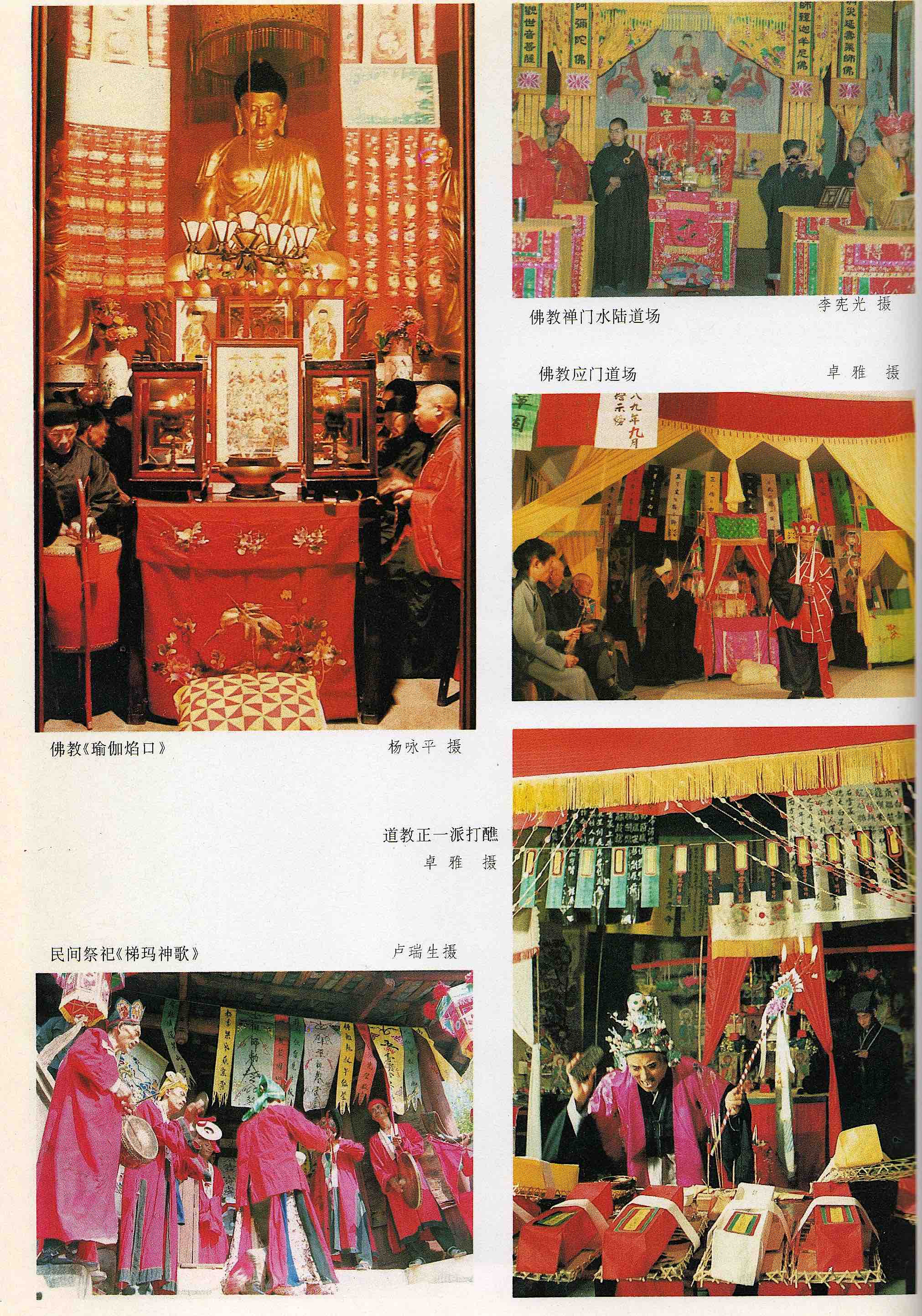

Ritual equipment, stories, and music

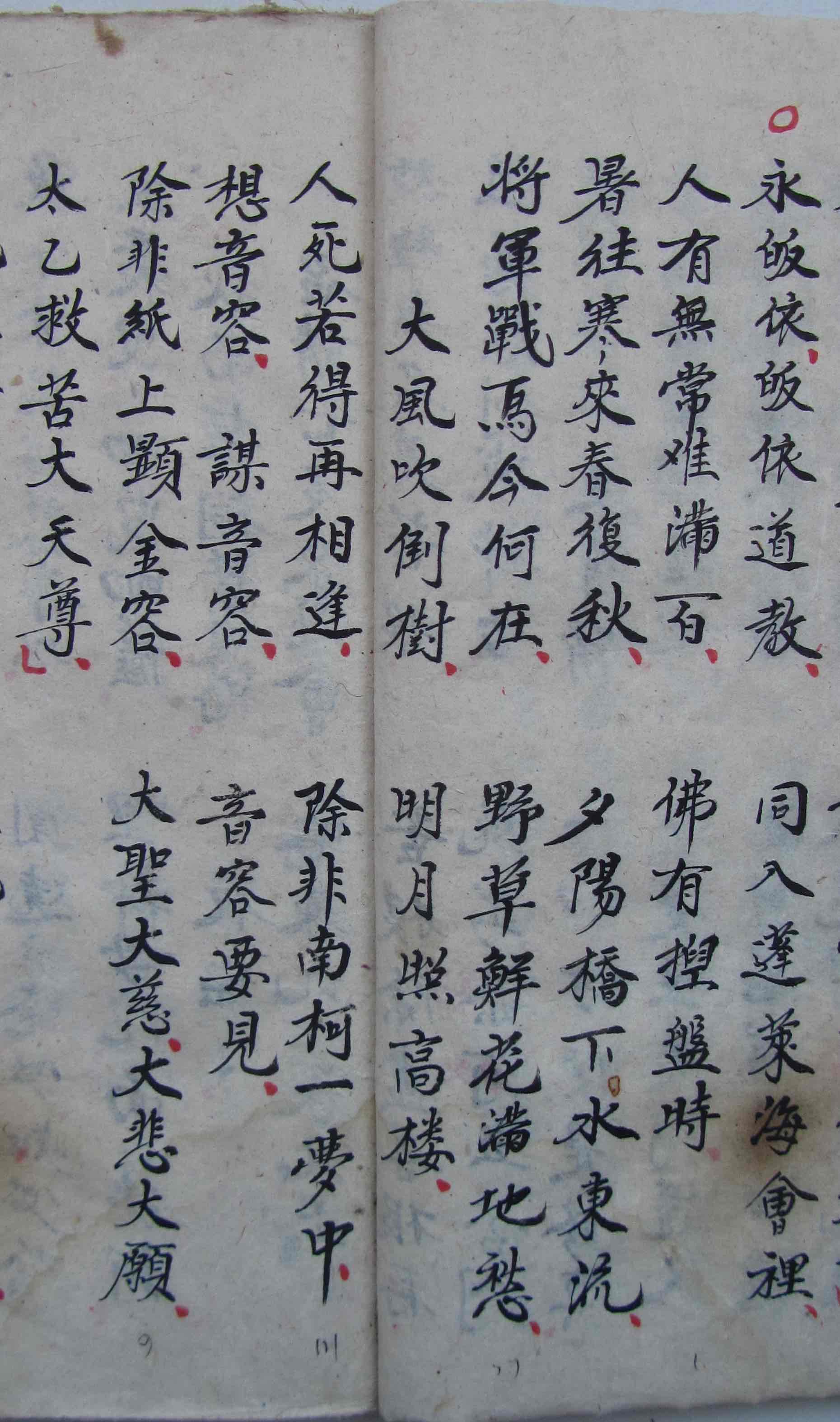

For the narrative-singing contexts, the bard performs before a small temporary altar. Inscriptions for the gods and family, rectangular paper “god places” with a triangular head, mounted on gaoliang stalks, as well as changqing yellow paper streamers, are inserted into one or two rectangular bowls filled with grains of millet or corn. Before the altar are placed a lit candle, small bowls to hold incense and burn paper offerings, and offerings such as dough shapes, biscuits, dates, fruit, peanuts, cigarettes, and cups of liquor.

Li Huaiqiang makes streamers, 1999.

Li Wenjin’s altar, 1999.

The altar is placed on the family stove or on a table; for the rituals to invite the gods and escort them away at the beginning and end of stories for well-being, it is placed on a table in the courtyard outside. Li Huaiqiang, though blind, prepared the changqing streamers himself; someone sighted and literate has to be found to write the inscriptions. Incense and paper are burnt before the altar periodically throughout the performance.

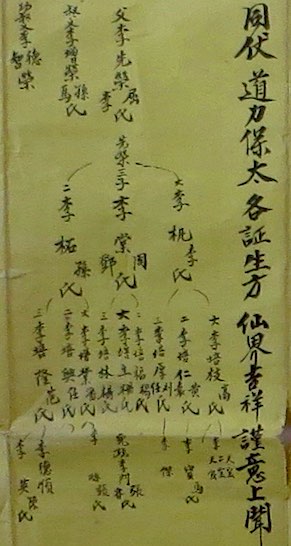

The bard takes with him a red cloth bearing the titles of a pantheon of gods. When not in use it is rolled up and kept in the bard’s bag. The cloth is unfurled and placed upright behind the altar, supported by two sticks inserted into a sleeve at either end of the cloth.

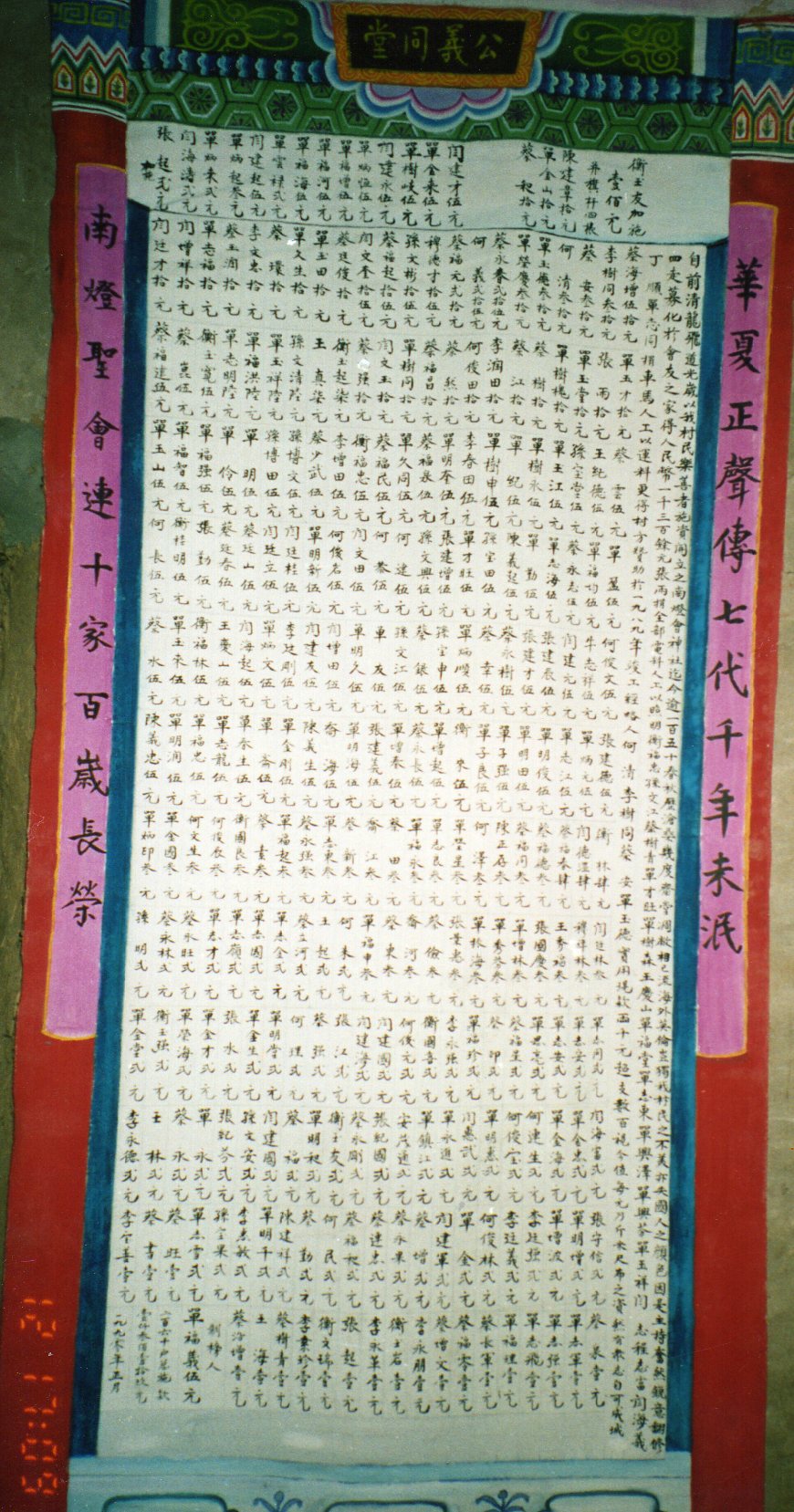

Cloth pantheons:

(left) Li Huaiqiang, 1999;

(right) Xu Wengong, 2001 (for a list of these gods, see Zhang Zhentao, Shengman shanmen, p.356).

Stories overlap with opera plots, relating historical tales of love, official success, solving of crimes, famous battles, and righteous protest—all familiar in Chinese fiction since the Ming dynasty, and often referring to still earlier times. Like opera, these stories have long been a dominant form for poor people to learn of history, legend, and morality, only being challenged by schooling since the 1950s. Schooling even now is quite elementary, though TV and pop music are doubtless replacing traditional stories for entertainment.

Indeed, bards’ stories are like a cheaper, more portable version of opera that can be brought into the home to bring good fortune to the family. Like opera (and indeed TV soap opera), stories may be performed in sections at successive sittings—commonly three episodes (huihui).

Bards improvise phrases on the basis of a well-known story—as He Guangwu observed: “We respond to the changes on the spur of the moment (suiji yingbian 随机应变), the lyrics aren’t fixed and dead (dingsi 定死).”

The solo performer accompanies himself on a plucked lute and usually two percussion instruments attached to his left leg and right hand. He may rest his right foot on a low stool, and drapes a towel over his shoulder to wipe sweat from his face. The plucked lute is either unfretted three-stringed sanxian (known as xianzi) or the fretted four-stringed pipa; the sanxian is most common, the use of pipa declining drastically in this area since the 1980s.

This rare form of pipa (see below), held less vertically than the “modern” pipa, and played with a plectrum, was a major discovery, reminding scholars of the Tang dynasty pipa. As was the trend through the 1980s, they were keen to conjure up “living fossils” and evoke the glories of ancient dynasties, but they mustered less publicity for this supposed relic of the Tang pipa than did scholars of nanyin in southeast China.

Han Qixiang and the training sessions

As with many other genres in China, the national reputation of narrative-singing in Shaanbei rests largely on one performer who came to the attention of cultural cadres and was cultivated by them. Han Qixiang (1915–89), dubbed “China’s Homer” but redder than red. The Party’s model blind bard in Shaanbei during the Yan’an period.

from http://www.confucianism.com.cn/html/minsu/15021455.html

In my book I outline his career, trying to read between the lines of hagiographic Chinese accounts on the basis of the 1993 article

- Chang-tai Hung, “Reeducating a Blind Storyteller: Han Qixiang and the Chinese Communist Storytelling Campaign”, Modern China 19.4 (1993).

From 1945, Party ideologues went to some lengths to reform storytelling with a network of training sessions. After the national “Liberation” of 1949, every county government throughout China set up an arts-work troupe, which soon metamorphosed into an opera troupe; some county authorities further set up a narrative-singing artists’ propaganda team (shuoshu yiren xuanchuandui). These narrative-singing teams were less permanent (and much less costly) than the opera troupes; they held training sessions before dividing into smaller teams to go off on tour round the villages. Bards were lodged together, sometimes for a few months but often for just a few days, and even if they could remember the new stories, they remained reluctant to perform them once they went on the road.

Apart from Han Qixiang, another blind performer mentioned in the 1940s as creator of new stories is Shi Weijun (b.1924), who organized training sessions for bards around Suide county. Blind bard Guo Xingyu (see below), himself no simple official mouthpiece, hinted that Shi Weijun found it hard to adapt to official demands after Liberation. “But then he gave up—he didn’t even want his wages, he lost his standing, and went off on his own to tell stories.” He was clearly reluctant to take part in official events.

We can discount the rosy official image, but even the candid local scholar Meng Haiping recalls the period before the Cultural Revolution as a golden age for the blind bards, with county Halls of Culture organizing them into teams and issuing permits, so that district and village leaders had to receive them, hosting and feeding them—an unprecedented and welcome way to guarantee their “food-bowl”.

Conversely, if the state now acted as the bards’ patron, their richer patrons had disappeared, and their poorer ones were becoming wary of inviting them; temple fairs and “superstition” were under threat. Many bards were not recruited to the teams or were unwilling to join, and even those who did take part did so only intermittently. Although those not registered in the teams were not given permits, they still managed to perform, relying on the old contexts such as “stories for well-being” and godfather duties. But the climate was changing: as the power of campaigns sunk into people’s consciousness, they would have been increasingly nervous of inviting bards openly.

Even those bards who did spend periods in the official teams learning new stories continued to earn their living from more or less “feudal superstitious” contexts. You couldn’t perform new items for hanging the locket, or as stories for well-being.

Party ideologues admired popular oral literature; while deploring its links with superstition, they were unsuccessful in seeking to break such links. The new stories were often based on novellas or opera scripts, and composed with the “guidance” of cadres. As Hung points out, it was hardly a collaboration between peasants and intellectuals—it was never in doubt who was in charge.

It’s hard to assess is how the new stories were received. Even clues in the unremitting hagiography unwittingly give glimpses of constant conflict and difficulties. Han Qixiang composed a new story called “We can’t withdraw from the collective” (Buneng tuishe) (how very true!), reportedly converting peasants who were opposed to collectivism. Having heard that in some Zichang villages women were reluctant to work in the fields, and men reluctant to tolerate them doing so, he composed pieces exhorting them and praising female labour heroes. During the famine of 1959–60 he performed “Turning over a new leaf” (see link in Comment § below) for peasants disgruntled with the paltry goods available on New Year’s Eve, supposedly enlightening them as to how much their lives had improved since the bad old society. Yeah right…

Still, Han Qixiang was a fine performer; even when he told new stories, he would naturally vary them every time, like bards worldwide, and he retained the colourful local vocabulary of bards throughout the area. One cannot merely assess his stories from the page, without being able to witness his performances and those of other bards of the day. Bards I met were less impressed by his technique or creativity than by his good fortune in meeting the right people at the right time and getting onto the government payroll.

So whereas Han Qixiang appears to have been a model “folk artist” propounding Party policies with conviction, most bards in Shaanbei have continued to eke out a living from their traditional exorcistic “stories for well-being”, both under Maoism and since the reforms.

Immortal Li

Among the characters in Guo Yuhua’s book on Jicun is the village’s blind bard Li Huaiqiang (1922–2000, known in the village as “Immortal Li”, Li xian); as ever, my notes benefit from her rapport with him. Visiting his cave-dwelling in 1999, she introduced us and we all sat ourselves down on his kang brick-bed; having explored my facial contours with his hands, he gently held my hand throughout our chat.

Li Huaiqiang was among the great majority of bards (and audiences) not amenable to the new stories. Under Maoism, though he gained a house and a family, his livelihood was reduced; since the reforms of the 1980s he suffered both from the decline in popularity of the art and his own dwindling skills.

Li Huaiqiang was born to a poor family of hired labourers working for the village landlords. Such poor families couldn’t afford to send their children to school, and he attended “winter school” for a mere few days. He lost his sight completely by the age of 10 sui. When he was 15 or 16 sui (c1936–7) his father took him to a blind bard to “learn up the arts” of narrative-singing, “history”, fortune-telling, and healing. Learning stories phrase by phrase was time-consuming and expensive—his father had to scrape the fees together. Li contrasts that ruefully with the ease of young upstarts today who can learn just by listening to tapes.

Li began “going out of the door” to earn a living before he was 18 sui, practising both healing and narrative-singing. He was often in demand to cure illness: when someone’s child was seriously ill, Li could give acupuncture and Chinese medicine. When adults had some irregular illness (xiebing), some bad karma, for which orthodox medicine was no use, he’d find them some special herbs.

Since Yangjiagou was still a landlord stronghold, in the early days Li often performed stories all four seasons of the year for the landlords in the village itself. Such performances—like longevity celebrations, or for the first full moon of newly-born children—often lasted seven or eight days. The landlords had a shrine to the god of wealth in their houses—before it bards would tell their stories, and Buddhist monks would recite their scriptures.

Ritual has always remained paramount for bards like Li. “Poor people (shoukuren) worship the Dragon King Elder (Longwangye), stockbreeders worship Horse King Elder (Mawangye), people in business worship God of Prosperity Elder (Caishenye). When people make vows they invite us to tell stories, that’s how we make our living.” Since vows were often fulfilled in the 1st and 2nd moons, bards were most busy then.

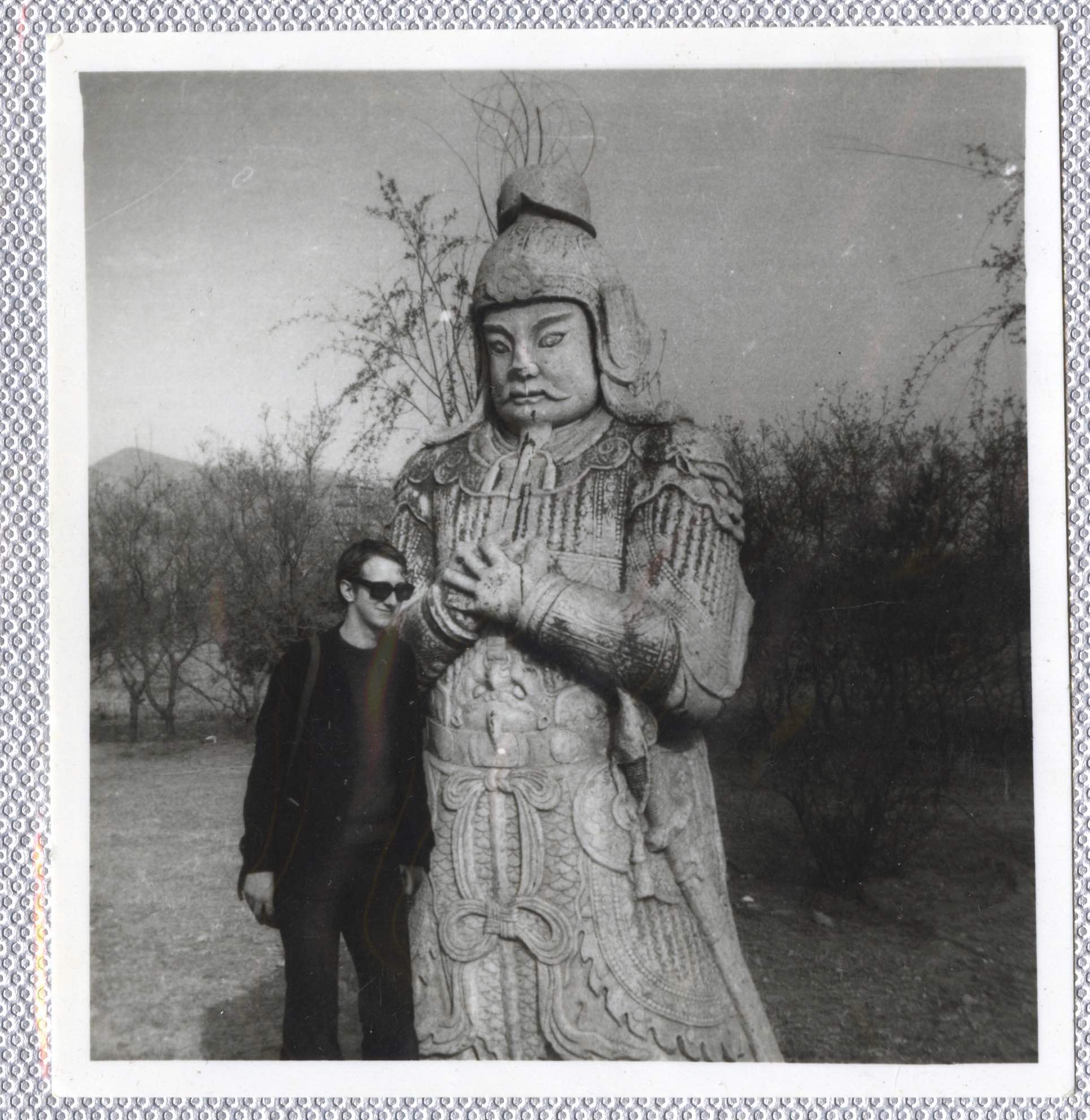

By the 1940s, Li’s itinerant business was taking him—by foot—all over Shaanbei. Recalling the old temple fairs, he mentioned the two most famous, still very active now: “I used to go to Baiyunshan for over twenty years, I even went once after the end of the Cultural Revolution. I used to go every year, there were kids there that I’d hung the locket for.” Li performed for the small temple fairs in his home village too, notably the 4th-moon fair at the Pusa miao temple. The temple fairs in the neighbouring hamlet of Sigou were planned best, and were popular; people liked listening to narrative-singing there.

Li Huaiqiang’s early visits south to the Yan’an region, in 1938 or 1939, were part of his routine itinerant business. He told stories around Hengshan and Bao’an (Zhidan) counties too. “No-one controlled what stories you told then, you could narrate what you liked.”

In 1943, after the Suide–Mizhi area was taken over by the Communists, Li found himself unable to make a living there, and went off to Yinchuan in Ningxia and nearby Xichuan. The Nationalist officials loved listening to stories—bards were invited to their quarters. They could travel freely then—only later, when the Communist–Nationalist collaboration ended, did the roads become impassable.

Still, his assessment of the Red and White areas was ingenuous. “It was just the same under the Communists and the Nationalists. Under the Nationalists it was easy to earn money, people liked to listen to stories. After the Communists took control over people, not allowing superstition, at least there was provision for us disabled people, there was relief. So things were the same.” But he did remark, “In the end the Communists came along and broke all the temple fairs up, so there was nothing left.”

I wonder how many bards chose to seek a living in either the Red or White Areas. Evidently old stories did not suddenly vanish throughout the Yan’an countryside. The Yulin region was a seesaw area between the two sides, and most local leaders would, as yet, be broad-minded about traditional forms. We can’t judge, but it is worth challenging the propaganda. And having blithely equated “new stories” with items supporting the Communists, I wonder if bards in the Nationalist areas performed new stories opposing the Communists.

Li Huaiqiang dismissed our queries about the officially-organized groups—he had only the vaguest recollection of this experience. It might have remained an exciting moment in his life distinguished by its uniqueness—but apparently hadn’t. Li went on:

From 1945 they summoned all the blind bards to meetings—they weren’t allowed to sing old stories any more, they had to sing new ones. I studied them and then forgot them all—well, I basically didn’t study them! When you go out [on business], the common people don’t listen to that stuff! New stories aren’t good to listen to—people don’t like listening to new stories, they like old ones! I could never forget the old stories I learned when I was young, though. I can tell twenty or thirty stories. When you went out in the old days there was business, you could count on it—who’d have thought it would all come to an end?

He knew of Han Qixiang but didn’t hear him perform or meet him. “That Han Qixiang, he got onto the official payroll. Oh yes, people in our business all know about Han Qixiang. In the Yan’an period people reformed it into new stories, but they didn’t control us lot who narrated old stories, we just went off round the countryside narrating on our own.” He knew that some performers sang for political meetings, but didn’t admit to doing so himself.

Li Huaiqiang was lucky to find a wife:

I was 24 when I got married [c1946]. They came to take conscripts—people stuck to their old habits, no-one wanted to go off, but they forced them. But us blind people, we couldn’t go off to the army, no-one wanted us—that’s how I got a wife. People were afraid of joining the army, both sides were taking people off, no-one dared go, as soon as you went off you’d get killed. If it was today I couldn’t get married—now it’s hard enough for sighted men to find a wife.

During land reform there were meetings all the time. The Communist Party controlled people, eliminating superstition. When they wanted to hold a meeting they first summoned a bard to narrate a [new] section, so everyone turned up—then the bard sang the old stories that people liked.

This was a common theme, of great significance for our understanding of the Maoist period. The bard would attract people to turn up for tedious political meetings, and satisfy the demands of political expediency by performing a brief political item first, before the fun began. Scholar Meng Haiping recalled: “Both old and new stories were heard then. Until 1956, they began with a short section with new content, then moved onto the old stories like ‘The story of five women reviving the Tang’ (Wunü xing Tang zhuan).”

Li Huaiqiang originally lived in a miserable cave-dwelling made of earth, but after land reform, he was helped to “buy” a comfortable cave-dwelling right at the top of the village from the former landlords, which had been servants’ quarters. The landlords also had to “sell” him their precious sanxian banjo, which he bought for one dan of grain.

If in that sense Li was able to profit from the overthrow of the landlords, he soon suffered from their demise. “We were allowed to narrate stories in the early days after Liberation, but people’s consciousness was raised, people had studied a lot of books.” I didn’t care to argue with him there, so he went on, “They said narrative-singing was boring, so there was a lot less of it—it got less all of a sudden with the collectives [from the mid-1950s]. People like us just tilled the fields, told fortunes, we could just about get by, the state gave us relief. We couldn’t just die off—some people were given relief, some were put in old people’s homes, some with skills could go out and heal illness and tell fortunes.” And he was still taking large numbers of godchildren, whose parents’ regular little gifts always presented a lifeline.

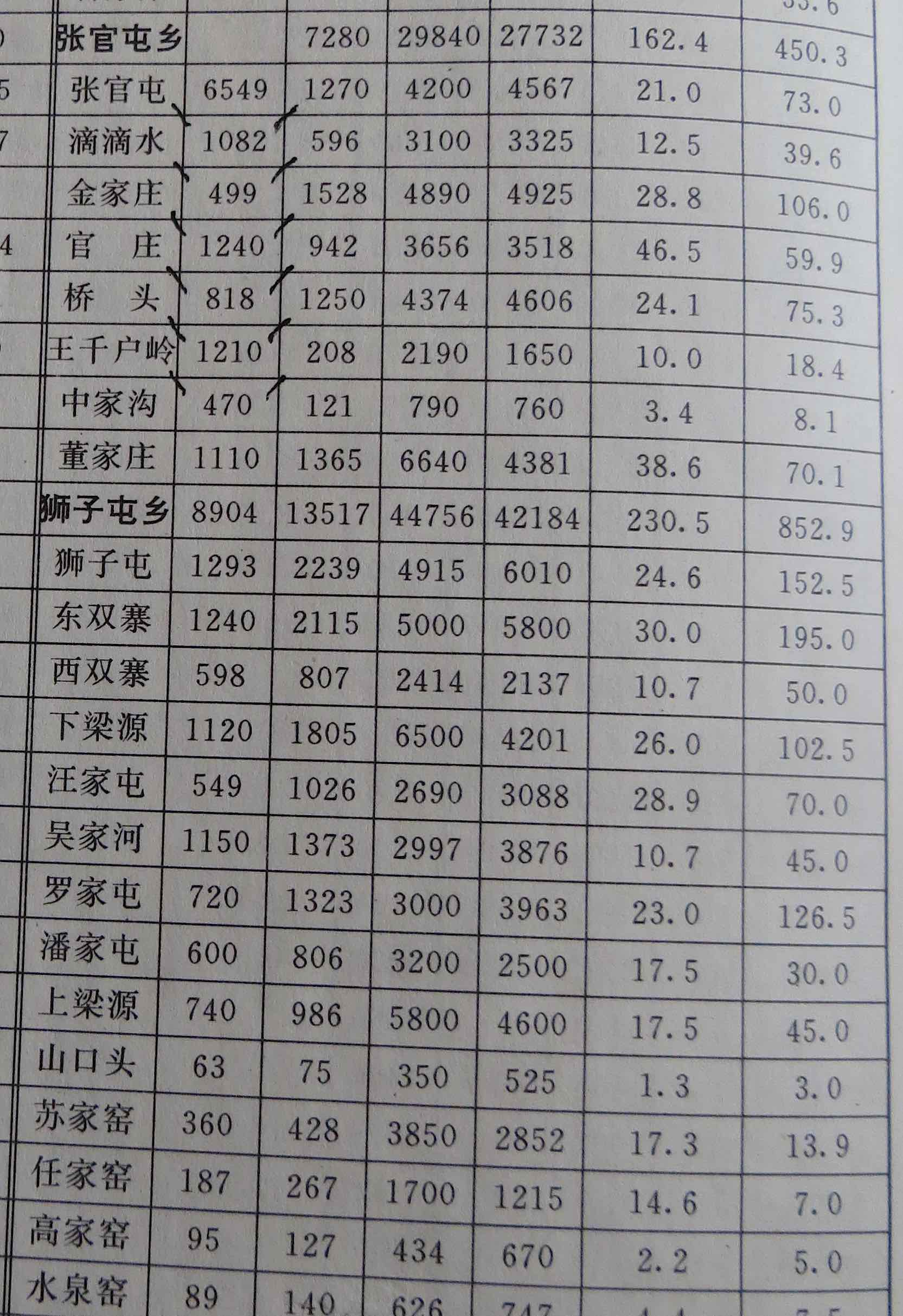

If Li Huaiqiang was unaware of it, the Mizhi county authorities were attempting to organize bards. Gao Zhiqiang, former chief of the county Hall of Culture, recalled, “The county first set up a narrative-singing team in the early 1950s, organizing over twenty blind bards, training them all together to sing new stories. The Hall of Culture issued them with performance permits, which meant that the district and village authorities had to host them—that resolved blind men’s problem of livelihood.” But the teams never controlled blindmen for long.

Li Huaiqiang, who had never belonged to a team or performed in a group, still relied on a minimal handout from the village government to survive; with his wife and five children, times were desperate. “In the Cultural Revolution they didn’t invite us bards any more, it just stopped. But people like us still went out—mostly to tell fortunes, not so much to narrate stories.” And he sometimes sneaked out to hang the locket for children in exchange for “a couple of little coins”. Li was soon branded an “ox demon and snake spirit”, accused of feudal superstition. They took his manual off and burned it; they took his sanxian banjo away too, but he got it back after half a year. “Pesky kids, coming to our houses to get us to hand things over—if you did, then you were let off, if you didn’t then they paraded you through the streets.” Li was only paraded once. The only time he could recall when the authorities regulated narrative-singing was in the year of rebellion (zaofan) of the Cultural Revolution, when all the brigades had to organize blind bards into narrative-singing teams to go round and make propaganda, the county Hall of Culture taking a cut.

The reform era

In Shaanbei, as elsewhere in China, as the commune system began to be dismantled from the early 1980s, traditional culture revived more openly. Bards had been active throughout the commune period, both in and out of the new teams; if the old contexts and stories had never died out, after the “rotting of the collectives” there was no longer such need for collusion or duplicity. As Li Huaiqiang recalled, “As soon as Mao Zedong died, they stopped controlling us bards.” But like other traditional performers, they were soon competing with new economic pressures, TV and pop music taking their toll: where Maoism had failed to marginalize tradition, capitalism looked like succeeding.

Despite his privations under Maoism, he warmed to the theme:

Society’s different now, people have “turned over a new leaf”, reforms and all that—too much reform, it’s all gone too far…

Ebullient local pundit Meng Haiping had a perceptive comment:

In those days [under the communes] they tried to destroy traditional culture, but couldn’t; now they don’t control it any more, but it gradually declines anyway. 1984 to 1990 was the best period. Ever since the great wave of economics started, culture has been dying out.

The agenda of the cultural authorities hardly changed, even if state policy would never again be so “hard”: they still sought to teach the bards new stories to spread education about party policies, and they still aspired to both “controlling” and “looking after” the bards—ambivalent meanings of the term guan 管.

By the late 1990s Li Huaiqiang, quite frail in his old age, was less active as a bard. Lucky enough to have found a wife during times of war, Li has two sons and three daughters; but the family has remained poor, and the sons have been unable to find wives. In 1999 Li performed for the 4th-moon temple fair in his village, and he still did the occasional story for well-being for families fulfilling vows. But he told us: “I’m almost without business these days, 80% of my work is gone. Most temple fairs don’t have narrative-singing any more. These days people read books a lot [surely he overestimates this!]—the state doesn’t control it any more, people just don’t want to be away from work. They’ve got TV and recordings too now.” He used to perform for audiences of 80 or 90 people, but now it’s only for around 20 or 30, mostly elderly. “I can’t keep up.” This didn’t apply generally to narrative-singing in the whole area, but to Li in particular—elderly, frail, and no longer a gifted performer.

In the exceptional conditions of Yangjiagou, the occasional visit from Japanese tourist groups, Chinese and foreign scholars, and visitors to the memorial hall to Chairman Mao’s 1947 sojourn, allowed Immortal Li to supplement his meagre income: “They always get me to perform when someone comes.” But his main income still came from his godchildren, as it had done under Maoism. While we were in the village, one of his godchildren’s children was getting married, and when he paid a visit he was given 20 kuai; when he left they gave him mantou steamed buns, and later they gave him some clothing.

We took him to the cave-dwelling of our host Older Brother, the sweet blind shawm player, to perform a “story for well-being” for the family, as usual inviting the gods outside in the courtyard before telling a story indoors. Though his skills were in decline, it was a memorable occasion.

Li Huaiqiang died in July 2000, falling from a narrow mountain path while on his way to another village to hang a locket. Since his death, other itinerant bards occasionally stop off to perform in the village.

He Guangwu

He Guangwu (b. c1932) is a semi-blind bard from a village west of the river, south of Mizhi town. He began to lose his sight when 15 sui (c1946), so a couple of years later he began “learning the arts” with a master from Zizhou county, mastering a dozen traditional stories—although this was supposedly a climactic period for the new stories, the old stories were being transmitted as if nothing had changed.

He married when 21 sui. Their families arranged the match; his betrothed lived in a village only two li away, but they wouldn’t let her see him, and she only discovered his disability at their wedding. Now she jokes about it and is evidently happy that the family is relatively prosperous with many great-grandchildren; we didn’t like to press her on how it had seemed then.

He had taken part in training sessions in 1955 and 1964, but his concept of his livelihood barely took official contexts into account.

His family has done well since the reforms. He is active over a small area, proudly claiming to be well known within a radius of 20 li (10 kilometres), and he hasn’t taken any disciples. But he is busy. “People still invite me, and I still go. For temple fairs, or if a donkey isn’t eating its fodder, or if a family member is on a long journey, you must invite a ‘story for well-being’; and I tell stories for opening the locket, weddings, moving into a new cave-dwelling, and sons going off to the army.” He is also busy telling fortunes and healing.

With He Guangwu, 2001. Photo: Zhang Zhentao.

In 2001 we found He Guangwu at a small temple fair at Jijiashigou, near his home village. He had agreed to tell fortunes for a family there to help them overcome adversity, and hadn’t brought his sanxian. He agreed to tell a story for us back at his home if we took him back to the temple fair later.

Tian Zhizi

We also visited Tian Zhizi (b. c1933) at his son’s home in a little town south of Zizhou on the road to Suide. He had belonged to the Zizhou team, and also studied in the Suide team. “My eyes were no good from young—I began studying narrative-singing in 1944. My master was Wang Jialai from Zizhou county. When I learned I lived at his house—his fee was 3 dan of grain per year, and I learned for three years.” Through the War of Resistance and the War of Liberation—precisely the period when the new stories were supposedly in the ascendant—Tian supported himself by curing illness, reciting incantations, and depicting talismans.

I began telling stories in 1951, and in 1952 became chief of the Zizhou blind people’s propaganda team, which had been formed the previous year. I was chief of the team for three years; it had over 60 members. Between 1952 to 1956 I studied new stories at the Jiuzhenguan hall in Suide.

Their boss was Shang Airen, an influential cultural official in Shaanbei. Despite my suspicions, Tian recalled,

In the 1950s the peasants loved hearing new stories. The main ones I learned were “The outstanding troupe member”, “Zhang Yulan takes part in the election”, “Opposing shamans”, “The tobacco pouch”, “Mother Gui makes shoes for the army”, and “Wang Piqin takes the southern road”.

Still, through the 1950s and 60s, while the bards from the team sometimes went on tour in small groups, Tian usually went round on his own. When he was 28 sui (c1960), Tian married a girl from the same town—which he claimed was “free love’” not arranged. In 1962 he spent a period working in Yan’an with none other than Han Qixiang, earning 36 kuai a month. Later he resigned and returned home, still making a living as an itinerant bard, also telling fortunes, hanging and opening lockets—by 2001 he had over 200 godchildren.

He went on, “I have 28 disciples in all, eight in Wubu, four in Yulin, two in Shenmu, also in Yan’an, Ansai, and Bao’an [Zhidan]. I took some disciples while I was at Yan’an in 1962, others stayed at my house to learn.”

Unusually, the Cultural Revolution was a significant period of activity for blind bards, who continued to perform both in their traditional contexts and in the state groups. The latter now had a new lease of life as “Blind artists’ Mao Zedong Thought propaganda teams”. In Mizhi county, the Hall of Culture organized a dozen bards into one such team, touring villages, mines, and schools—villages without electricity, mines where accidents were routine, schools with few tables or chairs, and the whole population constantly hungry and demoralized, if you will forgive me for reminding you.

“In 1972 I was mainly taking disciples in Wubu, ‘cos the Wubu Hall of Culture invited me to come to train members for their propaganda team.” Though it was ever harder for bards to perform without the sanction of the teams, popular taste still appeared to require an escape from the relentless revolutionary diet. Tian Zhizi had claimed that the new stories were popular in the 1950s, but “from 1967 [traditional] narrative-singing was forbidden—by that time people preferred old stories, or at least they didn’t like new ones, so we bards told some old ones in the villages on the quiet.”

Other bards also told us that while they couldn’t hang the locket openly during the Cultural Revolution, for those who needed it they still did it, and they still performed in secret in the villages—the people liked to listen and protected them. Geomancers were also still furtively active.

Ironically, perhaps the worst case of penalization was revolutionary Han Qixiang himself, inactive and subject to public criticism throughout the period. As late as 1976, just as the Gang of Four was about to be arrested, he was summoned to perform in Xi’an and criticized, though by late 1977 he was well back on the road to rehabilitation, taking part again in official meetings.

Guo Xingyu

A younger blind bard more able than many to move with the times is Guo Xingyu (b.1951), with whom I spent some time in 2001. His case is quite exceptional among bards I have met, following political trends astutely while continuing to take godchildren and cure illness.

Brought up in a poor Suide village, Guo Xingyu was blind from young. He studied narrative-singing and fortune-telling for ten moons with Wang Jinkao from the age of 12 sui (c1962). He started going out on business when about 16 sui, on the eve of the Cultural Revolution. “When I was young I enjoyed learning everything from my master, curing illness, depicting talismans and chanting mantras”.

When I was just starting out we mainly told old stories, though in public contexts we told bits of new stories. New ones I liked telling, before and during the Cultural Revolution, were “Fuss over an abortion”, “Eliminating transactional marriages”, “The great immortal who eats ghosts”, “Eliminating superstition”, and “The tale of the city youth returning to the countryside”.

In 1968 Guo Xingyu joined the Suide county blind peoples’ propaganda team, which had several dozen bards, divided into three or four sub-groups:

In the 60s we were issued with narrative-singing permits; we had to hand over part of our income to the Hall of Culture as “public assets”—the state also took a certain amount of training expenses, but later that stopped. In the 60s and 70s the whole county probably had about 70 or 80 bards—about 40 or 50 didn’t enter the training bands, they had to tell stories on the quiet.

Guo Xingyu even took part in official festivals in Suide, Yulin, and Xi’an; he was praised by the venerable Han Qixiang. He appeared a model bard in the new mould—little would one think that all the while he was performing stories for well-being and healing.

From 1972 I was head of the blind men’s propaganda team organized by the Suide Hall of Culture. I entered the Party in 1975, and from 1978 I was political instructor of the team. In the 1980s I composed some new propaganda-type stories on the basis of the political needs of the time, mainly things like advertising the spirit of the Party’s 12th and 14th Plenary, and birth control, like “Fuss over an abortion” and “Marrying Late”.

By 2001 the team was moribund. Guo and his (sighted) wife were dividing their time between his home village and an apartment in the suburbs of Suide town. He had rarely performed as a bard since getting heart disease around 1991; now his main livelihood was curing illness by depicting talismans and chanting incantations, and hanging and opening lockets. Relying on his traditional magic, he legitimized it with a fashionably scientific-sounding defence: “magic power is rational (fali you daoli)”.

Guo Xingyu took us to see his blind master Wang Jinkao at his village home south of Suide town (DVD §C3).

With (right to left) Wang Jinkao, Guo Xingyu, and Wang’s son, 2001. Photo: Tian Yaonong.

Wang (known as Niur, b. c1930) married a sighted girl in 1947; they have three sons and a daughter, all peasants in the village. Wang accompanied himself on pipa rather than sanxian. When Guo Xingyu studied with him around 1962 he was running a kind of blind school in Qingjian; he learned in a group of five or six blind boys, whose parents had to pay fees. He was one of few bards still using pipa rather than sanxian.

Wang Jinkao had had minimal contact with the new ethos: he could tell new stories like “Wang Gui and Li Xiangxiang”, but if he had ever taken part in training sessions or belonged to the county team, no-one cared to remember.

As we saw, bards mostly worked solo; even when they assembled for temple fairs and New Year’s festivities, they performed in sequence, not together. But under Maoism, bards were sometimes organized into small groups to perform for non-ritual contexts.

Still, both new contexts and musical innovations remained a minor feature even through the years of Maoism, and after the “rotting of the collectives”, tradition became yet more dominant. Some new stories were still performed—on the birth-control policy, the reform and open-door policy, the private enterprise system. Some county authorities continued their efforts to organize blind performers, even trying entry by ticket. But as prices rose and more modern entertainments became popular, they resorted to more viable money-making ventures like setting up halls for video games, or classes teaching electronic keyboards.

By the 1990s the propaganda teams were virtually defunct. As one cultural cadre told us: “Later the bards didn’t want people to control them, and we didn’t have enough money anyway, so we gave up.”

Blind and sighted bards

Though Han Qixiang mentioned competition between blind and sighted bards when he was learning in the 1930s, narrative-singing in Shaanbei was largely a monopoly of blindmen, and only since the eve of the Cultural Revolution has the taboo against sighted performers been seriously challenged.

By around 2000 it was a fait accompli for sighted men to muscle in on the trade. There were fewer blind people anyway, since health has improved (though still appalling); and they could now receive modest disability benefits, or migrate in search of work as masseurs.

Nor do sighted men fear going blind any longer if they take it up. Half of Tian Zhizi’s 28 disciples were sighted—presumably those he taught since the 1970s. Although one elderly bard commented that the new disabled allowance for blind people makes them lazy, blind performers who are still active rather resented the encroachment on their “food-bowl”. “Originally sighted people weren’t allowed to tell stories—if you’re sighted you can do anything [else].” Now not only can sighted people learn, but they can even learn from tapes, saving them money but depriving senior blind bards of teaching fees.

Scholar Meng Haiping pointed out: “In the old days, bards’ social status was low; now for everyone all that counts is money, social status no longer comes into it.” This was certainly true for trendy young chuishou shawm-band musicians in the towns, but less obvious for the bards. Unlike the chuishou, bards have not spruced up their image so ambitiously, and remain quite modestly paid; nor have they yet availed themselves of the mobile-phone revolution that has occurred since about 1998. Whereas chuishou often ride motor-bikes, bards (even sighted ones) mostly go on foot.

Guo Xingyu:

Now there are sighted bards everywhere—many senior-secondary graduates, not wanting a hard life, go and tell stories. In Zizhou, Hengshan, and Yulin there are a lot of sighted bards, and there are some in Mizhi and Jiaxian too. Now there are fewer than thirty blind bards in Suide, but there are more sighted ones. They began appearing in the 1980s or 1990s, they drove the blind ones away; the blind ones were very angry about it—but the sighted ones had permits too.

He went on darkly,

Now how did that come about, then? Perhaps by bribery. Now blind artists are in great difficulties. There are more of them west of the river, but quite a few of the old artists have died; east of the river their skills aren’t quite so good.

Li Wenjin

I met sighted bard Li Wenjin (b. c1943) with Guo Yuhua in 1999 when he performed informally for staff at the office of the Black Dragon temple (on which see Adam Chau’s fine book Miraculous response), as a kind of advertisement for his arrival in the area. He comes from a village in Zizhou county. Soon after Liberation, in the early 1950s, he studied for three winters in the evenings in the “school for sweeping away illiteracy”. His parents died early, but he only began studying narrative-singing in the early 1980s, with the old blind bard in his village. His master could never find a wife: “when the five organs are incomplete, no-one will follow you”—though most of our blind mentors were exceptions. There was a libretto (benben) that he could follow—even blind performers sometimes owned a libretto. Li Wenjin was active over quite a wide area. He usually sings with his eyes closed—in imitation of blind bards?

Guo Yuhua and temple organizers listen to Li Wenjin, Black Dragon Temple 1999.

A couple of days after meeting him at the temple where we were staying, we bumped into him on our way back there, and he invited us along to hear a “story for well-being” that evening for a family in the nearby village (see photos at head of this post).

Xu Wengong

We met another sighted bard at the White Cloud Mountain temple fair in 2001. Xu Wengong (b. c1948), from a village in Qingjian county, began learning at 17 sui [c1964] from an uncle, so the taboo was perhaps being broken down even then. He has never taken part in any county-organized teams, or learned new stories. During the Cultural Revolution he was protected by villagers as he went round performing and hanging lockets on the quiet.

Many pilgrims attend the temple fair under the auspices of a dozen or so regional associations, each with particular allegiances among the many temple gods, sponsoring different daily rituals. Apart from the daily performances of opera, bards perform in a less public and commercial arrangement that is also typical of Shaanbei temple fairs. One evening we visit the cave of the Zizhou, Qingjian, and Ansai association where Xu Wengong was performing.

He comes to this fair every year as part of this pilgrim association, in order to fulfil a vow. “My father was a model labourer, and was head of this association”—note this typically casual link between Communist and traditional authority. “He came here to take part in the rituals and made a vow, because I’d had stomach disease for twelve years, and sure enough I got better. So I’ve been coming here to fulfil the vow every year since the temple restored, to revere the great god Zhenwu; I come here to avert calamity.” Some other bards also come to the temple fair not to make money but to fulfil vows.

There is no need to “invite the gods”, since they are already present, but on the left of the cave, as you stoop to enter, is an altar behind which the bard’s red cloth pantheon is displayed (see photo above). Individual pilgrims periodically burn paper and kowtow before it. Xu Wengong performs opposite the altar, the pilgrims sitting on mats at the rear of the cave, listening intently. They consist mostly of men over 50, but even those over 60 were brought up largely under Maoism. Yet such senior men entirely represent tradition; ritual associations like this surely represent a kind of passive alternative to government control.

Xu Wengong, Baiyunshan 2001

Old and new stories

Despite the propaganda surrounding Han Qixiang, not only does no-one value new stories now, but few recall them being popular even under Maoism. He Guangwu recalled, “In those days, usually we’d tell a section of a new story first and then tell an old one.” Other bards like Li Huaiqiang had no time for new stories at all. He had heard “Smashing superstition” on tape at a villager’s house, but “people don’t like it, it’s not good to listen to—you can’t sing stories like that for families, only for big meetings where tickets are on sale!” He Guangwu had learned “Opposing shamans” in the training session in the 1950s, but he too commented wryly, “You can’t tell that story nowadays—that’d be blasphemy!”

Even if the popularity of new stories was highly limited, and the subjects remained traditional, Li Huaiqiang pointed out that the bards’ language had been evolving along with the language of society generally. A certain change of style, reflecting the times, had evidently left him behind.

In the old days you sang of “Lady” or “Mistress” (furen, xiaojie), now it’s “missus” (poyi); in the old days it was “setting up as a family” (chengjia), nowadays it’s “the couple have got together”, “they held hands as they walked”, “they kissed”—it’s so lacking in culture! Old people won’t listen to that stuff, in the old days it was real cultured, now it just ain’t the same. But you have to adapt yer language to the times, eh?

So why should people apparently prefer stories about events many centuries earlier to ones about their society now? Local scholar Meng Haiping explained the ability of the old stories to survive under Maoism:

Traditional stories propound truth, goodness, beauty, and filial piety (zhenshanmeixiao 真善美孝)—that is China’s traditional morality, the Party doesn’t oppose that, and doesn’t suppress it.

Though there is ample evidence to show that they did oppose it, deliberately, regarding it under headings such as “bourgeois morality”, Meng was still making a fair point—because the Party he refers to is that on the ground, where continuity is more evident in local practice than the rupture often advocated by central theory.

Having complained about the coarsening of the bards’ language, Li Huaiqiang went on to lament the changing times:

In the old days bards used to wear a robe, and a hat with a pigtail. Nowadays it’s all simplified. Then it was wagai hats, sitting at a high table; now you don’t get changed, and just sit on a stool, it’s much simpler. And the gods used to be more efficacious, they were dead efficacious—if you didn’t follow them you could die. Once someone’s son died, and the parents made a vow to beg him to come back to life, so I obeyed the gods, and he really did come back to life.

So why didn’t the new stories become popular? Sure, villagers might be conservative and escapist in their tastes, finding stories of emperors and concubines, scholars and maids, generals and outlaws more attractive than propaganda. But the new stories might have been entertaining and meaningful in the contexts of the 1940s too. The irony was that the whole purpose of the new stories since the 1940s was to address current issues of great importance to the peasantry: namely tackling endemic social problems inherited from the old society.

But problems that might be arising under the new society were not now to be publicly aired. I would surmise that villagers might have been open to new stories, but were disillusioned by their glib political correctness, their failure to reflect complex new realities. The new stories were surely rarely heard in the villages apart from at mass meetings by which people were anyway alienated. If villagers were still able to host a performer to sing to invite the gods to heal their livestock, the new stories were inappropriate. In the early period of the 1940s, they might have had considerable novelty, and even helped people confront genuine problems, like forced marriages, opium, landlord exploitation. But maybe the themes didn’t keep pace with the problems: by the 1950s their perceived problems included campaigns, collectivization, irrational directives, and thus the new items seemed false, like the propaganda itself.

Still, as we saw, the stories Han Qixiang performed on his tours in the late 1950s were often semi-improvised according to the events unfolding in the village. That is, problems such as reactionary thinking among the peasants could be ridiculed; perhaps even bourgeois thinking of local leaders; but central policy could hardly be questioned.

As to issues topical since the reforms of the 1980s, several performers mentioned stories about the birth-control policy—that is, supporting it; given its massive unpopularity, has anyone dared sing stories opposing it? If no stories have arisen dedicated to sensitive issues such as official corruption, they are doubtless subtly aired in passing, if not as flagrantly as the fictional balladeer in Mo Yan’s visceral 1988 novel The Garlic Ballads (p.73):

A prefecture head who exterminates clans,

A county administrator who wipes out families;

No lighthearted banter from the mouths of power:

You tell us to plant garlic, and that’s what we do—

So what right have you not to buy our harvest?

Since the government mounts regular poster campaigns warning of sexually transmitted diseases, even if it was slow to admit to the danger of AIDS, I wonder if the bards could now be enlisted to tell stories warning of such perils. It seems unlikely. For a hard-hitting song from blind singer Zhou Yunpeng in Beijing, see here; and for songs on the Coronavirus, click here and here.

At any rate, one can only be impressed by the adaptability and creativity of storytellers, and whatever the constraints on public speaking both under the communes and since the reforms, they must always rely to some extent on keeping their audience entertained with topical remarks which will strike a chord.

Note that it was the texts that the Party cadres sought to reform—the traditional melodic and rhythmic elements were not an object of their attention.

Research and images

By the 1980s, while local scholars did most of the work by contacting the bards through the urban teams, rather than accompanying them on tour, they were now concerned to document ritual aspects of the performance. People’s mind-sets had become much more free than under Maoism—one local scholar who recorded bards for the Anthology was not going to be hoodwinked into toeing the Party line by recording new stories:

When I recorded them, I chose anything about Heaven, Earth and Man, and rejected everything about the Party, Chairman Mao, and Socialism!

One might see this as a political bias in itself, but I would view it as a shrewd correction of any tendency the bards might have to play safe by performing a politically-correct piece for a government representative.

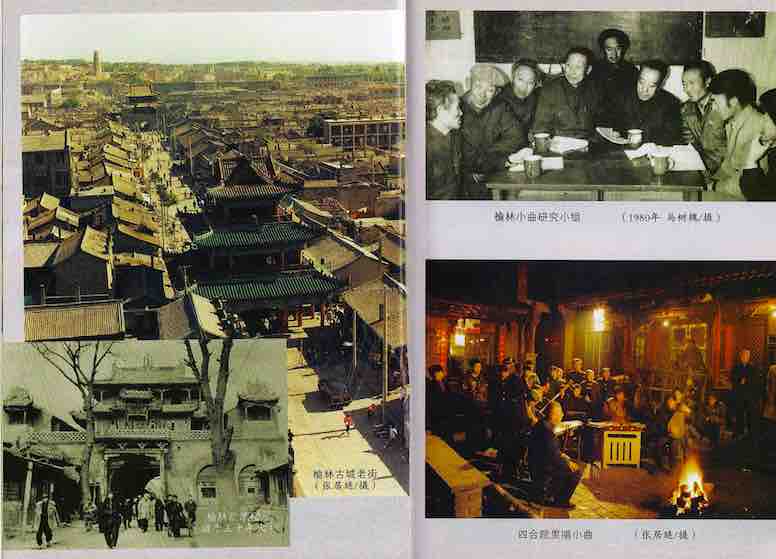

Since Shaanbei is often featured romantically in the national media as a revolutionary base, brief sanitized glimpses of Shaanbei folk culture are occasionally broadcast. The standard images are yangge dancing or a cheesey folk-singer, but in 2001 I saw a young sighted man do a passable imitation of a Shaanbei bard on a national CCTV chat-show featuring the cult Shaanxi novelist Jia Pingwa.

Avant-garde Chinese artists have presented a less revolutionary image of Shaanbei. One fine antidote to Han Qixiang is the blind bard in the novella Life on a string (Ming ruo qinxian) by Shi Tiesheng (b.1951), one of many “educated youth” rusticated to a village near Yan’an in 1969 (see my Shaanbei book, pp.8–11, 76–7). This 1985 story mystically evokes the life of an itinerant blind bard and his young blind disciple:

The old man believes that when he has broken one thousand strings, he can open up his sanxian and find a prescription inside which will restore his sight. When he finally does so, the piece of paper inside is blank.

The story was made into a film by Chen Kaige (1991), director of the brilliant Yellow Earth, also showing the gulf between the harsh realities of rural life and the Party’s ideals.

Such avant-garde creations, with their mystical minimalism, are more popular outside than inside China. While far from ethnography, they at least offer an imaginative alternative to the revolutionary idealism of official sources.

You can find many video clips of Shaanbei bards online (on Chinese sites and even YouTube), most but not all in a commodified style. This one, while close to the traditional setting, is clearly specially staged. In recent years Cao Bozhi 曹伯植 has published prolifically on musical aspects of the genre.

* * *

Now I also learn much from

- Ka-ming Wu, Reinventing Chinese tradition: the cultural politics of late socialism (University of Illinois Press, 2015).

Though Wu immersed herself the lives of her village hosts, she also engaged more with officialdom than I did. She was introduced to bards through the propaganda teams, which look to be more important in her region of the Shaanbei field site than in mine. So whereas bards that I met—even those who had spent periods in the training teams—found the new initiatives evanescent, she tends to take the institutional level as primary, although local variation may also play a part.

For instance, her subheading to Chapter 3 “Propaganda storytelling turned into spiritual service” puts the cart before the horse—when the latter has such a long history, and the former remains only one aspect of their activities. Following blind bard Master Xu around for a month, she gives some excellent vignettes.

She found that

He had transformed his performance into a series of clandestine religious activities and religious performances.

But this was precisely how the blindmen had always earned their living throughout history! A similar slip is

Northern Shaanxi storytelling was originally designed as part of a government-sponsored cultural enrichment mission to poverty-stricken rural areas. (104)

In Chapter 4 Wu valuably describes danwei work-unit performances, which I hadn’t found. She shows bards’ (not always successful) search for performances in such danwei; indeed, even when a bard goes on a solo tour of the countryside she suggests a rather formal arrangement with the village leadership. Conversely, the nearest to this that any bards I met got to was when Li Wenjin announced his arrival in the area to the Black Dragon Temple temple committee—whereupon word soon spread, and household patrons came forward.

Again she shows how bards tend to open with a brief modern propaganda item (no longer based on class politics, as she notes) before launching into a more popular traditional story.

She gives some valuable translations of lyrics, both traditional and modern. Further to my comments above on stories about topical issues, she translates a remarkable item “Quality Control System Spread to Millions” warning against fake consumer goods, performed at a factory; and the 2008 “Alleviate Earthquake Disaster, Look Forward to the Olympics, Increase Productivity” for a staff appreciation event.

While she notes that such national and government messages were overshadowed by the traditional stories that followed them, she reminds us to pay attention to the mutual interpenetration and agenda contestation among the local state, danwei, and folk cultural practitioners.

She finds that storytelling

neither resists nor colludes with the state; nor does it cater to urban tourism or consumption.

And she observes acutely:

Instead of attributing the spiritual revival to a simple return to the storytelling tradition from before the 1940s, I relate it to the huge movement of labor, objects, and emotions between the rural and urban areas.

[…]

My point is not that northern Shaanxi folk storytelling has revived because of depressing rural economic conditions. Rather, I wish to emphasize that the revival of storytelling practice becomes one of the rare social and communal occasions for rural villagers to get together where they can openly discuss all kinds of major rural developmental contradictions: lack of elderly care, split households, and youth who find no career development in remote rural hometowns and who encounter much difficulty surviving in cities.

In short, folk storytelling occasions are valuable not so much because villagers are getting more religious or that the practice is a time-honored heritage. Rather, folk storytelling has become what Megan Moodie called “platforms for articulation”, where local citizens draw traditional cultural resources to discuss pressing concerns of split households among left-behind elderly and young wives in remote communities in a translocal age. (101–102)

Despite these areas for discussion, when she writes so perceptively such variations in focus are welcome.

Conclusion

Despite the substantial material published on Communist reforms of narrative-singing, and ethnomusicologists’ eager search for change and modernization, it was hard while observing daily life in Shaanbei around 2000 to credit the Party’s reform programme with much long- (or even short-) term influence.

As Guo Yuhua observes, people remained loyal to their traditional concept of local village culture rather than to the state. Though state-funded troupes are undoubtedly an aspect of overall activity, this point appears to be of wide relevance for ritual activity and expressive culture in the Chinese countryside today, and for our understanding of modern China.

If the bards are now threatened by the recent spread of TV and pop music, they are still in demand for their “stories for well-being” as well as for their healing skills. While they do assemble for public rituals like temple fairs and New Year, they mostly perform solo. From the 1940s, a disjuncture emerged between the secular political performances of the official teams and the rituals of the solo bards. Narrative-singing has perhaps become a lesser aspect of the blindmen’s activities than their godfather and healing duties. Indeed, since sighted bards do not necessarily learn the healing arts of blind men, a potential divorce also looms between narrative-singing and healing—all the more since people can now learn stories by listening to commercial tapes.

My point is not to belittle official efforts, either in the cultural or political spheres. But we should avoid basing our assessments either on the new stories of Han Qixiang or on a simple revival or reinvention since around 1980. As Ju Xi comments, criticizing the recent interpretations of “secularization” (compared with imperial China) and “revival” (compared with the Maoist era), both of which portray Chinese religion as somewhat isolated from society, local religion is not merely a “spiritual creation” or “cultural heritage”—it’s a cultural resource and social power which can play active roles in contemporary rural society.

The Party never managed to “eliminate superstition”, but complex social and economic changes continued to affect ritual life and expressive culture both under Maoism and since the reforms. Studying their changing fortunes in such a society requires a nuanced approach.

Click here for a trailer for the documentary Shujiang (Cao Jianbiao 曹建标, 2019). See also Bards of Henan, and my roundup of posts on narrative-singing.

.

[1] This article is based on Part Two of my book Ritual and music of north China, volume 2: Shaanbei, (where you can find further refs. and characters)—note §C of the accompanying DVD. See also my “Turning a blind ear: bards of Shaanbei”, CHINOPERL 27 (2007); and Zhang Zhentao, Shengman shanmen 声漫山门, pp.353–79. I use the term “bard” for convenience, and to hint at their broader ritual duties.

In March 1965, seeing no way out, he took the No.15 bus to enter “the gates of hell”, becoming a “resettled worker” at the No.2 Brickyard in Xi’an. His romantic illusions about finding Robin Hood types were soon dispelled. Though they were allowed to take occasional breaks in town, it was effectively a labour camp.

In March 1965, seeing no way out, he took the No.15 bus to enter “the gates of hell”, becoming a “resettled worker” at the No.2 Brickyard in Xi’an. His romantic illusions about finding Robin Hood types were soon dispelled. Though they were allowed to take occasional breaks in town, it was effectively a labour camp. I don’t think that Grandfather was aware of the extent to which the temples had been politicised or to which the Party’s promise of religious freedom was pretence. There was a reason why he had been granted prestigious positions in the Buddhist Association and the Municipal Political Consultative Committee, along with a monthly subsidy of 100 yuan. As a prominent Buddhist spokesman for official policies he has an unwitting figurehead for the Party’s United Front policy of the political assimilation of non-party members. In the comparatively relaxed climate of the past few years he had fallen for a host of false promises. Imagining that he could promote Buddhism as he had before the Communists, he had continued to advocate religious reform. Unfortunately his proposals—to hold gatherings to celebrate Buddhism, for example, and to require temples to enforce religious discipline—had aroused the ire of both the Party and the monastic community. Maybe even at the bitter end he still failed to understand that his religious zeal exceeded the limits tolerated by the authorities, who saw the latest political campaign as an opportunity to attack him.

I don’t think that Grandfather was aware of the extent to which the temples had been politicised or to which the Party’s promise of religious freedom was pretence. There was a reason why he had been granted prestigious positions in the Buddhist Association and the Municipal Political Consultative Committee, along with a monthly subsidy of 100 yuan. As a prominent Buddhist spokesman for official policies he has an unwitting figurehead for the Party’s United Front policy of the political assimilation of non-party members. In the comparatively relaxed climate of the past few years he had fallen for a host of false promises. Imagining that he could promote Buddhism as he had before the Communists, he had continued to advocate religious reform. Unfortunately his proposals—to hold gatherings to celebrate Buddhism, for example, and to require temples to enforce religious discipline—had aroused the ire of both the Party and the monastic community. Maybe even at the bitter end he still failed to understand that his religious zeal exceeded the limits tolerated by the authorities, who saw the latest political campaign as an opportunity to attack him.

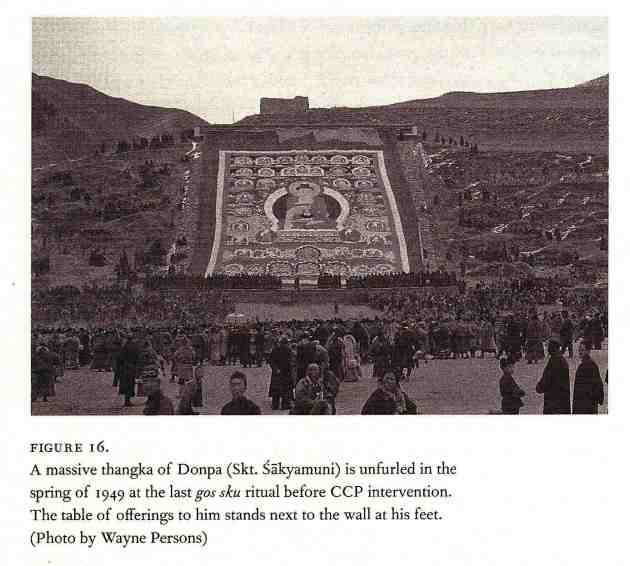

She unpacks the multiple meanings of the cham dance ritual, “the culminating component of the greater mandalising event that was the annual Great Prayer Festival at the lunar New Year”. Following the destabilizing of the frontier zone in the wake of the decline of the Qing rule and the splintering of rule in China, in 1949 the monastery held the last cham before the Chinese occupation.

She unpacks the multiple meanings of the cham dance ritual, “the culminating component of the greater mandalising event that was the annual Great Prayer Festival at the lunar New Year”. Following the destabilizing of the frontier zone in the wake of the decline of the Qing rule and the splintering of rule in China, in 1949 the monastery held the last cham before the Chinese occupation.

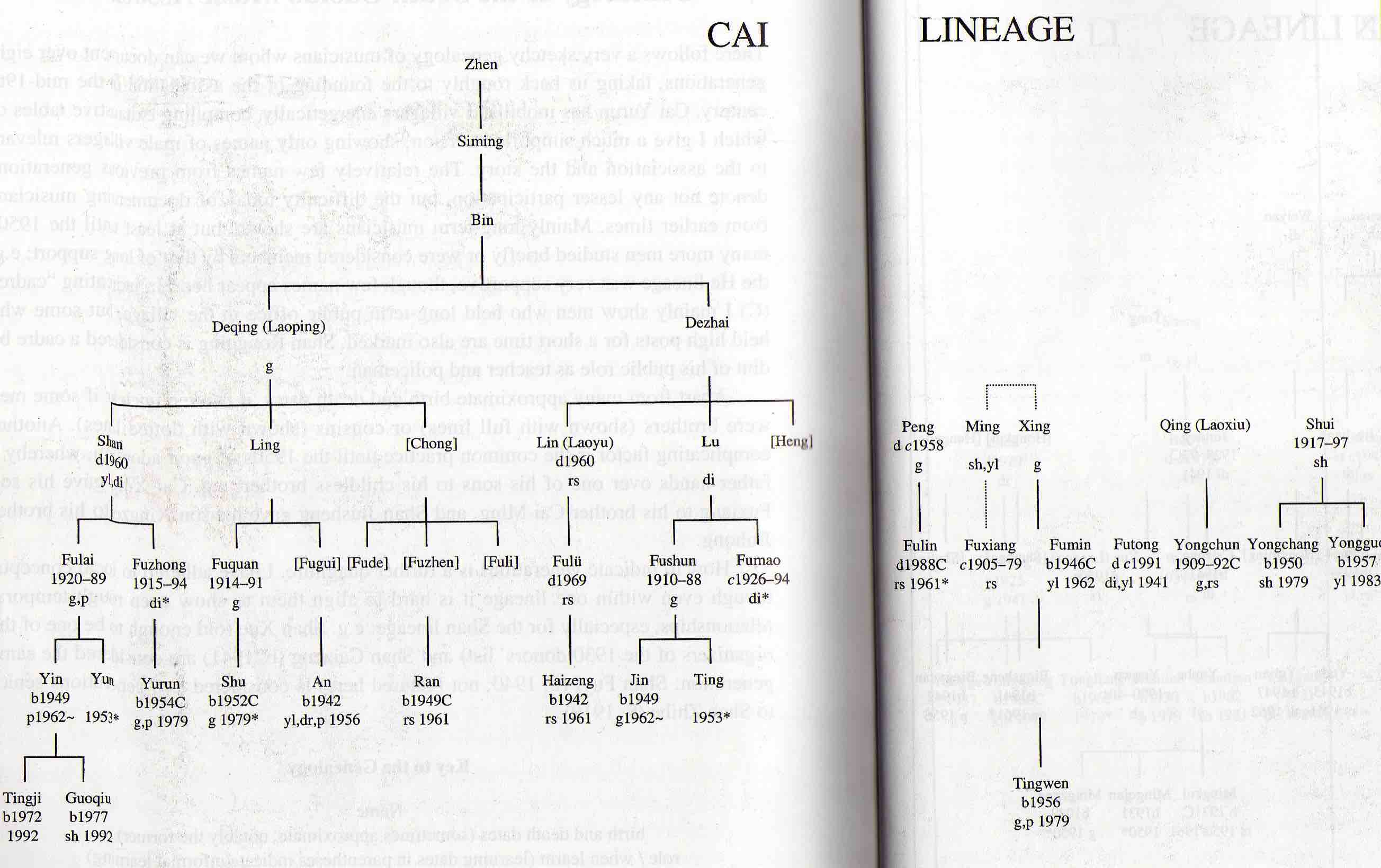

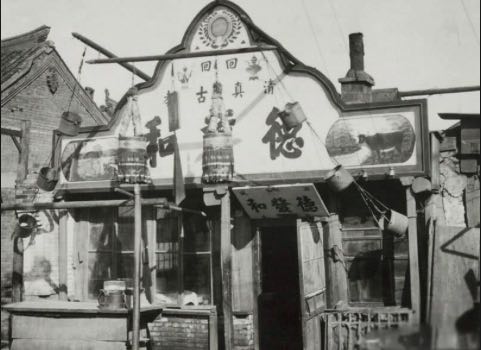

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu. But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the

But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the

Laurence too was immediately captivated by the sound of the qin:

Laurence too was immediately captivated by the sound of the qin:

As we read up further, we now speculate that since Kangxi saw the poem on a visit to Wutaishan, and as Buddhist ritual manuals do contain poems, it could have got into one such manual there; spreading further north, it might thence have got into Daoist manuals too—which, after all, contain plenty of Buddhist elements (my book, e.g. p.226).

As we read up further, we now speculate that since Kangxi saw the poem on a visit to Wutaishan, and as Buddhist ritual manuals do contain poems, it could have got into one such manual there; spreading further north, it might thence have got into Daoist manuals too—which, after all, contain plenty of Buddhist elements (my book, e.g. p.226).

So Li Manshan gets to record me singing a piece I barely know, but I never get to record him. Anyway he always sets off from a really low pitch, so the result tends to sound a bit like Tibetan chanting. When the band sings a cappella hymns for funerals,

So Li Manshan gets to record me singing a piece I barely know, but I never get to record him. Anyway he always sets off from a really low pitch, so the result tends to sound a bit like Tibetan chanting. When the band sings a cappella hymns for funerals,