Ethnomusicology at home

Following the recent loss of the great Bruno Nettl, I’ve been revisiting another of his stimulating books,

- Heartland excursions: ethnomusicological reflections on schools of music (1995).

It’s thanks to works like this that we can now understand WAM within the context of musicking in societies throughout the world. Such “ethnography at home” belongs with a corpus of studies like those of Ruth Finnegan, Christopher Small, Henry Kingsbury, and more recently Stephen Cottrell.

Nettl opens his Introduction thus:

Let me be quite personal. What is it about ethnomusicology that has fascinated me for over some four decades? At first, it was the opportunity of looking at something quite strange, of hearing totally unexpected musical sounds and experiencing thoroughly unfamiliar ideas about music. Later, to learn to look at any of the world’s cultures, and listen to any of the musics, without being judgmental. And further on, the notion that one should find ways of comprehending an entire musical culture, identifying its central paradigms, and finding points of entry, or perhaps handles, for grasping a culture or capturing a music. And eventually, having also practiced the outsider’s view, to look also at the familiar as if it were not, at one’s own culture as if one were a foreigner to it.

He shows that while this idea was taking root in ethnomusicology by the 1980s, scholars native to the traditions they researched (Africans, Indians, Native Americans, Indonesians, and so on—and Chinese, of course) had been studying the musics of their own “cultural backyards” all along; as indeed had those studying urban minority cultures in North America and Europe, including popular genres.

Listing some major contributors to the field, Nettl explains his description of WAM as “the last bastion of unstudied musical culture”: ethnomusicologists

try to understand the musical culture through a microcosm, to provide an even-handed approach without judgment, to look as well as possible at the familiar as if one were an outsider, to see the world of music as a component of culture in the anthropological sense of that word, and to view their own music from a world perspective.

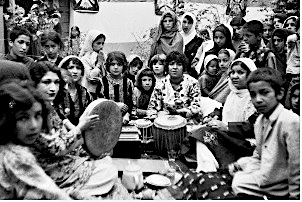

Here his main subject is his own musical “home”: schools of music in universities in the Midwest (rather than the world of professional WAM performance, for which see Small, Cottrell, and so on). He makes suggestive comparisons with other musical cultures, notably those of the Blackfoot, Tehran, and Madras.

Always seeking to elicit structures, he comments

A wonderful musical system may not mean a wonderful cultural system, only the desire for one; a musical system with sharp social distinctions may reflect a social system, or it may only remind us that the social system contains the seeds of inequality.

He ends the Introduction by explaining that his purpose is not (quite?) to criticise—reminding me of Small’s ambivalence and the doubts of his reviewers:

Although I may discuss Western classical music—and the subculture that practices and teaches it in one of its 20th-century venues—with a raised forefinger, or with tongue in cheek, or with wrinkled nose, and maybe even with a note of cynicism or sarcasm, and although I think it may reflect the cultural structure of a sometimes mean and unkind society, I nevertheless cannot imagine life without it.

The Royal College of Music, London.

The Royal College of Music, London.

In Chapter 1 Nettl views the music school as “something like a religious system or a social system in which both the living and the dead participate” (cf. Aboriginal culture), viewing it as “a society ruled by deities with sacred texts, rituals, ceremonial numbers, and a priesthood”. He introduces the extraterrestrial ethnomusicologist from Mars, who

arrives at the mid-western school of music and begins work by listening to conversations, reading concert programs, and eavesdropping at rehearsals, lessons, and performances. The E.T. is overwhelmed by hearing a huge number of names of persons, but eventually it realizes that many of these persons are alive, but many are no longer living and yet the rhetoric treats them similarly. […]

The E.T. soon finds that many kinds of figures populate the school: students, teachers, administrators, members of audiences, musicians who are not present but are known, and a large number of musicians who are not living but are treated as friends in conversation. Among these are a few who seem to be dominant figures in the school. They constitute pantheon, the composers about whom one rarely if ever hears a critical word. Two seem to get more (well, just a tiny bit more) attention than the rest: their names are Mozart and Beethoven, and they appear to have the roles of chief deities.

He discusses

the Mozart and Beethoven of the present, as they are perceived by music lovers today, as living figures in today’s musical culture. My purpose is not, however, to participate in the now widely respected study of reception history, but to characterize contemporary art music culture.

Going on to describe pantheons and canons. By way of the dream songs of the Blackfoot, Nettl discusses acts of creation, and the identity of the quasi-sacred composer. The “great works” of the WAM canon are akin to religious scriptures, served by a priesthood of performers and musicologists.

The Concertgebouw, Amsterdam; right, Mahler.

He discusses the significance of the names of the great composers engraved on concert halls and music schools, making the analogy with bumper stickers and T-shirts. What is the purpose here? Such buildings are like shrines where we should pay homage.

Despite the apparent claim to eternity, tastes change: as with other league tables, composers can be promoted or demoted over time. This can be entertaining; to Nettl’s instances from the USA, we might add the list of names at the Concertgebouw, where

around the balcony and ceiling of each are inscribed the names of the great composers, perceived from an earlier Dutch perspective: Wagenaar beside Tchaikovsky, Dopper next to Debussy, and Rontgen alongside Richard Strauss, while in the small hall Rubinstein and Hiller rub shoulders with Mozart and Beethoven.

Suggesting that the Mozart–Beethoven axis reflects the dualism of modern Western thought (genius and labour, light and heavy, Zeus and Prometheus), he notes that as in other pantheons, lesser deities have their distinct personalities too.

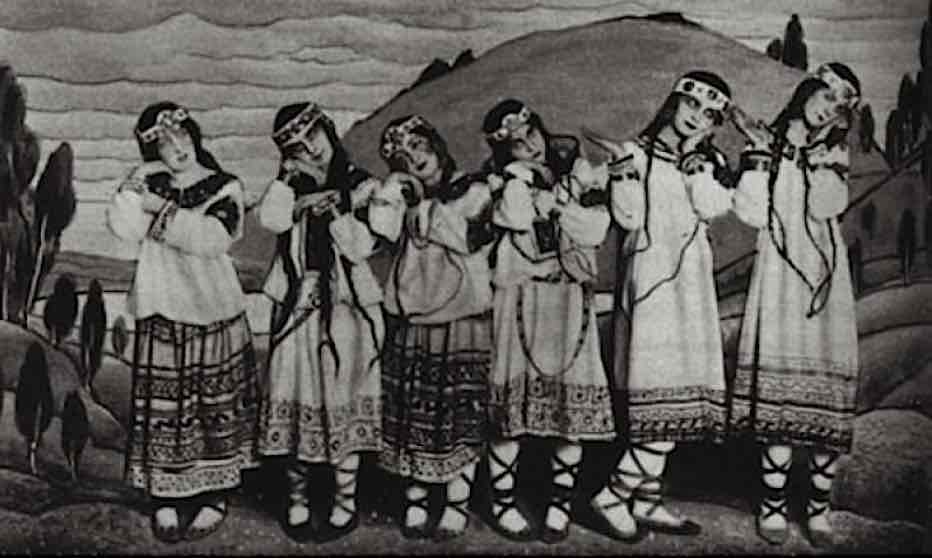

As in The study of ethnomusicology, Nettl explores the nature and role of genius. He discusses myths central to cultures, from the supernatural beaver of the Blackfoot to those of Mozart and Beethoven. He explores the notion of greatness—large orchestral performances of great works by great composers; and costume (“tuxedos, blazers, turtlenecks, robes, dhotis, Elizabethan garb, T-shirts with holes, leather jackets”) as an indicator of musical hierarchies:

Uniform accomplishes the depersonalization of the individual, giving the orchestra a faceless quality that is exacerbated by requirements of such uniform behaviour as bowing. […] Your uniform tells people what you do, and musical uniforms tell what kind of music musicians “do”.

He is alert to gender:

It is indicative of gender roles in American society that these uniforms derive principally from men’s dress, that there is less difference among their various female versions, and that women sometimes simply use the men’s versions of uniforms.

and always takes a broad view:

The tendency of musicians in Western culture to wear clothes different from their everyday attire contrasts with the custom of Plains Indian powwow singers, who wear precisely and determinedly what they might wear at other times—jeans, T-shirts, and farmers’ caps—despite the clearly special nature of musical performance. Perhaps they do so because virtually all others present—the dancers—are in costume, and the singers wish to separate themselves from them.

The symphony orchestra may be seen as a metaphor of industrial factory, political organisation, and colonial empire. The concert master is “a kind of factory foreman keeping things in shape for the management”, while the conductor, with a “baton” of military origin, is the general:

he gets credits for victories, is listed on the album cover, takes bows, but is not heard and so risks little. […] The occupants of the first chairs are officers who have a certain amount of authority over their troops, whose main task is to march—that is, bow and finger—in unison, mainly for the appearance of discipline. There is little democratic discussion. […] Conductors are often permitted or even expected to be eccentric; sport long hair, strange dress, and a foreign accent; and lead a strange life.

He enjoys reiterating the metaphor:

If the orchestra is a kind of factory or plantation for producing great music or an army for exhibiting perfection on the parade ground, it is principally in the service of the great masters.

Nettl unpacks the major role of notation in the culture, and the strange notion of “reading” music:

Having perhaps forgotten that they learned their first songs by hearing them, many of the denizens cannot conceive of a musical culture that does not use notation, and until recently my colleagues were inclined to marvel at my account of Indian musicians’ improvising interestingly for an hour, or Blackfoot Indians’ maintaining a repertory of hundreds of songs, keeping them separate and knowing which go where in rituals, without any visual mnemonics.

Notation is a meta-language:

Various musicians can communicate with each other and play in the same orchestra, even when they do not share a language. It is also a separating device in the sense that it enables individual musicians in orchestras or bands to play their parts without knowing what sounds will emerge or how the entire work sounds.

He wonders what it is that is transmitted:

We should ascertain whether a performer is required to play a piece exactly as he or she learns it, whether changes are permitted, whether there are interpretive choices, or even whether there is the requirement that a piece be altered every time it is rendered. The cultures of the world vary greatly in their answers to these questions.

He discusses the changing structures of concert programming, again comparing other cultures:

In a concert of the classical music of South India, the multi-sectioned improvised number called ragam-tanam-pallavi begins just after the midpoint, although there is actually no intermission. In Persian classical music, the conceptually central and most prestigious section, the improvised Āvāz, appears in the very centre of the full-blown performance.

He ends the chapter provocatively:

In this system of Western culture that produces wonderful music, what are the principles and values that are expressed and that underlie it? Here are intriguing concepts such as genius, discipline, efficiency, the hierarchical pyramid of musics and composers, the musician as stranger and outsider, the wonders of complexity, the stimulus of innovation, and music as a great thing with metaphorical extensions. But we are also forced to suggest dictatorship, conformity, a rigid class structure, overspecialization, and a love of mere bigness are all explicitly or by implication extolled. One may counter that the analysis is faulty, that instead of conformity there is cooperation, instead of authoritarians there are leaders. Or argue that the kind of social structure described, for all its undesirable aspects, is essential for the proper performance of music by the great masters, that in order for music of such an incredibly elite character as that of Mozart’s or Beethoven’s to be created and performed one must simply sacrifice independence and personal opinion, must undertake an incredible amount of discipline and accept dictates of an elite wherever they lead.

But Nettl never downplays the role of hierarchies in other traditions. He opens Chapter 2 by observing the competitive, even conflicting distinctions among performers in south Indian music, where caste, professional status, and gender play major roles. He then explores the opposing forces of our schools of music (teachers, students, administrators; performers and academics; singers, string players, wind players; conductors and conducted), reflecting the hierarchies, the “corporate ladders”, in American society. As ever he offers parallels: the progression by age of singing and playing didjeridu in Aboriginal societies, Persian radif, and south India again. He elaborates on the industrial model, with its customers (students and audiences) and products; and he discusses classes of musicianship, and competing central and peripheral roles. On the tension between music educationists and musicologists, he observes:

Performers see musicologists as a kind of police, imposing music history requirements on their students, making them take entrance examinations, and otherwise forcing them to jump through hoops of (they think) an essentially irrelevant defence of an obscure and ephemeral canon. They may see little need for their students to know about medieval and Renaissance music, or about the music of India and China.

Still more revealing is the division between singers and instrumentalists. Again he highlights gender, noting that in other societies (and indeed in our own popular music and jazz) women sing more commonly than playing instruments. Of course, in line with broader social changes over recent decades, women have come to play an increasing role in orchestras and as conductors. Nettl unpacks cultural stereotypes:

Men are traditionally thought in this society to be better at handling tools (e.g., instruments) and better at solving intellectual problems, whereas women are “closer to nature” and more “emotional”.

Such distinctions are to some extent submerged beneath the wider struggles between the music school and the rest of the university, the arts versus the sciences, and art music versus pop and rock.

He observes a further distinction between “bowing and blowing”, with string players generally more esteemed than wind players, mainly due to their greater place in the canon. And he notes the major role of the piano.

The maintenance of the stock of pianos is one of the major financial—and ideological—commitments of the school.

By way of a discussion of the importance of heritage (like Indian gharanas), adducing pedagogical lineages such as those of Theodor Leschetisky, Leopold Auer, and Ivan Galamian, he moves onto the various types of ensembles within the school. The role of the conductor (another godlike persona, further elevated in the professional world) is discussed at greater length in Small’s Musicking.and Norman Lebrecht, The maestro myth.

If the music school might seem a potential meeting-place for all musics, in Chapter 3 Nettl’s ethnomusicologist from Mars quickly notes that not even the various genres of WAM are treated on equal terms, and when other types of music are considered at all, it is only on special terms; indeed, in some ways

The music school functions almost as an institution for the suppression of certain musics.

This is worth noting, though it’s no great surprise: other musical institutions around the world (families in Rajasthan or Andalucia, and so on) also naturally privilege their own traditions; outside music too, other Western institutions have long been selective about including popular genres. Nettl likens such policing of choices to “purification rituals”. He suggests the model of concentric circles to evoke the taxonomy and relative value of musics at the school, with the canon at its centre; as in the world’s cultures at large, genres converge and collide. Again, he outlines the changing modern history of the school of music, with early and contemporary musics gaining a certain ground, as well as jazz, folk, and world music, noting degrees of bimusicality and polymusicality, as is routine outside the elite institution.

A Blackfoot man whom I knew claimed to have two musics central to his life—the intertribal powwow repertory of Plains Indian culture and the country and western music that he plays in a small band in a bar. He was also trying to learn, but slowly, some older and explicitly Blackfoot ceremonial music. He played trumpet in high school band and learned the typical repertory of such institutions (marches and some concert band music), he goes to a Methodist church and can sing several hymns from memory, and—a person of some curiosity—he has seen two opera or musical comedy productions at a nearby college.

Many institutions, however (his list includes the Met, the First Lutheran Church, groups in Tehran and Madras, and some radio stations), are mainly unimusical.

In North American society he finds a certain potential mediation between styles in the form of concerts, record stores, the film industry, and even the music school. He unpacks the various kinds of music presented in concert—quite diverse, yet still only rarely encompassing rock and Country.

The similarity of the concentric circle structure to a colonial system is suggestive. Musics outside the central repertory may enter the hallowed space by way of a servants’ entrance: classes in musicology. They may be accepted (performed) as long as they behave like the central repertory (performed in concerts with traditional structure) but remain separate (no sitar or electronic music in an orchestral and quartet concert). It is difficult to avoid a comparison with the colonialist who expects the colonized native to behave like himself (take up Christianity and give up having two wives) but at the same time to keep his distance (avoid intermarrying with the colonialist population).

He reminds us that each society has its own music history:

Nowhere is music simply “what happened”; it is always interpreted in ways that are determined by, and support, fundamental values and principles of culture. Even where societies have little information about their own musical past, they still have ideas and beliefs of what happened based on myth, folklore, and oral tradition; they also have some idea of how music history “works”, about its mechanisms of change and continuity.

While many cultures emphasize that their music is ancient, a pure expression of the culture, distinct from—and even superior to—the music of other societies, this notion is particularly central to WAM. Nettl ponders the “specialness” of Western music history (cf. Is Western Art Music superior?).

Other societies also insist on the uniqueness of their own music, but they usually do not suggest that it ought to be adopted by all other cultures. Western musicians, like the Western politicians of yore, impose their music on the rest of the world. Western society regards its [art?—SJ] culture as different from the rest, not only in degree but also in kind, and reflects this in its attitude towards music.

Nettl notes the contrasting stresses in WAM between the values of the old and the demand for innovation. In the potential meeting of musics he finds convergences and collisions, encouraged or inhibited by the preservation of purity, specialised audiences, and among the “peripheral” ensembles, the privileging of those that seem to reflect the values of the central canon.

He broaches the widely-used metaphors of the melting-pot and mosaic (and the bazaar is another one). Within the central repertoire the meeting of musics is blunted, while genres outside it—which are often unsuitable to concerts, for a start—are approximated to its ethos: the (modern) concert format rules. Mediation is limited: the peripheral genres are “permitted to maintain a modest spot in the institution if they bow to the values of the centre”. Again, all this may seem unremarkable, a common feature of musical groups around the world.

In Chapter 4, mustering his usual cross-cultural comparisons, Nettl further explores the school’s repertoire, with its central canon. But he begins with more Martian contextualising, considering the obligatory songs of the music school and the wider society, “that everybody seems to know and can sing, a group that she may not find attractive but seems to hear a lot”: the ceremonial repertoire, such as songs for life-cycle and calendrical events and graduation ceremonies, including Happy Birthday, Auld lang syne, and Stars and stripes forever. Such songs might also seem to be “central”, yet “it is not what the denizens of the Music Building regard as their culture’s great music, and most of it is not serious music to them”; despite the ritual origins of much of the core repertoire,

in the art music world of today, it seems inappropriate to associate what we consider the best music with specific ritual or ceremonial functions; it is a way of denigrating the music’s stature.

Typically, he compares such pieces to ritual items like Peyote songs or the Proper and Ordinary of the Christian Mass. The rituals of the Music Building

are not carried out, in the last analysis, for the sake of humans and their necessary activities, but in the service of the great masters, whose works stand above the hustle and bustle of human coming and going and exist as art for art’s sake.

He now points out that rather than defining the “central” as “normal” or indeed “popular”, in the world of WAM it resides in the more abstruse “great works” of the canon, which he proceeds to unpack. Musical “greatness” seem to reside in bigness and complexity, and its centre lies between 1720 and 1920.

Do the typical musical structures of that time reflect the social structure that the American middle-class desires, or was it what society used to desire, or did musical structure and the relationship of musical and social organisation just freeze at some point, as Small has suggested?

Nettl surmises that

the kinds of relationships that are evident in the the society of people in the Music Building, and in art music generally, play an important role in determining ways in which they conceive of the musical materials themselves—pieces of music, kinds of compositions, and instruments.

Cellist, Shanghai Conservatoire, 1986. My photo.

Cellist, Shanghai Conservatoire, 1986. My photo.

Noting that the taxonomy of instruments among cultures is modeled on important aspects of their worldviews, adducing Chinese and Arabic classifications, he considers “families” of instruments—a concept also adopted in African societies. He adduces the development of orchestras with SATB “choirs” of “traditional” instruments as a pervasive pattern of musical Westernization:

The four-part structure does reflect some major tensions in family and between genders and generations in society—and this perhaps accounts for its amazing tenacity.

He discusses the hierarchical concept of leaders and followers (accompanists) in music and society (cf. McClary on Brandenburg 5), going on to consider genres and forms within the “ruling class” of WAM.

Is it not conceivable that certain composers and groups of composers or musical cultures simply discovered better ways of producing music, and that this ability was recognized by later musicians and listeners?

Yet

We are tempted to ask whether modern music listeners are most comfortable with music reflecting a social structure that precedes the social upheavals of the French revolution and the 19th and early 20th centuries.

While noting that some of the canonical works, like Mozart operas, “go further than simply representing or going along with the inequalities and inequities of society”: they also provide a critique of the system. Nettl is

struck by the ways in which the critique is incorporated into a style that otherwise reflects a conservative view of society.

He explores the values of the concerto, with its “tension between art as the organization of forces and art as individual accomplishment”.

Under “the priesthood of the repertory” and the concept of equality he notes some of the most highly valued music, such as fugues,

in which there is textual equality of parts, and in which distinctions of power, volume, tone colour, and role specialization are relatively unimportant, a body of music that has, in addition to its sonic existence, a life in the abstract. This is music whose structural details play a greater role than the pleasurable nature of its sound, moment to moment. In general, it has no programmatic content and perhaps little in the way of obvious emotional connotations.

The discipline of the fugue “seems to result from a combination of technical and social principles”, and it had a significant afterlife even after the heyday of the art.

He reflects on the role of the string quartet in the canon—I’d love to see him or Susan McClary discussing the Große Fuge, so very full of conflict. And he surveys the quartet audience (“broken down by age and sex”, like Keith Richards).

Discussing “cultural performance”, Nettl again opens with the instructive instance of the Blackfoot powwow, going on to consider the tensions of the secular academic “commencement” ceremony, where the values and allegiances of the WAM community are celebrated and graduates admitted to the priesthood of elite music, an army to defend its beleaguered position in society. He offers an interlude on the colour pink, suggestive of subordination, curiously used for their academic hoods since 1895.

In his brief Afterword, Nettl, like Small, expands on the trepidation he expressed at surveying his heartland in such terms. In an important passage he considers the related work of Henry Kingsbury, Music, talent and performance: a conservatory system (1988), and its review by Ellen Koskoff (Ethnomusicology 34.2, 1990)—herself no hidebound defender of the autonomy of WAM, but a great ethnomusicologist focused on gender issues (see Flamenco 2, under “Gender”):

The impression Kingsbury gives to some readers is of a culture or subculture that is essentially mean and even brutish to most of its population. Ellen Koskoff’s review suggests that Kingsbury has “an axe to grind”; that he wishes to “laugh, poke fun at, or cry… at the grim reality of conservatory life” [cf. Mozart in the jungle]; and that he will only convince those musicians “who remember their own musical training with resentment and who want, deep down, to settle the score”. Kingsbury does not totally deny these aims in his response, because he closes his rejoinder by citing Howard Becker to the effect that social scientists must make judgments, and that “appeals for ‘balanced’ accounts in the social sciences are all too often merely veiled admonitions to endorse the status quo”. Kingsbury would presumably like to see change in the conservatory, change that would improve life and maybe improve music, and I applaud and agree. Even the rosiest picture would have to contain its share of grimness. And so I, too, would like to see change, although at this point I am not sure from what to what.

It’s a complicated place, the Heartland music school, existing as it does at a number of crossroads. It’s a place that aims specifically to teach a set of values, and it does so not only through practical instruction but also through the presentation of a quasi-religious system. It’s a place that puts “music” first and looks at music as if it were a reflection of a homogeneous human society. It is an umbrella under which different approaches to music can coexist, interact, and argue. It collects many kinds of music, brought from many places and composed at many different times, putting them all under one roof but making them all march to the drummer of the central classical tradition. It reflects the culture in which it lives, but it also tries to direct that culture in certain directions. […]

However, I have tried to avoid endorsing anything. If an explicitly critical stance will preach only to the converted, then perhaps an approach that tries to present a balanced picture might show champions of the status quo why they should depart from it. But that will have to be their own choice. An article of faith with most ethnomusicologists is that they should try their best to avoid disturbing the cultures they study or introducing new musics and practices, and that they should also restrain themselves from unduly encouraging musical cultures to eschew change in order to preserve the past. And, in my role of ethnomusicologist, I wish to abide by this principle, even when considering the culture in which I live. As much as I can.

Yet again I relish the lucid accessibility of Nettl’s style. As a system within a particular society, the rules of WAM deserve unpacking just like those of any other. But, just as Nettl implies, while WAM scholars and aficionados would benefit greatly from such an analysis, I suspect they may be the last to read studies like this; still, they should feel stimulated rather than threatened by this kind of approach.

For more armchair ethnography from my Chiswick home, see here. Note also The hidden musicians.

Posts on this blog inspired by his insights include:

Posts on this blog inspired by his insights include:

While I played

While I played