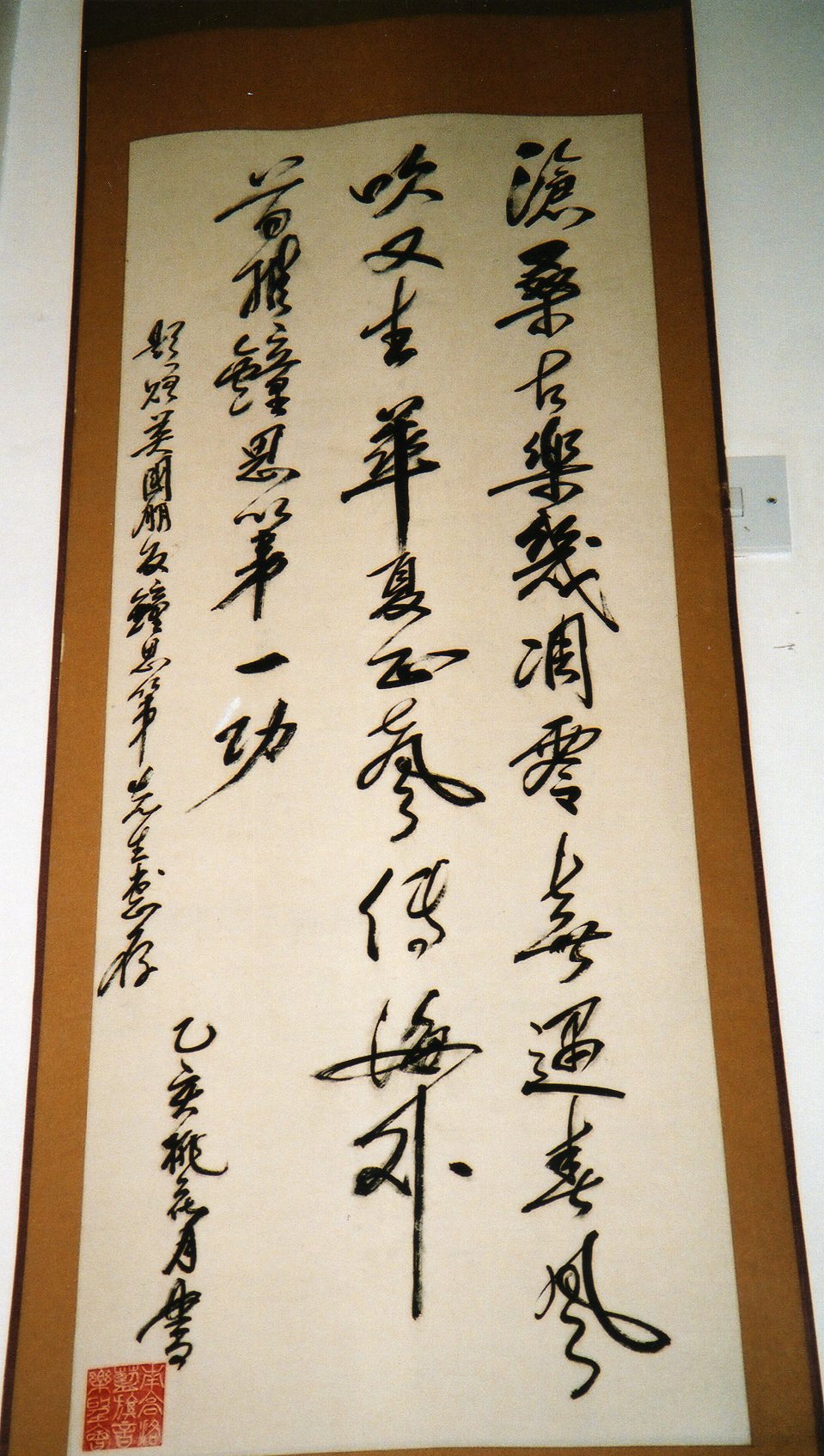

Liuru, 2003.

*Part of a series on blind musicians in China and elsewhere!*

To follow my post on the secret language of blind shawm players in north Shanxi, here I’d like to expand my article on shawm bands in China to introduce further some of those from whom I learned in Yanggao county—based on my book

- Music and ritual of north China: shawm bands in Shanxi (2007)

(which, need I add, is available in paperback, with its fine DVD complementing my film on Li Manshan! See also here).

As you read this, do also listen to the amazingly complex, visceral suites that the Yanggao shawm bands (here known as gujiang 鼓匠) performed for folk ceremonial through turbulent times right until the 21st century (Dissolving boundaries, and ##5 and 11 of the Playlist in the sidebar, with commentary here).

* * *

As throughout the world, blind musicians in China have been much praised, from the ancient Master Kuang to the Daoist beggar Abing; but their real lives are far from such hagiography. By contrast with Shaanbei, or indeed further south in Shanxi, (see n.2 here), where blind boys might find a livelihood either through solo narrative-singing or by taking part in shawm bands (again, for Shaanbei, see here, under “Expressive culture”), in north Shanxi the latter made a more common career path.

The gujiang bands of Yanggao county commonly included blind players. By 1958 Yanggao town had three bands, one led by blindman Song Chengxin (c1921–76), a disciple of Chen Gang in Anjiaxiang lane. But town players were reluctant to accept disciples from outside their own family, and two of the blind players we met sought their apprenticeship in nearby Xiejiatun village.

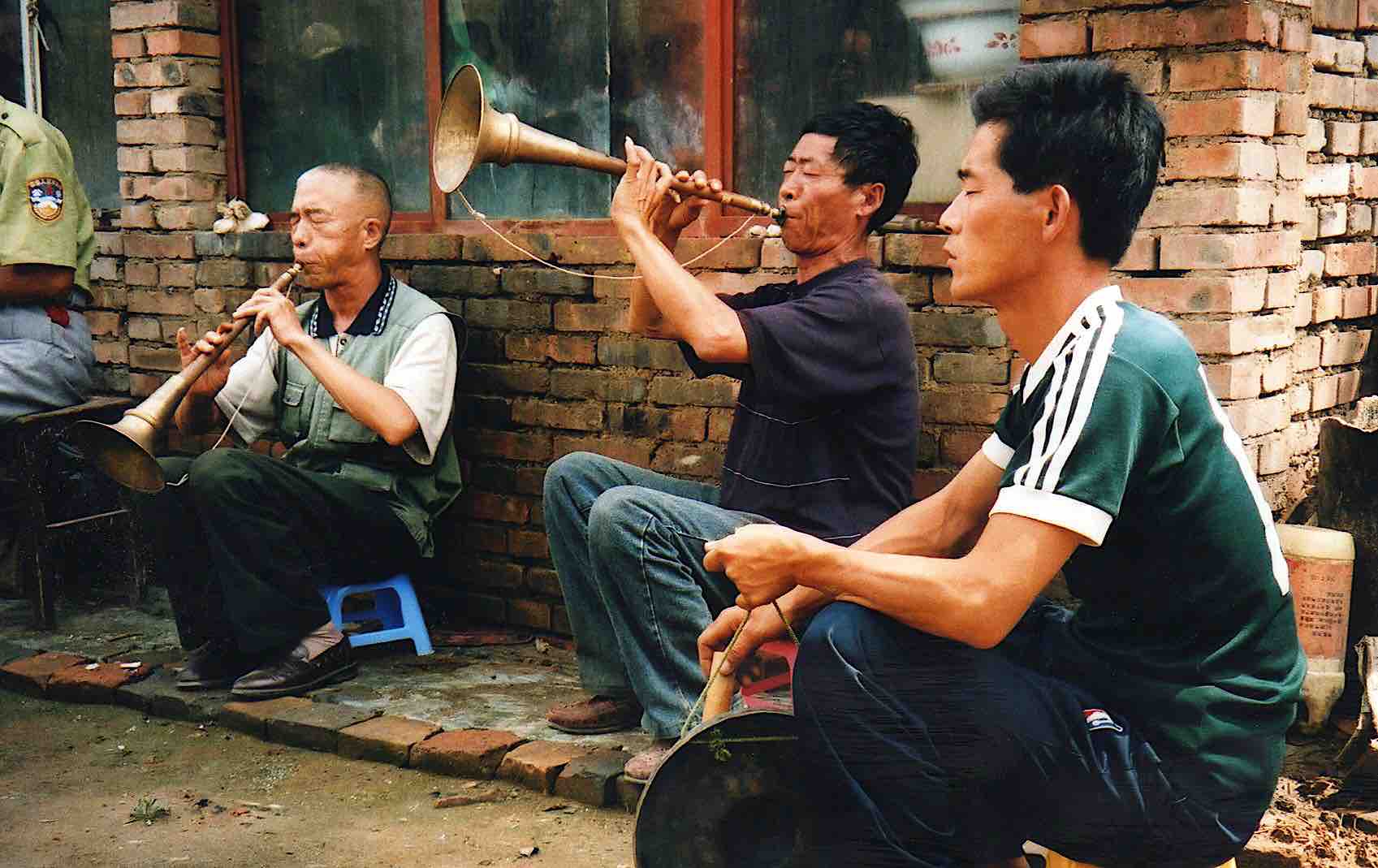

Blind shawm players, Greater Antan village funeral 1991.

I found blind shawm players among a group at a village funeral in 1991, and there were still three distinguished blind gujiang in Yanggao town in 2003. But by then, along with slight but significant improvements in healthcare, there were now fewer younger blind men and thus fewer blind gujiang. Although the senior Erhur and Yin San still managed to lead bands by dint of their seniority and support network, other blind gujiang were less able to keep up with the times, and it was becoming a less likely profession for blind boys.

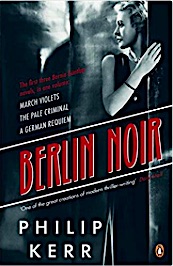

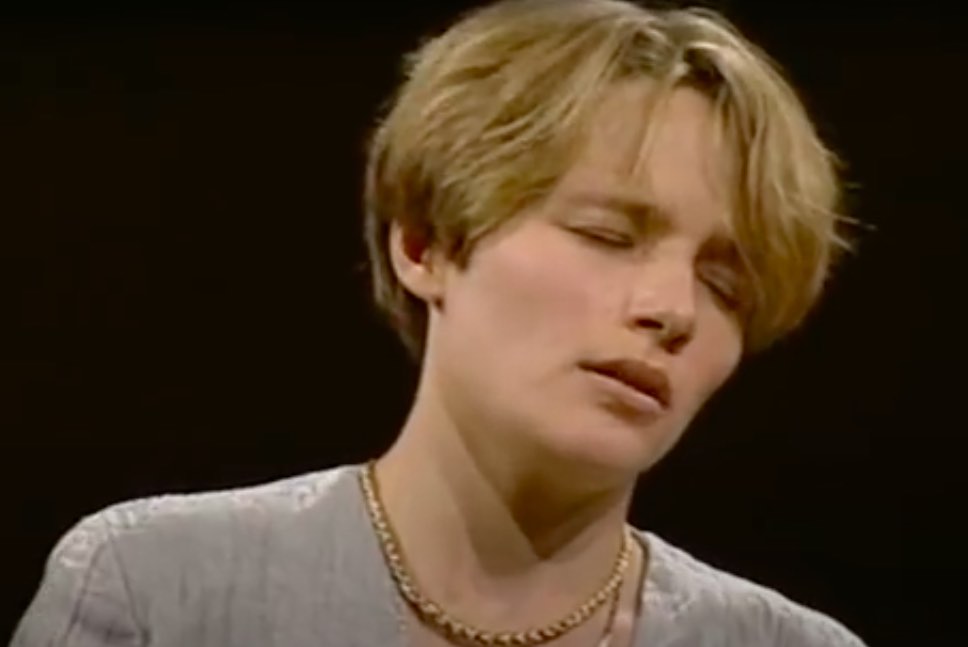

Liuru

By 2003, the most senior gujiang in the county-town, Li Liuru (c1931–2007, known simply by his given name Liuru; photo above), was pitiable. His eyes went bad when he was 4 sui. His poor family was always on the move, renting rooms. He “did nothing” at home till “learning gujiang” around 18 sui (c1948), but he really liked listening to gujiang before he took it up. He learned with the band in Xiejiatun village just north of the town, a distinguished group whose most famous player in modern times was Yu Fucai (c1925–68). Liuru studied as an apprentice in the Xiejiatun band for three years, and then did another three years for free (“studying three years, repaying three years”), as tradition prescribed; when there wasn’t much business, he played for other bands too, but Yu Fucai’s band was most in demand.

Liuru stopped playing in the Great Leap Forward “because the officials wouldn’t let us play”, and he apparently then played little until after the Cultural Revolution. He only played the lower part, and was not regarded as an outstanding gujiang. Liuru had four brothers and sisters, but they were “all useless”, and the family had no contact. He did manage to find a wife, though, when he was almost 30—also blind, she was a water-seller. The fate of blind girls was even more pitiable: their only hope was begging, and their life expectancy was even shorter than that of blind men.

Erhur

Another young blindman who apprenticed himself to Yu Fucai was Erhur (real name Wang Hui, b.1946). A wonderful man, he has a deep knowledge of the “old rules” and an exceptional love for music: his face becomes a pool of adoration when he recites the gongche solfeggio outlines of the old suites.

Erhur, 2003.

Like Liuru, Erhur’s family lived in Yanggao town. He went blind at the age of 3 sui. When he was 12 sui his mother took him to a hospital in Datong; realizing his sight couldn’t be cured, he resolved to seek a way of making a living. They then bought a dizi flute for 36 fen at a Datong stationery shop (there were no instrument shops then). “It took me ages to get a note out of it, but once I did, I didn’t dare take it from my lips,” he recalled. “I played anything I heard, popular folk-song melodies like Anbanshang kaihua.”

Neighbours knew Erhur played well, so one New Year the neighbourhood committee asked him to represent them for a secular county festival. He was a bit apprehensive, but played. There were also an erhu player and a banhu player who played a version of the popular folk-song Wuge fang yang 五哥放羊. He tried to play along with them but found he couldn’t. The erhu player explained it was all to do with tuning! Still, he won a prize of 20 jin of frozen radishes, then worth the princely sum of 2.5 kuai.

This strengthened Erhur‘s resolve to take up music, so he bought a rudimentary erhu in Yanggao town, made from a tin and a stick, costing 4 mao. He soon picked it up, and began getting the hang of scales. He still wanted to learn more instruments. Around 1959, when he was 14 sui, he bought a decrepit sheng mouth-organ for 10 kuai. After taking it home and piecing it together, he began practising “small pieces” like Shifan. All this, remember, at the height of the Great Leap Forward and famine, which were not part of Erhur’s account.

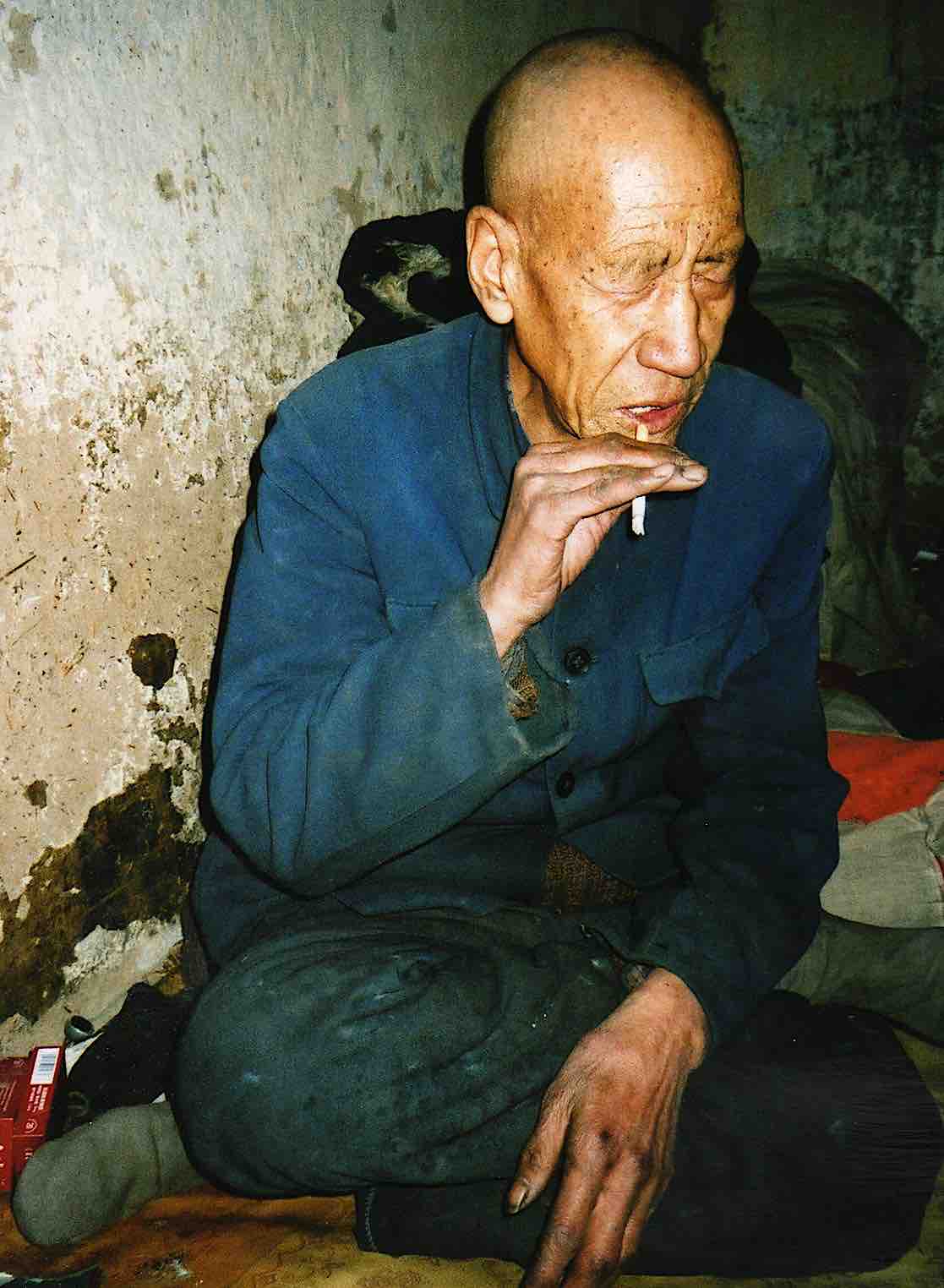

Erhur first spent some time learning with a gujiang called Siban (surname Zhang) in Jinjiazhuang village—for whose band the renowned yinyang household Daoist Liu Zhong also played occasionally when ritual business was sparse during the Cultural Revolution. But after hearing Yu Fucai’s band doing a funeral in town, Erhur asked his parents if he could switch over to Yu as “disciple transferring to another household” (guomen tudi). By this time Yu Fucai was the “main beam” (zhengliang 正梁) of the Yu family band in Xiejiatun village. His fee to take a disciple was 100 kuai a year. Erhur lived at Yu’s house around twenty days a month—the learning process naturally involves taking on the whole gujiang lifestyle. Masters had no way of teaching, pupils just picked it up as they went along; Erhur could only hear his master playing when they performed for ceremonials. He learned along with his master’s oldest son; they got along well at first, but then when Erhur learned faster, the son was always getting criticized, so their relationship deteriorated. Every morning the son was reluctant to get out of bed and go with Erhur into the fields to practise; while Erhur practised, the son would go and look for firewood to make a fire to keep warm.

Yu Fucai’s gujiang father was a hard case, always conning, robbing, and beating people up. He spent some time in prison and eventually, in the 1940s, got his head smashed in with a hammer. Before Liberation gujiang were commonly given opium to smoke by the host family to help them play better. But Erhur knew that addiction was a danger—he had heard of gujiang who had to sell their roof-beams or demolish their outhouse in order to get a fix. Yu Fucai himself had been locked up in an opium-prevention cell for a year soon after Liberation, still only in his teens, and by the time Erhur was studying with him, opium was hard to come by.

As collectivization began to be implemented from 1954, many Yanggao people took refuge further north. Two of Yu Fucai’s uncles fled to Shangdu in Inner Mongolia, and there are still many craftsmen from Yanggao around Hohhot and Baotou.

Yu Fucai had eight children, a heavy responsibility. Erhur had to ask him to recite the gongche solfeggio in the evenings after he got back from the fields. In the mornings after he had practised, he would do chores for his master like milling, fetching water, and ploughing. There were so many mouths to feed that all the flour you milled in a morning was only enough for one meal. In 2003 three of Yu Fucai’s sons, as well as a nephew, were still active as gujiang in Xiejiatun.

Session at Xiejiatun, 2003.

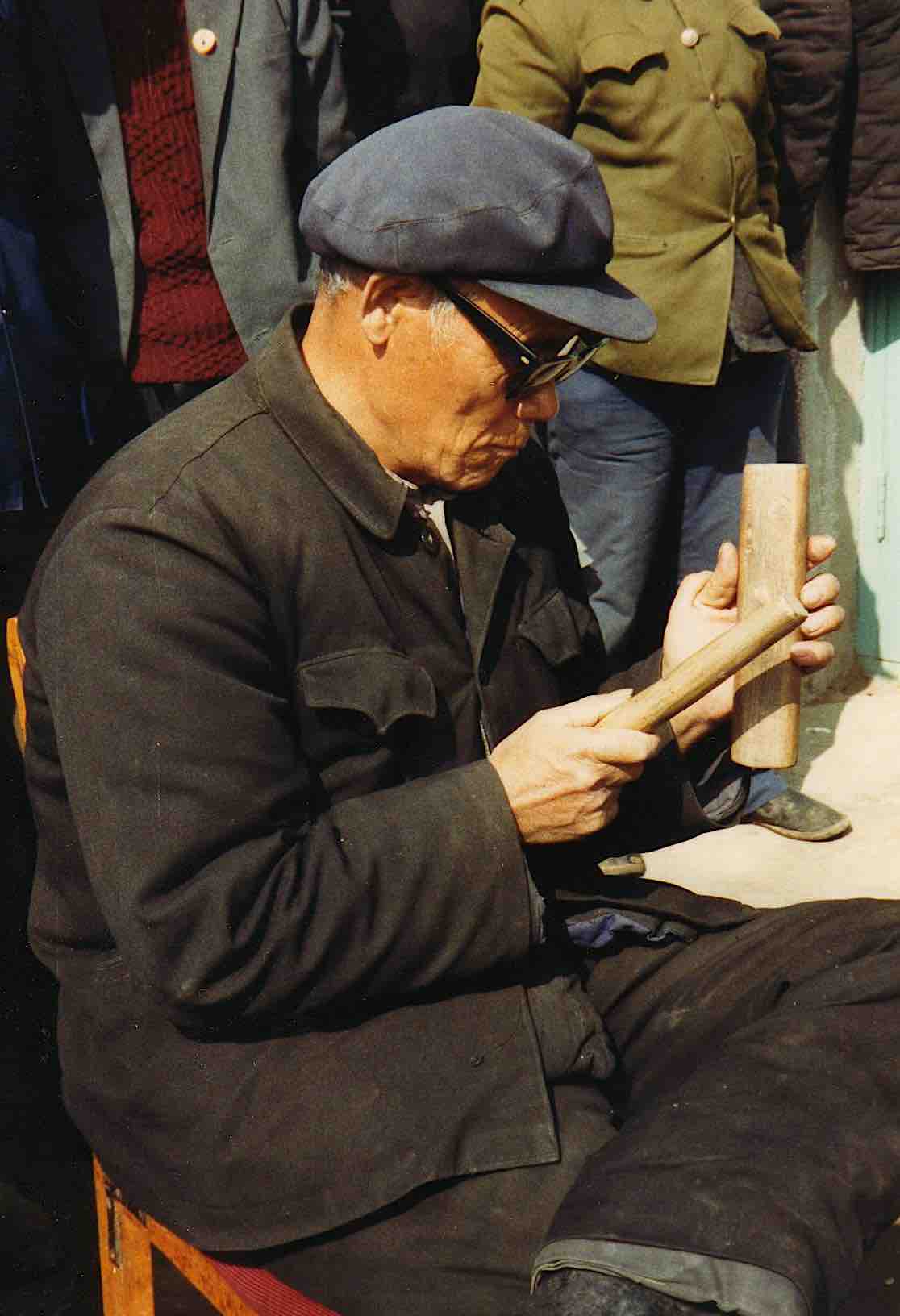

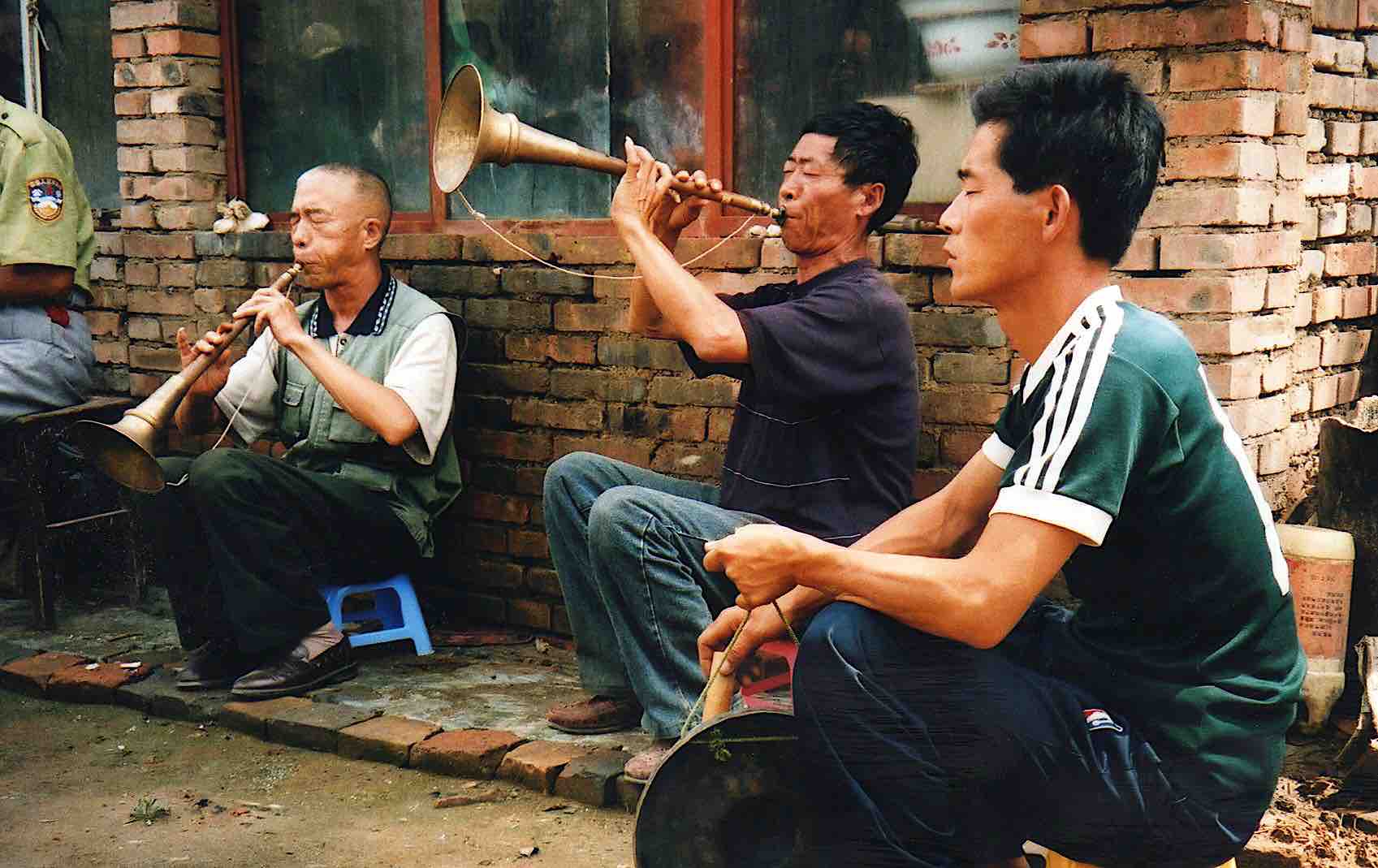

If all was not all sweetness and light in the Hua family band, gujiang relations in Xiejiatun sound still more fraught. Several gujiang from Xiejiatun apprenticed themselves to the Hua family: one Erxianr (surname Xie) from Xiejiatun got into a feud with the Yu family, so he made a point of antagonizing them by going over to Hua Fa as “disciple crossing the gate”. Another blindman, Duan Guanming (b. c1927, known as Liuzhi “Six fingers” as he had an extra finger on one hand), also came from Xiejiatun, but got on better with Hua Yinshan than with the Yu family—we found him playing in Hua Yinshan’s band in 1991.

Duan Guanming on woodblock, 1991.

Erhur came back to the county-town when he was 18 sui (c1963) to set up his own band, taking disciples. Hua Yinshan didn’t mention this, but in his teens he sometimes played for Erhur’s band these next couple of years; he only played sheng at first, but was beginning to get the hang of the shawm too. There was also a great player in Erhur’s band called Little Jinxi (surnamed Wang), from nearby Qingshunbu. For the operatic pieces played in the afternoon of funerals, he used to play two kouqin whistles at once, making a big sound that drew the crowds. He died on the eve of the Cultural Revolution aged only 41 sui, coughing up blood in the middle of playing—an alarmingly common and prestigious way for shawm players to die.

Yin San

Meanwhile, another blindman was “learning gujiang” in the town. Like Erhur, Yin San (b. c1947) played dizi flute when young. He began learning shawm from 16 sui (c1962) with the blind town gujiang Song Chengxin. Yin San also studied at some stage with a gujiang in Wangguantun township, learning the gongche solfeggio of the shawm pieces from him—which he later forgot.

Yin San (right) with Liuru, 2003.

Yin San and Erhur both had town registration, and were blind, so they did not have to apply for leave of absence from any production-team or hand over any money to them, unlike village-registered gujiang. Moreover, their ceremonial activities were tolerated more readily by cadres; blindmen could put all their energies into being gujiang, so they could do well. Yin San recalled that in the early 1960s a band got around 5 kuai for an afternoon, 8 kuai for playing all day, 10 kuai including the burial procession next morning. Erhur claimed that while most bands could earn about 12 kuai a day, his own band was so admired that he could charge 22 kuai. In fact payments were only calculated in terms of cash, they were still paid in food: peanuts or gao paste, 1 jin or half a jin each per day—Yu Fucai’s hemp sack was tough from the oil.

But even sighted village bands could still get permission from their production-team to go out on business. The Xiejiatun band earned a dozen kuai a day then, of which they had to give the commune 1.5 kuai each day they were away, in return for one whole work-point each. The band boss Yu Fucai took 15 shares of the fee plus 10 shares for providing the instruments, while everyone else got 10 shares. Yu only used one or two musicians from outside his own family, so it was worth it. Doing funerals they got to eat out for free too, and didn’t have to till the communal fields all the time, so it was a better life than being a peasant.

Still, I can’t quite build a consistent picture from such accounts of gujiang business before the Cultural Revolution. They articulated no clear distinction between the various periods from 1949 to 1966, though I surmise that business must have been easier before collectivization around 1954, and again briefly during the lull in campaigns from around 1961 to 1964. Yin San claimed rosily, “Before the Cultural Revolution business was even better than today, around twenty days a month—there weren’t so many gujiang then, so there was more work to go round.” But he only took part in the life from the early 1960s.

Conversely, Liuru, who was trying to make a living through the 1950s, said times were tough. Erhur pointed out that there was less business under Maoism than either before Liberation or since the 1980s reforms, because people had less money; one death provided no more than three days’ work in all, whereas earlier and later, taking into account all the subsidiary observances before and after the funeral proper, it might provide up to ten days’ work. He reckoned that in the 1950s, bands might go out on business seven or eight times a month, or “every three days or so”.

They agreed that despite all the famine deaths around 1960, there wasn’t so much business then—if people had any money at all, they’d buy something to eat, not invite gujiang. Liuru recalled that for funerals during the famine years, people could only put out a couple of mantou bread rolls on the altar table before the coffin; whenever there was a death, work-teams turned up to prevent gujiang playing and stop the family burning paper spirit-money, on pain of a fine. Indeed, in Yanggao the famine continued until at least 1965, and people were hungry right into the late 1970s. Still, I think we have to assume a slight and temporary improvement in people’s lives in the early 1960s when Erhur and Yin San set up in business.

The Hua band

In Yangjiabu village just north of the county-town, Hua Fa (1917–87), father of Yinshan and Jinshan, was much admired as a gujiang. His nickname was “Heavenly dragon” (Tianlong); soon he was simply known as “Great gujiang” (Da gujiang). He was also known as “Sighted Fifth brother” (Zhengyan wugar) or “False Fifth brother” (Jia wugar), by contrast with another famous blind gujiang in Zhenmenbu village just further east called “Blind Fifth brother” (Xia wugar, surnamed Xue) or “True Fifth brother” (Zhen wugar)—“true” and “false” alluding to the fictional character Monkey. There was no love lost between rival bands: “True Fifth brother” was murdered by a rival gujiang while they were performing for a funeral in the 1940s.

Hua Yinshan’s second uncle Hua Yi, known as “Second gujiang” (Er gujiang), also smoked opium. Their drummer was a blind man—Hua Fa was also a fine drummer. The celebrated gujiang Little Jinxi, from nearby Qingshunbu, sometimes played for Hua Fa band as well as for Erhur. The Hua band had a long-standing feud with the Xiejiatun band, though some Xiejiatun men preferred to come over to Hua Fa’s band, like blindman Duan Guanming, long a regular recruit. Another disciple of Hua Fa was known as “Second Dragon” (Erlong), from Yaozhuang village just east.

Duan Guanming accompanying Hua Yinshan in trick repertoire, 1991:

note Yinshan’s cloistered daughter.

Hua Yinshan claimed he became the “main beam” of the family band on large shawm from the age of 17 sui (c1964). He had heard the classic suites in the family band for many years, but had apparently only just begun playing them on large shawm.

Hua Yinshan was also working with several other bands in this period, with his father’s blessing, as the family needed all the work they could find. He spent some time in the bands of blindmen Erhur and Yin San, both based in the county-town, playing the lower part on shawm, as well as the sheng mouth-organ and the drum. As we saw, Erhur was a disciple of Yu Fucai’s band in Xiejiatun; the Yu band had a long-standing feud with the Hua band, but there was always some interplay.

Apart from the county-town and the villages of Yangjiabu and Xiejiatun, nearby Guanjiabu was the base of another fine gujiang band. The senior gujiang Shi Youtang (d. c1998) had a blind disciple called Shi Zhenfu, a distant relative of his (though their surnames were different Shi characters); he was known as Errenr “Two people”! Both led bands into the 1980s. Another blindman from Guanjiabu, called Yinhur (surname Li), became a disciple of Hua Fa.

Hua Yinshan told me the story of his father’s no.1 large shawms. In the 1940s a blindman called Chanxi in Guanjiabu wanted to buy a pair of shawms. An itinerant shawm maker called Wang Lianguo had moved from Yuxian in Hebei to Chenjiabu, near Yangjiabu. He went to Chanxi’s house to sell him a pair of shawms—this would have been around 1945, when Hua Fa was in his early 30s, between the births of Jinshan and Yinshan. But Chanxi didn’t know how to choose them, so he asked Hua Fa to help him. After Chanxi died, he left the wooden bodies of his shawms to his daughter, who later sold them to Yinshan.

Over twenty-six days in 1989, as part of their work for the Anthology, the Yanggao Bureau of Culture used their limited equipment to make a whole series of precious cassette recordings of the most distinguished shawm bands, including those of the Hua family, Shi Ming in Wangguantun, and Yang Deshan (father of Yang Ying) in Gucheng, as well as the bands of Xiejiatun, Guanjiabu, Luowenzao township, Qingshunbu, and Greater Antan (see my Ritual and music of north China: shawm bands in Shanxi, p.49).

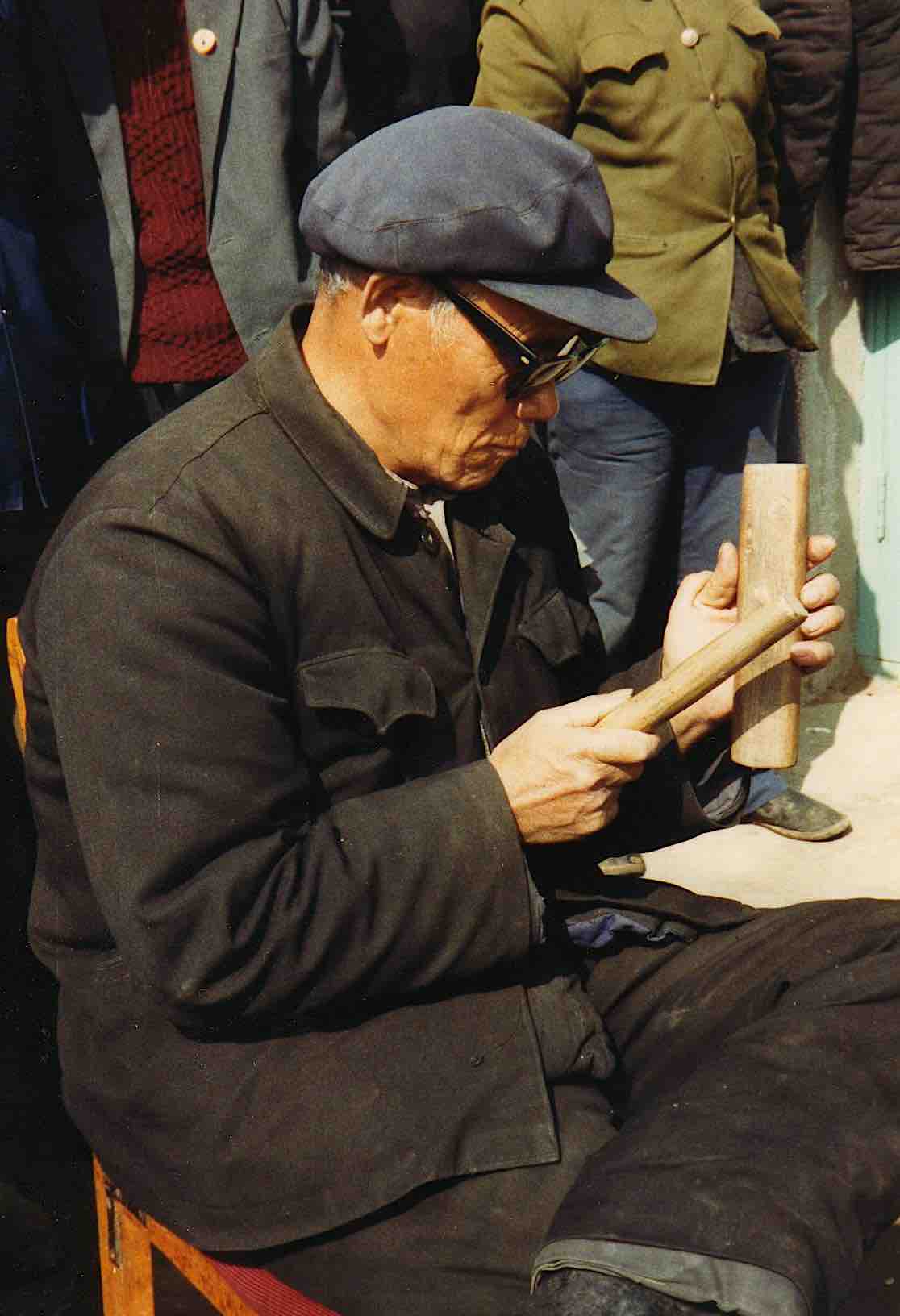

Li Zhonghe

South of the county-town in Shizitun township, yet another celebrated blind gujiang was based in Yaozhuang village. Li Zhonghe (1908–88), known as Second Kid (Erwa 二娃), went blind at the age of 5 or 6 after an itinerant doctor tried to cure his ailing eyes by putting eggshell over them. Li Zhonghe learnt sheng and shawm from 15 sui, sometimes making up a band with an outstanding gujiang called Wantai (surnamed Cui) from Zhouguantun village nearby. Li had two younger colleagues (shidi) in his village, the brothers Fan Liang and Fan Gao.

Around 1952, after the death of Li Zhonghe’s first wife, he married a widow who already had a son and daughter. The son Li Bin (b.1945, not the same as his namesake, Li Manshan’s son!) played percussion in his stepfather’s band from around 1955, and began learning sheng and shawm, as well as gongche solfeggio, with him about four years later. Li Bin claimed his stepfather’s band didn’t stop playing through the Great Leap Forward or the ensuing famine.

Since the reforms

The collapse of the commune system from the late 1970s allowed an impressive revival of tradition (for the Daoists, see e.g. here). But by 2003 the scene was changing further. Erhur was still leading a band, having readily taken pop on board. He and his wife made a handsome couple, and had a lovely clean household in town—though their son, who managed to enter the police force despite (or by dint of?) a dubious reputation, was a worry. Erhur claimed to be able to perform the three suites that we couldn’t track down; but he was later reluctant to recite or perform them for us, perhaps worrying about my relationship with his rival Hua Yinshan.

Yin San, also married, was getting 90 kuai a month from the government disability benefit, and still led a band, usually playing cymbals. Of his two pupils, the younger had been with him for eight years. They could play the few traditional pieces still required for rituals, and Yin San felt no need to transmit the ones that weren’t. After his fine drummer Ling Dawenr (b. c1924) retired, Hua Jinshan had no competition.

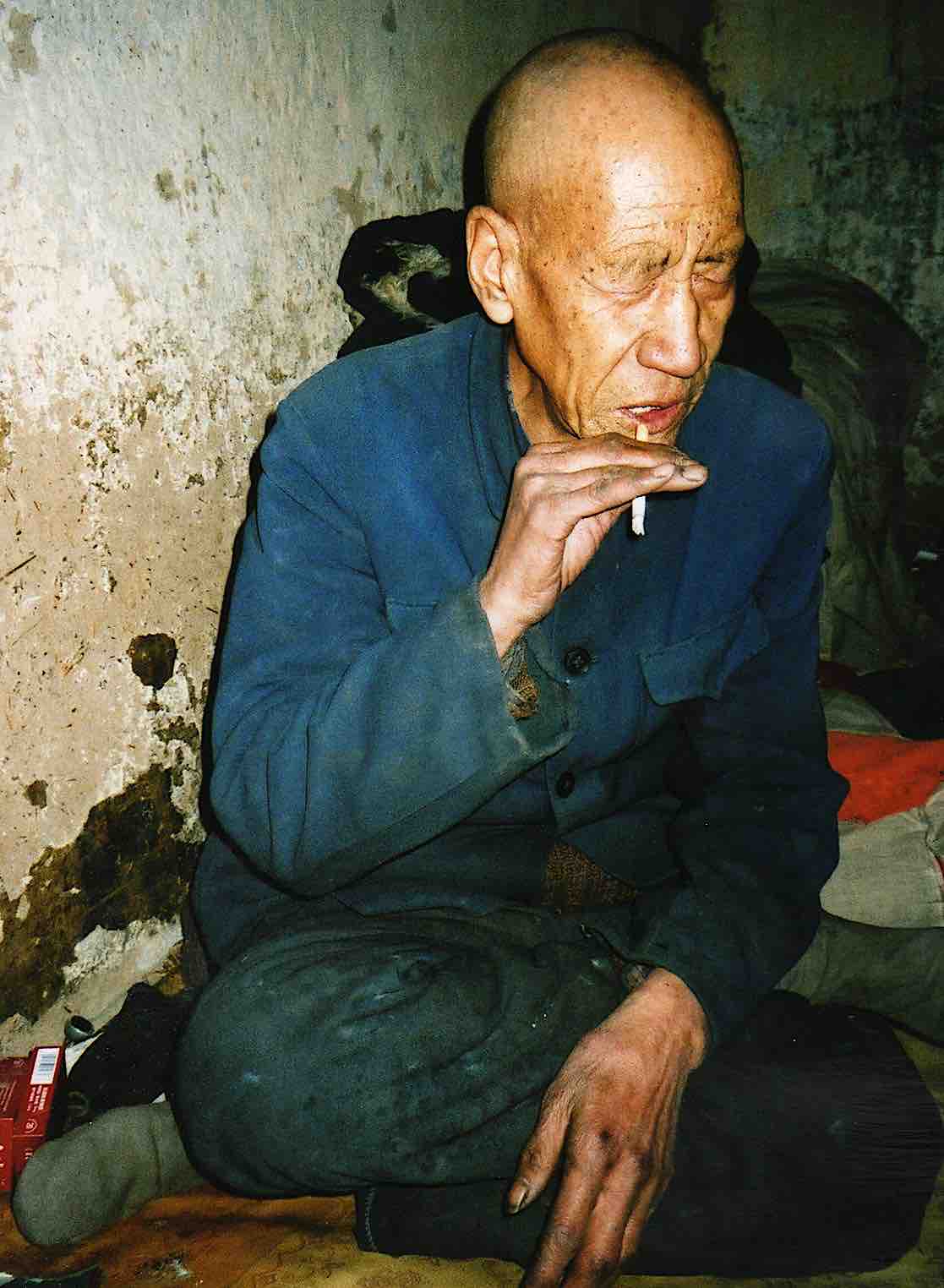

Liuru hadn’t played since around 1988. Now he reckoned that only sighted people could do business (chixiang 吃香, a common term for popularity)—no-one wanted blind people any more. Erhur and Yin San were still doing well by adapting; they were a bit younger, more enterprising, and had more of a reputation as musicians. But he was right that in a cut-throat pop market, blindmen were no longer able to hold their own as gujiang without a solid support network.

The decrepit little shack where we found Liuru living in 2003 had been his “base area” for over thirty years; he bought it with the little money that remained when his parents died. His registration was at Xibei village commune, from whom he got 60 kuai a month benefit; as an urban resident his wife (also blind) got 90 kuai. Since giving up the shawm in 1990 Liuru had survived by begging the left-overs from restaurants, but led a pitiful life. He had no contact with his brothers and sisters, and just before we met him his wife had “gone crazy” and he had seen fit to lock her in an outhouse.

Such is the disturbing fate of a lovely senior musician who could still recite the gongche solfeggio of the eight suites more fluently than any other gujiang in the area. Listening to him as he sat cross-legged on the kang brick-bed which takes up most of the space in his pathetic little room, his eyes vacant yet placid as he spoke with dignity and insight of his days as gujiang, would be an upsetting experience for the most hardened fieldworker.

Li Zhonghe’s stepson Li Bin is an exceptional case. Unusually for a gujiang family, Li Bin did quite well in school. Though intermittently active as gujiang through the early years of the Cultural Revolution, around 1970 he went off to work in the coal mines of Datong city, becoming a cadre there, only resuming gujiang business again when he retired in 1996.

Li Zhonghe had taken up as a gujiang again after the reforms, and was still playing right until his death in 1988. He had a blind disciple (younger brother of talented young yinyang Wu Mei) who showed great promise as a gujiang, but he had only been learning for a few months when Li Zhonghe died. Li Bin now wanted to complete his stepfather’s mission in helping him learn, but the disciple soon decided against becoming a gujiang. However, Li Bin soon found another promising disciple.

By 2003 Li Bin had handed over the leadership of the band to Yu He (Quanmin, b. c1960) who played drum and yangqin; he only took up the business after being demobbed from the army in 1984. So the band was now based at Yu He’s home of Fanjiatun village nearby in Tianzhen county. Yu He’s son Chunbo (known as Bobo, like Hua Yinshan’s grandson; b. c1987) became Li Bin’s only pupil, learning since 2001. Li Bin could afford to be choosy; his criterion for accepting a pupil was that they have to be “of good character” (renpin)—an unlikely demand for a gujiang. After leaving primary school, Bobo “wasn’t interested in anything”, so his dad took him along with the band to show him how tough it was making a living; but Bobo fell in love with the life and became a brilliant musician. Though he mainly played pop, Li Bin also taught him pieces from the traditional repertory.

Li Bin (left) with Wu Fan, 2003.

Li Bin is at a certain remove from the tradition, far more educated than most gujiang, and quite articulate. Living in Yanggao county-town, his house is comfortable, and the family is quite well-off. His wife became a Protestant around 1993; Li Bin was still at the mines, and she had a tough time having to look after their three children all alone, with no-one to talk to. Li Bin (not himself a believer) sometimes set Protestant lyrics to pop songs for her to use in church. Sincere and curious to study local traditions, he made a rather ideal co-fieldworker.

We saw how gujiang, outcasts in the “old society”, have gradually become rather more assimilated into society, first by being forced into a sedentary agricultural life under the communes, and then by the equality brought by earning power since the reforms. Along with their outcast status before Maoism came a lack of education or upward mobility. Among gujiang families, Li Bin was exceptional in doing relatively well at school, and even more so in finding a job as a cadre. Still more surprising is that having apparently escaped from the lowly life, he then chose to return to it after retirement. In his case, apart from supplementing his pension and giving him something to do, he feels a genuine enthusiasm for the music he learnt from his stepfather in his youth, only tempered now by its rapid loss under the assault of pop music.

Meanwhile Li Bin has been painstakingly making emic transcriptions of his father’s repertoire (both the suites and the many “little pieces” also formerly required for particular ritual segments), writing a 126-page score with parallel gongche solfeggio and cipher notation. While scholars (myself included) have transcribed the Yanggao shawm suites, this is a unique labour of love from a performer.

Very few gujiang could graduate to the world of urban troupes (for Shi Ming’s brief sojourn in Datong, see here), and while most sons of gujiang were now inclined to seek a more respectable profession, other poor village boys might still see it as a better option than tilling the fields—all the more now that learning pop music is less demanding than the traditional training. Today gujiang bands are often in the age-range of 15 to 45. Their main repertory is pop, besides Jinju and Errentai opera pieces and a dwindling repertory of traditional shawm pieces still required to maintain a façade of ceremonial propriety.

Li Sheng, 2018.

The two Li families (those of Li Zhonghe and the Li family Daoists) have long been on good terms. The great Li Qing sometimes played in Li Zhonghe’s shawm band in the 1970s, when Daoist ritual was on hold. Li Bin’s younger stepbrother Li Sheng (b.1954) learnt suona and sheng from his early 20s upon the revival, spending some years as disciple of Hua Yinshan. He did some petty trade in Datong, as well as doing, returning around 2000. Gradually he gravitated to playing sheng with the Li family Daoists; he has long been a regular member of Li Manshan’s band.

I introduced Zhang Quan, a rather younger semi-blind gujiang in Pansi village whom I’m always happy to see, in these vignettes of the diverse personalities from whom we learned in Yanggao.

* * *

In some other parts of north China (like the Northeast, or Shandong) shawm bands have long and prestigious hereditary traditions, but here, as in Shaanbei, few bands can trace their history back more than three generations—though their classic suite repertoire is more ancient. Note that rather few gujiang live to old age; until the 1950s many were blind, smoked opium, and died young, and it is still quite unusual to find gujiang still playing in their 60s; anyway, opium-smoking blindmen from a despised caste found it hard to set up a family. By the early 21st century senior gujiang were still happy to take disciples, but as it is a low-status occupation they didn’t necessarily encourage their own sons to learn, hoping they would get an education and a proper job instead. If this is true today, there was less choice in the past, with education even rarer and job opportunities fewer.

While sighted players also deserve recognition as gujiang, and suffered from similar discrimination, blindmen formed the core of many Yanggao bands right until the 1990s. Since then they have become less common, along with the whole rich culture of shawm bands in north Shanxi.

But I still cherish the memory of these blind shawm players—outcasts who embodied the wealth of traditional folk culture that somehow survived down to the eve of the 21st century, dovetailing with the rituals of the household Daoists. With their deep experience of the “old rules” of ceremonial, far from the abstruse erudition of the literati who dominate sinology, they were among the main transmitters of imperial Chinese culture, who should be esteemed.

Thomas Hart Benton, The sources of Country music (1975).

Thomas Hart Benton, The sources of Country music (1975).

《 映旭斋增订北宋三遂平妖全传》 第十七回插图

《 映旭斋增订北宋三遂平妖全传》 第十七回插图

While I played

While I played

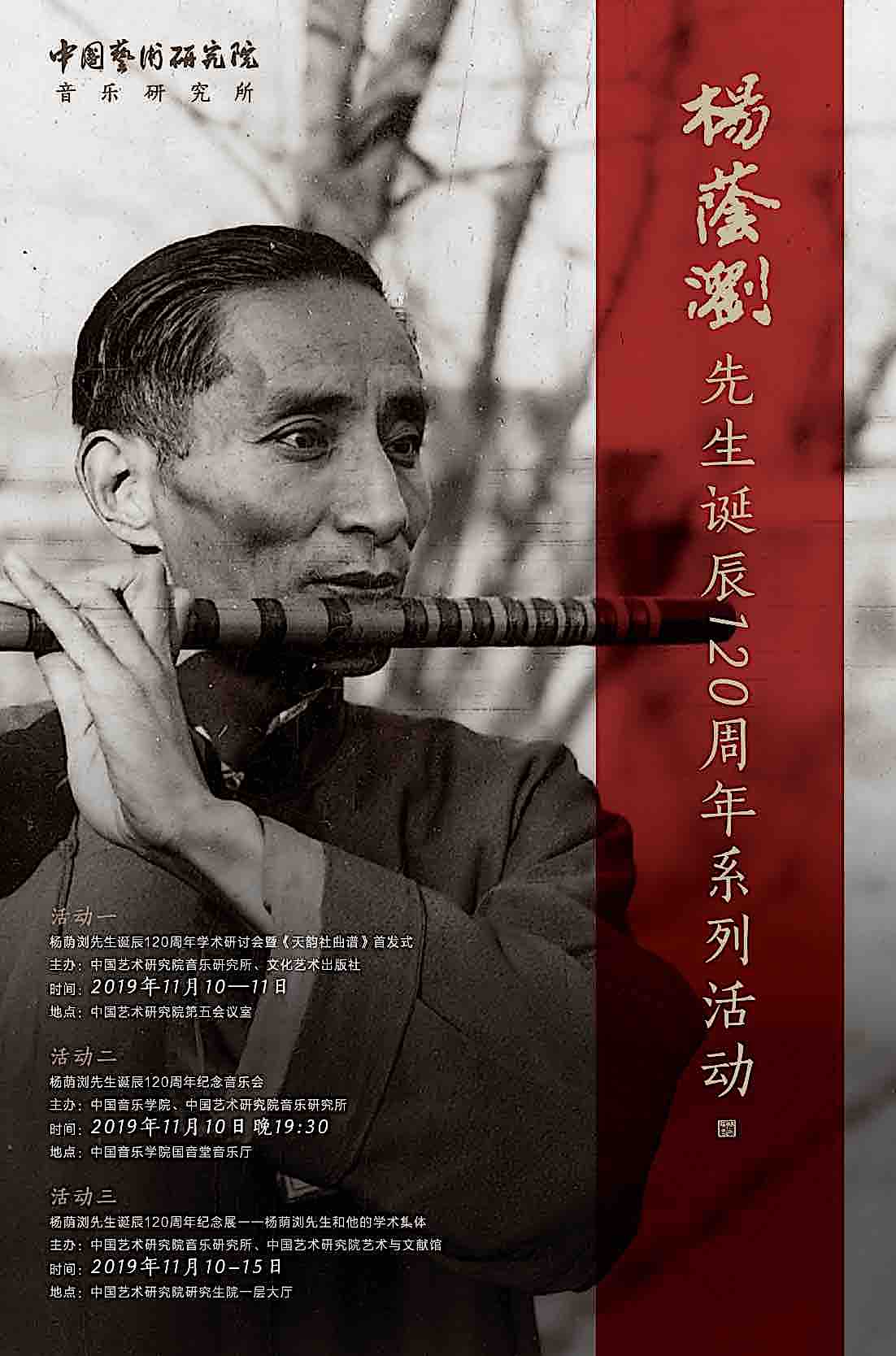

He excelled not only as a historian but as fieldworker and performer, steering the Music Research Institute through the choppy waters of Maoism. I’ve devoted a

He excelled not only as a historian but as fieldworker and performer, steering the Music Research Institute through the choppy waters of Maoism. I’ve devoted a

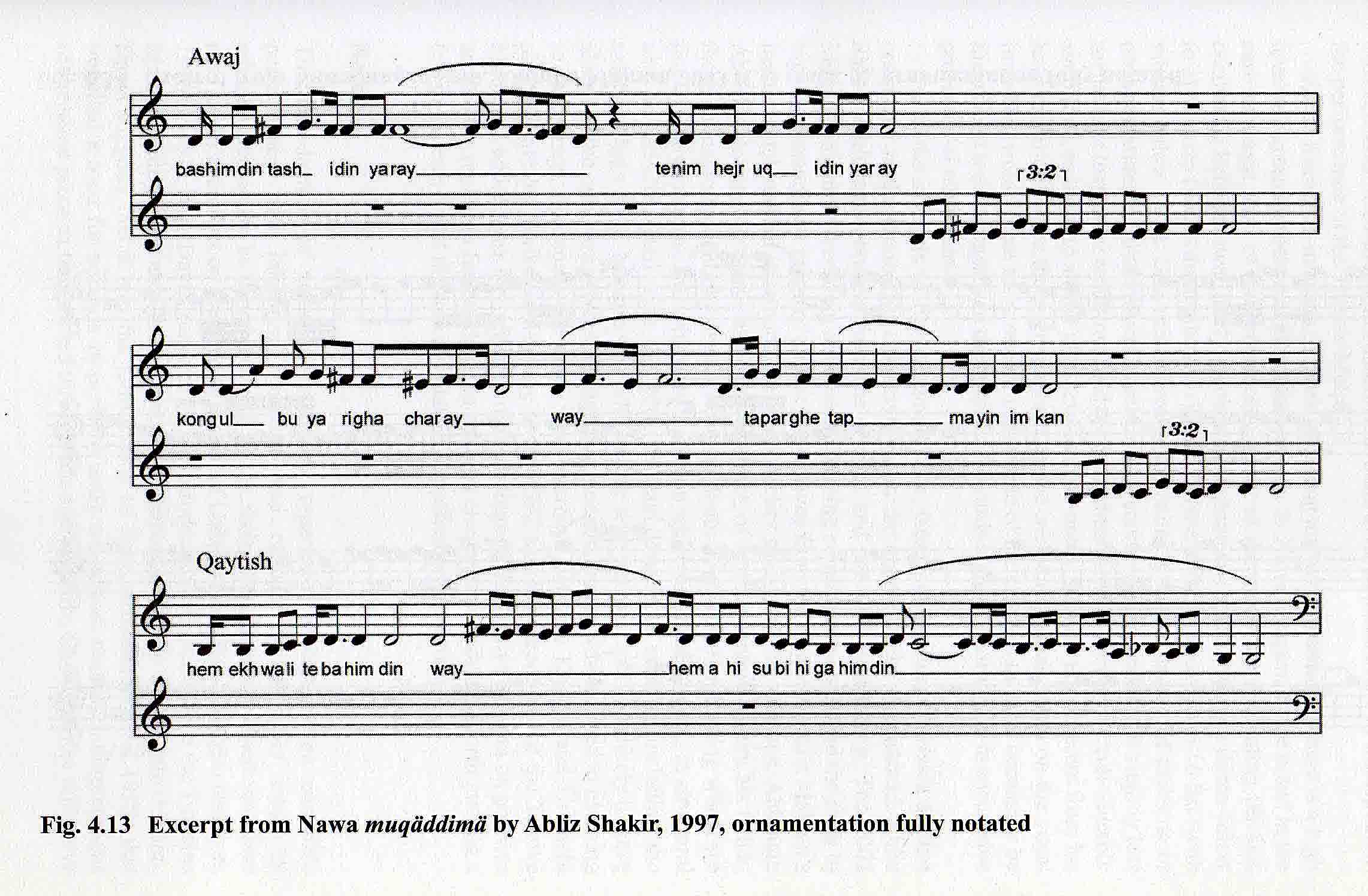

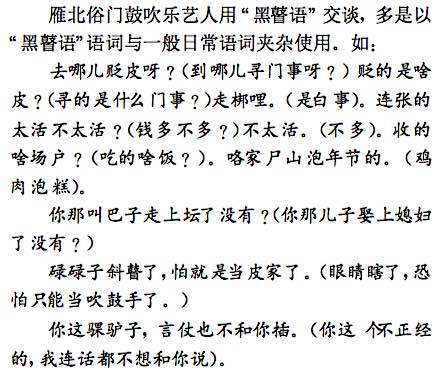

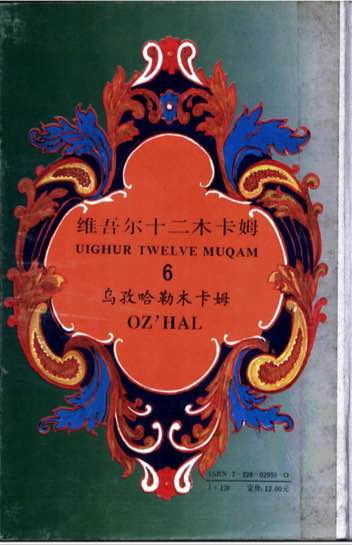

In Xinjiang the liberalisations following the collapse of the commune system from 1979 allowed the resumption of both folk activity and official research. Furthering the work that had begun in the 1950s, a Muqam Research Committee was formed in 1979, soon incorporated into the Xinjiang Muqam Ensemble. They went on to produce major series of recordings and transcriptions. Meanwhile the compilation of the

In Xinjiang the liberalisations following the collapse of the commune system from 1979 allowed the resumption of both folk activity and official research. Furthering the work that had begun in the 1950s, a Muqam Research Committee was formed in 1979, soon incorporated into the Xinjiang Muqam Ensemble. They went on to produce major series of recordings and transcriptions. Meanwhile the compilation of the