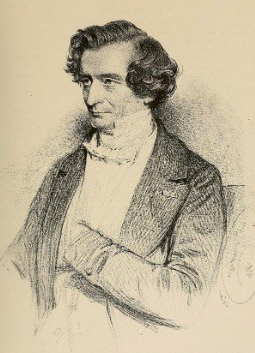

The unflattering views on Chinese music expressed by Berlioz have been much cited. He may have been an iconoclast within his own culture, but it would be asking too much to expect his horizons to transcend the limited aesthetics of his day.

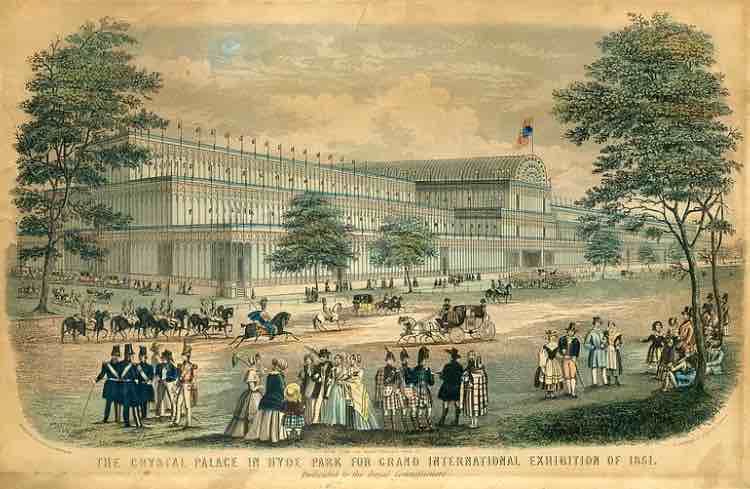

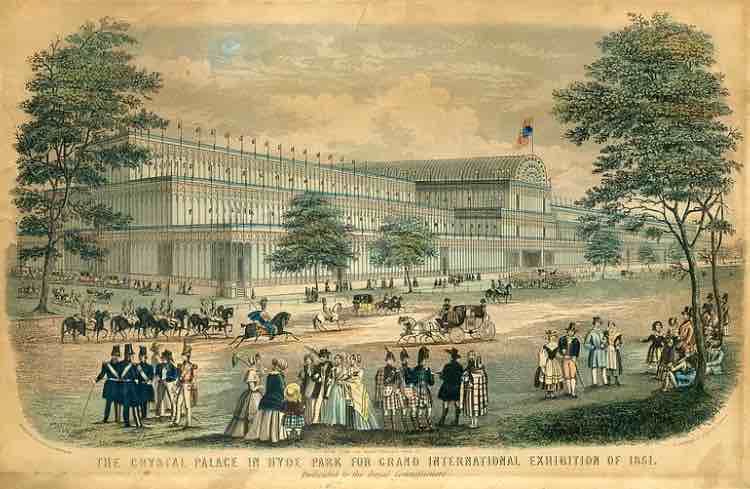

In The Cambridge companion to Ravel, Robert Orledge cites Berlioz’s comments on hearing Chinese musicians at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London in 1851—only a few years after the Opium Wars:

The melody, which was altogether grotesque and atrocious, finished on the tonic, like our most undistinguished sentimental songs [!]; it never moved out of the original tonality or mode. […] Nevertheless, the ludicrous melody was quite discernible, and one could have written it down in case of real need [!].

And as Orledge comments, his conclusion, after listening to a wider range of exotic musicians, was that

Chinese and Indian music would be similar to ours if it existed [WTF]; but that, musically speaking, these nations are still plunged in a state of benighted barbarianism and childish ignorance where only a few vague and feeble instincts are dimly discernible; that, moreover, the Orientals call music what we should style cacophony, and that for them, as for Macbeth’s witches, foul is fair.

Another passage has been translated thus:

As for the Chinaman’s voice, I have never heard anything so strange in my life—hideous snorts, and groans, very much like the sounds dogs make, when they wake up, stretch their paws and yawn with an effort.

More sympathetic is this report from the Illustrated London News:

A PLEASING addition has been made to the Chinese Collection, consisting of a Chinese Lady, named Pwan-ye-Koo, with small lotus-feet only 2½ inches in length, a Chinese professor of music, his two children (a boy and a girl), the femme de chambre of the lady, and an interpreter. The children are gay, lively, and intelligent, the lady herself agreeable and interesting, and the gentleman civil and obliging. A Chinese concert forms part of the entertainment: the lady Pwan-ye-Koo singing a Chinese air or two, accompanied by the professor, who likewise treats the public with an exhibition of his vocal powers. The group is one that has much to commend it: it is picturesque and peculiar, and presents an image in high relief of the native manners of a Chinese family. The conduct of the domestic blended the humble and the familiar in a significant manner; and there was an air of freedom, and a sense of mutual obligation manifested in the whole party, calculated to make a favourable impression on the spectator.

They even had an audience with Queen Victoria at her summer retreat of Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

Still, if we read the full passage, Berlioz did at least make an effort. Further to A French letter, here’s some more language practice [sections between asterisks translated above]:

A propos de cantatrice, j’ai enfin satisfait le désir que j’avais d’entendre la fameuse Chinoise, the small-footed lady (la dame au petit pied), comme l’appelaient les affiches et les réclames anglaises. L’intérêt de cette audition était pour moi dans la question relative aux divisions de la gamme et à la tonalité des Chinois. Je voulais savoir si, comme tant de gens l’on dit et écrit, elles sont différentes des nôtres. Or, d’après l’expérience assez concluante que je viens de faire, selon moi, il n’en est rien. Voici ce que j’ai entendu. La famille chinoise, composée de deux femmes, deux hommes et deux enfans, était assise immobile sur un petit théâtre dans le salon de la Chinese house, à Albert gate. La séance s’est ouverte par une chanson en dix ou douze couplets, chantée par le maître de musique, avec accompagnement d’un petit instrument à quatre cordes de métal, du genre de nos guitares, et dont il jouait avec un bout de cuir ou de bois, remplaçant le bec de plumes dont on se sert en Europe pour attaquer les cordes de la mandoline. Le manche de l’instrument est divisé en compartimens, marqués par des sillets de plus en plus rapprochés au fur et à mesure qu’ils se rapprochent de la caisse sonore, absolument comme le manche de nos guitares. L’un des derniers sillets, par l’inhabileté du facteur, a été mal posé, et donne un son un peu trop haut, toujours comme sur nos guitares quand elles sont mal faites. Mais cette division n’en produit pas moins des résultats entièrement conformes à ceux de notre gamme. Quant à l’union du chant et de l’accompagnement, elle est de telle nature, qu’on en doit conclure que ce Chinois-là du moins n’a pas la plus légère idée de l’harmonie. *L’air (grotesque et abominable de tout point) finit sur la tonique, ainsi que la plus vulgaire de nos romances, et ne module pas, c’est-à-dire (car ce mot est généralement mal compris des personnes qui ne savent pas la musique) ne sort pas de la tonalité ni du mode indiqués dès le commencement.* L’accompagnement consiste en un dessin rhythmique assez vif et toujours le même, exécuté par la mandoline, et qui s’accorde fort peu ou pas du tout avec les notes de la voix. Le plus atroce de la chose, c’est que la jeune femme (la [small-]footed lady), pour accroître le charme de cet étrange concert, et sans tenir compte le moins du monde de ce que fait entendre son savant maître, s’obstine à gratter avec ses ongles les cordes d’un autre instrument de la même nature, mais au manche plus long, sans jouer quoi que ce soit de mélodieux ou d’harmonieux. Elle imite ainsi un enfant qui, placé dans un salon où l’on exécute un morceau de musique, s’amuserait à frapper à tort et à travers sur le clavier d’un piano sans en savoir jouer. C’est, en un mot, une chanson accompagnée d’un petit charivari instrumental. Pour la voix du chanteur, rien d’aussi étrange n’avait encore frappé mon oreille: *figurez-vous des notes nasales, gutturales, gémissantes, hideuses, que je comparerai, sans trop d’exagération, aux sons que laissent échapper les chiens quand, après un long sommeil, ils bâillent avec effort en étendant leurs membres.* Néanmoins, la burlesque mélodie était fort perceptible, et je porterai un jour du papier réglé chez les Chinois pour la noter et en enrichir votre album. Telle était la première partie du concert.

A la seconde, les rôles ont été intervertis ; la jeune femme a chanté, et son maître l’a accompagnée sur la flûte. Cette fois l’accompagnement ne produisait aucune discordance; la flûte suivait la voix à l’unisson tout simplement. Cette flûte, à peu près semblable à la nôtre, n’en diffère que par sa plus grande longueur, par son bout supérieur qui reste ouvert, et par l’embouchure qui se trouve percée à peu près vers le milieu du tube, au lieu d’être située, comme chez nous, vers le haut de l’instrument. Du reste, le son en est assez doux, passablement juste, c’est-à-dire passablement faux, et l’exécutant n’a rien fait entendre qui n’appartînt entièrement au système tonal et à la gamme que nous employons. La jeune femme est douée d’une voix céleste, si on la compare à celle de son maître. C’est un mezzo soprano, assez semblable par le timbre au contralto d’un jeune garçon dont l’âge approche de l’adolescence et dont la voix va muer. Elle chante assez bien, toujours comparativement. On croit entendre une de nos cuisinières de province chantant: «Pierre! mon ami Pierre», en lavant sa vaisselle. Sa mélodie, dont la tonalité est bien déterminée, je le répète, et ne contient ni quarts ni demi-quarts de ton, mais les plus simples de nos successions diatoniques, est un peu moins extravagante que la romance du chanteur. C’est tellement tricornu néanmoins, d’un rhythme si insaisissable par son étrangeté, qu’elle me donnera sans doute beaucoup de peine à la fixer exactement sur le papier pour vous en faire hommage. Mais j’y mettrai le temps, et, en profitant bien des leçons que me donnera le chien d’un boulanger voisin de ma demeure, je veux, à mon retour à Paris, vous régaler d’un concert chinois de premier ordre. Bien entendu que je ne prends point cette exhibition pour un exemple de l’état réel du chant dans l’Empire Céleste, malgré la qualité de la jeune femme, qualité des plus excellentes, à en croire l’orateur directeur de la troupe, parlant passablement l’anglais. Les dames de qualité de Canton ou de Pékin, qui se contentent de chanter chez elles et ne viennent point chez nous se montrer en public pour un shilling, doivent, je le suppose, être supérieures à celle-ci presque autant que Mme la comtesse Rossi est supérieure à nos Esmeralda de carrefours.

D’autant plus que la jeune lady n’est peut-être point si small-footed qu’elle veut bien le faire croire, et que son pied, marque distinctive des femmes des hautes classes, pourrait bien être un pied naturel, très plébéien, à en juger par le soin qu’elle mettait à n’en laisser voir que la pointe.

Mais je penche fort à regarder cette épreuve comme décisive en ce qui concerne la division de la gamme et le sentiment de la tonalité chez les Orientaux. Je croirai, seulement quand je l’aurai entendu, que des êtres humains puissent, sur une gamme divisée par quarts de ton, produire autre chose que des gémissemens dignes des concerts nocturnes des chats amoureux. Les Arabes y sont parvenus, au dire de quelques savans; ils ont pour cet art inqualifiable une théorie complète. Je parie que les savans qui ont écrit ces belles choses ne savent rien de notre musique, ou du moins n’en ont qu’un sentiment confus et peu développé. Que la théorie des Arabes existe, cela est fort possible, mais elle n’ôte rien à l’horreur de ce qu’ils font en la mettant en pratique.

La musique des Indiens de l’Orient doit fort peu différer de celle des Chinois, si l’on en juge par les instrumens envoyés par l’Inde à l’Exposition universelle de Londres. Cette collection se compose, 10 d’un grand nombre de mandolines à quatre et à trois cordes, quelques unes même n’en ont qu’une; leur manche est divisé par des sillets comme chez les Chinois; les unes sont de petite dimension, d’autres ont une longueur démesurée; 20 d’une multitude de gros et de petits tambours en forme de tonnelets, et dont le son ressemble à celui qu’on produit en frappant avec les doigts sur la calotte d’un chapeau; 30 d’un instrument à vent à anche double, de l’espèce de nos hautbois; 40 de flûtes traversières exactement semblables à celles du musicien chinois; 50 d’une trompette énorme et grossièrement exécutée sur un patron qui n’offre avec celui des trompettes européennes que d’insignifiantes différences; 60 de plusieurs petits instrumens à archet, dont le son aigre et faible doit rappeler les petits violons de sapin qu’on fait chez nous pour les enfans; 70 d’une espèce de tympanon dont les cordes tendues sur une longue caisse paraissent devoir être frappées par des baguettes; 80 d’une petite harpe à dix ou douze cordes, assez semblables aux harpes thébaines dont les bas-reliefs égyptiens nous ont fait connaître la forme, et enfin d’une grande roue chargée de gongs ou tamtams de petites dimensions, dont le bruit, quand elle est mise en mouvement, a le même charme que celui des gros grelots attachés sur le cou et la tête des chevaux de routiers. Je conclus, pour finir, que *les Chinois et les Indiens auraient une musique semblable à la nôtre, s’ils en avaient une; mais qu’ils sont encore à cet égard plongés dans les ténèbres les plus profondes de la barbarie ou dans une ignorance enfantine où se décèlent à peine quelques vagues et impuissans instincts.*

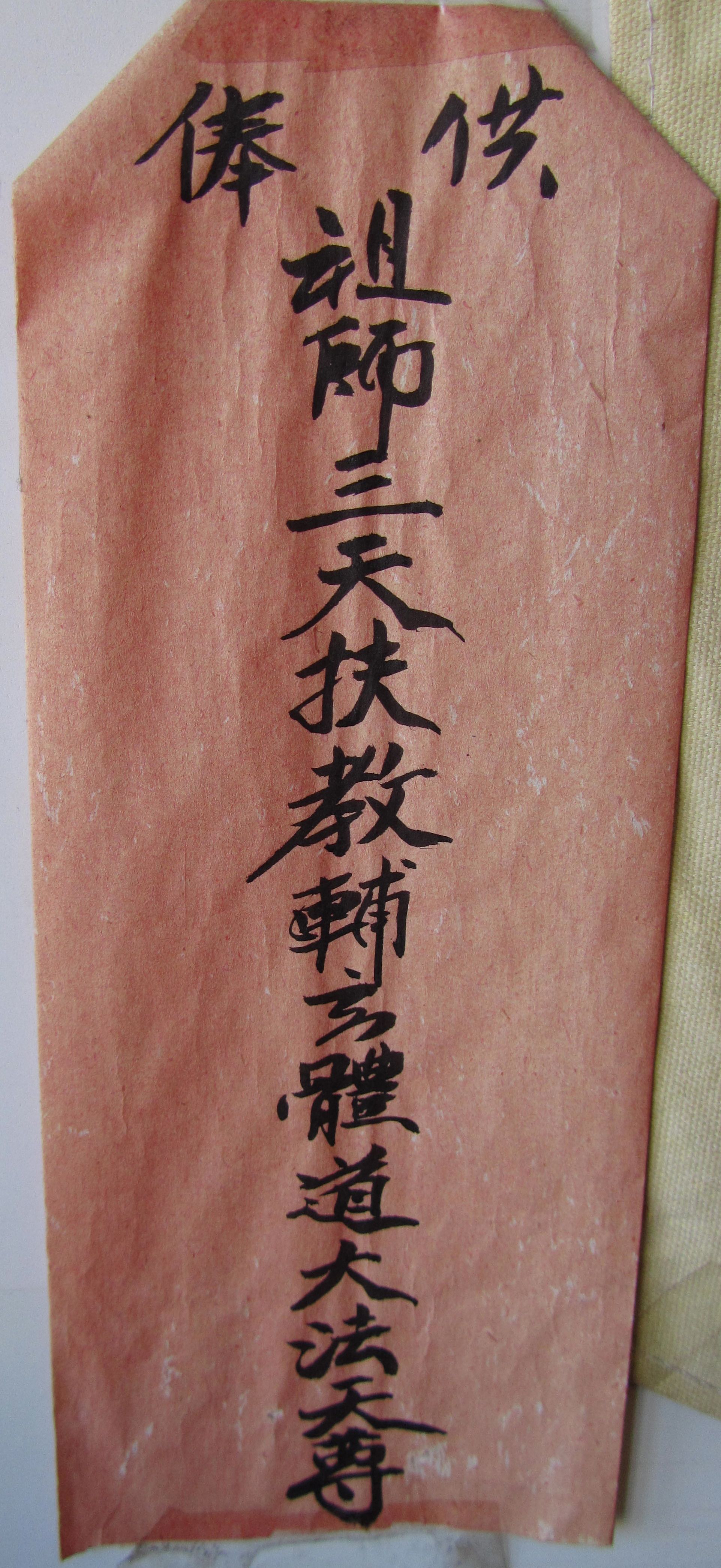

Detail: Hee Sing.

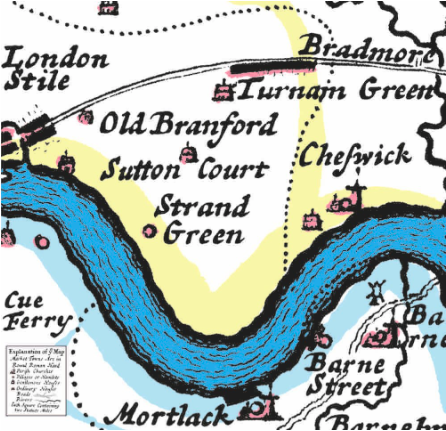

Also part of the Great Exhibition was a Chinese junk moored on the Thames—occasion for the curious case of the “fake Chinese mandarin” Hee Sing, who appears in a painting depicting the retinue of the royal family. In Berlioz’s Les soirées de l’orchestre (21st evening, including a variant of the above) he was even more underwhelmed by the soirées musicales et dansantes given onboard by the sailors:

Maintenant écoutez, messieurs, la description des soirées musicales et dansantes que donnent les matelots chinois sur la jonque qu’ils ont amenée dans la Tamise; et croyez-moi si vous le pouvez.

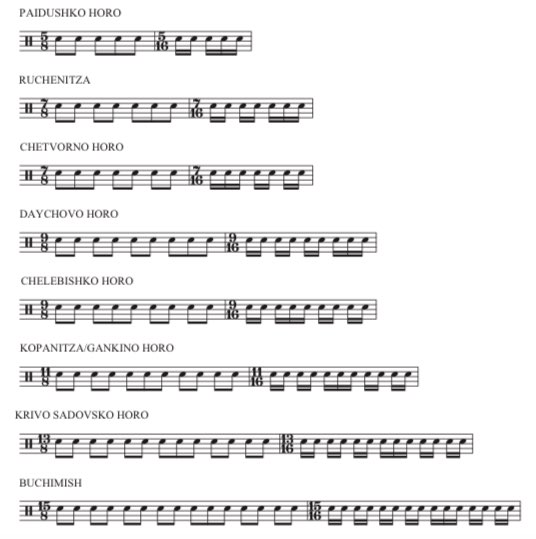

Ici, après le premier mouvement d’horreur dont on ne peut se défendre, l’hilarité vous gagne, et il faut rire, mais rire à se tordre, à en perdre le sens. J’ai vu les dames anglaises finir par tomber pâmées sur le pont du navire céleste ; telle est la force irrésistible de cet art oriental. L’orchestre se compose d’un grand tam-tam, d’un petit tam-tam, d’une paire de cymbales, d’une espèce de calotte de bois ou de grande sébile placée sur un trépied et que l’on frappe avec deux baguettes, d’un instrument à vent assez semblable à une noix de coco, dans lequel on souffle tout simplement, et qui fait : Hou ! hou ! en hurlant ; et enfin d’un violon chinois. Mais quel violon ! C’est un tube de gros bambou long de six pouces, dans lequel est planté une tige de bois très-mince et long d’un pied et demi à peu près, de manière à figurer assez bien un marteau creux dont le manche serait fiché près de la tête du maillet au lieu de l’être au milieu de sa masse. Deux fines cordes de soie sont tendues, n’importe comment, du bout supérieur du manche à la tête du maillet. Entre ces deux cordes, légèrement tordues l’une sur l’autre, passent les crins d’un fabuleux archet qui est ainsi forcé, quand on le pousse ou le tire, de faire vibrer les deux cordes à la fois [sic]. Ces deux cordes sont discordantes entre elles, et le son qui en résulte est affreux. Néanmoins, le Paganini chinois, avec un sérieux digne du succès qu’il obtient, tenant son instrument appuyé sur le genou, emploie les doigts de la main gauche sur le haut de la double corde à en varier les intonations, ainsi que cela se pratique pour jouer du violoncelle, mais sans observer toutefois aucune division relative aux tons, demi-tons, ou à quelque intervalle que ce soit. Il produit ainsi une série continue de grincements, de miaulements faibles, qui donnent l’idée des vagissements de l’enfant nouveau-né d’une goule et d’un vampire.

Dans les tutti, le charivari des tam-tams, des cymbales, du violon et de la noix de coco est plus ou moins furieux, selon que l’homme à la sébile (qui du reste ferait un excellent timbalier), accélère ou ralentit le roulement de ses baguettes sur la calotte de bois. Quelquefois même, à un signe de ce virtuose remplissant à la fois les fonctions de chef d’orchestre, de timbalier et de chanteur, l’orchestre s’arrête un instant, et, après un court silence, frappe bien d’aplomb un seul coup. Le violon seul vagit toujours. Le chant passe successivement du chef d’orchestre à l’un de ses musiciens, en forme de dialogue; ces deux hommes employant la voix de tête, entremêlée de quelques notes de la voix de poitrine ou plutôt de la voix d’estomac, semblent réciter quelque légende célèbre de leur pays. Peut-être chantent-ils un hymne à leur dieu Bouddah, d’ont la statue aux quatorze bras orne l’intérieur de la grand’chambre du navire.

Je n’essaierai pas de vous dépeindre ces cris de chacal, ces râles d’agonisant, ces gloussements de dindon, au milieu lesquels malgré mon extrême attention, il ne m’a été possible de découvrir que quatre notes appréciables (ré, mi, si, sol). Je dirai seulement qu’il faut reconnaître la supériorité de la small-footed Lady et de son maître de musique. Evidemment les chanteurs de la maison chinoise sont des artistes, et ceux de la jonque ne sont que des mauvais amateurs. Quant à la danse de ces hommes étranges, elle est digne de leur musique. Jamais d’aussi hideuses contorsions n’avaient frappé mes regards. On croit voir une troupe de diables se tordant, grimaçant, bondissant, au sifflement de tous les reptiles, au mugissement de tous les monstres, au fracas métallique de tous les tridents et de toutes les chaudières de l’enfer… On me persuadera difficilement que le peuple chinois ne soit pas fou…

[For a fine English version, see Berlioz, translated Barzun, Evenings with the orchestra (Chicago, 1956/1999 edition), pp.246–250.]

Here the Illustrated London News acquits itself no better:

At the evening performance the queer old craft is lighted up with festoons of coloured lamps—a sort of miniature [missing] hall, and in the midst stands an open orchestra, in which four or five instrumentalists (“barbarians,” not Chinese) prepare the ear for the extraordinary combination of sounds which is to follow. Nothing can exceed the gravity of the “celestials,” as they take their position in the midst of the assembly on the main-deck, and proceed to fright the ear with gong and drum, and cymbal and agonizing cat-gut: the leader beating time with a stake upon a sort of tin saucepan-lid supported on three legs. Then the vocalization! The extraordinary squeaking duet, half plaintive, half comic, between the said leader (who is a sort of Costa and Mario rolled into one) and a younger aspirant in the background—what can possibly exceed its harrowing and ludicrous effect? Nothing except that impromptu feline discourse which we sometimes hear on house-tops at the dead of night.

The concert being concluded amidst the breathless silence of an astonished auditory, the war demonstrations and feats of arms then commence and these are certainly no less extraordinary than what has gone before. The first set consists of a set of grotesque posturing, in which the performers disport themselves severely one after the other, each succeeding one striving to outdo the other in the wildness and extravagance of his gesture—flying and leaping round the deck, thrusting out the arms right and left, threatening, retreating, &c. the musicians all the time keep up a terrific clang.

Next come a series of somewhat similar performances with long poles or lances, this scene closing with a set-to between two performers, which we have endeavored to embody in our engraving. Swords are also introduced and brandished about in the same manner, which, if intended to give any idea of the military science of the Chinese, shows them to be very far behind any other known nation in the world in that respect. One young hero, in the course of his “war demonstrations,” afforded great amusement every now and then, particularly after some very startling efforts at cut and thrust, by throwing himself down, and turning a somersault over his shield. When we left, the “barbarian” orchestra was about to strike up again, and dancing, it was said, was about to commence, but we did not wait for it.

For a recent French recreation, see here. Indeed, both the family and the junk had already appeared for P.T. Barnum’s Chinese museum: see Krystyn R. Moon, Yellowface: creating the Chinese in American popular music and performance, 1850s–1920s (2005), pp.62–6. For another portrait of the family, see here.

Hector’s Napoleon impression always brought the house down.

Among composers, a broader view of musicking worldwide would have to wait for figures such as Debussy and Bartók. Still, even today views like those of Berlioz remain far from obsolete. So much for music as a universal language.

* * *

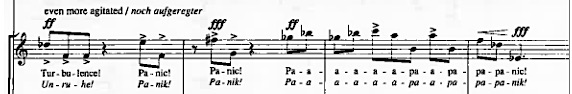

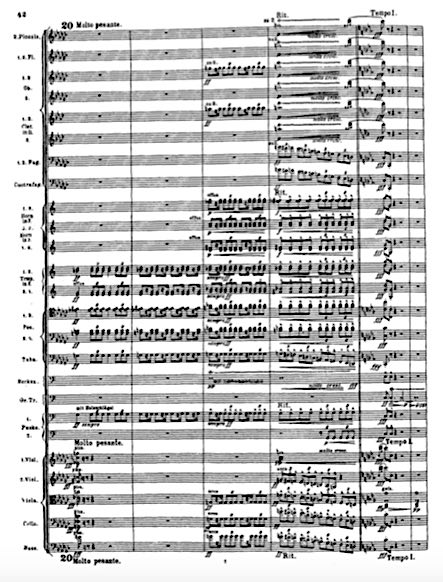

Ironically, in reviews by Berlioz’s contemporaries of his own new works he was hoist on his own petard—using rather similar vocabulary, as if taking revenge on behalf of the Chinese. Here are just a few among an embarras de richesse, cited in Slominsky‘s wonderful Lexicon of musical invective, pp.57–61:

His rare melodies are deprived of meter and rhythm; and his harmony, a bizare assemblage of sounds, not easily blended, does not always merit the name. I believe that what M. Berlioz writes does not belong to the art which I cusomarily regard as music, and I have the complete certainty that he lacks the prerequisites of this art.

Berlioz, musically speaking, is a lunatic; a classical composer only in Paris, the great city of quacks. His music is simply and undisguisedly nonsense.

M. Berlioz is utterly incapable of producing a complete phrase of any kind. When, on rare occasions, some glimpse of a tiune makes its appearance, it is cut off at the edges and twisted about in so unusual and unnatural a fashion as to give one the idea of a mangled and mutilated body, rather than a thing of fair proportions. Moreover, the little tune that seems to exist in M. Berlioz is of so decidely vulgar a character as to exclude the possibility of our supposing him possessed of a shadow of feeling.

I can compare Le Carneval romain by Berlioz to nothing but the caperings and gibberings of a big baboon, over-excited by a dose of alcoholic stimulus.

Dragging the icon to the trash, eh. For astounding Saint-Saëns on the violon chinois, click here.

See also Berlioz: a love scene. For Berlioz’s prophetic word-painting of a 1960s’ curry-house menu, cliquez ici; and for his evocation of furniture removal, ici. For Mahler’s vision of the mystic East, see here; and for Cantonese music in post-war London, here.

As to Arsenal’s young star, I’m keen to get this headline in early:

As to Arsenal’s young star, I’m keen to get this headline in early: