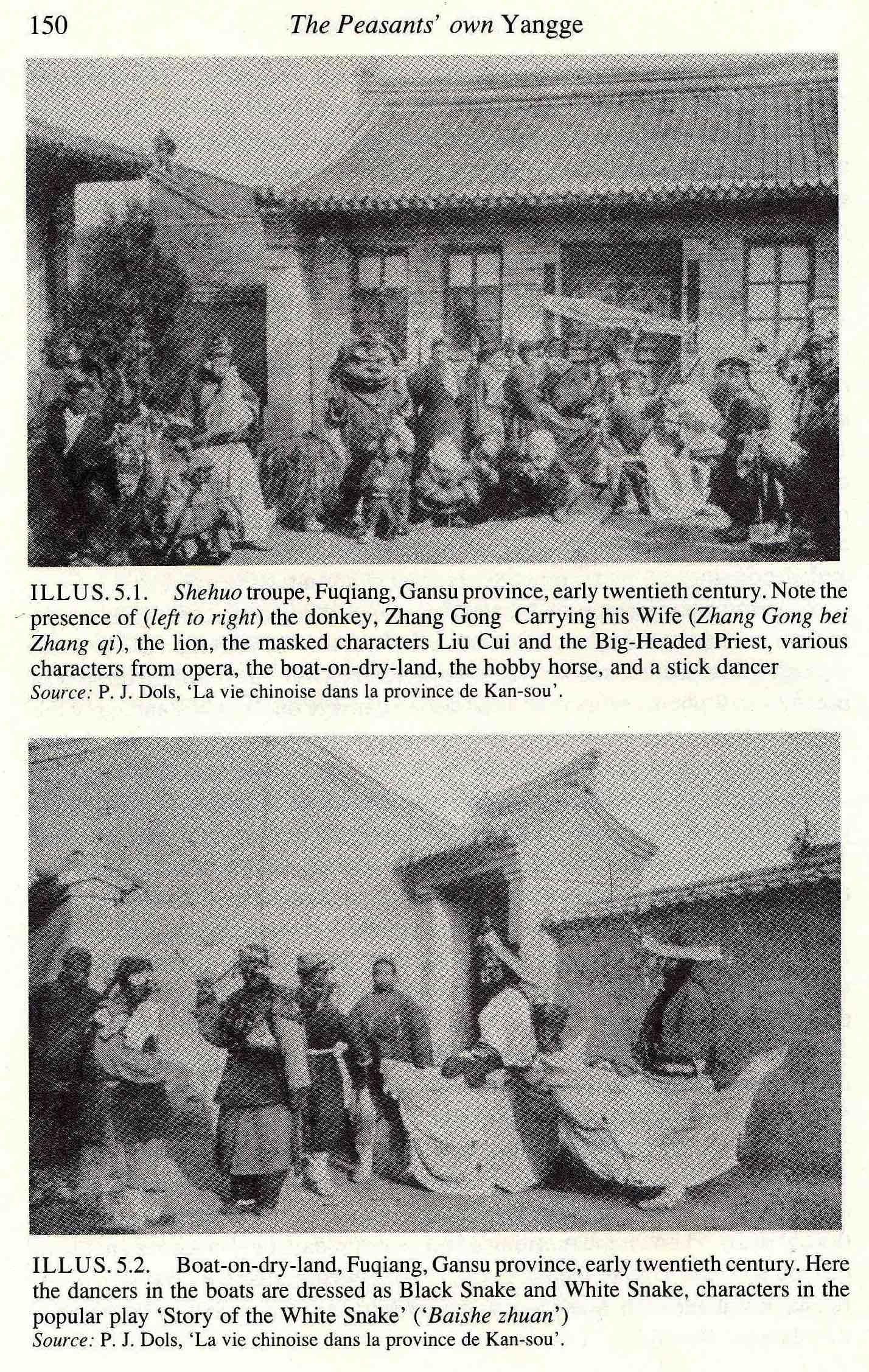

Hand-in-hand with my focus on ritual and expressive culture, I have long been concerned to document life-stories—of ordinary people, artists, and scholars, both in China (cf. my detailed work on the Gaoluo villagers and the Li family Daoists) and Europe.

Under the Iron curtain tag (see also roundup here) I’ve broached life-stories under state socialism in the GDR (here and here), Czechoslovakia, and Ukraine (blind minstrels, and the famine)—and tribulations under the Soviet regime were the context for this post on ethnic minorities there. But now, reading

- Orlando Figes, The whisperers: private lives in Stalin’s Russia (2007)

makes an accessible single-volume study to begin shedding light on my ignorance of ordinary lives in the Soviet Union. Apart from the importance of the topic in itself, I muse (as ever) on the similarities and differences with Maoist—and post-Maoist—China.

Many books describe the externals of the Terror—the arrests and trials, enslavements and killings of the Gulag—but The whisperers is the first to explore in depth its influence on personal and family life.

The oral history of family memory makes a counterweight to the official narrative (notes also Soviet lives at war). Figes interrogates the issues in interpreting such sources. His website, following on from his oral history project, is a treasury of related material. For significant caveats on the book, see here (with further links).

As the regime sought to erase the distinction between public and private life, Figes describes both the effectiveness of the Soviet indoctrination of children and the internal conflict with messages they gleaned from their families. The system taught dissimulation, producing duplicity and lifelong fear. As a survival strategy, people learned to wear a mask, going into “internal emigration”, leading double lives; they had to adjust to the system merely in order to survive. They learned not to talk: “whisperers” were both those who whispered out of fear of being overheard, and those who informed.

Figes details the effects of successive waves of repression, before, during, and after the Stalin regime from 1928 to 1953, interweaving many family histories throughout the book. The case of its central figure Konstantin Simonov, who “embodied all the moral conflicts and dilemmas of his generation”, though revealing in its complexity, is exceptional in his high profile as cultural cadre. The index, and the website, can be used to follow the stories of individual families throughout the book. The cast includes both cadres and the catch-all of “kulaks”, but seems more urban than rural—whereas China was more predominantly rural as late as the 1970s. Even early images of “kulaks” being expelled, and photos from the gulag (however manufactured), suggest that China was still more backward—and repressed—in the 1950s than Russia in the 1920s.

Exiles in a “special settlement” in western Siberia, 1933.

Exiles in a “special settlement” in western Siberia, 1933.

For Maoist China too, diverse sources can be assembled to modify and counter the official narrative, including memoirs, family photos and documents, local archives, and so on—note Sebastian Veg, Popular memories of the Mao era. Memoirs and biographical accounts have proliferated since the liberalizations of the 1980s. In film, recent projects such as laogai documentaries and Wu Wenguang’s Caochangdi Work Station are impressive. Also revealing are fictional portrayals—not just laogai novelists like Zhang Xianliang and Yan Lianke, but films such as The blue kite that suggest the everyday tribulations of ordinary families. But while there may be a comparable wealth of material for China, it’s hard to envisage such an accessible, personal, wide-ranging and diachronic account as The whisperers.

Illuminating his sources perceptively, Figes identifies clear periods in people’s fates under the Soviet regime. The repression took place over a longer period than that of Maoism, and may seem to have been even more terrifying. The gulag—among the extensive literature on which, see e.g. Anne Applebaum, Gulag: a history (2003)—looms larger in the public (and private) image of the USSR than the laogai system in China, although the latter has also become the subject of brave research. Executions, and the all-pervading NKVD, also seem to play a more common role in Soviet history.

Below I can only list some of the main themes of the book, rather than citing the many personal life-stories that illustrate them—which is actually its outstanding strength.

* * *

Figes opens with Children of 1917, on the early years of the revolution, and the beginnings of state indoctrination and the war on religion. In 1926 the peasantry represented 82% of the Soviet population—cf. China, where the rural population peaked at 84% in 1963. But urban populations grew rapidly. Families were dislocated; millions of children were abandoned, having to fend for themselves. Figes describes life at the camps. Some “kulaks” managed to flee from the camps, living on the run.

Young people renounced their relatives, for various motives.

As millions of people left their homes, changed their jobs, or moved around the country, it was relatively easy to change or reinvent one’s social class. People learned to fashion for themselves a class identity that would help them advance. They became clever at concealing or disguising impure social origins, and at dressing up their own biographies to make them seem more “proletarian”.

But they were haunted by the constant threat of exposure—many concealed their secrets right until the 1990s.

In The great break (1928–32) Figes describes the temporary relaxation in the assault against religion between 1924 and 1928:

On 2 August 1930, the villagers of Obukhovo celebrated Ilin Day, an old religious holiday to mark the end of the high summer when Russian peasants held a feast and said their prayers for a good harvest. After a service in the church, the villagers assembled at the Golovins, the biggest family in Obukhovo, where they were given home-made pies and beer inside the house while their children played outside. As evening approached, the village dance (gulian’e) began. Led by a band of balalaika players and accordionists, two separate rows of boys and girls, dressed in festive cottons, set off from the house, singing as they danced down the village street.

Thereafter, while clandestine belief may have persisted, I find rather few clues to any public religious (or even customary) activity—by contrast with Maoist China, where it kept resurfacing despite constant campaigns. Am I wrong to see local Chinese populations as more resilient in maintaining their expressive culture under Maoism? Still in Obukhovo:

That year the holiday was overshadowed by violent arguments. The villagers were bitterly divided about whether they should form a collective farm (kolkhoz), as they had been ordered by the Soviet government. […] There were terrifying tales of soldiers forcing peasants into the kolkhoz, of mass arrests and deportations, of houses being burned and people killed, and of peasants fleeing from their villages and slaughtering their cattle to avoid collectivization.

“Kulaks” exiled from the village of Udachne, Khryshyne (Ukraine), early 1930s.

“Kulaks” exiled from the village of Udachne, Khryshyne (Ukraine), early 1930s.

As Figes explains:

During just the first two months of 1930, half the Soviet peasantry (about 60 million people in over 100,000 villages) was herded into the collective farms. […] Peasants who spoke out against collectivization were beaten, tortured, threatened, and harassed, until they agreed to join the collective farm. Many were expelled as “kulaks” from their homes and driven out of the village. The herding of the peasants into the collective farms was accompanied by a violent assault against the Church, the focal point of the old way of life of the village, which was regarded by the Bolsheviks as a source of potential opposition to collectivization. Thousands of priests were arrested and churches were looted and destroyed, forcing millions of believers to maintain their faith in the secrecy of their own homes. […]

There was surprisingly little peasant opposition to the persecution of the “kulaks”. […] The majority of the peasantry reacted to the sudden disappearance of their fellow villagers with passive resignation born of fear.

Yevdokiia and Nikolai with their son Aleksei Golovin (1940s).

Yevdokiia and Nikolai with their son Aleksei Golovin (1940s).

In Obukhovo the Golovins were deported on 4th May 1930:

I recall the faces of the people standing there. They were our friends and neighbours—the people I had grown up with. No-one approached us. No-one said farewell. They stood there silently, like soldiers in a line. They were afraid.

Still,

There was widespread resistance to collectivization, even though most villagers acquiesced in the repression of “kulaks”. In 1929–30, the police registered 44,779 “serious disturbances”. Communists and rural activists were killed in their hundreds, and thousands more attacked. There were peasant demonstrations and riots, assaults against Soviet institutions, acts of arson and attacks on kolkhoz property, protests against closures of churches.

Figes unpacks the motives of those responsible for enforcing the brutal war against the peasantry.

Under The pursuit of happiness (1932–36), while observing brief concessions to consumer culture (promoting perfume, cosmetics, fun), he evokes urban projects like the construction of the Moscow metro from 1932, using peasant immigrants and gulag prisoners:

The splendour of these proletarian palaces, which stood in such stark contrast to the cramped and squalid private spaces in which the majority of people lived, played an important moral role (not unlike the role played by the Church in earlier states).

But popular unrest continued. The rise of a new bureaucratic elite also caused discontent:

In 1932, a manager at Transmashtekh, a vast industrial conglomerate, wrote to the Soviet President Mikhail Kalinin:

The problem with Soviet power is the fact that it gives rise to the vilest type of official—one that scrupulously carries out the general designs of the supreme authority… This official never tells the truth, because he doesn’t want to distress the leadership. He gloats about famine and pestilence in the district or ward controlled by his rival. He won’t lift a finger to help his neighbour… All I see around me is loathsome politicizing, dirty tricks, and people being destroyed for slips of the tongue. There’s no end to the denunciations. You can’t spit without hitting some revolting denouncer or liar. What have we come to? It’s impossible to breathe. The less gifted a bastard, the meaner his slander. Of course the purge of your Party is none of my business, but I think that as a result of it, decent elements still remaining will be cleaned out.

Figes notes the “hierarchy of poverty”. And meanwhile the lives of women failed to improve:

For women nothing changed in the 1930s—they worked long hours at a factory and then did a second shift at home, cooking, cleaning, caring for the children on average for five hours every night—whereas men were liberated from most of their traditional domestic duties (chopping wood, carrying water, preparing the stove) by the modernization of workers’ housing, which increased the provision of running water, gas, and electricity, leaving them more time for cultural pursuits and politics.

Trotsky had trenchant views on sexual politics:

One of the dramatic chapters in the great book of the Soviets will be the tale of the disintegration and breaking up of those Soviet families where the husband as a Party member, trade unionist, military commander or administrator, grew and developed and acquired new tastes in life, and the wife, crushed by the family, remained on the old level. The road of the two generations of Soviet bureaucracy is sown thick with the tragedies of wives rejected and left behind. The same phenomenon is now to be observed in the new generation. The greatest of all crudities and cruelties are to be met perhaps in the very heights of the bureaucracy, where a very large percentage are parvenus of little culture, who consider that everything is permitted to them. Archives and memoirs will some day expose downright crimes in relation to wives, and to women in general, on the part of those evangelists of family morals and the compulsory “joys of motherhood”, who are, owing to their position, immune from prosecution.

Figes documents the constrained domestic spaces of urban dwellers, and the tensions caused by lack of privacy, with some fine room plans.

Above, left: Khaneyevsky household, Moscow; right: Reifshnieders’ room, Moscow.

Below, left: Nikitin and Turkin apartments, Perm; right: Bushuev “corner” room, Perm.

In later years many people felt a rose-tinted nostalgia for the pre-war years, when

Everybody helped one another, and there were no arguments. No-one was stingy with their money—they spent their wages as soon as they were paid. It was fun to live then. Not like after the war, when people kept their money to themselves, and closed their doors.

But, as in China (where many peasants felt an equally perplexing nostalgia for the commune system), there’s ample evidence for the contrary view of communal life:

It was a different feeling of repression from arrest, imprisonment, and exile, which I’ve also experienced, but in some ways it was worse. In exile one preserved a sense of one’s self, but the repression I felt in the communal apartment was the repression of my inner freedom and individuality. I felt this repression, this need for self-control, every time I went into the kitchen, where I was always scrutinized by the little crowd that gathered there. It was impossible to be oneself.

Still, millions of people were taught to believe that

hard work today would be rewarded tomorrow, when the “good life” would be enjoyed by all.

Though the mid-1930s have been regarded as the calm before the storm,

for millions of people whose families were scattered in the Gulag’s labour camps and colonies, these years were as bad as any other.

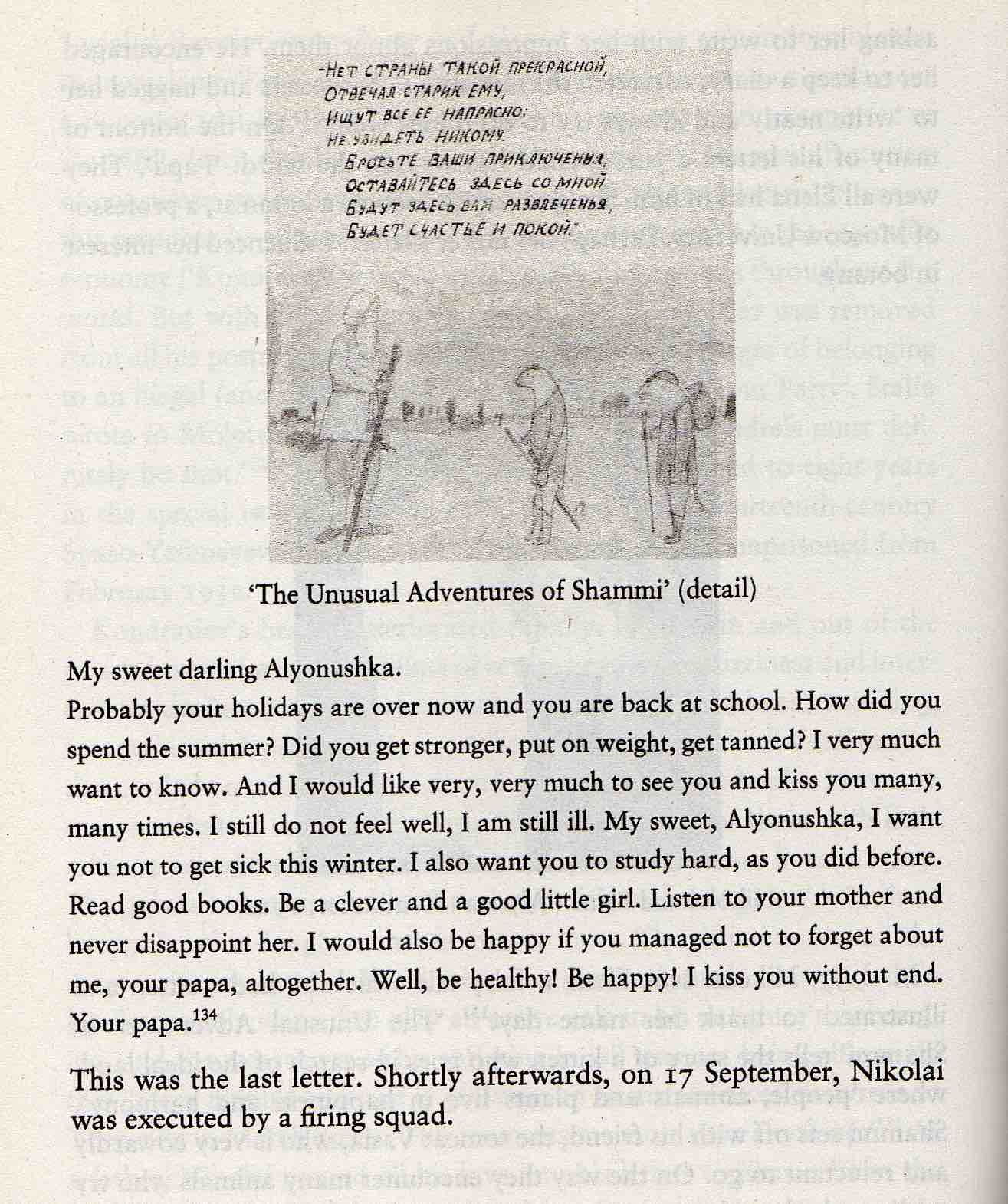

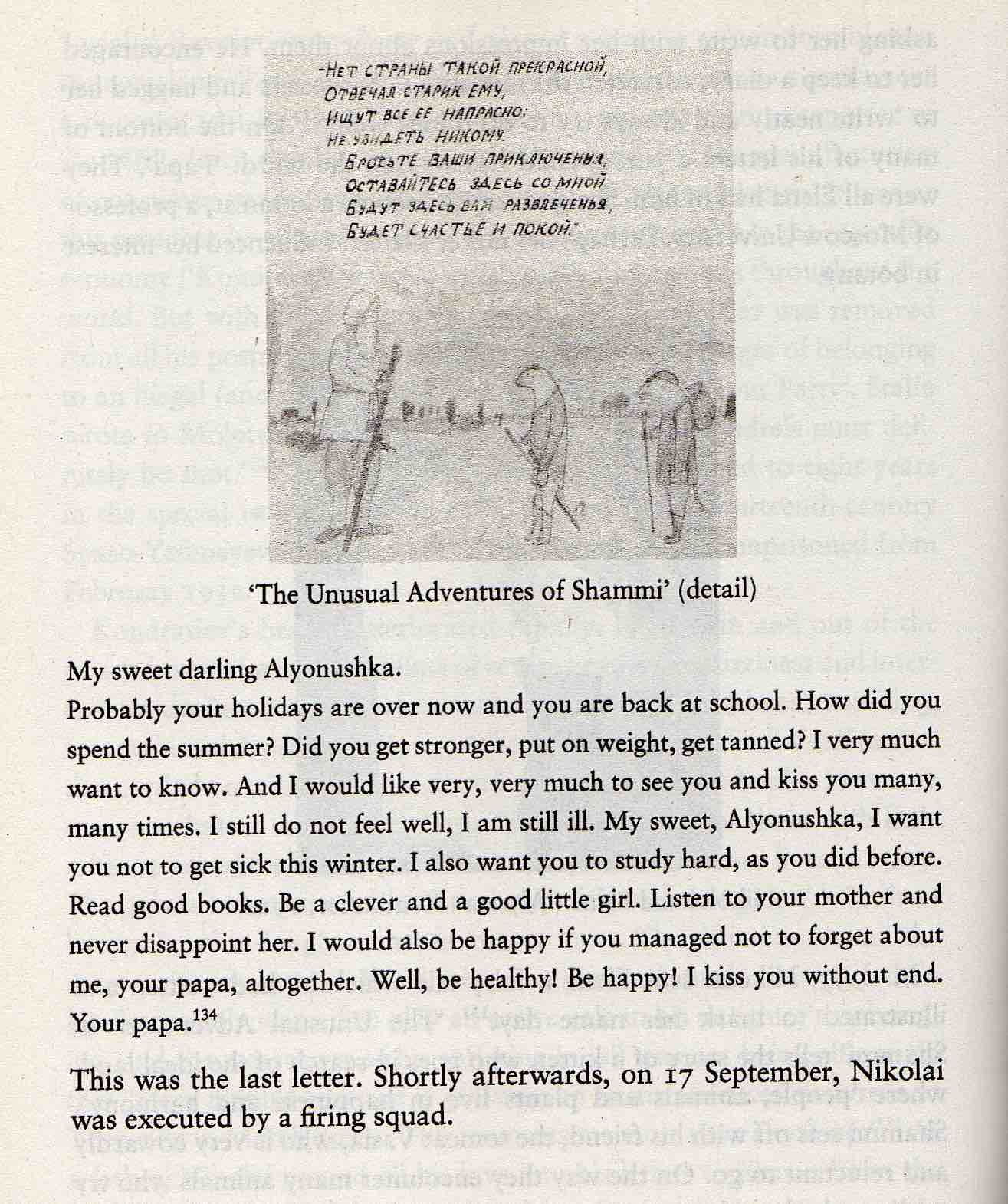

Nikolai Kondratiev’s last letter to his daughter, 1938.

Nikolai Kondratiev’s last letter to his daughter, 1938.

In The great fear (1937–38), Figes explains that the Terror was not a routine wave of mass arrest, but a calculated policy of mass murder. Among the complex reasons prompting Stalin’s purge was the imminent threat of war. Not just the direct “offenders” but also their kin were hunted down. The motives of the informers, often themselves under extreme pressure, were also complex.

In 1938, the NKVD chief Yezhov was deposed. “The real reason for Yezhov’s fall was Stalin’s growing sense that mass arrests were no longer a workable strategy. At the rate the arrests were going, it would not be long before the entire Soviet population was in jail.” Under his successor Beria the purge was scaled down.

Fear brought out the worst in people. Yet there was also acts of extraordinary kindness by colleagues, friends, and neighbours, sometimes even strangers, who took enormous risks to help the families of “enemies of the people”. […]

The disappearance of a father and a husband placed enormous strain on families. Wives renounced husbands who had been arrested, not necessarily because they thought their spouses might be “enemies of the people”, although they may have had that thought, but because it made survival easier and gave protection to their families (many husbands for this reason advised wives to renounce them). […] It took extraordinary resilience, and not a little bravery, for women to resist these pressures and stand by their husbands.

There is scant consolation in Remnants of terror (1938–41) on the eve of the German invasion. Figes praises the untold acts of heroism of grandmothers striving to keep together the scattered remains of repressed families.

Elena Lebedeva with her granddaughters, Natalia (left) and Elena Konstantinova,

Elena Lebedeva with her granddaughters, Natalia (left) and Elena Konstantinova,

Ak-Bulak, 1940.

But many children ended up in orphanages, roamed the streets begging, joined street gangs, or were themselves sent to children’s labour colonies.

Meanwhile, in a Nazi–Soviet pact that alarmed faithful Communists, both Germany and the Red Army invaded Poland, and the USSR pressurized the Baltic states to accept pacts of “defence and mutual assistance”, extending the reach of their reign of terror.

The theme of Wait for me (1941–45) is the social consequences of the sudden German invasion of the USSR in 1941. Apart from its global significance, it was also crucial for the maintenance of the Soviet regime. Stalin now had no choice but to call for unity, setting aside class struggle and ideology. Many saw that the whole climate of the Terror had played a major role in the USSR’s initial inability to resist the invasion; criticism became open (some even welcomed the prospect of a German victory), and arrests continued.

But the desperate need for self-defence did indeed foster a spirit of national unity. The horrors of war against a brutal external enemy helped people forget, for now, the misery of their situation during “peacetime”. Patriotic morale even produced a new merging of the public sphere and the intimate world of personal relationships.

As the tide turned, the Red Army chased the Germans back. Convinced by the courageous determination of the Soviet forces, Figes seeks to explain it. Terror and coercion played a role, but

Appeals to the patriotism of the Soviet people were more successful. The vast majority of Soviet soldiers were peasant sons; their loyalty was not to Stalin or the Party, which had brought ruin to the countryside, but to their homes and families, to their own vision of the “motherland”.

The image of Mother Russia was promoted; controls over religion were temporarily relaxed. Hatred of the enemy was also an important element. But most significant, Figes suggests, was the cult of personal sacrifice:

As Simonov remarked, the people were prepared for the privations of the war—the sharp decline in living standards, the breaking up of families, the disruption of ordinary life—because they had already been through much the same in the name of the Five Year Plans.

Still,

Contrary to the Soviet myth of wartime national unity, Soviet society was more fractured during the war than at any previous time since the Civil War. Ethnic divisions had been exacerbated by the Soviet state, which scapegoated certain national minorities, such as the Crimean Tatars, the Chechens, and the Volga Germans, and exiled them to regions where they were not welcomed by the local populace. Anti-Semitism, which had been largely dormant in Soviet society before the war, now became widespread. It flourished especially in areas occupied by Hitler’s troops, where a large section of the Soviet population was directly influenced by the Nazis’ racist propaganda, but similar ideas were imported to places as remote as Kazakhstan, Central Asia, and Siberia by Soviet soldiers and evacuees from the western regions near the front.

Even so, people united for the defence of their local communities. And soldiers found camaraderie:

Veterans recall the intimacy of these wartime friendships with idealism and nostalgia. They claim that people then had “bigger hearts” and “acted from the soul”, and that they themselves were somehow “better human beings”, as if the comradeship of the small collective unit was a cleaner sphere of ethical relationships and principles than the Communist system, with all its compromises and contingencies. They often talk as if they found in the collectivism of these groups of fellow soldiers a type of “family” that was missing from the lives before the war (and would be missing afterwards).

Left: Zinaida Bushueva with her brothers, 1936.

Left: Zinaida Bushueva with her brothers, 1936.

Right: Zinaida (centre) in ALZhIR, 1942. A rare private photograph of Gulag prisoners, it was taken to send to relatives. The three women were photographed together to reduce the costs.

During the war the exploitation of the Gulag labour force intensified—in 1942 one in four Gulag workers died.

As Pasternak would write in the epilogue of Doctor Zhivago (1957), “When the war broke out, its menace of real death, were a blessing compared to the inhuman power of the lie, a relief because it broke the spell of the dead letter.” The relief was palpable. People were allowed to act in ways that would have been unthinkable before the war. By necessity, they were thrown back on their own initiative—they spoke to one another and helped each other without thinking of the political dangers to themselves, and from this spontaneous activity a new sense of nationhood emerged. The war years, for this reason, would come to be recalled with nostalgia.

The years 1941 to 1943 were described as a period of “spontaneous de-Stalinization”. People were empowered to think critically; a new freedom of expression even included political debate. The revival of religious activity continued through to 1948. Still, over the whole period cultural and religious life at a distance from urban centres remains somewhat obscure.

All this marked the beginning of a fundamental change of values. Towards the end of the war, as the Red Army entered Europe, their encounter with conditions there—clearly superior even amidst its desperately ravaged state, to which indeed they contributed further—also allowed them to question Soviet propaganda. And like the British, their experiences gave them ideals of building a better society—in their case, dismantling the collective farms, establishing democracy and religious freedoms. “Party leaders were understandably anxious about the return of all these men with their reformist ideas.” Such liberal notions were anyway spreading among civilians, not least as a result of the alliance with Britain and the USA.

As Ilia Ehrenburg wrote,

Everybody expected that once victory had been won, people would know real happiness. We realized, of course, that the country had been devastated, impoverished, that we would have to work hard, and we did not have fantasies about mountains of gold. But we believed that victory would bring justice, that human dignity would triumph.

Their hopes were soon dashed.

The ending of the war coincided with the first mass release of prisoners from the Gulag. […] Families began to piece themselves together again. Women took the lead in this recovery, sometimes travelling across the country in search of husbands and children. There were tight restrictions on where former prisoners could live. Most of them were banned from residing in the major towns. So families who wanted to be together often had to move to remote corners of the Soviet Union. Sometimes the only place they could find to settle was in the Gulag zone.

But the Gulag population actually expanded in the years after the war, with forced labour making a significant element in the economy.

People were damaged; fear, and silence, still reigned. All this also makes even more remarkable the widespread telling of political jokes, throughout the whole period.

The post-war period is the subject of Ordinary Stalinists (1945–53).

No other country suffered more from the Second World War than the Soviet Union. According to the most reliable estimates, 26 million Soviet citizens lost their lives (two-thirds of them civilians) […] and 4 million disappeared between 1941 and 1945. […] The demographic consequences of the war were catastrophic. Soviet agriculture never really recovered from this demographic loss. The kolkhoz became a place for women, children, and old men.

The material devastation was grievous too. Another famine occurred from 1946 to 1948. The brief improvement in the supply of consumer goods before the war was a distant memory. With people no longer afraid to express their discontent, strikes and demonstrations broke out. But as the new threat posed by the Cold War developed, Stalin moved promptly to purge the army and Party leadership, and to rule out any idea of political reform. Censorship was tightened; the new wave of dissent had to continue underground.

Left: Inna Gaister (aged 13) with her sisters Valeriia (3) and Natalia (8), Moscow, 1939. The photograph was taken to send to their mother in the Akmolinsk labour camp (ALZhIR).

Right: Inna Gaister (centre) with two friends at Moscow University, 1947.

But a new type of middle class now emerged, better educated and less ideological in outlook—though they had to conform, at least outwardly, to the demands of the regime, perfecting the art of wearing masks. Figes gives more stories of informants. Valentina Kropotina made her whole career by informing. With her “kulak” background,

I was basically a street-child, dressed in rags, barefoot… All my childhood memories are dominated by the feeling of hunger… I was afraid of hunger, and even more, of poverty. And I was corrupted by this fear.

She felt no remorse for what she did. Still,

The “little terror” of the post-war years was very different from the Great Terror of 1937–8. It took place, not against the backdrop of apocalypse, when frightened people agreed to betrayals and denunciations in the desperate struggle to save their lives and families, but against the background of a relatively mundane and stable existence, when fear no longer deprived people of their moral sensibility.

Anti-Semitism, always latent, escalated along with the “anti-cosmopolitan” campaign. When Stalin died in 1953, even some victims of the Terror felt genuine sorrow, but

The mourning ceremonies in Krasnodar were more like a holiday. They put on a mournful face, but there was a sparkle in their eyes, the hint of a smile beneath their greeting, that made it clear that they were pleased.

Even so, there was still no release from fear—indeed, people were anxious for the future. Beria played a role in allaying such fears, though he was soon executed in a Kremlin coup organized by Kruschev. Hopes were high among Gulag inmates; new demonstrations broke out, which helped bring about the abolition of the system. About 40% of the gulag population were released in an amnesty on 27th March 1953—though they returned to their families physically and mentally broken. The climate in the Soviet Union also led to the serious demonstrations that erupted in the GDR.

The story continues in Return (1953–56).

The family emerged from the years of terror as the one stable institution in a society where virtually all the mainstays of human existence—the neighbourhood community, the village and the church—had been weakened or destroyed. For many people the family represented the only relationship they could trust, the only place they felt a sense of belonging, and they went to extraordinary lengths to reunite with relatives.

But former prisoners found it hard to build relationships, to find jobs and places to live. They still had to confront those who had betrayed them, although they also understood the extreme pressures that had led them to do so. The process of rehabilitation was laborious. And millions never returned from the camps.

Kruschev’s denunciation of Stalin in 1956 made a decisive break, the beginnings of the reformist thaw. Still, Stalin, rather than the whole system, was the scapegoat. But it also had consequences for the countries of east Europe, notably with the Hungarian uprising that year.

And just as the worst was over in the USSR, China systematically repeated its deadly mistakes. Dikötter outlines many of the same features of life under Maoism, but his treatment is less personal.

As Figes describes in the final chapter, Memory (1956–2006), even after 1956, the vast majority of ordinary people were still too cowed and frightened by the memory of the Stalinist regime to speak out openly. The thaw ended when Brezhnev replaced Kruschev in 1964; as dissidents were persecuted, people again suppressed their traumatic memories. Stoicism and passivity became enduring social norms.

But nostalgia for the war persisted, even overriding other assessments of the system. Viacheslav Kondratiev recalled:

For our generation the war was the most important event in our lives, the most important. This is what we think today. So we are not prepared to belittle in any way the great achievement of our people in those terrifying, difficult, and unforgettable years. The memory of our fallen soldiers is too sacred, our patriotic feelings are too pure and deep for that.

Eventually more candid memories of the war surfaced, such as the 1975 film A soldier went. A whole Gulag literature emerged.

Unlike the victims of the Nazi war against the Jews, for whom there could be no redeeming narrative, the victims of Stalinist repression had two main collective narratives in which to place their own life-stories and find some sort of meaning for their ordeals: the survival narrative, as told in the memoir literature of former Gulag prisoners, in which their suffering was transcended by the human spirit of the survivor; and the Soviet narrative, in which that suffering was redeemed by the Communist ideal, the winning of the Great Patriotic War, or the achievements of the Soviet Union.

Figes reflects on the startling paradox in the later myth of Norilsk,

a large industrial city built and populated by Gulag prisoners, whose civic pride is rooted in their own slave labour for the Stalinist regime,

as well as the popular nostalgia for Stalin (and again we might compare the Chinese nostalgia for Mao—see also here), which

reflects the uncertainty of their lives as pensioners, particularly since the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991; the rising prices that put many good beyond their means; the destruction of their savings by inflation; and the rampant criminality that frightened old people in their homes.

However,

nostalgia notwithstanding, the ruinous legacies of the Stalinist regime continued to be felt by the descendants of Stalin’s victims many decades after the dictator’s death. It was not only a question of lost relationships, damaged lives and families, but of traumas passed from one generation to the next. […]

Even in the last years of the Soviet regime, in the liberal climate of glasnost, the vast majority of Soviet families did not talk about their histories, or pass down stories of repression to their children. […] Fifteen years after the collapse of the regime, there are still people in the provinces who are afraid to talk about their past, even to their own children.

Again, the Chinese parallel is interesting: whereas the Soviet “liberation” occurred after over seventy years of repression, in China “reform and opening” not only happened earlier, following the collapse of Maoism in the late 1970s, but came after a mere thirty years of state repression. Both Russia and China suffered grievously under invasion and warfare; and for both, the hard-earned victory came to form a cornerstone of the national image. But whereas in China the war set the scene for the Communist takeover and the people finally “standing up”, in Russia it made an interlude within a system in which repression was already deeply entrenched; it seemed to offer hopes for reform, which were soon thwarted. In China too the lid on popular expression of trauma remained quite tightly sealed, though as Sebastian Veg notes, “after a period of post-traumatic outpour, followed by commodified nostalgia, popular memory in recent years has shown signs of moving towards more critical discussions.” But both Chinese and Russian regimes continue to devise new forms of repression.

* * *

In my post on Bloodlands (n.2) I mentioned attempts to compare death tolls under Hitler, Stalin, and Mao—in ascending order, it seems. As Timothy Snyder wrote,

it turns out that, with the exception of the war years, a very large majority of people who entered the Gulag left alive. Judging from the Soviet records we now have, the number of people who died in the Gulag between 1933 and 1945, while both Stalin and Hitler were in power, was on the order of a million, perhaps a bit more. The total figure for the entire Stalinist period is likely between two million and three million. The Great Terror and other shooting actions killed no more than a million people, probably a bit fewer. The largest human catastrophe of Stalinism was the famine of 1930–1933, in which more than five million people died.

But appalling are the death tolls, they are far from the whole story. Now that I read Figes’s account, it seems callous and irrelevant to dwell on such statistics.

With my classical, mystical background, it took me a long time to appreciate the importance of all this—and it may still elude younger people in the UK, Russia, and China. But having long focused on the life-stories of Chinese ritual specialists and their patrons, I continue to find such accounts an illuminating perspective on modern history, for China and elsewhere.

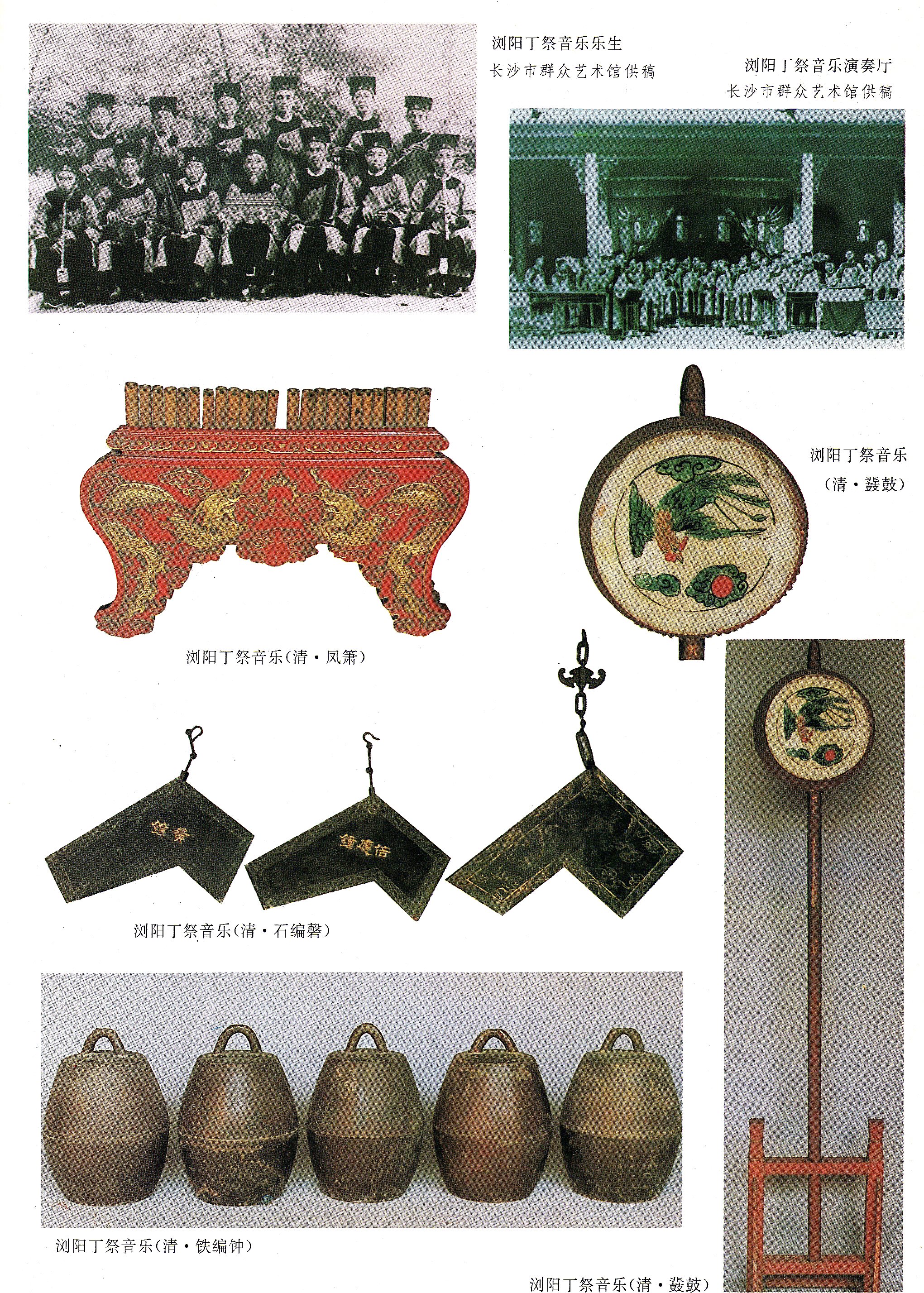

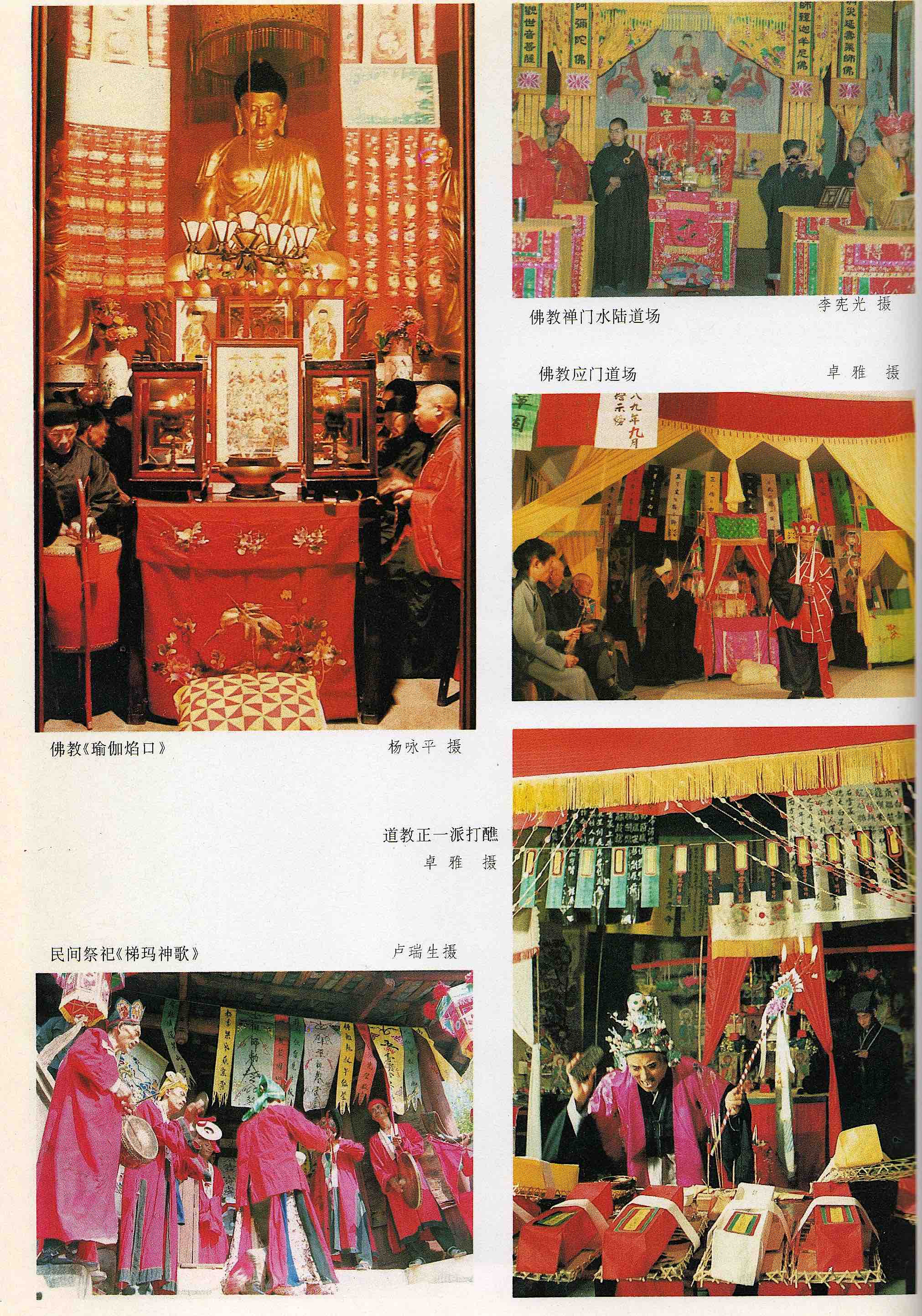

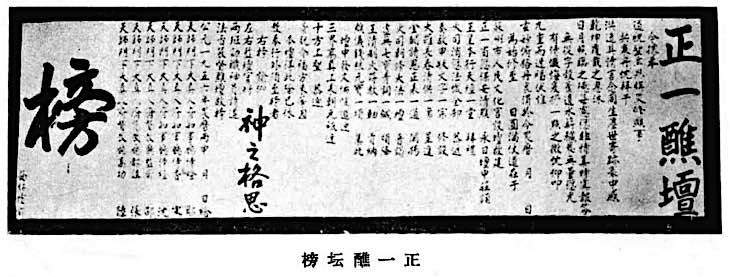

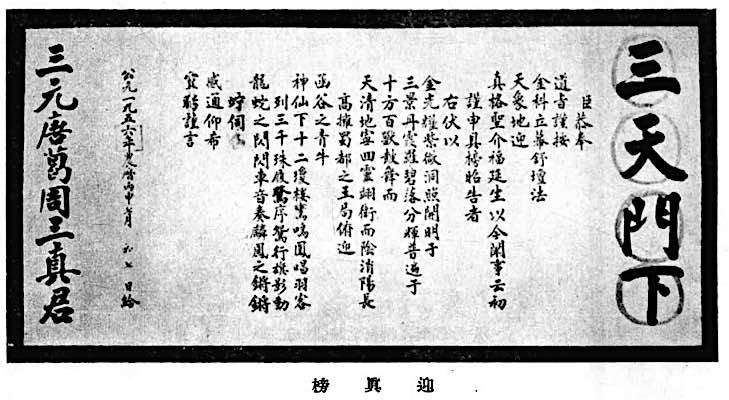

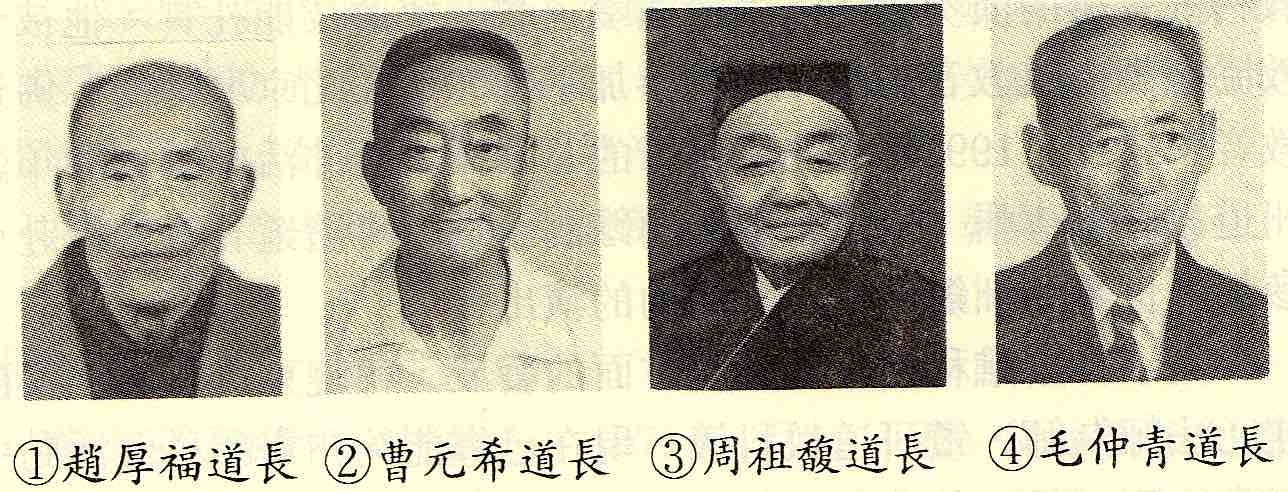

Placards proclaiming the Offering ritual.

Placards proclaiming the Offering ritual.

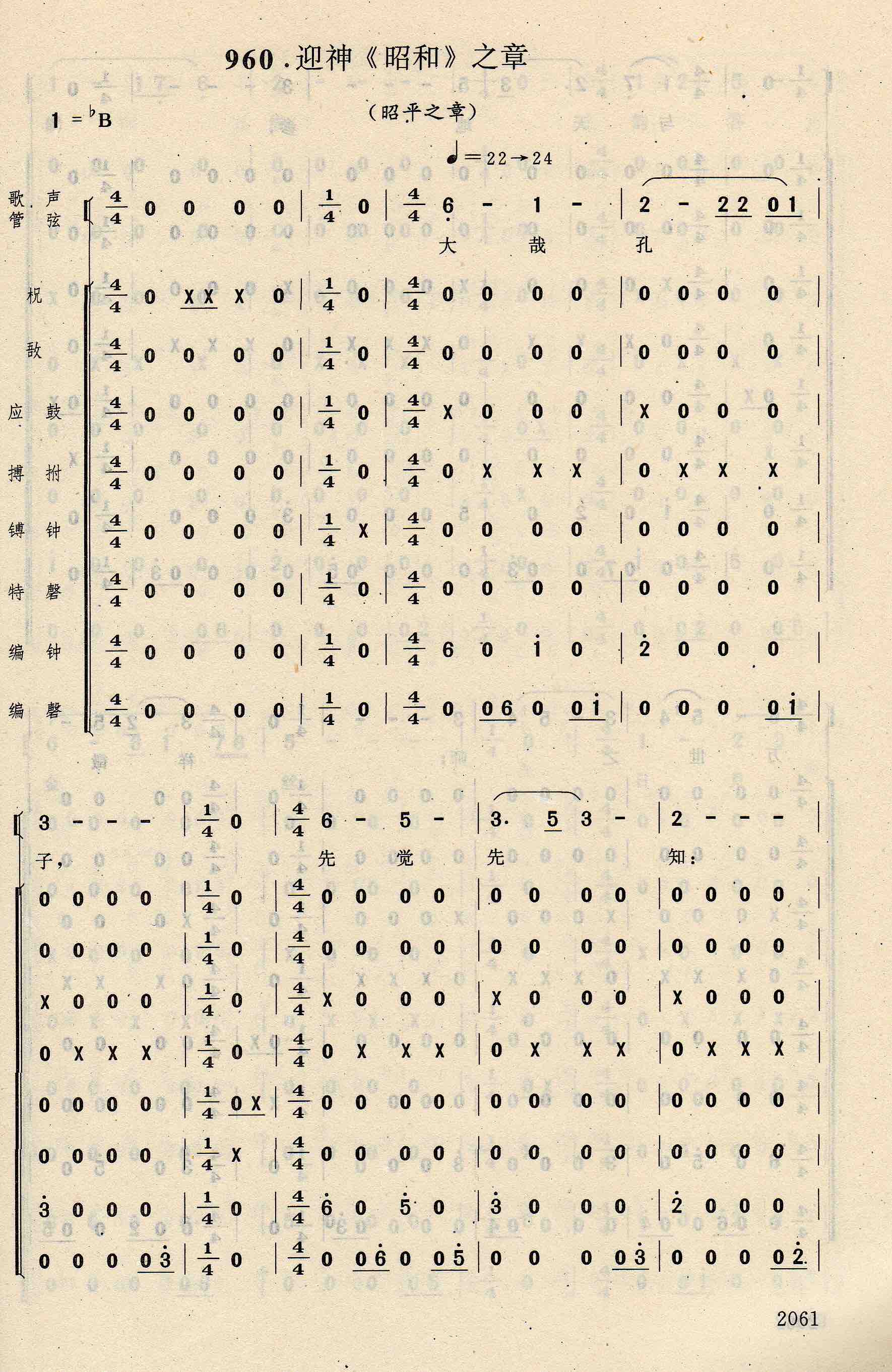

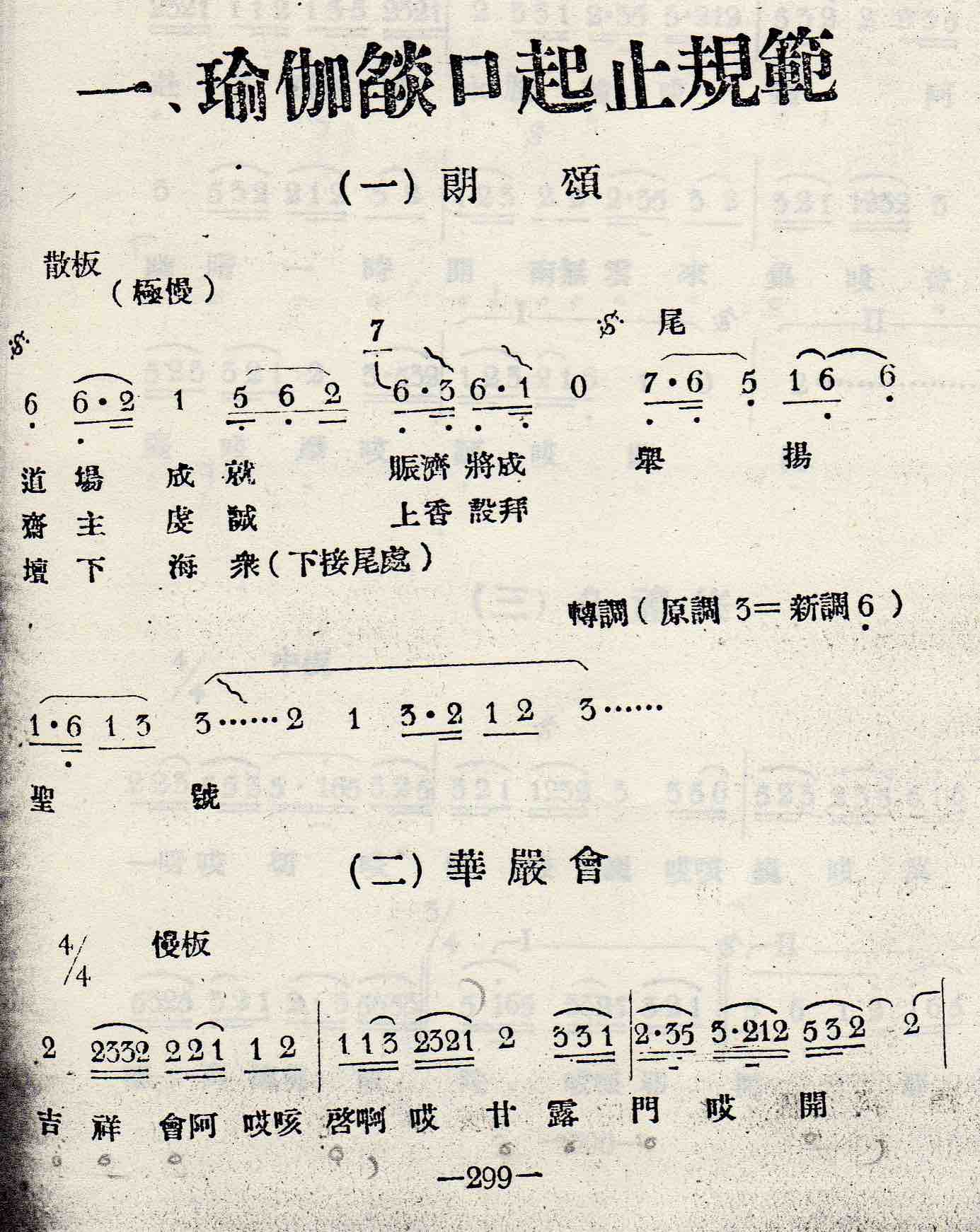

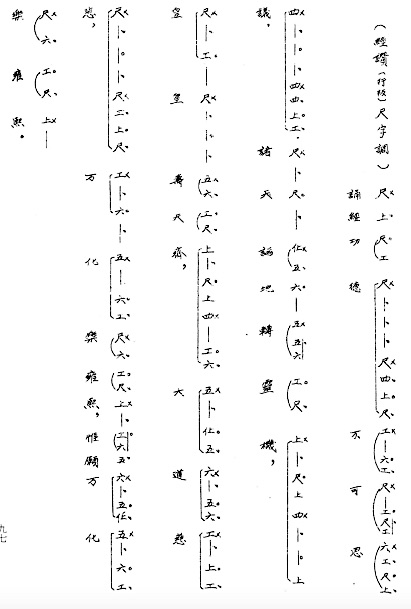

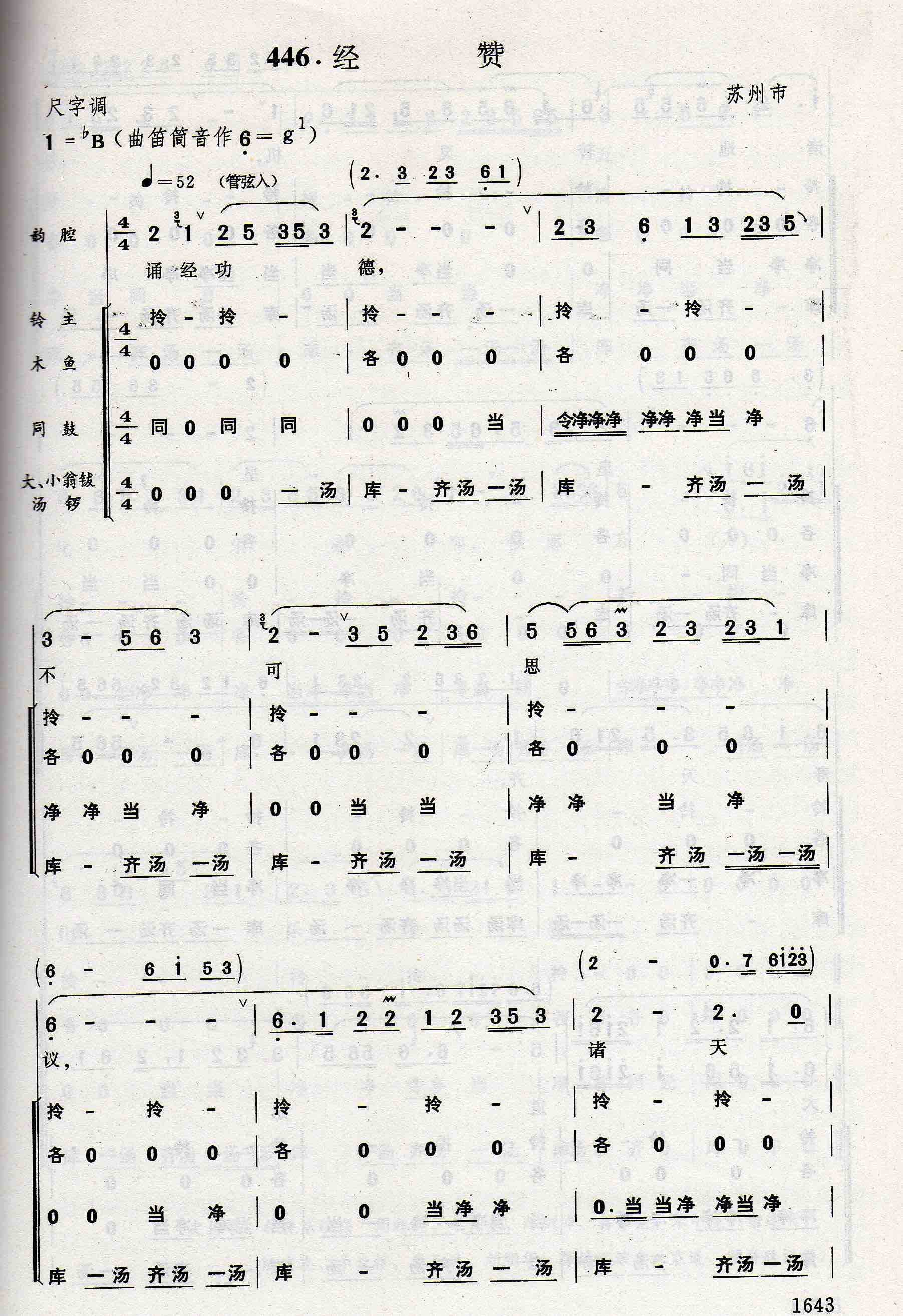

Opening of Songjing gongde, a widely used hymn in both temple and household Daoist groups.

Opening of Songjing gongde, a widely used hymn in both temple and household Daoist groups. Opening of Quanbiao ritual: instrumental Yifeng shu leading into Tianshi song hymn, whose text is the generational poem for the priestly lineage.

Opening of Quanbiao ritual: instrumental Yifeng shu leading into Tianshi song hymn, whose text is the generational poem for the priestly lineage. Opening of Songjing gongde hymn, transcribed by Anthology collectors from a 1990s’ rendition, also showing percussion accompaniment.

Opening of Songjing gongde hymn, transcribed by Anthology collectors from a 1990s’ rendition, also showing percussion accompaniment. Tianshi song hymn as transcribed by Anthology collectors.

Tianshi song hymn as transcribed by Anthology collectors.

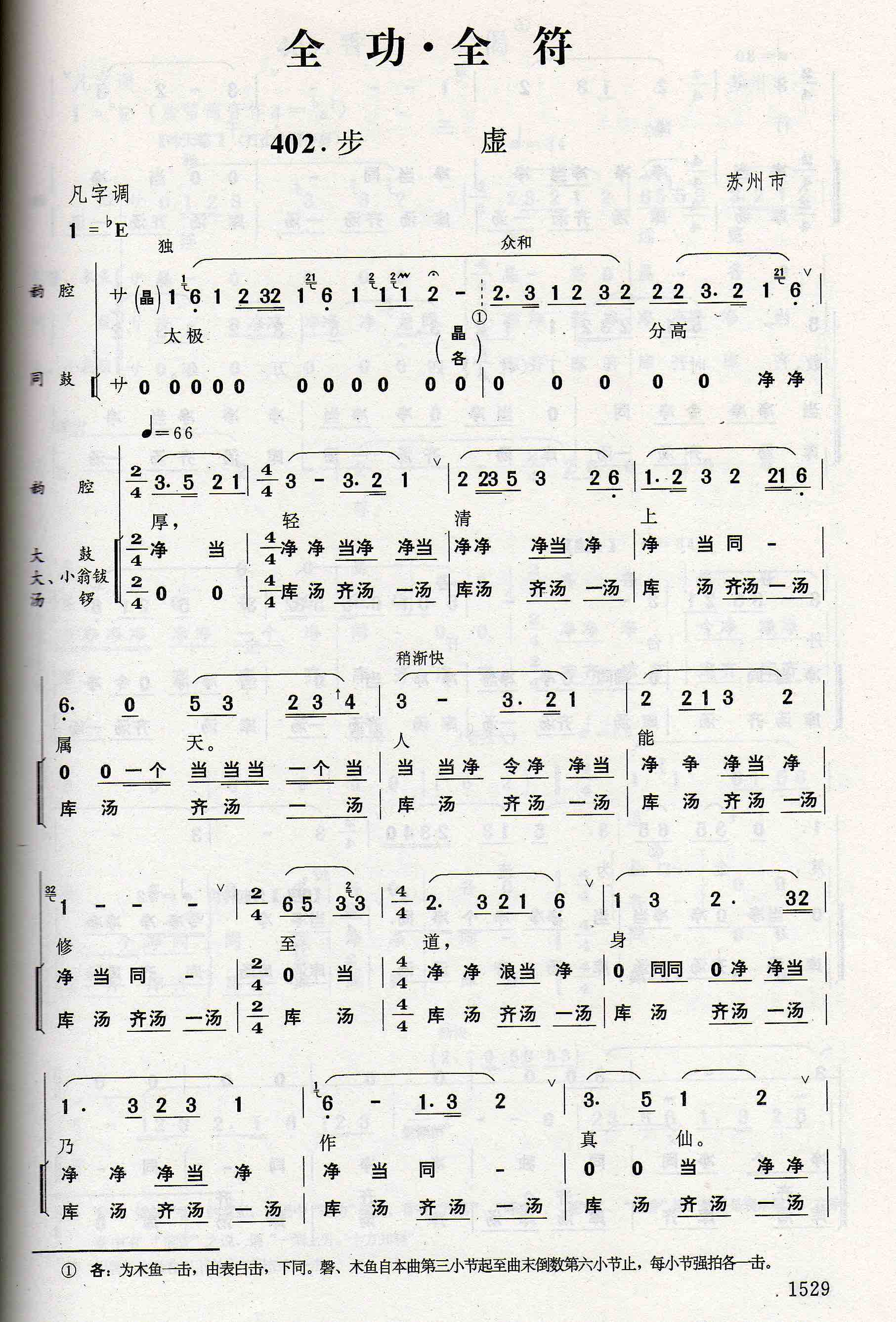

Opening of Taiji fen gaohou hymn as transcribed in the Anthology.

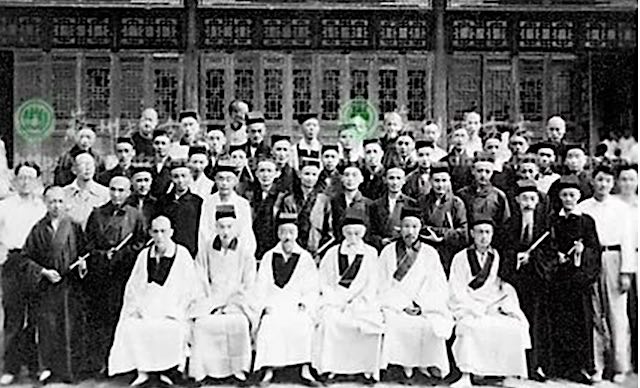

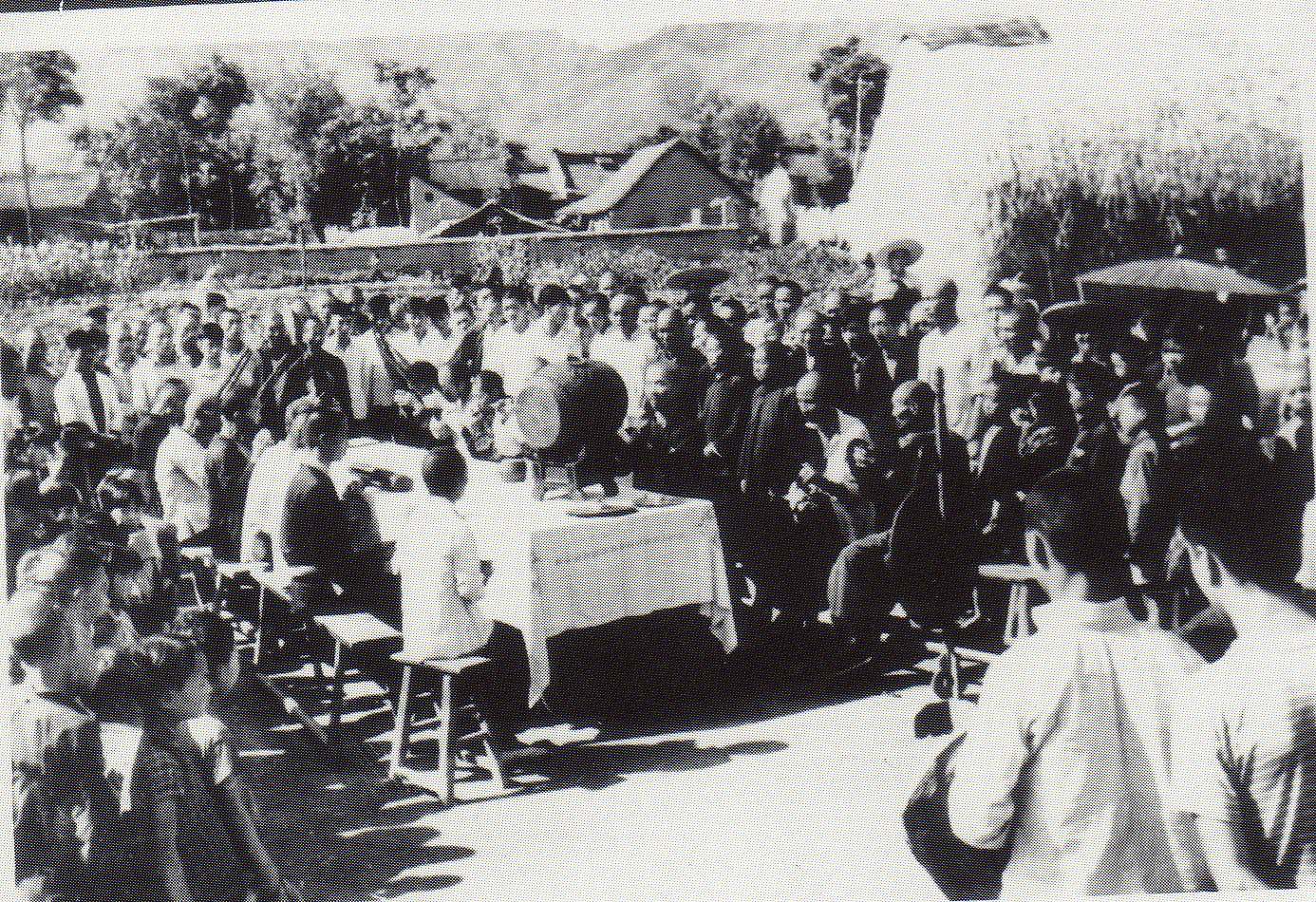

Opening of Taiji fen gaohou hymn as transcribed in the Anthology. The Wanhe tang:

The Wanhe tang:

Exiles in a “special settlement” in western Siberia, 1933.

Exiles in a “special settlement” in western Siberia, 1933. “Kulaks” exiled from the village of Udachne, Khryshyne (Ukraine), early 1930s.

“Kulaks” exiled from the village of Udachne, Khryshyne (Ukraine), early 1930s. Yevdokiia and Nikolai with their son Aleksei Golovin (1940s).

Yevdokiia and Nikolai with their son Aleksei Golovin (1940s).

Nikolai Kondratiev’s last letter to his daughter, 1938.

Nikolai Kondratiev’s last letter to his daughter, 1938. Elena Lebedeva with her granddaughters, Natalia (left) and Elena Konstantinova,

Elena Lebedeva with her granddaughters, Natalia (left) and Elena Konstantinova, Left: Zinaida Bushueva with her brothers, 1936.

Left: Zinaida Bushueva with her brothers, 1936.

The list of countries also evokes the Olympic medals table—with USA, China, and even the UK ranking high, pursued by France, Germany, Australia, Japan, and so on. Further down, Romania, Thailand, and Brazil put in plucky performances. I like some of the fortuitous juxtapositions that it produces daily (left).

The list of countries also evokes the Olympic medals table—with USA, China, and even the UK ranking high, pursued by France, Germany, Australia, Japan, and so on. Further down, Romania, Thailand, and Brazil put in plucky performances. I like some of the fortuitous juxtapositions that it produces daily (left).

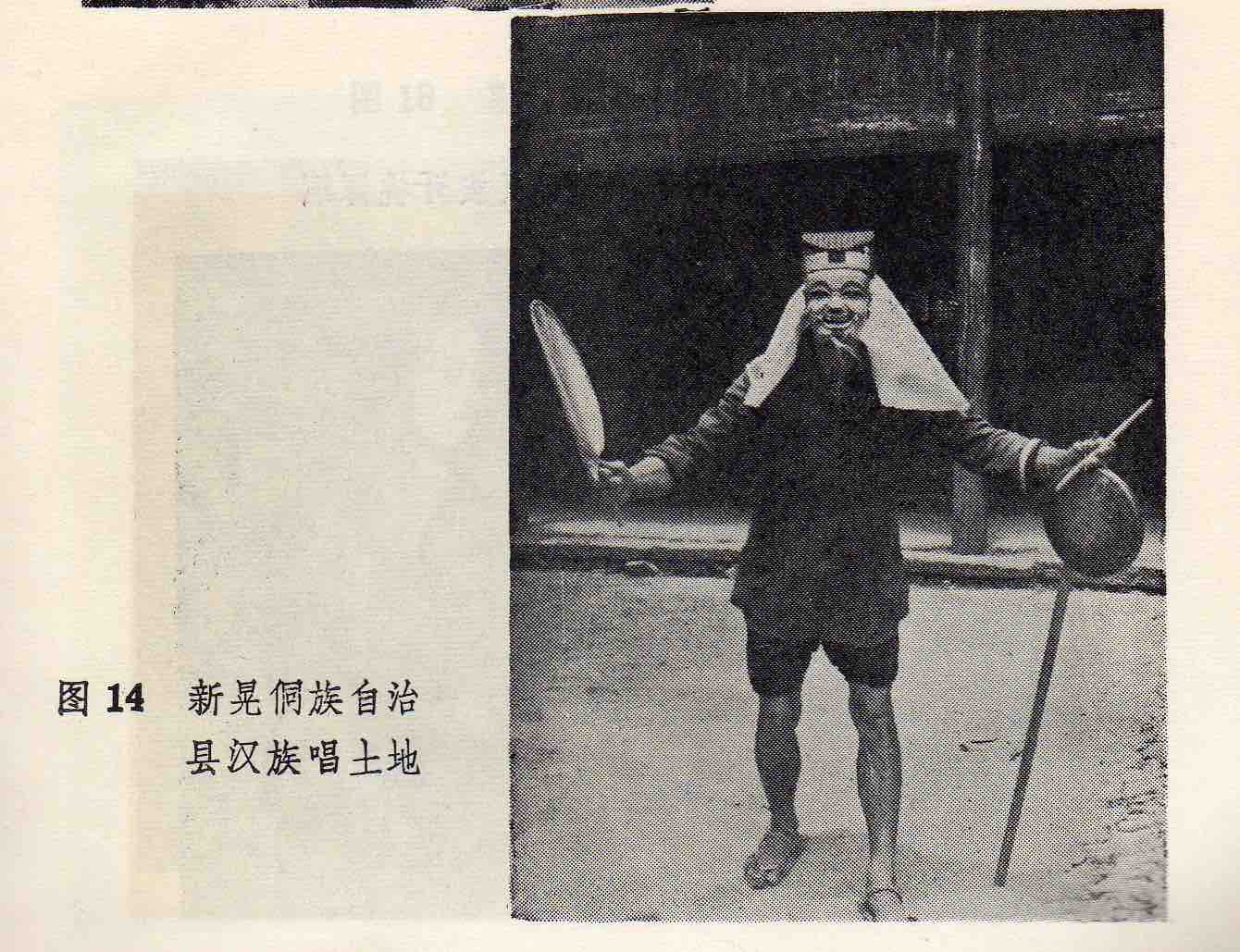

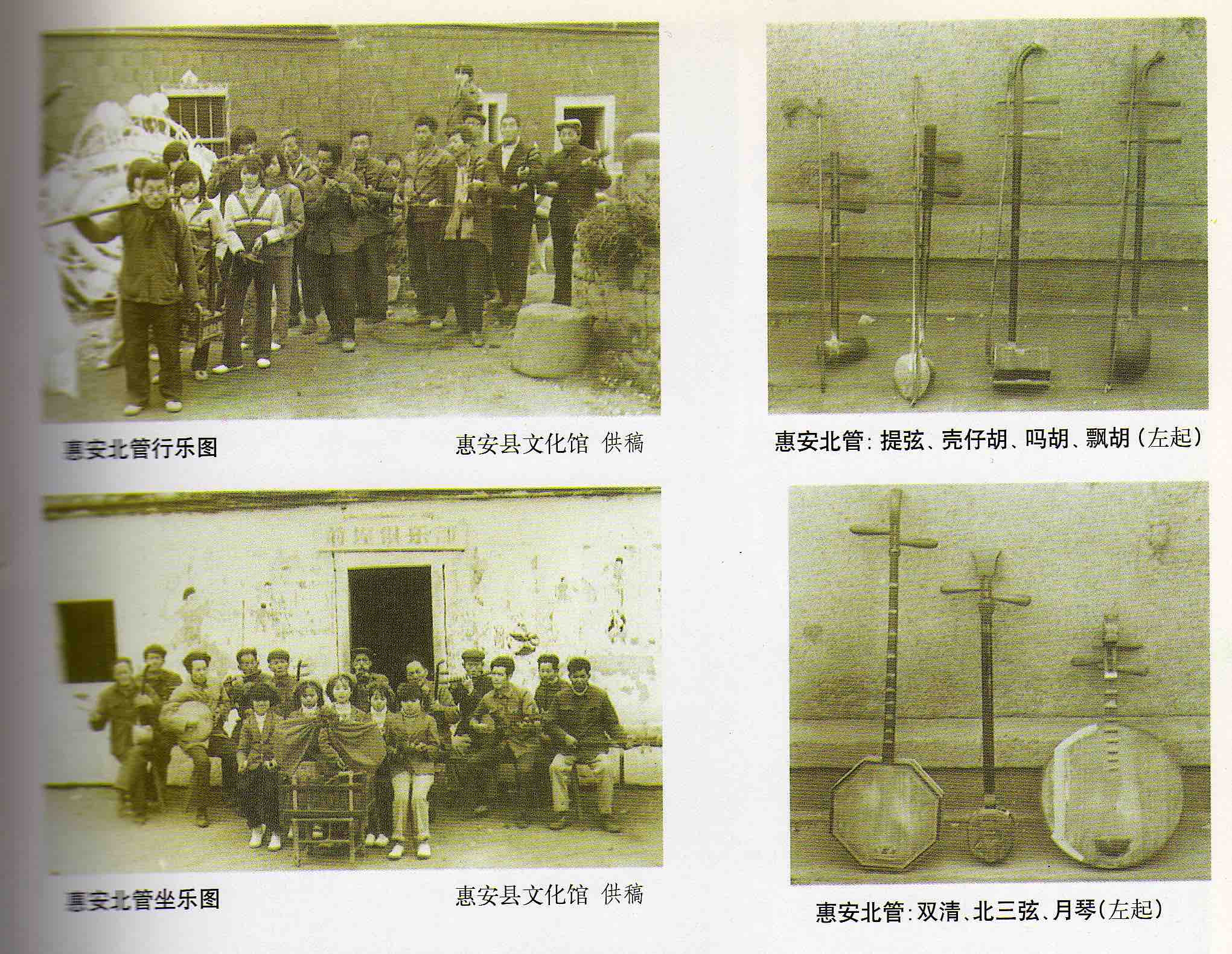

To accompany my new post outlining diverse performance genres of

To accompany my new post outlining diverse performance genres of

After

After