Towards a dynamic approach to material artefacts in diachronic social context

Further to my previous post giving background on material support for amateur ritual associations on the Hebei plain, I now focus on Gaoluo village, whose four ritual associations all preserve a wealth of ritual artefacts. Here our prolonged fieldwork allows us to “break through the 1949 barrier” by incorporating the easily-neglected Maoist era into the wider picture both before the Communist victory and since the 1980s’ liberalisations.

Again, please excuse the considerable duplication with many of my previous writings on Gaoluo—in particular my book Plucking the winds, and on this site, my pages on Ritual images: Gaoluo and the village’s three other ritual associations. [1]

To remind you, both South and North villages have their own ritual association, now commonly known as Music Association (yinyuehui, yinyue referring to the “classical” style of paraliturgical melodic instrumental ensemble); and both villages have their own Guanyin Hall Association (or Eastern Lantern Association, dongdenghui), now known as Southern Music Association (nanyuehui, having adopted the more popular style of “Southern music”). But whereas the misleading term “music association” has since become standard in the region, note that neither the 1930 nor the 1990 lists of South Gaoluo use the term: both texts (like their 1983 gongche score) refer to “Southern Lantern Association” (nandenghui), the 1990 list glossing it as “sacred society” (shenshe). So to stress yet again, this whole topic belongs firmly within the study of folk religion and society, far beyond “musicology”. Do watch my film on the 1995 New Year’s rituals in Gaoluo!

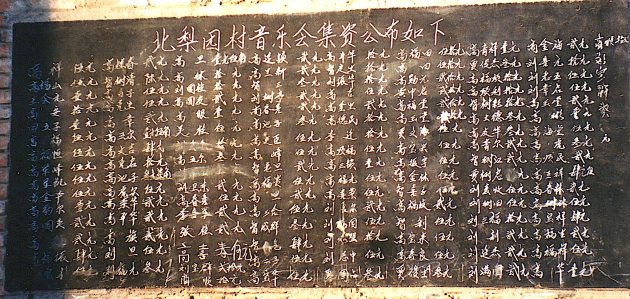

These two donors’ lists from 1930 and 1990 make striking exhibits, but the village’s other associations also suggest clues; having written about them separately, here I rework them into a diachronic account.

A common stimulus for creating new donors’ lists is the expenditure of replacing ritual artefacts (ritual manuals, god paintings, instruments, and so on); besides recording the contributions of named villagers, many lists provide detailed public accounts.

The 1930s

For our main ritual association in South village, one such list, which we saw adorning the lantern tent for the 1995 New Year’s rituals, was said to date from the late 19th century, but alas it was so faded as to be totally illegible. Instead, most handsome of the ritual artefacts on display was the 1930 donors’ list—apparently the only surviving list from before Liberation that we have found in the region:

Now if we saw this list on the wall of a museum, it would have limited potential. But since the tradition endures, not only can we witness rituals, hearing the wind and percussion music and vocal liturgy before the gods; but further, the descendants of the people featured in the list were able to provide considerable detail, putting the initiative in the context of the Republican era in the region. To summarise my discussion in Plucking the winds and in Ritual images: Gaoluo, during 1930 both associations in South village undertook a refurbishment of their ritual apparatus—apparently prompted both by the brief restoration of peace in the area after many years of fierce fighting between warlords, and by competition with the renewed energy of the village Catholics.

The 1930 list, entitled Wanshan tonggui (“The myriad charities return to the same source”), commemorates the commissioning of a major series of diaogua hangings from Painter Sun of Doujiazhuang village in Zhuozhou county just north. It records 92 heads of households, surely consisting of most of those then living in the southern half of South village which the association served, though some were doubtless too poverty-stricken to be able to afford even a minimal contribution. For all the beauty of the list, many (including all the womenfolk) were unable to read it.

The donations, ranging from 6 yuan to 5 jiao, totalled 109.83 yuan; the cloth cost 24 yuan, the paintings 61.5 yuan, and other expenses amounted to 33.83 yuan, leaving debts of 9.5 yuan. Five “managers” of the association are named at the head of the list: Cai Lin, Cai Ze, Shan Xue, Shan Chang, and Shan Futian (sketches in Plucking the winds, p.54). As their descendants recalled in the 1990s, all were prominent figures in the village, some of whom were also active as ritual performers.

Later in 1930, in preparation for the following New Year’s rituals, the South village Guanyin Hall Association also made a donors’ list for the commissioning of twelve new ritual paintings, listing four “managers”, two “organisers”, and three “incense heads”. The paintings were again made by Master Sun; the 1990s’ members also say he made new diaogua hangings for their association. In the years before the 1937 Japanese invasion, one Wang Laoguo from South Gaoluo painted more diaogua for them.

Further suggesting the ritual revival of the time, the early Dizang precious scroll of the Guanyin Hall Association in North Gaoluo contains a section recopied in 1932 (the precious scrolls are introduced here, and for Hebei, here and here).

Under Maoism

In the decades after the 1949 Communist revolution, many village ritual associations gradually became less active or ceased entirely. However, a close look belies the common notion that ritual life was in abeyance right until the 1980s’ reforms. For this crucial and ever more elusive period, material artefacts serve only as an adjunct to the memories of villagers.

With the new regime in its infancy, peace gave rise to hope for local communities long traumatised by warfare. Even as the collective system escalated, Gaoluo’s new village administration managed to embrace its traditional associations. The production teams used to give a little grain or other goods to support whichever association lay within their patch. The political climate didn’t dampen faith in village ritual associations: they continued to perform funerals and observe the New Year’s rituals in their respective lantern tents. Between 1950 and 1964 several groups of young men were recruited to learn both the vocal liturgy and the instrumental music; new gongche scores of the latter were compiled.

However, I doubt if the associations often dared hang out their ritual artefacts, and the atmosphere must have discouraged the making of donors’ lists. Our association didn’t make one between 1930 and 1990, but in 1952 the South village Guanyin Hall Association converted from their chaozi shawm-and-percussion music to the more popular style of “Southern music”. They invited the locally-renowned musician Hu Jinzhong from nearby West Yi’an village to teach them, giving him food and accommodation through the winter, but no fee, as ever. There was some official opposition to them learning the music, so the association sought no public donations; it still owned some land in the early 1950s, so it could buy instruments independently. Supporters merely “took care of a banquet” for the association, and no donors’ list was made.

The early 1960s

From 1961 to 1964, in the brief lull between the famine and the Four Cleanups campaign, ritual associations revived strongly throughout the Hebei plain, training youngsters in both the instrumental ensemble and the vocal liturgy. The latter tradition was in general decline on the plain, with the elders of the “civil altar” dying off. In Gaoluo, the vocal liturgy of South and North village Guanyin Hall Associations effectively came to an end with the deaths of Zhang Yi in 1950 and Shan Yongcun around 1956. Only our South village ritual association had a group of keen teenagers who came forward in 1961 to study the vocal liturgy with senior masters. But elsewhere the shengguan instrumental ensemble increasingly came to represent the scriptures before the gods.

One might imagine the early 1960s’ revival prompting our association to compile a new donors’ list, but perhaps the leaders were wary of creating such a public pronouncement. However, in 1962 the South village Guanyin Hall Association used its 1930 list to add a new list of donors.

And in 1964 the Gaoluo village opera troupe, not inhibited by the taint of “superstition”, commemorated its revival in a donors’ list (composed by Shan Fuyi), with the 280 donors representing the great majority of households in North and South villages at the time. The list records the donation of c450 yuan in total.

For both the ritual associations and the opera troupe, the early 1960s were a cultural heyday such as they had not been able to enjoy since the early 1950s, reflecting the social recuperation after the famine afforded by a central withdrawal from extreme leftist policies. Little did they know that political extremism was once again to disrupt their lives still more severely; the optimism of their declarations was soon to look naive and hollow.

Since the 1980s’ reforms

In the Hebei villages, as throughout the whole of China, the last two decades of the 20th century were particular in that their associations were reviving after at least fifteen years of stagnation—and even those that had been active until the eve of the Cultural Revolution had practised somewhat furtively. Thus they needed to replace a considerable amount of their ritual equipment.

In Gaoluo after the liberalisations following the collapse of the commune system in the late 1970s, the village “brigade” (dadui) gave 100 yuan a year to all the village’s main associations, which our South village ritual association spent on getting its sheng mouth-organs tuned. In the early 1980s they commissioned a new ritual pantheon of Dizang and the underworld, and compiled a new gongche score, but they didn’t yet create a new donors’ list.

However, the North village Guanyin Hall Association had a donors’ list made as early as 1981, to commemorate their own revival, written in elegant classical Chinese (text copied in Zhang, Yinyuehui, pp.128–9). This association had a reputation for observing the ritual proprieties, and preserved splendid “precious scrolls” from the 18th century, but their fine tradition of reciting them was going into decline even before Liberation. The first historical material on the list consists of four names (“transmitters of the ritual business”) from the 1920s. Unusually, having originally been a temple-based ritual association based on reciting the scriptures, they had diversified by adopting secular genres, acquiring opera in the 1930s, reformed pingju opera in 1951, “Southern music” in the 1960s (learned from their sister association in South village), and lion dancing in 1981.

The 1990s

As the economic liberalisations gathered pace and communal consciousness was attenuated, many village associations that had revived found it hard to maintain activity. In Gaoluo the 1990s were distinctive for the renewed energy provided by our fieldwork (Plucking the winds, pp.189–205).

After our first visit over the New Year’s rituals in 1989, our association now resolved to refurbish their “public building”, which they had reclaimed from the village brigade after the collapse of the commune system. This initiative was led by the then village chief Cai Ran, himself a keen member of the “civil altar”. After writing enterprisingly but unsuccessfully to the Music Research Institute in Beijing to request funding for the project, they managed to be self-sufficient in realising the project, with villagers donating money and labour.

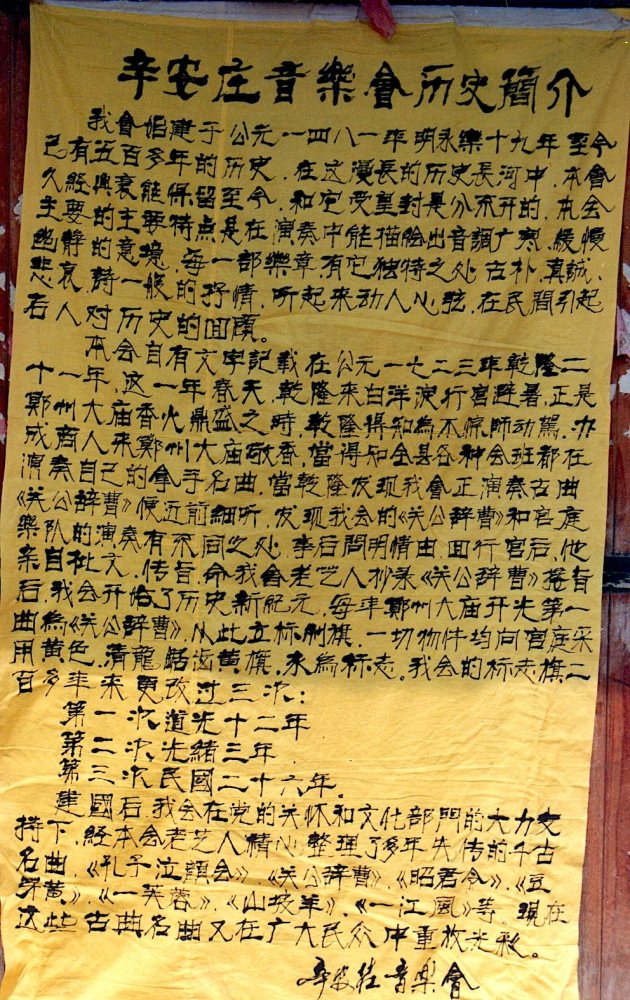

So in 1990 the leaders of our association invited Shan Fuyi to make a new donors’ list. His substantial text outlining the association’s history (see Ritual images: Gaoluo) makes clear that my visit was a stimulus for the project; still, it was written with no guarantee that outsiders would return.

The 1990 list names 270 heads of households. Still, villagers were becoming less conscientious about donating (see Women of Gaoluo, under “Rural sexism”).

From the 1930 and 1990 lists alone, we can hardly perceive change. The association still served the ritual needs of the villagers, and was still supported by most households in its catchment area. Without thick description from fieldwork and interviews, we might never know how ritual and social life were changing.

In the early 1990s there were several thefts of ritual artefacts in Gaoluo—but this served as a stimulus for the association to reclaim those that had been taken off by cultural authorities under Maoism.

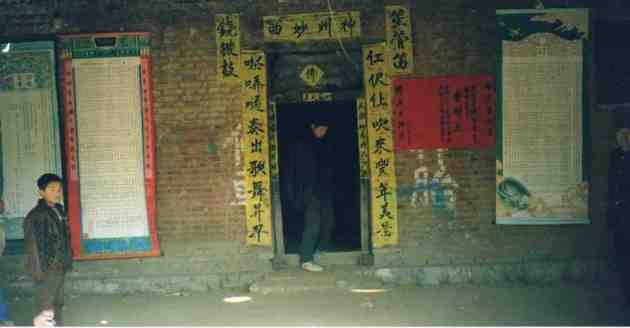

The lantern tent of the South village ritual association, 1998,

with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

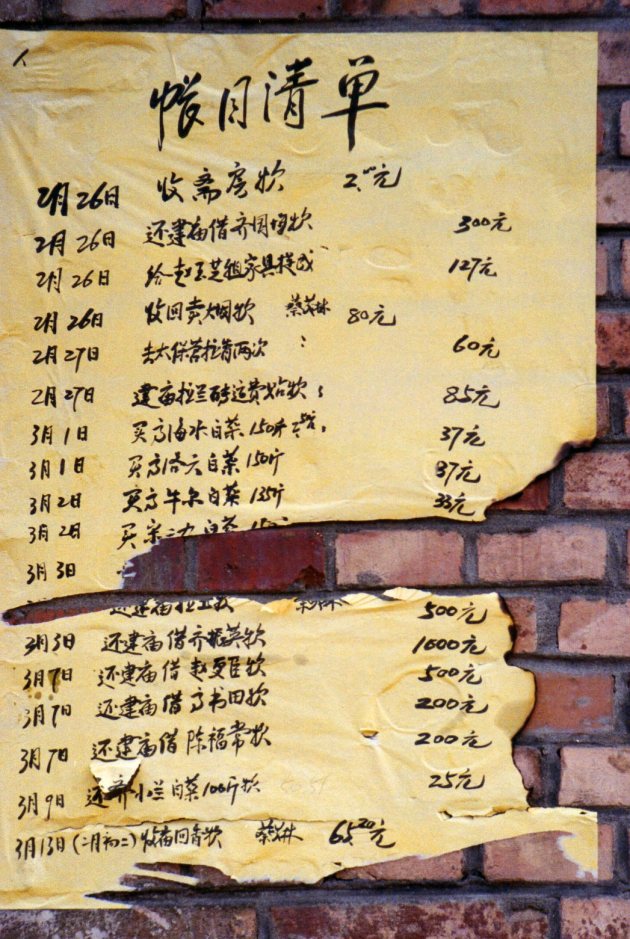

Our attention to the South village ritual association stimulated another competitive ritual flurry among the two villages’ other three ritual associations. For New Year 1990 the North village ritual association also had new ritual paintings made, of their own pantheon and the Ten Kings of the Underworld (for the donors’ list commemorating this initiative, see under Ritual images: Gaoluo). We also saw a more transient paper list of expenses from New Year 1992, pasted at the entrance to their ritual building, and already decrepit and hard to read by the following summer. They had received 690.47 yuan; they had incurred expenses such as buying coal, meat, vegetables, doufu, oil, salt, tea, firecrackers, tuning sheng, buying cloth bags for sheng, copying scores, and mounting ritual manuals and paintings—all conscientiously recorded. At New Year 1998 we saw their paper lists of income and expenses for the past year. Most of the association’s income had come from the hiring of crockery; donations had also been made when the association performed funerals (the rate being around 100 yuan). Some individuals had donated cash (one as much as 750 yuan), and the village committee had given 200 yuan. They had received 3,638.2 yuan (including 939.8 yuan brought forward from the previous year) and spent 2,992.2 yuan.

After the demise of the commune system, the South village Guanyin Hall must have revived along with the other associations by about 1980. Following our 1989 visit and the revamping of the ritual associations of North and South villages, they too had a surge of energy. For New Year 1992 they made a new donors’ list (image here) for the rebuilding of their humble ritual building, with this inscription:

The Eastern Lantern Association of South Gaoluo rebuilt its public building in 1992 AD under the People’s Republic of China, with the aid of the donors listed above. Total expenditure 2,984 yuan 4 jiao; 15 yuan surplus.

The list shows 215 household heads giving sums from 20 yuan to 2 yuan.

Conclusion

In all, community support for ritual life had not waned despite successive social upheavals. But new challenges were taking their toll: migration to the towns in search of work, state education, and popular media culture. Since my last visit in 2003, Gaoluo has continued to be transformed—notably by the arrival of the Intangible Cultural Heritage system, which I will address soon.

Static, silent material artefacts are most instructive when we can use them in conjunction with fieldwork and interview, helping us connect them to changing social life, filling in the gaps, learning more about practice and personalities over time. This is where the ethnographer has an advantage over the historian. I wish we had been able to find yet more detail—for instance on the 1950s: how funerals were changing, how calendrical rituals became less frequent, the decline of the vocal liturgy, and so on. We were lucky to be able to consult people who had taken part in the events commemorated in donors’ lists; but as time goes by, fewer villagers remain who can recall the early years of Maoism, let alone the “old society” before 1949.

[1] See the index of Plucking the winds, under “donations and donors’ lists”; Zhang Zhentao, Yinyuehui, pp.116–35, copies and discusses all the Gaoluo donors’ lists. On this site, note also the series of articles under the Gaoluo rubric of the main Menu.

The Li family Daoists perform the

The Li family Daoists perform the  Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

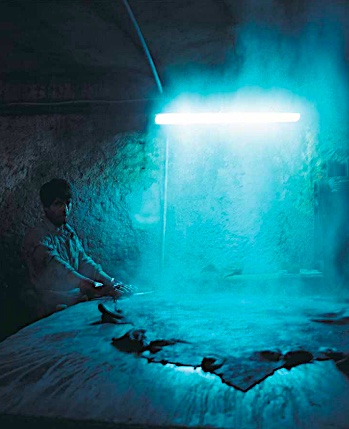

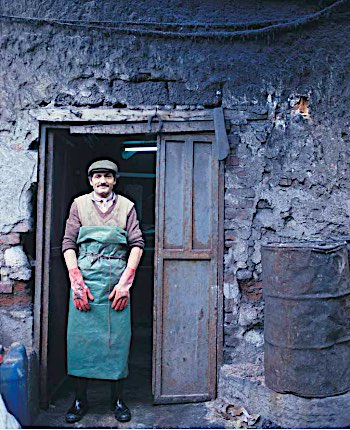

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

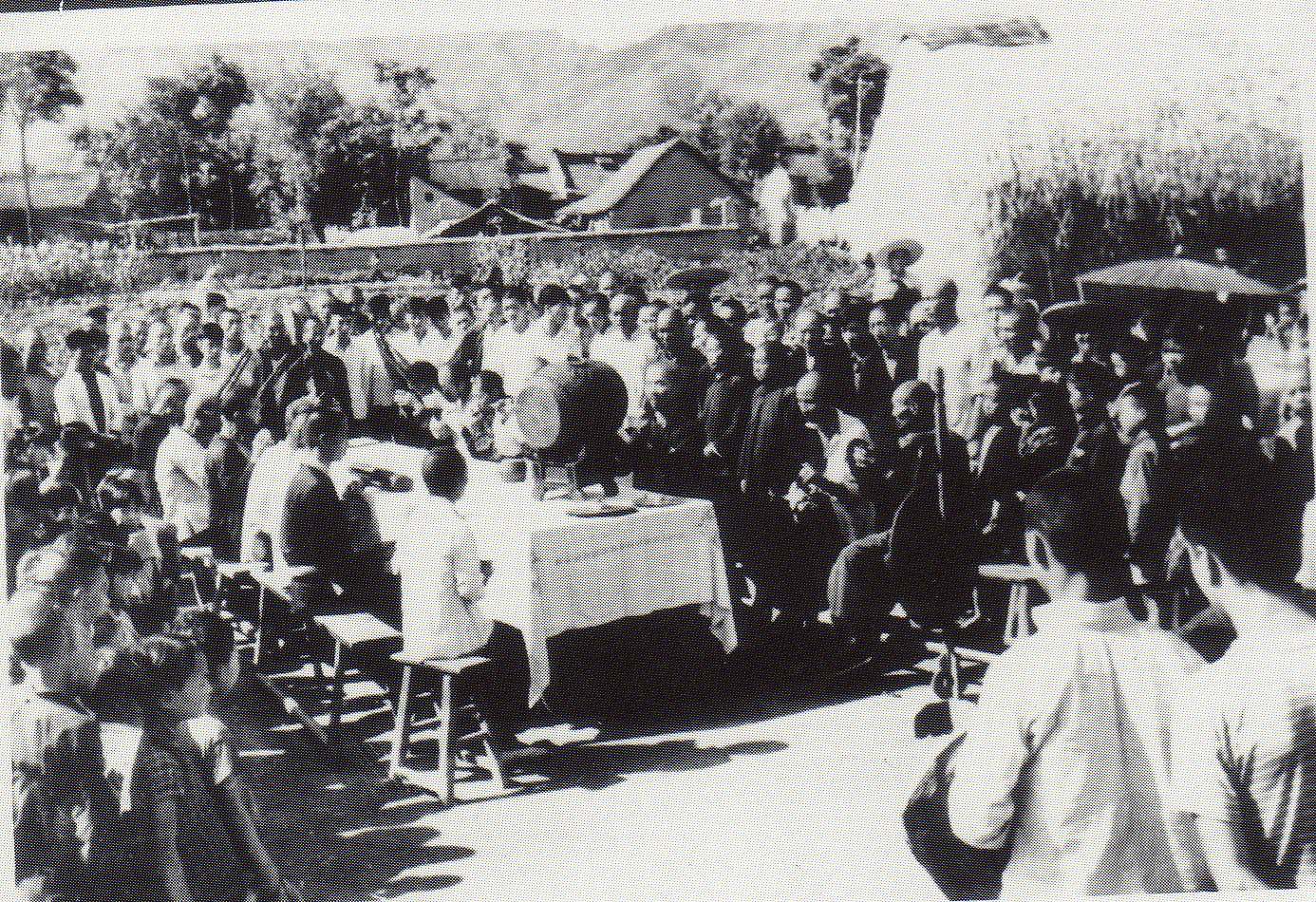

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

The Shanhua temple during the

The Shanhua temple during the

With Qiao Jianzhong (right) and Huang Xiangpeng, MRI 1989.

With Qiao Jianzhong (right) and Huang Xiangpeng, MRI 1989.

Qiao Jianzhong (left) and Lin Zhongshu (2nd left), 2013,

Qiao Jianzhong (left) and Lin Zhongshu (2nd left), 2013,

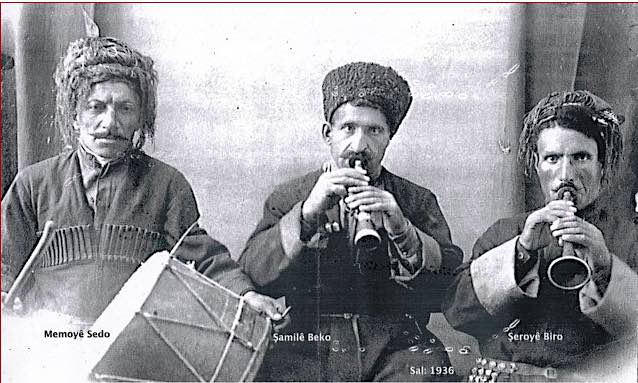

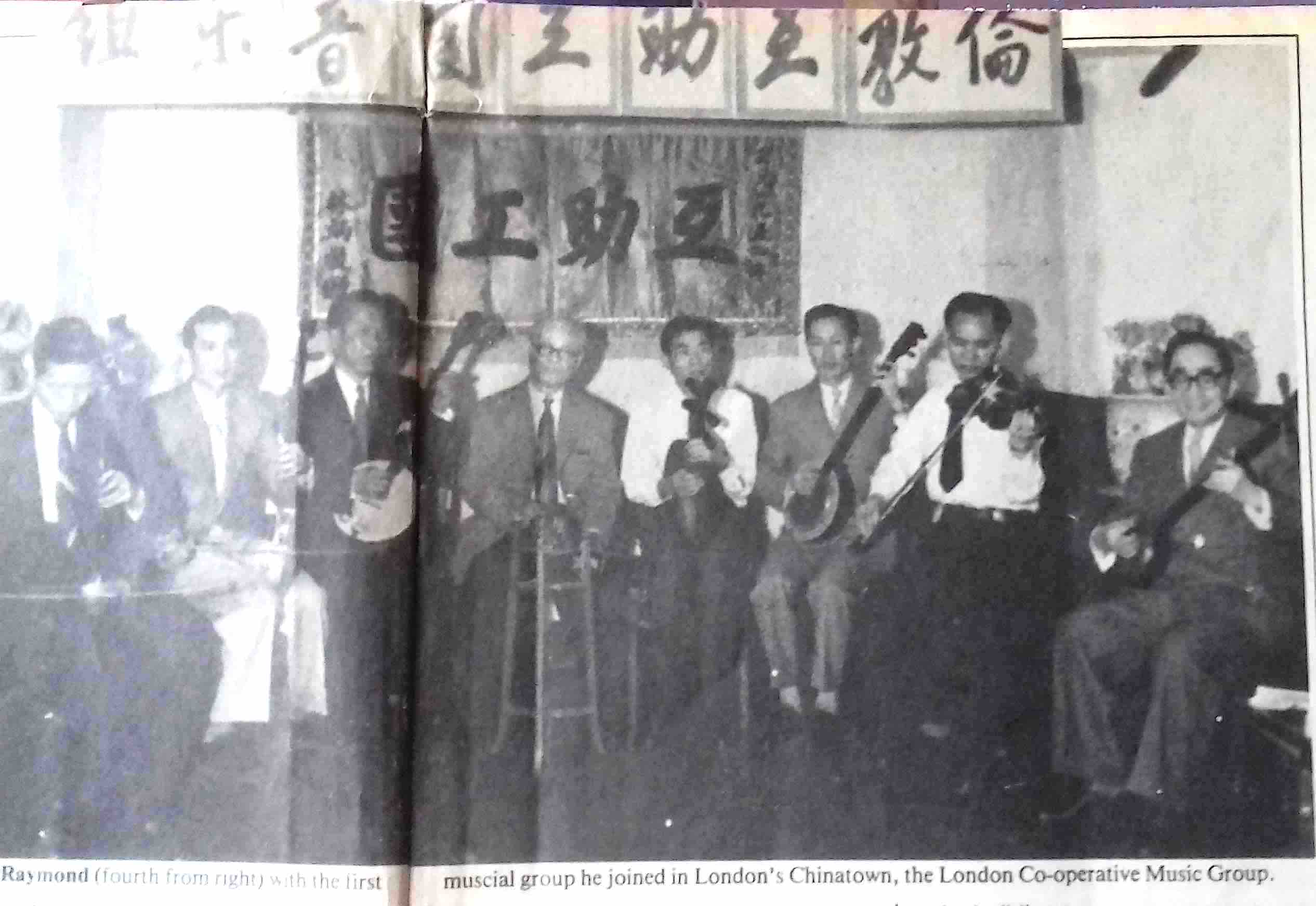

From The hundred thousand fools of God.

From The hundred thousand fools of God.

That musicologists were slow to appreciate all this reflects both ignorance and a prejudice against cultures seemingly lacking in notation or theory. Becker cites Hugo Zemp’s work on the panpipe ensembles of the ‘Are ‘Are in the Solomon Islands (preview

That musicologists were slow to appreciate all this reflects both ignorance and a prejudice against cultures seemingly lacking in notation or theory. Becker cites Hugo Zemp’s work on the panpipe ensembles of the ‘Are ‘Are in the Solomon Islands (preview

This way of thinking has also given rise to impressive ethnographies of Western Art Music by scholars such such as

This way of thinking has also given rise to impressive ethnographies of Western Art Music by scholars such such as

So I’m grateful to the exhibition for stimulating me to revisit some of my own material from the field. In this I’m always in awe of the incomparable erudition of

So I’m grateful to the exhibition for stimulating me to revisit some of my own material from the field. In this I’m always in awe of the incomparable erudition of

This reflects another common difficulty: we often seek to document history through major, exceptional events, whereas for peasants customary life is more routine. And apart from artefacts, much of the history of this (or any) period lies in oral tradition—which doesn’t lend itself so well to exhibitions.

This reflects another common difficulty: we often seek to document history through major, exceptional events, whereas for peasants customary life is more routine. And apart from artefacts, much of the history of this (or any) period lies in oral tradition—which doesn’t lend itself so well to exhibitions. From

From

From Qing-dynasty Tianjin Tianhou gong xinghui tu 天津天后宫行會圖.

From Qing-dynasty Tianjin Tianhou gong xinghui tu 天津天后宫行會圖.

Mural (detail),

Mural (detail),

Large queues formed for the National Gallery concerts.

Large queues formed for the National Gallery concerts.

Map, CIA 1992. Source:

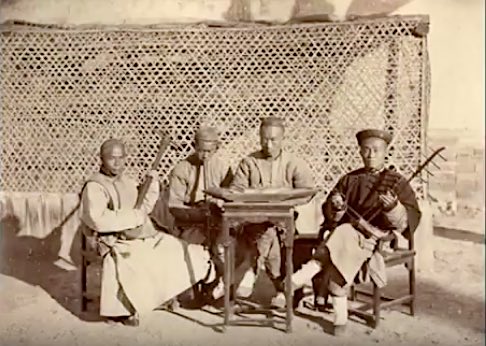

Map, CIA 1992. Source:  Musicians during the Festival of Folk Poets in Sivas, 1931.

Musicians during the Festival of Folk Poets in Sivas, 1931.

With the Mayor of Philadelphia.

With the Mayor of Philadelphia. Mother Divine signs her book for Li Shiyu.

Mother Divine signs her book for Li Shiyu.

Later we went into partnership with Hasan Yelmen and worked together for thirty years as Nurettin Keskiniz & Hasan Yelmen Co. When Hasan Yelmen stepped in, Panayot Sani, who had been making patent leather, moved back to his place. In those days, we could do chromium baking with the double-bath technique. But Hasan Yelmen managed to obtain better results by applying single-bath chromium baking. After he stepped in, we began to process chromium leather from sheep, designed for jackets. Thus it was we who first launched in Turkey the production of leather for jackets, which is in great demand today and which brings two hundred million USD of foreign earnings to Turkey. This is an important historical account. A Belarusian master tailor named Timochenko began to collect chromium sheepskin from us and sew leather jackets. When making chromium Moroccan leather for the railways, we had been highly skilled in the application of cellulose dye. The jacket material kept people warm, so it was in demand in the winter. Also, thanks to its cellulose finishing, it was water- and rain-proof. After learning how to sew leather jackets while working for Timochenko, Sabri Aykaç and Selahattin Tuncer left the Belarusian tailor. We supported them by providing them with jacket material on credit. Afterwards, Dona da Leon also began to sew leather jackets.

Later we went into partnership with Hasan Yelmen and worked together for thirty years as Nurettin Keskiniz & Hasan Yelmen Co. When Hasan Yelmen stepped in, Panayot Sani, who had been making patent leather, moved back to his place. In those days, we could do chromium baking with the double-bath technique. But Hasan Yelmen managed to obtain better results by applying single-bath chromium baking. After he stepped in, we began to process chromium leather from sheep, designed for jackets. Thus it was we who first launched in Turkey the production of leather for jackets, which is in great demand today and which brings two hundred million USD of foreign earnings to Turkey. This is an important historical account. A Belarusian master tailor named Timochenko began to collect chromium sheepskin from us and sew leather jackets. When making chromium Moroccan leather for the railways, we had been highly skilled in the application of cellulose dye. The jacket material kept people warm, so it was in demand in the winter. Also, thanks to its cellulose finishing, it was water- and rain-proof. After learning how to sew leather jackets while working for Timochenko, Sabri Aykaç and Selahattin Tuncer left the Belarusian tailor. We supported them by providing them with jacket material on credit. Afterwards, Dona da Leon also began to sew leather jackets.

Original caption (

Original caption (

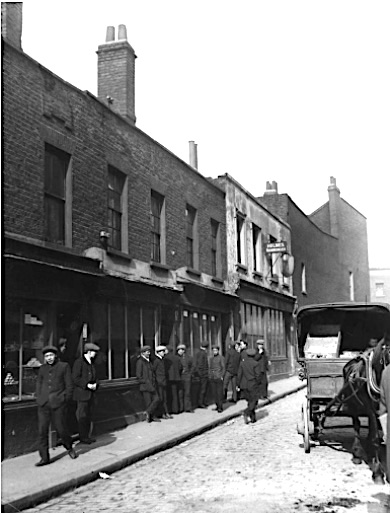

The shop in Chalk Farm.

The shop in Chalk Farm.

In the afternoon, first they performed at the entrance to the shops lining the street. As locals and visitors threw lira notes at the twirling feet of the two dancers, they gyrated gracefully down to pluck them up in their mouths. The group then made a base at the entrance of a side-street, performing a lengthier sequence beneath a large banner depicting Atatürk

In the afternoon, first they performed at the entrance to the shops lining the street. As locals and visitors threw lira notes at the twirling feet of the two dancers, they gyrated gracefully down to pluck them up in their mouths. The group then made a base at the entrance of a side-street, performing a lengthier sequence beneath a large banner depicting Atatürk

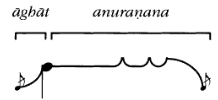

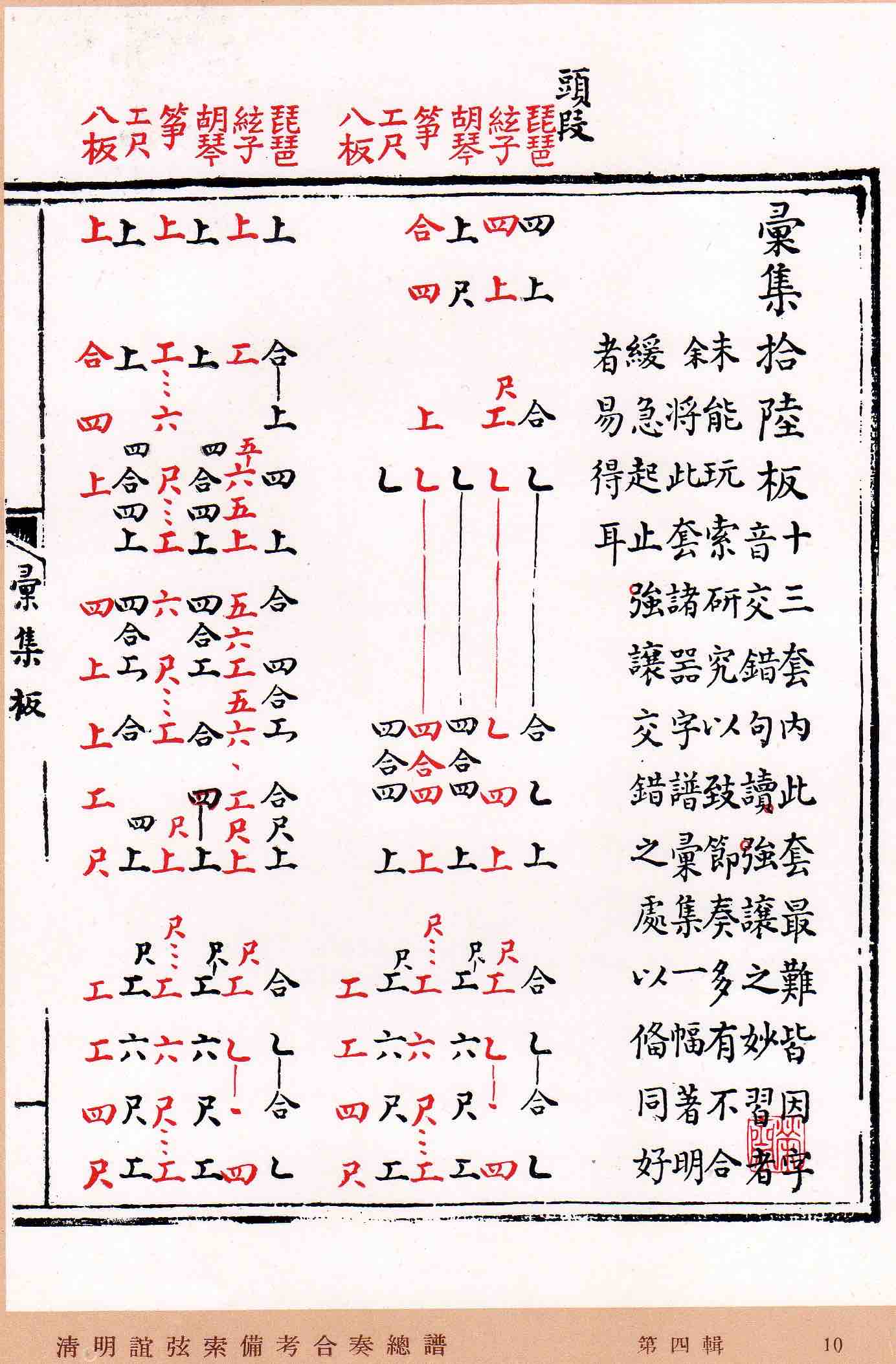

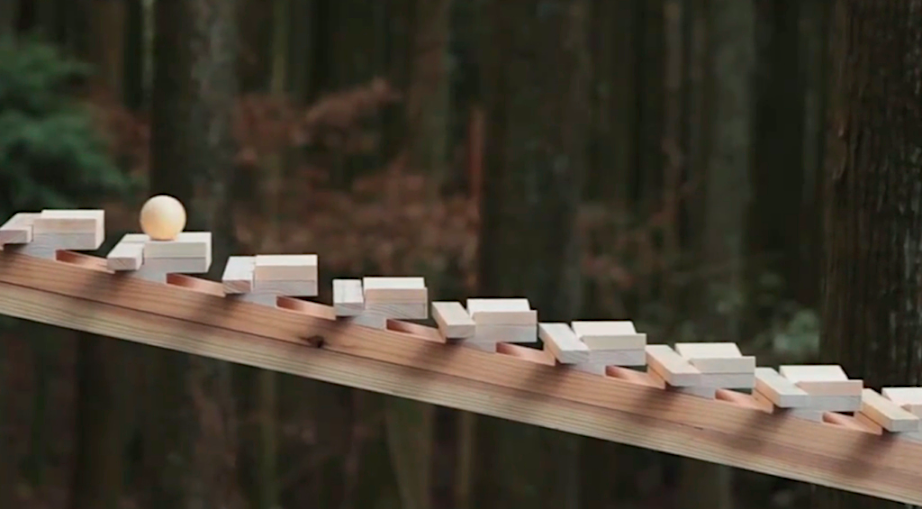

Opening of Guangling san:

Opening of Guangling san: