A fine new addition to the ethnography of Western Art Music * is

The title alludes to Sir Claus Moser’s diplomatic backstage words to an ageing diva. Both wise and delightful, the book is generously laced with deviant orchestral stories, but it’s much more than that. The blurb hardly does justice to the serious wider issues that Felix covers:

Orchestral life in Britain is thriving and anarchic, in turns chaotic, hilarious, and brutal. ** Perfection Is NOT the word for it is a personal, and mostly affectionate, account of life amongst the extraordinary characters who lead their over-stressed lives in this unusual world, surrounded by music but driven by everyday anxieties, and always defying the best efforts of administrators, bureaucrats, and conductors to tame the unruly beast which is a professional orchestra.

Felix makes a most sympathetic narrator. An orchestral and chamber bassoonist of note (possibly top C, as in The Rite of Spring), he has the rare distinction of having graduated to the role of managing some of the leading early music bands that have shaken up the scene since the 1970s. So while orchestral musos tend to take a dim view of administrators, Felix has the advantage, or misfortune, to have straddled both sides of the fence; he adopts the “poacher turned gamekeeper” metaphor, and one thinks of the common transition from football player to manager.

Chapter 1 opens with a priceless, if harrowing, blow-by-blow account of his first encounter with Pierre Boulez in 1972 upon being summoned at short notice to dep for a rehearsal with the BBC Symphony Orchestra (his very first professional gig, to boot)—an ordeal which becomes ineluctably more excruciating. After this it may be hard to hear the divine slow movement of the Brahms 1st piano concerto with the same ears. Unlike the viola player singled out during a Mendelssohn rehearsal, Felix didn’t even manage a pithy riposte.

Although his ordeal at the hands of Boulez was exceptional, musicians are keen to get revenge on their overlords by maestro-baiting, of which we are treated to several examples. He also has some good instances of corpsing.

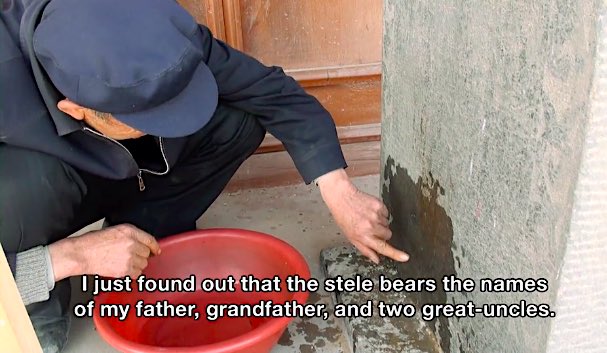

There are cameos from the renowned clarinettist Jack Brymer (an incident that precisely parallels one about the conductor Eric Leinsdorf) and the then rather less renowned Tony Pay (cf. this story). As on tour, and with my fieldwork in China (e.g. here), Felix delights in chains of stories. Alcohol, soon to be a pervasive theme of the book, enters the fray with the BBC’s principal horn Alan Civil—and one might add the wealth of stories about trumpeter John Wilbraham.

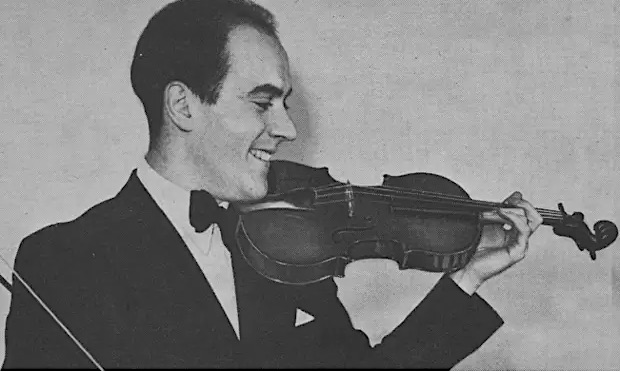

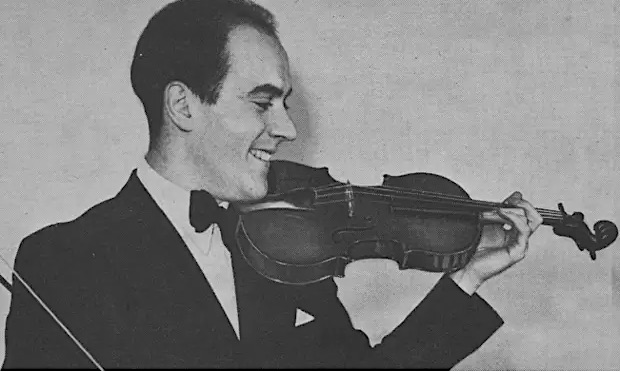

The pressures of touring were alleviated by excessive drinking. Felix pays tribute to the “sublimely gifted” violinist Alan Loveday, stories about whose travails with alcohol became legendary. On tour with the Academy of St Martin-in-the Fields (in which Felix played for fifteen years), conductor Neville Marriner had to lock Alan into his hotel room every evening—ensuring that he never once made it onto the concert platform, thus achieving “a feat that many musicians would think ideal, a tour without concerts”.

Alan was a talented bridge player, a taste that Felix shared. ••• He eventually took the road to recovery. He was keen to take up period-instrument performance, but never got round to it—as Felix observes, “if sober, he could have brought great critical credibility to this new world”. Felix’s tribute to Alan’s eccentricity and deep love of music leads him to stories about the iconic Francis Baines.

After this heady introduction to the orchestral world, Chapter 2 “An Oxford overture” returns to Felix’s upbringing with a perceptive account of the “tremendous intellectual intensity” of the post-war years there. Second of five children, he was deeply grateful for his education at the Dragon School (“a culture of kindness, politeness, and humanity”, enriched by its bizarre collection of characters on the teaching staff). Less happy at Winchester, he managed to leave school at 16, with the support of his wise mother. In the holidays he attended National Youth Orchestra courses.

Reading between the lines, it must have been through the rational enquiry of his distinguished philosopher parents that he acquired a seriousness and vision that his initial career as bassoon player was unlikely to satisfy. Sitting in on their dinner parties, he also inherited their taste for wordplay.

In Chapter 3, suitably titled “Five in a bar” (which is quite drôle enough without venturing to Tchaikovsky, Brubeck, and Balkan folk music), Felix recalls his happy, if blurred, days in the Albion Ensemble, a wind quintet seemingly modelled on the Famous Five—making a welcome occasional relief from the fraught struggles of the orchestral world. Felix opens the chapter with the convoluted story of a live broadcast for US TV.

It was soon after this lamentable episode (perhaps even because of it) that the Albion Ensemble’s capacity for resilience and self-preservation came to the attention of the British Council.

The quintet was now despatched to “countries in which self-reliance and an ability to deal with the unexpected would be at least as important as giving concerts”. Their adventures began with a five-week tour of the Far East. In China they learn the perils of official banquets (inexplicably, the quintet’s minders didn’t think to introduce them to their counterparts among household Daoists in the north Chinese countryside). In South Korea their provincial travels are given an extra edge by having very little idea of where they were supposed to be when, or how to get there. The quest for alcohol becomes ever more compelling. In the Philippines they succumb in turn to a gory bout of food poisoning, as they pass a hospital bearing the name of “The Antenatal clinic of the Immaculate Conception”.

Chapter 4, “Trials and errors”, takes us to the early music movement (note the work of Richard Taruskin and John Butt), in which Felix played a major role both as player and manager. The 1980s were a golden age for London’s freelancers, stimulated by the new CD format, film sessions, and touring; still, Felix was feeling the fragility of freelancing, “a house of cards which could collapse at the slightest unfavourable gust”.

Inspired by the innovations of Harnoncourt, Leonhardt, and Brüggen, he now expanded into “period instrument” performance. We find erudite notes on reviving the French bassoon that had lost out to its German counterpart; and on pitch standards adopted by the movement (a=415 being a fair compromise for the wide range used in baroque times, whereas a=430 for the classical era was a concoction imposed by Decca at an Academy of Ancient Music meeting).

Felix spent a period on the Music Advisory Panel of the Arts Council, entrusted with the task of finding a niche for WAM in a diverse market, which gave him serious reservations about box-ticking PC and committees’ fear of elitism. I’m sure he could offer a detailed critique of my own argument in What is serious music?!; indeed, my global view is All Very Well, but promoters inevitably find themselves having to fight for their particular corner of the bazaar.

Meanwhile he took a correspondence law course. Felix and his wife Julie eventually mastered the invidious competition for adoption, learning to guess the expected answers to rigorous questionnaires.

In Chapter 5 Felix recounts the invention of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment from 1985 (I was glad to learn that it was Chris Hogwood who coined its alternative name Age of Embezzlement). As Felix reflected,

London’s freelance musicians had achieved a remarkably dominant international position in period instrument performance but were now in danger of becoming stuck at their current level of (relative) mediocrity.

The various orchestras were closely identified with their founders (Hogwood, Pinnock, Gardiner, Norrington, and so on), but the pool of performers overlapped. “Our owners/proprietors were building international reputations based on the numerous recordings which we, the humble workers, had been making for them”. Meanwhile there was no platform in London for the great continental directors like Harnoncourt, Leonhardt, Brüggen, and Kujken; moreover, the scene, dominated by “semi-conductors” (in Norman Lebrecht’s fine term), was closed to “real” maestros from the modern symphonic world who might offer new insights into the repertoire, like Charles Mackerras (for whose splendid anagram, click here), S-Simon Rattle, and Mark Elder.

This led to the forming of a new orchestra that would engage its conductors, not the other way around. The financial challenge was daunting. But the success of Rattle’s concert performance of Idomeneo in 1987 led to an annual summer residency at Glyndebourne, and record contracts were soon secured. By 1988 Felix found himself managing the orchestra, negotiating projects with institutions like the South Bank Centre and the Proms while attempting to entice the busy continental maestros who had originally inspired him.

Left, Frans Brüggen; right, Trevor Pinnock.

By 1993, amidst difficult decisions over the orchestra’s personnel, Felix had to resign. From 1995 he managed the English Concert, which he found himself having to re-invent, as described in Chapter 6. Under the benevolent Trevor Pinnock the orchestra had thrived, but their recording contract was soon to expire, and another identity crisis loomed. Whereas Felix’s challenge at the OAE had been to create a clear and sustainable identity after a frenetic set-up, here the issue was the mirror image: “how to create a new and exciting identity for an already-successful organisation in danger of being overtaken by younger competitors”. But, as he reflects, the two orchestras did have one thing in common: neither had any money.

The English Concert had a remarkable success in staging Haydn’s puppet opera Philemon und Baucis. Here Felix gives another nice aside on the history of marionette theatre in England and on the continent; and he notes the relatively recent tradition of orchestral string sections using the same bowings.

Felix wrestles with fiendish logistics for the US tour of the Brandenburg concertos. At post-concert receptions he finds himself in the role of grown-up, nervously observing the players’ antics, with which he is all too familiar. Organising a Matthew Passion tour around concerts in Spain presents further scheduling challenges. Much as we love the bars there (and I, at least, love the flamenco), travelling around is indeed gruelling, as a later “tour from hell” confirmed (for the steady erosion of touring, see note here).

With Trevor Pinnock retiring, and the inspired leader Rachel Podger also leaving, Felix was delighted to find the equally prodigious Andrew Manze to direct the band from the violin. Rachel and Andrew’s Bach double at the Proms is one of my most treasured moments; and on tour, apart from his inspired playing, while we were waiting at Chicago airport Andrew told me one of my very favourite stories, which you can find here.

But while Felix envisaged a return to baroque music, in which the English Concert had made its mark, Andrew was now keen to pursue the fashion for a later repertoire, as he began to set his sights on conducting. With the 2008 recession causing further problems for festivals and promoters, Felix moved on again. Meanwhile his swansong on the bassoon came when he too achieved the ideal of appearing in an orchestra without having to play in it, miming in costume for a TV re-enactment of Handel’s Water music in a barge on the Thames. ****

Chapter 7, “Double bar: when the music stops”. After leaving the English Concert, Felix worked to find funding for some other projects—including an unfulfilled plan to restore the Notting Hill Coronet cinema to its original function as a music theatre. The building turned out to be owned by the Elim Church, whose largest congregation was at the Kensington Temple nearby—prompting another fine graffiti story. But by this time Felix was seeking a path away from the world of music. Having long served on the Music Advisory Panel of the Radcliffe Trust, he now joined the board of trustees, soon becoming chairman, still devising new projects. Again he offers thoughts on the bureaucratic dangers of the “Age of Regulation”. *****

It’s such a pleasure to read Felix’s memoir, by turns revealing, wise, and hilarious—sometimes all at once. Rush out and buy this book!

* Note e.g. Christopher Small’s Musicking, and Bruno Nettl’s Heartland excursions; see also Professional music-making in London (Stephen Cottrell); and for New York, Mozart in the jungle (Blair Tindall). Cf. Deviating from behavioural norms (links there including the kangaroo and sardine stories; more in the WAM category under “early music” and “humour”), and Alternative Bach.

** For punctuation nerds: as is my editorial wont, I supply the Oxford comma in such lists—all the more suitable given Felix’s background (albeit depriving us of the pleasures of formulations like “I would like to thank my parents, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Madonna”).

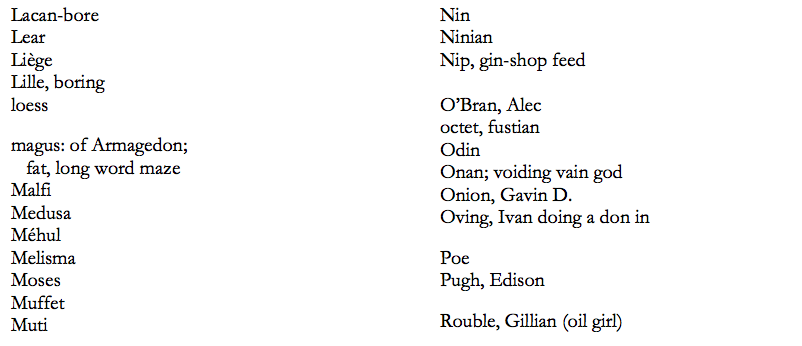

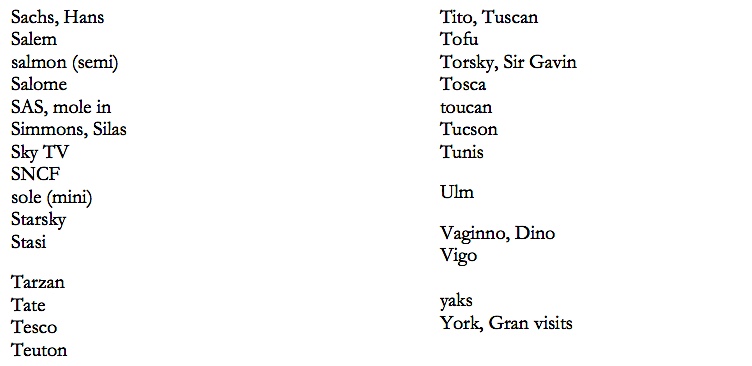

While I’m here, the absence of an index is most regrettable (see The joys of indexing). I hereby provide a sample, should my services be required for a future edition (cf. my draft index for Nicolas Robertson’s magnificent anagram tales, and even that for unlikely place-names to find in a blog dominated by Daoist ritual):

*** Bridge made another pleasurable pastime for musos on tour, playing on the back of a bus, and at airports—again suitably lubricated by alcohol. As Felix has learned to his cost when I partner him across the baize, my bidding skills are far inferior to his; month after month he patiently talks me through the fiendish opening bid of the multi 2 diamonds, knowing full well that I’m never going to get the hang of it (cf. A grand slam). You gather, of course, that my review of this book is informed by having played a minor role (again, allegedly, not always entirely sober) in many of the musical débacles that Felix evokes.

**** In my own early days depping for the BBC Symphony Orchestra, they would occasionally find they had booked too many extras, so they had to pay me not to play the violin—which, as my colleagues would agree, was most worthwhile (cf. “We are very lucky that your violin was broken”).

***** In a Coda from early 2018, Felix explains in apparently rational detail his support for Brexit—a choice that mystified most of his friends (cf. The C-word). Instead, here his readers might prefer a survey of changes since the 1960s to the hand-to-mouth existence of orchestral players (for whom Brexit is the latest disaster), and the gradual transition from the “knit your own yogurt” ethos of the early pioneers to a more polished “Chanel No.5” style—an account that he would be well placed to write.

The big-band arrangement would also suit a turbo-charged

The big-band arrangement would also suit a turbo-charged

The two-note motif could be any major third, actually: I doubt if anyone hears it as ti–so or la–fa, or even the fifth and third of a minor triad, as at the opening of

The two-note motif could be any major third, actually: I doubt if anyone hears it as ti–so or la–fa, or even the fifth and third of a minor triad, as at the opening of

Jesus in upbeat mood at crucifixion rehearsal.

Jesus in upbeat mood at crucifixion rehearsal.

In dhrupad renditions the nomtom syllables

In dhrupad renditions the nomtom syllables

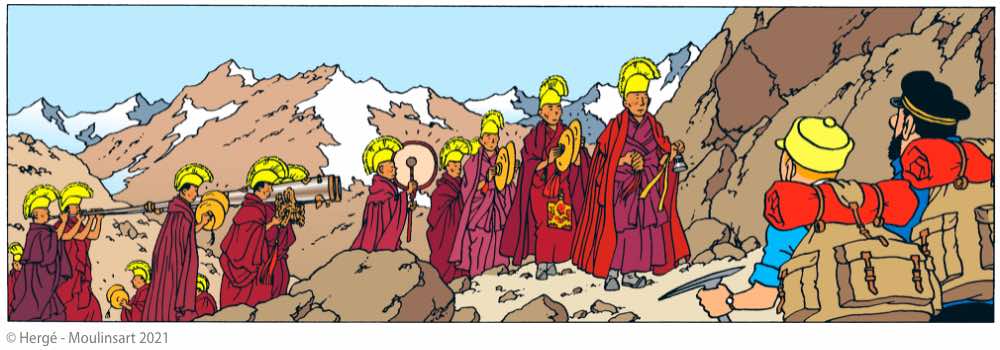

The character of Chang also features in

The character of Chang also features in

The roster of early American humorists commonly begins with

The roster of early American humorists commonly begins with