Among the controversial, countercultural icons who drove themselves to an early grave was Lenny Bruce (1925–66), “America’s No.1 Vomic”.

With my penchant for jazz biographies, in a similar vein [sic] is the extraordinary book

- Albert Goldman (from the journalism of Lawrence Schiller), Ladies and gentlemen, Lenny Bruce!! (1974). *

(Do read this most perceptive review by Wallace Markfield—interestingly garbled in the course of digitisation.)

The opening chapter, “A day in the life”, is a dazzling, graphic, blow-by-blow reconstruction of his arrival in New York in 1960 for a gig at the Blue Angel. Just a taster:

Around ten, a yellow cab, somewhat unsteadily driven, pulls up before a narrow gray dilapidated building on one of the crummiest sidestreets off the Square. Above the spattered pavement an extinguished neon sign flaps patches of cold hard shadow across the stone steps: HOTEL AMERICA, FREE PARKING. The cab opens with a jolt, back doors flying open so that two bare-headed men dressed in identical black raincoats can begin to crawl out from the debris within. […]

The night before, they wound up a very successful three-week run in Chicago at the Cloisters with a visit to the home of a certain hip show-biz druggist—a house so closely associated with drugs that show people call it the “shooting gallery”. Terry smoked a couple of joints, dropped two blue tabs of mescaline and skin-popped some Dilaudid; at the airport bar he also downed a couple of double Scotches. Lenny did his usual number: twelve 1/16th-grain Dilaudid pills counted out of a big brown bottle like saccharins, dissolved in a 1-cc. ampule of Methedrine, heated in a blackened old spoon over a shoe-struck lucifer and the resulting soup ingested from the leffel into a disposable needle and then whammed into the mainline until you feel like you’re living inside an igloo. […]

The America is one of the most bizarre hotels in the world: a combination whorehouse, opium den and lunatic asylum.

As Lenny honed his act at strip clubs, Goldman explores his background in

the fast-talking, pot-smoking, shtick-trading hipsters and hustlers who lent him his idiom, his rhythm, his taste in humor and his typically cynical and jaundiced view of society.

He describes Lenny’s connection with comics like Joe Ancis, Mort Sahl, and George Carlin. Joe

insisted on schlepping Kenny and Lenny to the Metropolitan and the Museum of Modern Art, taking them on whirlwind tours of both collections with his rapidly wagging tongue doing service as a catalog, guidebook and art-history course. “The fuckin’ Monet, schlepped out, half dead, in his last period, you dig? Painting water lilies—is that ridiculous! Water lilies, man, giant genius paintings, man, like the cat is ready to pack it in, but he has to blow one last out-chorus!

The book’s gory details of drug-taking and its paraphernalia, a staple of jazz biographies (Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Chet Baker (here and here), John Coltrane, and so on), are unsurpassed, and as Markfield observes “could easily serve as basic text in a graduate seminar on mainlining”.

Much as I love Chet’s ballads, he seems to have traded on his early angelic, melancholy image merely as a means to the end of a constant supply of drugs; whereas for Lenny the drugs and the performance went hand in hand, evoking the explorations and discipline of Billie and Miles. Amidst all the squalor, the book evokes the technique of Lenny’s creativity, the way he played the room (cf. Stewart Lee’s labyrinthine footnotes):

Suddenly, he lowers his head and shoots a bold glance into the house—a real arched-brow zinger. “Looks like some faggot decorator went nuts here with a staple gun!” Bam! He’s in, they’re tittering. Then he goes for the extension: “Whoo-who!” (high fag scream) “It’s just got to flow like this!” (big wrist flap and faggy, camp gestures as he dances around triggering off staples with his thumb). They’re starting to laugh. Now for a quick change-up. Take them into his confidence. “You know, when I was a kid, I always dreamed about going to a nightclub.” Nice, easy mood, nostalgia. Then into the thirties movie bits with the George Raft takes and the Eugene Pallette club-owner pushing back the panel in the office to get a view of the stage and the little shaded lamps on the tables and the tuxes and the deep-cleft gowns and the hair on the guys bayed back at the temples and Lenny home from the movies standing in front of the bathroom mirror with a scissors cutting away the hair from his temples so he’d have a hairline like Brian Aherne or Robert Taylor and then his disillusionment years later when he went to the Copa for the first time and everything was so tacky and there wasn’t even a men’s room attendant and they had whisky bottles right on the table like a Bay Parkway Jewish wedding and … and … and … By the balls! They’re hanging on his words. Eating out of his hand! Kvelling because it’s their experience—but exactly!

Indeed, not just Lenny’s lifestyle but the techniques of his free-flowing stage routine have aptly been likened to bebop:

He fancied himself an oral jazzman. His ideal was to walk out there like Charlie Parker, take that mike in his hand like a horn and blow, blow, blow everything that came into his head just as it came into his head with nothing censored, nothing translated, nothing mediated, until he was pure mind, pure head sending out brainwaves like radio waves into the heads of every man and woman seated in that vast hall. Sending, sending, sending, he would finally reach a point of clairvoyance where he was no longer a performer but rather a medium transmitting messages that just came to him from out there—from recall, fantasy, prophecy.

A point at which, like the practitioners of automatic writing, his tongue would outrun his mind and he would be saying things he didn’t plan to say, things that surprised, delighted him, cracked him up—as if he were a spectator at his own performance!

In another passage, Goldman comments:

The ghetto idiom was far more than a badge of hipness to Lenny Bruce: it was a paradigm of his art. For what the language of the slums teaches a born talker is, first, the power of extreme linguistic compression, and, second, the knack of reducing things to their vital essences in thought and image.

Jazz slang is pure abstraction. It consists of tight, monosyllabic that suggest cons in the “big house” mumbling surreptitiously out of the corners of their mouths. Words like “dig”, “groove” and “hip” are atomic compactions of meaning. They’re as hard and tight and tamped down as any idiom this side of the Rosetta Stone. `if any new expression comes along that can’t be compressed into such a brief little bark, jazz slang starts digesting it, shearing off a word here, a syllable there, until the original phrase has been cut down to a ghetto short.

The same impatient process of short-circuiting the obvious and capping on the conventional was obvious in jazz itself. […] Listening to Be-Bop, you’d be hard put to say whether it was the most laconic or the most prolix of jazz styles. At the very same that it was brooming out of jazz all the old clichés, it was floridly embellishing the new language with breathtaking runs and ornaments and arabesques. Hipster language was equally florid at times, delighting in far-fetched conceits and taxing circumlocution. A man over forty, for example, was said to be “on the Jersey side of the snatch play”.

But whereas for jazzers music made a pure, abstract language transcending their mundane lifestyle, Lenny’s act was inevitably entangled with it. He was getting busted for his act as well as his medicinal habits, becoming ensnared in a series of obscenity trials. But he was at his very best for the midnight gig at Carnegie Hall on 3rd February 1961, again brilliantly evoked by Goldman—riffing on topics such as moral philosophy, patriotism, the flag, homosexuality, Jewishness, humour, Communism, Kennedy, Eisenhower, drugs, venereal disease, the Ku Klux Klan, the Internal Revenue Service, and Shelly Berman. Had he lived on, an invitation to today’s White House seems unlikely. Goldman reflects:

What else is this whole jazz trip? You take your seat inside the cat’s head, like you’re stepping into one of those little cars in a funhouse. Then, pulled by some dark chain that you can’t shut off, you plunge into the darkness, down the inclines, up the slopes, around the sharp bends and into the dead ends; past bizarre, grotesque window displays and gooney, lurid frights and spectacles and whistles and sirens and scares—and even a long dark moody tunnel of love. It’s all a trip—and the best of it is that you don’t have the faintest idea where you’re going!

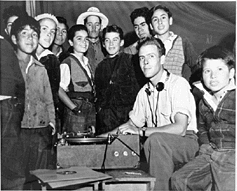

Here’s one of several video clips of his live act (more here, as well as many audio recordings online):

London

Chapter 10, “Persecution” describes Lenny’s 1962 sojourn at Peter Cook’s new London club The Establishment—designed to elude the censoring scissors of the Lord Chamberlain’s office, “maiming English stage plays since the 16th century”. Indeed, this was part of an exchange of hostages that led to the Beyond the Fringe team’s long run on Broadway—International Cultural Exchange, YAY!

Lenny in London! Sounds bizarre, doesn’t it? Like James Brown at the Bolshoi. Or Little Richard at La Scala.

(Nice idea, but not so bizarre—neither London, Moscow, nor Milan are so culturally monochrome…)

Here’s an intriguing prequel to the misguided vinegar advertisement, and indeed Always look on the bright side of life:

The Establishment was preparing a skit that depicted Christ Jesus as an upper-class gent hung between two cockney-talking thieves, who complain in their petty, rancorous way: “ ’E’s getting all the vinegar sponges!”

Goldman goes on:

Lenny’s notions of England—compounded from old Hollywood flicks and Alec Guinness imports—were queer, to say the least. As Jonathan Miller summed them up, Lenny saw Great Britain as “a country set in the heart of India bossed by a Queen who wore a ball dress. The population had bad teeth, wore drab clothes and went in for furtive and bizarre murders”.

Not all of this was so wide of the mark.

As Lenny’s apostle Kenneth Tynan observed,

If Beyond the fringe was a pinprick, Mr Bruce was a bloodbath.

As ever, critical responses were polarized. Brian Glanville later wrote in The Spectator:

Bruce has taken humour farther, and deeper, than any of the new wave of American comedians. […] Indeed, the very essence of the new wave is that one hears an individual voice talking, giving vent to its own perception and, in Bruce’s case, its own obsessions. An act such as this requires a good deal more than exhibitionism; it also need courage and passion. Essentially, it is not “sick” humour at all. The word is a tiresome irrelevance—but super-ego humour: a brave voice calling from the nursery.

He was denied entry the following year as an “undesirable alien”.

I’d be curious to learn what Alan Bennett thought of Lenny, but his influence on Dud ‘n’ Pete can be heard in their later foul-mouthed Derek and Clive recordings. Christopher Hitchens wrote a fine article on these transatlantic comedy genealogies.

Goldman devotes a perceptive chapter to “The greatest trial on earth”, a high-profile obcenity case over six months in Manhattan in 1964. Despite support from an array of prominent literati, Lenny was sentenced; freed on bail pending an appeal, as his mental and physical health went into a tailspin, exacerbated by paranoia over litigation, he died in squalor.

The only flaw I find with Goldman’s brilliant book is that it lacks an index. See also Doubletalk.

* * *

All this is a far cry from the bland hagiography of Chinese biographies. And the book reminds me again that the post-war era before the Swinging Sixties wasn’t entirely drab and conformist (see e.g. Paul Bowles, Gary Snyder). It also highlights issues of free speech, which are so urgent today. By comparison with Lenny, the challenging routines of Richard Pryor, or Stewart Lee, seem almost genteel. Still, the latter’s travails over Jerry Springer: the opera, detailed in How I escaped my certain fate, and his ripostes in “Stand-up comedian” (2005) and ” ’90s comedian” (2006), richly deserve attention; while Lee too highlights his debt to free jazz, his art is acutely disciplined (for his thoughts on Lenny, see here).

* The title’s punctuation reminds me of Mahler’s fondness for exclamation marks!!!

The list of countries also evokes the Olympic medals table—with USA, China, and even the UK ranking high, pursued by France, Germany, Australia, Japan, and so on. Further down, Romania, Thailand, and Brazil put in plucky performances. I like some of the fortuitous juxtapositions that it produces daily (left).

The list of countries also evokes the Olympic medals table—with USA, China, and even the UK ranking high, pursued by France, Germany, Australia, Japan, and so on. Further down, Romania, Thailand, and Brazil put in plucky performances. I like some of the fortuitous juxtapositions that it produces daily (left).

Hannibal has further supplemented my list of illustrious Chinese stammerers with a biographical sketch of the muralist Dong Yu 董羽. As described in Song[/sheng]chao minghua ping 宋[/聖]朝名畫評 by the Song-dynasty author Liu Daochun 劉道醇, Dong Yu was an attendant to

Hannibal has further supplemented my list of illustrious Chinese stammerers with a biographical sketch of the muralist Dong Yu 董羽. As described in Song[/sheng]chao minghua ping 宋[/聖]朝名畫評 by the Song-dynasty author Liu Daochun 劉道醇, Dong Yu was an attendant to